The Darkening Garden. A Short Lexicon of Horror by John Clute.

Cauheegan; Seattle: Payseur & Schmidt, [2006].

Illustrated. [xii], 162, [4] pp. $45.00

reviewed by Henry Wessells

[First published in The New York Review of Science Fiction 19:7, no. 223 (March 2007). All rights reserved.]

The Darkening Garden is a brilliant, irritating book, a dark little jewel of a grenade tossed into the cocktail party of genre criticism. Its subtitle, A Short Lexicon of Horror, is Clutean misdirection deftly understated. What we have here is a philosophical engine, an encyclopedia in miniature (assuming a certain degree of knowledge on the reader, author entries can be found elsewhere or simply imagined) and, most importantly, a record of how John Clute thinks. This last is no small matter.

The Darkening Garden is a collection of thirty short essays on topics relevant to the horror sort of fantastic literature. No particular affinity for horror literature is required. The terms that Clute defines will be of interest to all readers, just as the critical approach these terms articulate bears upon all sorts of fantastic literature. (I use the neutral term sort — less charged than flavor or variety — here, precisely, in place of genre or mode because definition of genre is one of the concerns of the book at hand.)

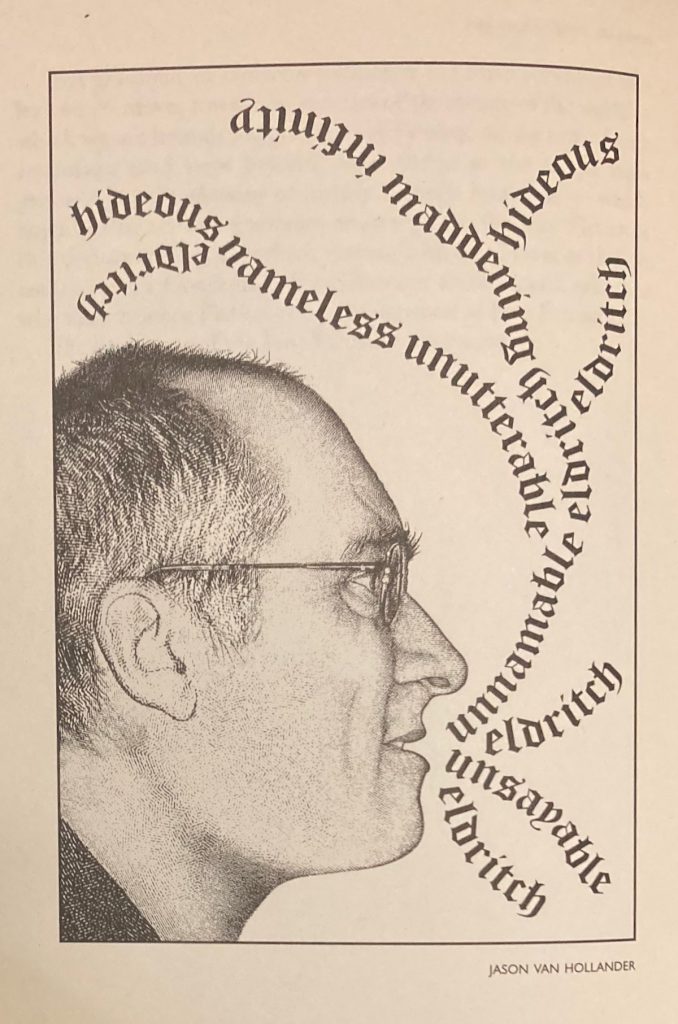

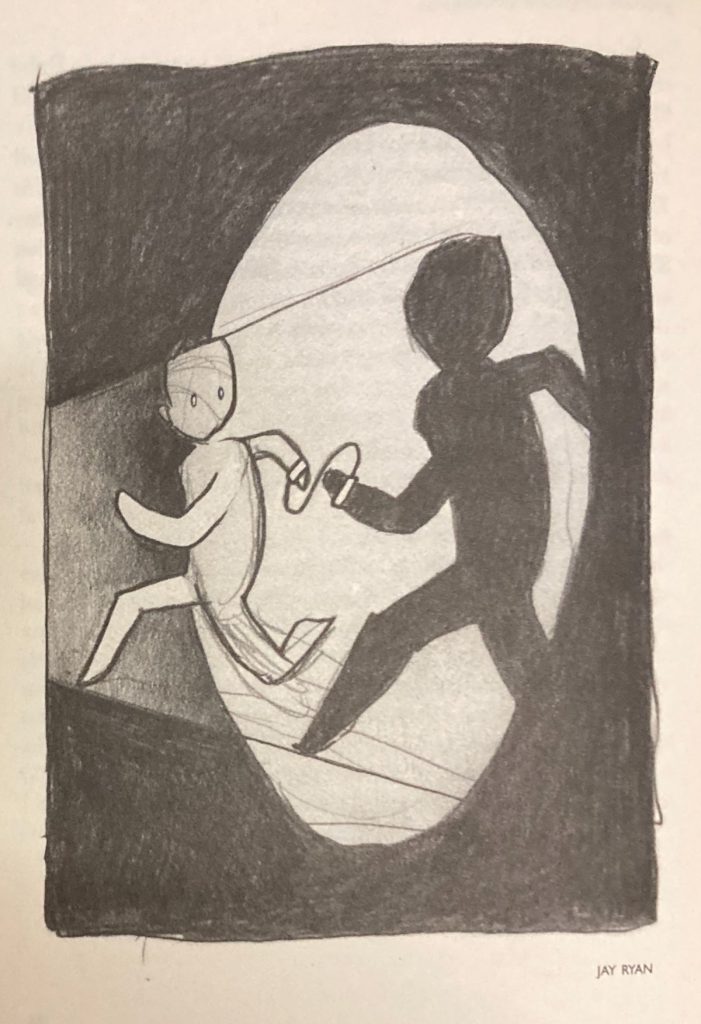

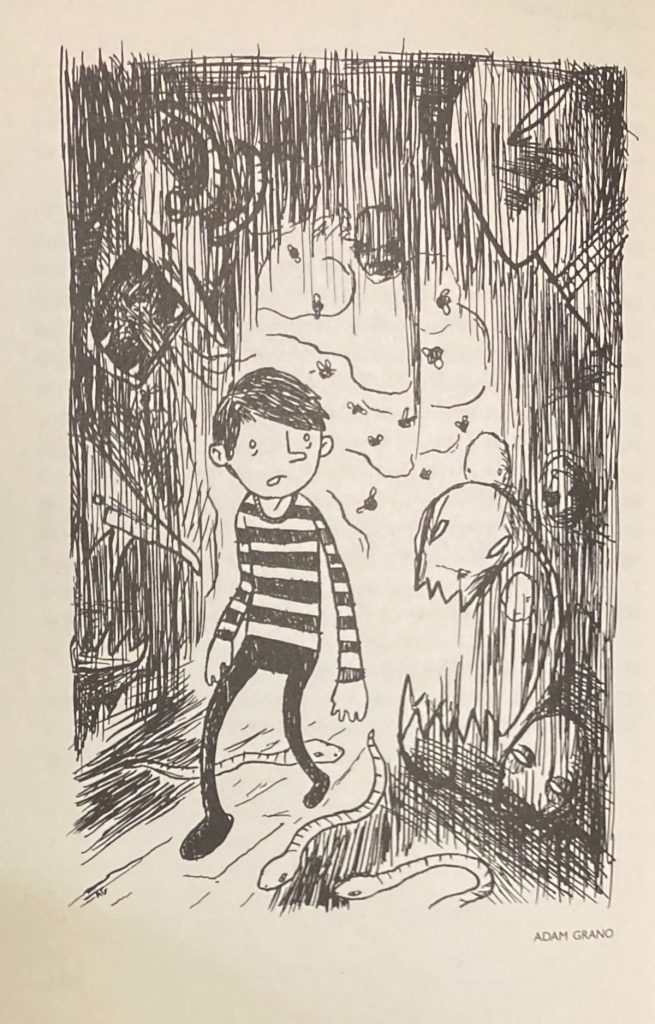

The physical form of this little book warrants a few words. It’s a handsome thing, and if it is bound in black cloth not unlike the old Arkham House titles, the decorative stamping and the wraparound band are evidence of a different sensibility. The two books published by Payseur & Schmidt that I have seen have high production values and a stylish look. This is in sharp contrast with the utilitarian, even ugly, form of books from the first wave of small press science fiction publishing in the Pacific northwest that began two decades ago. I suppose one might look to Ron Drummond’s Incunabula Press as an early milepost on the path of design. The typography of this book is clean and makes use of small capitals in two fonts to indicate types of cross references (actual and putative); in citing from the book I have only used initial capitals for named terms. Each of the essays in The Darkening Garden is illustrated with a full-page black and white image commissioned from a different (living) artist. The conversation is thus already underway when the reader begins.

The essays, typically two to three or more pages in length, describe “an argument about the nature of Horror” and in his preface, Clute prescribes one possible sequence in which this argument is developed. It is not necessary to follow that prescription. The theory is coherent and any part is connected with the central concern. As Charles Fort wrote, when measuring a circle, begin anywhere.

Of these contrarian modes, Horror is the extremest: Science Fiction, which might be called the Fantastic of the Case, declares that certain fixes answer the world, as though the world were composed of query (it is the least angry of genres); Fantasy (see Free Fantastic) repudiates the Wrongness of the world, and makes its escape from prison into a truer world (its rage may sublimate heavenwards, or not); but Horror (see Bound Fantastic) comprises a process of uncovering the true nature of the prison, which is seen to be inescapable, for the prison of the world is where the buck stops, huis clos. Horror exercises its rage ripping open the one-way gates to truth; after which is silence, a deep transparency of utter rage (88).

Central to this definition of horror — “the naked, impersonal malice of the world” — is what can only be seen as a complete reassessment of the import of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”. The entry (by Mike Ashley) in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997) notes, “Native Magic plays a minor role in the story, yet becomes a convenient route to making this a Rationalized Fantasy rather than a confrontation with Reality” (224). In The Darkening Garden, Clute writes, “By the time Kurtz cries out at last, ‘The horror, the horror!’, he has transited all that fiddle of story, and can only utter the final grammar of reality entire, a rage isomorphic with how the world is truly said, the still point where any great Horror story ends: nothing but true, intransitive. Horror is that category of stories set in worlds that are false until the tale is told” (89).

Key entries in the lexicon discuss the Bound Fantastic and Free Fantastic cited above, and such terms as Difficulty (noting “the long survival of apparent estrangement devices”), Attempted Rescue, Fustian, Revel, Thickening, and Vastation. This is a vocabulary that Clute has been employing systematically in recent writings; now that the lexicon is placed before the world, the risky business of (re)defining terms to suit a private need is complete, and the private concern made universal language. Clute outlines a four-part dynamic model of Horror that is a dark inverse of the model proposed in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy: SIGHTING, THICKENING, REVEL, AFTERMATH. Thickening, a cumulative process, is the somber reflection of Thinning in fantasy, and moves the story toward the Revel, “when the truth of things glares through” (117). “Vastation occurs when the ‘malignant system of the world’ (as Le Fanu puts it) is tearing you apart” (119).

In the entry for Free Fantastic Clute defines a starting point for the literatures of the fantastic: “since its first parturition (of many) after around 1750” (71). This is not a static definition, since it implies multiple renewals, but it is clear that Clute (in the company of many others) sees the mid-eighteenth-century emergence of fantastical literature as a Double of the Enlightenment and the economic and political exploitation launching itself upon the world. (Wendy Walker’s ongoing study of the close ties between slave ownership and the Gothic is relevant here; Clute cites A Specter Is Haunting Europe: a Sociohistorical Approach to the Fantastic, a 1990 work by Jose B. Monleon.) Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, A Story, translated by William Marshall, Gent. (1764) and Mercier’s L’An 2440, rêve s’il en fût jamais (1771; translated as Memoirs of the Year Two Thousand Five Hundred, 1772) are gateposts of this emerging path of literature.

The entry for Picture Books is intriguing and provocative: “In this understanding, picture books can be seen as a kind of ideogram of the full meaning of the term Bound Fantastic. [. . .] Many examples have never been brought into prominence; others have never been understood in terms of horrific doubleness of intent” (112). The work of Maurice Sendak is particularly noted, with some stunning insights.

Robert Sheckley wrote, “‘Don’t pick at the metaphor,’ Thoth-Hermes advised him, ‘it leaves a nasty scab.’” There are a couple of places in Clute’s book where I must. I understand what he is trying to get at in he entry on Cloaca, for he writes, “what is defined as Portal in Fantasy does not exist in horror: so the term Cloaca is applied here to semblances of Portals when such are uncovered [. . .] lesions in the Thickening of the world towards the moment of truth, when the rind of things is peeled” (38). This is one term that fails to impress. Perhaps this is because when I first picked up The Darkening Garden, I was reading The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson, an account of the epidemiology of the 1854 cholera epidemic in London and a reflection on cities, disease, and sewers: “the most advanced and elaborate sewage system in the entire world was operational by 1865 [. . .] It remains the backbone of London‘s waste-management system to this day. Tourists may marvel at Big Ben or the London Tower, but beneath their feet lies the most impressive engineering wonder of all.” What Clute describes is a blocked sewer, a failed system; the horror lies in the fact that it is a dead end. I also suspect he is not unaware of the imperfections of the term, for he writes,“The Cloaca is a Parody of the Portal: an extremely bad joke (such being common in tales of Horror) about the true nature of the world” and then goes on to indulge in one of his own.

I also think it is a bit much to say in the midst of an otherwise lucid discussion of the origins of the three genres, “nor (in any case) did history exist until Gibbon conceived of Empires toppling (rather than Emperors) into the grave” (34). Western Europe may not have known, then, of Ibn Khaldun or older Indian concepts of the cyclical destructions of the (multiple) universes, but it is a stretch to credit Gibbon with such inventive power, particularly in view of the oriental subject matter of so many Gothic works, and the migration of Indian tales into medieval European literature.

Those of us who might wish for a minim of Johnsonian directness (a single direct statement like a whack to the head) — whether as starting point or as conclusion — really should know better by now. Clute is the master of periphrasis and the circling, reiterated metaphor, employing pyrotechnic diction to summon insights that are at once calculated and spontaneous. Also, I think one should be wary of reading anything at all into the apparent omissions — despite the frequent literary examples given (some tantamount to rediscovery of a neglected author), The Darkening Garden is a work written in shorthand. In the main entry on Horror, only Joseph Conrad is named directly; Stalin appears in an aside; Nabokov and J. M. Barrie are implicated through their creations. The entry for Free Fantastic names no individual author; while several others include citations of specific works or author lists. Attempted Rescue includes a nice paradox from Peter Straub:

If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you; if you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you (30).

The Darkening Garden is an exuberantly bleak book, in the same way that its author is, in conversation, one of the most genially pessimistic people I've ever met. His quick smile and energetic gaze are part of the gleeful frankness with which he will discuss the utterly unsustainable foundations of contemporary American life as evidenced by the vast size of houses or the number of miles people drive to fill implacable desires — what Peter Whybrow calls the “mismatch between the wealth of good and the technology-rich environment that we have created, and the biological limits of who we are as evolved creatures of our planet”. The vision of looming catastrophe is rooted in unflinching observation of the world, as well as of literature. In Vastation, Clute illustrates this line of thought with a well chosen verse extract (143-4):

But if the contemporary Horror novel is genuinely transgressive, it is not so through any discovery of new fluxes of affect. It is transgressive because it continues to tell us that Baron Frankenstein is the true monster, that we who are the owners of the world are the devourers of the world.

Were we wrong to have eaten

it all in just one century? No. we were

the true suicide bombers, and Paradise

was our reward. We will have left nothing behind

but the memory of our movie stars.

The passage quoted by Clute is from “Prayer of Thanksgiving” by Tom Disch.

What is clear from The Darkening Garden is that Clute has read and internalized a vast range of books and cites them with accuracy and precision. Rare qualities, “especially in a field like sf and fantasy criticism where vagueness is too readily accepted” (Kaveney). Other living readers might equal his eclecticism, but more importantly, after these diverse books are recorded as data, something else happens, and that spark of association is why, ultimately, one must view Clute’s reading and criticism as fundamentally creative in nature.

The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, indisputably a collaborative effort, was nonetheless thoroughly shaped by Clute’s lifelong creative examination of the literatures of the fantastic. It is possible to use it, fruitfully, as a desk reference of superior reliability; but it is far more likely that the imbedded agents — Clute’s ideas and terminology — will prompt new thinking about texts one knows or empower the reader to discover new stories. In the years since its publication it has become clear that The Encyclopedia of Fantasy was not an end in itself, but one stage in an evolving critical vocabulary. It was the opening of the doors to the labyrinth (perhaps that should be LABYRINTH, a nod to the incantatory power of the cross-reference; only, perhaps not).

From the word labyrinth I would like to step to the ancient Celtic symbol, the triskelion. On the Isle of Man it takes the form of three conjoined legs, an endlessly bounding wheel; in Brittany, where its shape is more stylized, the three branches open to spirals (or labyrinths). To someone inside any one of the spirals — call them the three genres, fantasy, science fiction, and horror — the limits of genre would appear to be defined by that labyrinth; but at the center, where all three labyrinths join, one can see that all three form parts of a unity. It seems to me that Clute has been working towards a unified critical approach to the three genres. That the ostensible subject of The Darkening Garden is horror is entirely appropriate: in Sicily, the triskelion takes the form of three legs with gorgon’s head at the central junction.

I mentioned Sheckley before. In a 1982 short story “The Eye of Reality”, he wrote, “Looking into the stone, a man may see all that is or was or may be. [. . .] ‘Understanding is sensuous,’ said the third man, an artist. [. . .] ‘Like you,’ he said, ‘I saw pretty much what I always see.’”

In a recent review of a book by Will Self, and ostensibly talking about the London of Self’s novel, Clute wrote, “the mental map of London called the Knowledge, which all legal cabbies must master — is as chthonic and veined, as rudimentary and as unendingly fractal, as the London of Iain Sinclair or Peter Ackroyd . . . a seethe, a map, a magpie maestoso maggotty splurge of hatred and love and stuff . . . less an actual map than a ratking grammar of route instructions, memorization of which allows one to go from anywhere to anywhere within the vast maze of London” (Excessive Candour, SciFi Weekly 506, [2007]). A nice crunchy linkage of phrases, there, and no doubt an accurate metaphorical assessment of the London of The Book of Dave. But it is also a description of Clute’s preoccupations and the nature of his critical thinking, not metaphor but plain seething fact.

For if The Darkening Garden is anything, it is the “ratking grammar of route instructions” to the critical labyrinth whose patterns Clute has been tracing for more than a decade — perhaps his entire life. In the introduction to The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, Clute alludes to the shape of a “map of fantasy” (vii) and the notion of mapping texts pervades the entire work; in the preface to The Darkening Garden, Clute acknowledges that Graham Sleight suggested to him the “useful distinction between architectural and move models”. For Clute, it seems, the working mode for the critical discussion of fantastical literature is no longer a geography but a choreography that defines, notates, and manifests the dancing energy of attention.

Works cited:

The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. Edited by John Clute and John Grant (St. Martin’s Press, 1997).

Johnson, Steven. The Ghost Map (Riverhead, 2006), p. 208.

Kaveney, Roz, in Polder. A Festschrift for John Clute and Judith Clute. Edited by Farah Mendlesohn (Old Earth Books, 2006), p. 270.

Sheckley, Robert. “Cordle to Onion to Carrot”, in Can You Feel Anything When I Do This? (Doubleday, 1971), p. 24.

— —. “The Eye of Reality”, in Is That What People Do? (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984), p. 3.

Whybrow, Peter C. American Mania. When More Is Not Enough (W. W. Norton, 2005), p. 107.

Henry Wessells lives and reads and reiterates metaphors in Montclair, New Jersey.

The cover of the issue of NYRSF featured Jason van Hollander’s FUSTIAN portrait of John Clute ; I have added a few other illustrations from the book : Bound Fantastic by Jay Ryan ; Thickening by Adam Grano ; and Revel by Tara McPherson. The complete text of The Darkening Garden is available in Clute’s Stay (Beccon, 2014).