20 April 2014

If Not His, Whose ?

— George Koppelman & Daniel Wechsler. Shakespeare’s Beehive. An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light. With folding plate of the Trailing Blank opposite p. 220. Printed in red and black throughout. xii, 339, [1] pp. Axletree Books, 2014.

It is, after all, what we do, those of us who look at books and bits of paper or cloth : we attempt to understand the significance of what is in front of us. Sometimes it is “ easy ” (never simple), but in fact no one had ever noticed or bothered to look. There are clues (concrete or contextual), but the essence is to look and to think.

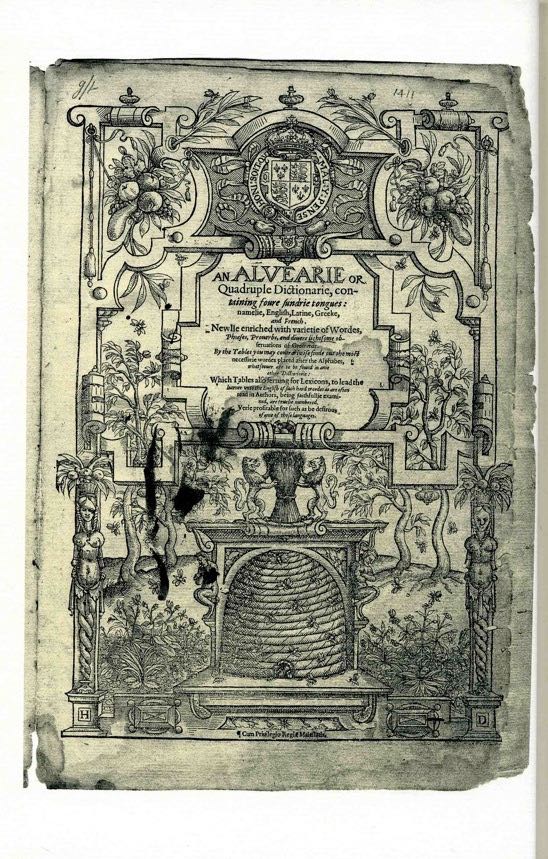

Shakespeare’s Beehive is the story of an annotated copy of An Alvearie or Quadruple Dictionary . . . by John Baret, a large folio volume published by Henry Denham in 1580 and never reprinted or even digitized until now. The copy in question bears signs of a nineteenth century owner, Lady Georgiana Fullerton, and in the twenty-first century it was dislodged by the “ great flood, ” the internet auction, “ which causes material to rise to the surface that had previously been hidden ”. George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler, two New York antiquarian booksellers, bought the book five years ago and began weighing the evidence, apparent to them from the outset, that this was William Shakespeare’s own richly annotated word-hoard.

It is the stuff of history that no manuscripts of Shakespeare’s plays are known to have survived, and that the few signatures known to be genuine display considerable variation. The first part of Shakespeare’s Beehive rehearses many of the possible objections to this identification of Shakespeare as the annotator in a review of the background necessary to evaluate the Alvearie . There are brief and well documented chapters on old books and their survival, early modern dictionaries (and those known to be relevant to Shakespeare’s vocabulary, such as the Baret), the life of William Shakespeare (including the theory that he worked for a time as a proof reader in the printing house of Henry Denham), the meager but necessary clues to be gleaned from paleography. The scarcity of surviving annotated dictionaries from this period is addressed. And then the fun begins, as Koppelman and Wechsler consider what Shakespeare’s works have to say about handwriting, and what is known of his reading (including Biblical passages and their sources). The Beehive is illustrated throughout with examples from the original. Koppelman and Wechsler have coined a beautiful and useful term, mute annotations, to refer to underlinings, slashes, and other small marks, as distinct from added words. They employ the term spoken annotations for written additions to the text “ that youth and observation copied there. ”

This passage by T.W. Baldwin on John Baret’s Alvearie (from a book published in 1944) is given as one of the book’s epigrams :

Baret was in effect the standard English dictionary of Shakespeare’s schooldays, and must have had powerful influence in shaping the English definitions of Shakespeare’s generation. But it is not likely that Shakespeare would have preserved the patterns so accurately if he had not himself turned many a time and oft to Baret for his varied synonyms.

The true significance of these sentences is found in the second part of Shakespeare’s Beehive, a close reading of the annotations to Baret and their appearance in the plays and poems. This is a work of wide-ranging erudition (beyond your correspondent’s capacity to evaluate save as a reader interested in language and the process of composition, and to note the thorough documentation of the arguments presented). The evidence that Koppelman and Wechsler adduce is linguistic and specific to this annotated copy of the Alvearie ; the vocabulary of Shakespeare’s writings is known and well summarized. Mention must be made of Patricia Parker’s Shakespeare from the Margins (1996), and the echoes of Baret’s preface to the letter E that she discerned in Hamlet (anchored by underlinings and word choices in this copy). The chapters of part two examine successively Hamlet, the narrative poems, the Sonnets, the early Comedies, the early Histories, the character of Falstaff, and the source of names in Shakespeare. Koppelman and Wechsler devote a penultimate chapter to “ My dearling Ps. 22 ”, which they deem “ the most interesting and important spoken annotation in the entire text portion of our Alvearie. ” The annotation refers to a usage in the Great Bible (1540) or Bishops’ Bible (1568) and creates a chain linking incidents in Shakespeare’s upbringing, Othello, the Sonnets, Coriolanus and his mother Volumnia, the North translation of Plutarch’s Lives, and the death of Shakespeare’s mother in 1608.

The ordinariness of the individual annotations is, to me, precisely what argues for their authenticity : they form not a rough draft of any single text, but a tool kit. The connections between Baret’s word store and the plays and poems all point to the transformation that occurs in the space between an author’s notes and composition : the play of language. Koppelman and Wechsler quote Stanley Wells on the Elizabethan vocabulary, in a period of expansion. “ This process involved much coining of new words, often on the basis of, especially, Latin and French, and encouraged the use of old words in new forms, senses, and combinations. Shakespeare was an indefatigable innovator. ” Again and again, there are examples of word choices, combinations, and inversions, each one unique in Shakespeare’s writings, traced to specific pages and passages in this copy of Baret. “ What’s curious is how often these have but a single usage in Shakespeare — a pattern that is in total keeping with Shakeseare’s frequent demonstration of reaching for a certain verbal choice one time and one time only. ” One also comes to understand how flat and dull modern standardized spelling have made our pages.

Baret’s definition of W.44 / ¶ Wanne. Vide Pale. (with that red slash indicating a mute annotation) shows up in the Comedy of Errors, “ Aye me poore man, how pale and wan he looks. ” (Note the inversion rather than strict copying of word order.) Koppelman and Wechsler write, “ The annotator is obsessed with saying it both ways, and Shakespeare does too, time and time again. ” These annotations seem unlikely to be the result of reverse engineering. The pattern is too reticular, the tissue resiliently interwoven yet diaphanous.

Page 220 is a transcription of the text of the Trailing Blank, heavily annotated with strings of words in English, French, and Latin — dubbed a word salad by the authors — that are to be found in Henry IV, Merry Wives of Windsor, and Henry V. This serves to narrowly define the time period of the annotations. This is a brilliant page, in which form and function reveal themselves as inseparable ; a facsimile of the annotated page is present here as a folding plate. This is a high point of the excellent design of the book (by Jerry Kelly of New York). That there is no index is a conscious design choice, and a command : read the book.

Shakespeare’s ‘ Vagina ’

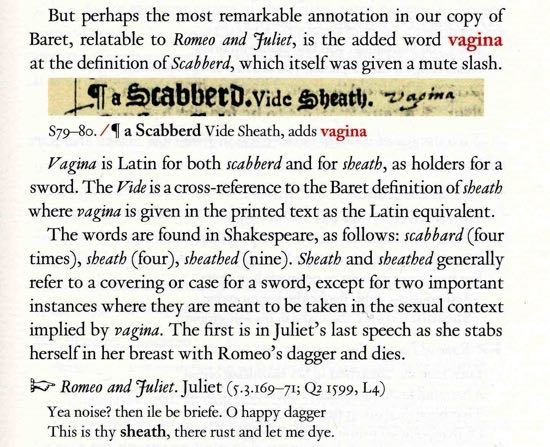

“ But perhaps the most remarkable annotation in our copy of Baret, relatable to Romeo and Juliet, is the added word vagina at the definition of Scabberd, which itself was given a mute slash. ”

Koppelman and Wechsler discuss the occurrence of scabberd and sheath or sheathed in Shakespeare. Juliet’s last speech, “ . . . O happy dagger / This is thy sheath, there rust and let me dye ” is specifically linked by A.D. Nuttall to the common anatomical meaning, “ Her language is sexual. ” While the OED records the first usage of vagina as an anatomical word in English only in 1682, Lewis and Short trace the anatomical meaning to Plautus. T.W. Baldwin and other scholars offer clear evidence that Plautus formed part of the Elizabethan curriculum ; Koppelman and Wechsler cite a line in Pseudolus that translates “ Not fitting into thy sheath soldier ? ”

Sir Thomas Browne wrote “ What song the Syrens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, though puzzling questions, are not beyond all conjecture. ” Koppelman and Wechsler give the briefest of notes on the nineteenth century provenance of the book. Lady Georgiana Fullerton was a novelist and philanthropist, and a granddaughter of the fifth duke of Devonshire. “ All the dukes of Devonshire were men of letters and collectors of books ”, writes W.Y. Fletcher in English Book Collectors (1902). The Cavendish family were wealthy and prominent since Tudor times despite exile and debt. It is entirely plausible that this copy of the Alvearie once formed part of a large library — how better for a book to survive than among ten thousand others ? — and once it might even have been known to be Shakespeare’s own copy, until that knowledge was lost or the book was moved from one shelf to another. It may never be possible to trace the full history of the ownership of the Alvearie ; but the linguistic evidence is strong enough to convince all but the most wilful and perverse doubters.

Koppelman and Wechsler mention the sensation of entering a Borgesian labyrinth with the discovery of the Alvearie ; and supreme of all imaginary delights would be to show Shakespeare’s dictionary to Borges, to Avram Davidson, or to Virginia Woolf (I am thinking of her reflections on Shakespeare’s sister in A Room of One’s Own) — and to learn their responses to this profoundly intertextual artefact.

One of the authors is well known to your correspondent (for a decade or more) ; I have not seen the Alvearie. I had an advance copy of Shakespeare’s Beehive with time to read and think about its arguments, which I have come to accept not by reason of friendship but because of the hard evidence. I will be reading and re-reading lots of Shakespeare this year, and, with greatest pleasure in the task, doing what I usually do : watch the dance of language upon the page.

— — — —

Who hath suche bees as your maister in hys head.

— Nicholas Udall, Ralph Roister Doister (1553)

Shakespeare’s Beehive sticks close to the linguistic evidence and the use of words. This book will alter many certainties : there will be nay-sayers and skeptics who will accept no possible proof. In the OED, I find a citation for “ nest of hornets ” with a figurative meaning traced to 1593 ; the usage “ to provoke a nest of waspes ” is traced to 1642. It will be fun to observe the debate unfold. [HWW]

— — — —

The Best Book of the Year 2014

It is only April and your correspondent has read a couple of notable books : a tricky science fiction tale, Strange Bodies by Marcel Theroux (discussed last month) ; and a blistering satire, UnAmerica by Momus (forthcoming from Penny-Ante Editions). Other commendable books will be published and read with pleasure and interest during the coming months.

But readers, there can be no doubt : on grounds of original content and beautiful design, and for launching ideas that will resonate where ever English is remembered, Shakespeare’s Beehive is the Best Book of the Year 2014.

The Best Book of the Year.

— — — —

Copyright © 2014

Temporary Culture and individual contributors.

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.