Wharton Esherick, recognized as a key link between the pre-1916 Arts and Crafts Movement and the renewed interest in the crafts following the Second World War, is most widely known for his sculptures and non-traditional furniture designs from the late 1920s and 1930s onward. In his long and varied career, Esherick (1887-1970) joined the traditions of the decorative arts with those of the fine arts. He was also a noted printmaker and book illustrator whose work was published in popular magazines and in elegant limited editions and remains sought after by collectors to this day.

Curiously enough, Esherick’s woodcut work, produced almost entirely between 1922 and 1936, occurred in a period of great artistic transition for him, when he sought a medium in which he could evolve his own characteristic style. Formally trained in oil and watercolor painting, Esherick soon abandoned painting as he developed an identifiable style in his woodcuts. He also began to carve simple, woodcut-like designs on antique furniture, to experiment more freely and less academically with sculpture, and to design furniture to be ornamented with carvings. By the early 1930s, Esherick began receiving important design commissions and had a rising reputation. His Pennsylvania Hill House interior was exhibited at the New York World’s Fair in 1940, and major exhibitions of his furniture and sculpture followed during the next decades. Esherick’s studio, a building of his own design that evolved over a 40-year period, incorporates countless marks of its owner’s personality; a larger woodworking shop, constructed in 1956 from plans by architect Louis I. Kahn, bears many of Esherick’s distinctive design signatures.

Wharton Harris Esherick was born on July 15, 1887, in Philadelphia. He was one of seven children. His family resided on Locust Street, in an area now occupied by the University of Pennsylvania, and possessed independent means. From an early age, Esherick was interested in drawing, and soon determined to become an artist, despite the fact that his parents discouraged him. He attended the Manual Training High School where he took courses in woodworking and metalsmithing and graduated in 1906. Esherick studied painting at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts), and earned a scholarship to a two-year program at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He studied under William Merritt Chase, Thomas Anschutz and Cecilia Beaux, and produced technically proficient work, yet became disenchanted and left before completion of his studies.

Esherick worked briefly as an illustrator for Philadelphia newspapers and as then resident commercial artist for the Victor Talking Machine company. In 1912, when he lost his job, Esherick and his wife Letty moved out of the city to a farmhouse in Paoli, Pennsylvania, where he concentrated on painting. Yet before long, Esherick found himself dissatisfied with the work he produced using the academic approach to art of his formal training.

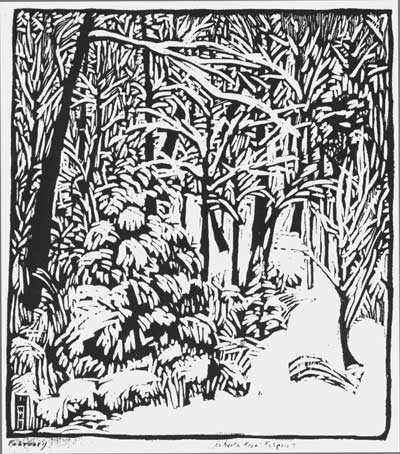

February by Wharton Esherick (from the collection of Henry Wessells)

View from Esherick’s studio window, February 1999. Photograph by Henry Wessells

In 1919, Esherick was invited to join the faculty of an experimental school for "organic learning" in Fairhope, Alabama. Located on Mobile Bay, Fairhope was then an artist colony that attracted many writers, painters and craftsmen during the winter. Esherick met Sherwood Anderson, who remained a life-long friend. Significantly, Esherick obtained his first set of woodcarving tools and began making decorative frames for his own paintings. He also met Mary Marcy, a young woman who was writing a children’s book on evolution. Esherick carved a woodcut illustration for one of her verses. She, in turn, was inspired by his illustration and they began a correspondence that resulted in Esherick carving more than 100 blocks.

Fairhope, Alabama

Back in Pennsylvania in 1920, he converted his barn into a studio, and began making woodcuts and carving small objects, including The Race, a game consisting of a set of six brightly colored figures on horseback.

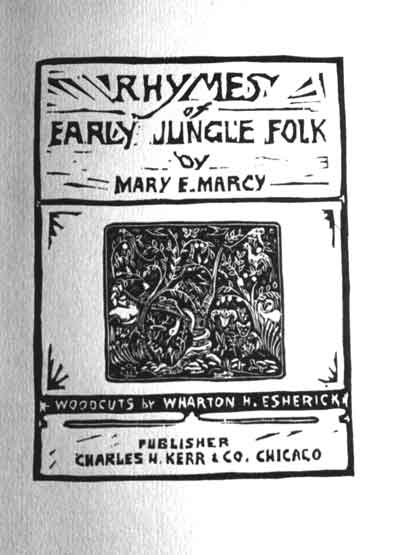

Esherick’s early woodcuts were carved on inexpensive flat grain boards. He made dramatic use of contrasts, primitive shapes, and the textures of the wood in the woodcuts for the first book he illustrated. This was Mary Marcy’s Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk, verses on the then still controversial subject of evolution, issued in 1922 by the socialist publishing house of Charles H. Kerr & Company of Chicago. The title page is an Esherick woodcut, and more than 70 of the 100 blocks carved by Esherick were selected to illustrate the book. Marcy died the month before the book appeared.

Esherick found himself intrigued by the possibilities of the new art form. He acquired a Washington hand press and began to produce his own prints in small editions (frequently between 20 and 60 prints). In 1922, Esherick printed a woodcut invitation to a showing of his paintings and woodcuts at his barn. Esherick’s woodcuts, and later wood engravings, also began appearing in national magazines, such as Century, Vanity Fair, and The Forum. In 1922-1923, Century published a series of woodcuts illustrating different months (January -- Blankets of Snow; February; March -- The Manure Spreader; April; September Corn; and December). At much the same time, Century published woodcuts by J.J. Lankes, a contemporary whose work is frequently associated with the writings of poet Robert Frost. The woodcuts of Lankes and Esherick have a certain resemblance, both in their execution and in the choice of subject matter.

A 1928 wood engraving, Of a Great City, is an image of Esherick’s friend Theodore Dreiser at work at an Art Deco desk, beneath a tall window that gives a glimpse of a teeming city. Dreiser worked on the stage adaptation of An American Tragedy while a guest in Esherick’s farmhouse.

During the early 1920s, Esherick had met Harold Mason, owner of the Centaur Book Shop in Philadelphia. Mason had a keen appreciation of the book arts, and sought to produce fine press books, printed on hand made papers in limited editions. Esherick

The Centaur Book Shop

made Morse a Centaur (1924), an ornament of iron and wood that adorned the shop sign for many years. He also made several other centaur figures during the late 1920s.

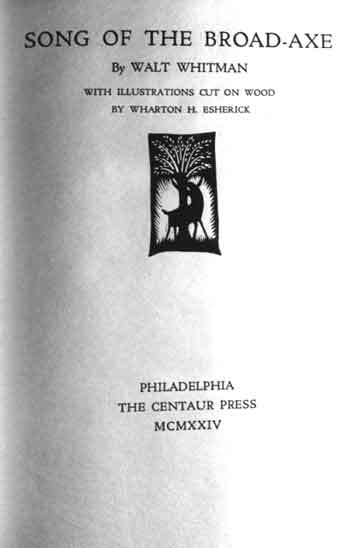

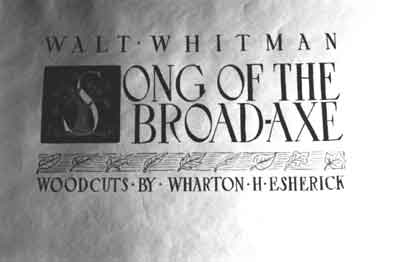

In 1924, the Centaur Press published its first book, Walt Whitman’s poem, Song of the Broad-Axe, with woodcuts by Esherick. The title page bears the Centaur Press logo by Esherick. The colophon page reads: "The first book of the Centaur Press published during the autumn of MCMXXIV at Philadelphia. The edition is limited to four hundred copies, of which three hundred and seventy five are for sale." Esherick had prepared a complete hand-lettered "prototype" of Song of the Broad-Axe that contains many unusual design elements that were not incorporated into the published book, which was designed and printed by Frederic Warde at the Princeton University Press.

The second Centaur Press book, published in 1925, was D.H. Lawrence’s Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine, which predates the English edition and includes an Esherick woodcut porcupine at the lower right corner of the half title page.

Esherick’s next two book projects for the Centaur Press were more substantial. Yokohama Garlands, a volume of poetry by A.E. Coppard, contains 24 "vignettes" by Wharton Esherick, woodcuts screened for printing that appear to be delicate line drawings. Yokohama Garlands, published in an edition of 500 copies in 1926, was designed and printed by Elmer Adler at the Pynson Printers, and was included in the "Fifty Books of the Year" selected by the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

For The Song of Solomon, Esherick prepared 30 woodcuts, including a circular woodcut title-page, as well as a decorative medallion for the front cover, and a stylized design for the back cover. He made not one but two complete prototypes. In the

prototype that most resembles the finished book, Esherick’s title page indicates the work of the artist, but the finished book bears only the circular woodcut. Esherick’s illustrations are erotic in nature. In 1927, The Song of Solomon was published in an edition of 525 copies printed on Japanese paper.

Esherick made a series of linoleum block prints for Emily Clark’s Stuffed Peacocks, published by Knopf in 1927. The following year, Esherick created a sequence of nine woodcuts for As I Watched the Ploughman Ploughing, a poem by Walt Whitman set to music by Philip Damas, and issued in an edition of 200 copies. Four of Esherick’s illustrations of rural themes for this book were reprinted in the February 1929 issue of Vanity Fair.

Esherick’s connections with Philadelphia society brought him his next book commission. Amory Hare asked him to illustrate her play, Tristam and Iseult, and Esherick prepared 10 linoleum block prints for the beautifully produced edition of 450 signed copies published by the Slide Mountain Press.

Three later works illustrated by Esherick include vignettes for a memorial poem, Bright Mariner, by Katherine Garrison Chapin (1933), illustrated below; woodcut illustrations for the poem "Turkey Gobbler Land" by Thomas Caldecat Chubb (1934); and Thwarted Ambitions by Robert Lane Anderson, son of Sherwood Anderson. Thwarted Ambitions (1935), which includes a foreword by Sherwood Anderson, reprints a humorous newspaper article reporting small town legal proceedings arising from the pasturing of heifers and steers.

By this time, Esherick’s interests had turned to furniture and sculpture, the areas in which he would gain his greatest acclaim. From his modest carvings on picture frames and the edges of tables, Esherick had progressed to more elaborate carvings and the design of pieces of furniture that would reflect his preference for organic forms and natural lines. In his sculpture, Esherick had abandoned classical methods in favor of carving directly in wood; while he frequently chose exotic tropical woods for sculptures in the late 1920s, increasingly he began to make use of local woods: oak, cherry, walnut, and pine from nearby forests.Sculpture, Furniture, Architecture

In the middle 1920s, Esherick and his wife and become involved with the Hedgerow Theatre, a professional company that converted the guild hall of the nearby Rose Valley arts and crafts community into a forum for producing avant-garde plays. Esherick carved posters for Hedgerow productions (including The Emperor Jones) and built furniture for the theater. He also made prints and sculptures inspired by theatrical subjects.

In 1926, Esherick built a new studio building on the wooded hillside above the farmhouse. This gave him a larger work space and also served as sleeping quarters in the summer, when his wife and three children went to the Adirondacks and the main farmhouse was rented.

In the late 1920s, Esherick began moving away from the Arts and Crafts influences as he became interested in German Expressionism. Hard edges and flat surfaces appeared in his work, and he made a trip to Germany in 1930 to see what German sculptors were doing. Esherick produced a number of expressionist furniture pieces between 1931 and 1933, as well as stage sets for the Hedgerow Theatre, and a series of sculptures.

This expressionist period gave way in 1934 to what can be termed the mature Esherick style of rounded corners, undulating forms, and natural shapes. In 1935, he received a commission from Judge Curtis Bok for some bookshelves. This work eventually grew to include two walls of books cases, doorways, a unique spiral staircase, a small library room, a paneled music room, an office and numerous items of furniture for the Bok house in Gulph Mills, Pennsylvania. At the height of the Bok commission, Esherick employed 11 workers, including cabinetmakers, masons, a blacksmith, a weaver, and others. The Bok house no longer exists but many of these pieces were removed to museum collections prior to its demolition.

In the mid 1930s, Ford Madox Ford visited Esherick’s hillside retreat:

A dim studio in which blocks of rare woods, carver’s tools, medieval looking carving gadgets, looms, printing presses, rise up like ghosts in the twilight while the slow fire dies in the brands ... Such a studio built by the craftsman’s own hands out of chunks of rock and great balks of timber, sinking back into the quiet woods on a quiet crag with, below its long windows, quiet fields parceled out by the string-courses of hedges and running to a quietly rising horizon ... such a quiet spot is the best place to think in.In 1940 Esherick removed the massive oak spiral stair that connected his studio to his loft bedroom and sent it, along with several pieces of furniture, to the New York World’s Fair. The Pennsylvania Hill House exhibit introduced Esherick’s work to a national audience but few commissions resulted in that time when people were preoccupied with the threat of war. He continued to work on sculpture and occasional design commissions. In the postwar years, Esherick gained a new generation of followers, and designed chairs for production by a local cabinetmaker, as well as hi-fi cabinets, kitchen objects, and other items. The New York Architectural League awarded him its gold medal in 1954 for his furniture and interior designs.

And let Esherick be moving noiselessly about in the shadows, with a plane and a piece of boxwood, or swinging backwards the lever of his press, printing off his engravings. Or pouring, a hundred times, heavy oil and emery powder on one of the tables he has designed, and rubbing it off with cloths to get the polish exactly true, and bending down again and again to see the sheen of the light along the polished wood ... Those are the conditions you need for thought. Because they present to your mind neither success nor failure, but conditions, coeval with the standing rocks and the life of man. There have always been craftsmen and the craftsmen have always been the best men of their time because a handicraft goes at a pace commensurate with the thoughts in a man’s head. [Described in Great Trade Route, 1937]

In 1956, Esherick used a legacy from an aunt to build a larger workshop next to his studio, and a 1958 retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Craft in New York City (Now the American Craft Museum) resulted in wider exposure and many new commissions. Esherick’s principal sculpting tool was the axe, but by the late 1960s, he could no longer wield it with the necessary control. His last major sculpture, Rhythms II, a graceful form shaped from the trunk of a cottonwood tree, was carved by workers using chainsaws at Esherick’s direction. Esherick continued working until his death on May 6, 1970.

After Esherick suffered a stroke in 1967, his children purchased his property to ensure that he would be able to live in his studio for his remaining years. Following his death, his heirs determined to maintain Esherick’s studio and collection intact. The Wharton Esherick Museum, established in 1972, is housed in the 1926 studio building, and preserves works from the whole of Esherick’s career, including furniture, sculpture, prints and books, as well as many of the original printing blocks carved by Esherick.The Wharton Esherick Museum

Several books have been published by or in association with the museum, including The Wharton Esherick Museum Studio and Collection (Paoli: The Wharton Esherick Museum, 1977; second edition, 1984); Drawings by Wharton Esherick, compiled, edited, and with an introduction by Gene Rochberg (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1978); and Half a Century in Wood by Mansfield Bascom (Paoli: The Wharton Esherick Museum, 1988). Limited edition restrikes of some of the woodcuts have been produced, following a custom initiated by Esherick. Efforts are under way to reprint Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk.

[The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Robert Leonard, director of the Wharton Esherick Museum, and Mansfield Bascom, curator, in preparation of this article. The mailing address is: The Wharton Esherick Museum, P.O. Box 595, Paoli, Pennsylvania 19301. The Wharton Esherick Museum website is found at http://www.whartonesherickmuseum.org/. Another well designed website devoted to the artist is found at http://www.levins.com/esherick.html.]

Esherick’s illustrations appeared in books and periodicals between 1922 and 1935, with a few later items. The following chronological list describes the books featuring Esherick illustrations. Further information is contained in Prints by Wharton Esherick, the catalogue of a 1984 exhibition at the Woodmere Art Museum in Philadelphia, which provides a detailed alphabetical listing of 214 prints (by title) and 181 illustrations for books (in order of appearance).An Esherick Checklist

1. Rhymes of Early Jungle Folk by Mary E. Marcy. Chicago:

Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1922.

Illustrated with 71 woodcuts by Wharton Esherick.

2. Song of the Broad-Axe by Walt Whitman. Philadelphia: Centaur Press, 1924. Illustrated with 20 woodcuts by Wharton Esherick, including dust jacket and illustrations on boards. Edition of 400 copies. The first book of the Centaur Press.

3. Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine by D.H. Lawrence.

Philadelphia: Centaur Press, 1924.

The half-title bears a woodcut Porcupine by Esherick. Edition of 925

copies, bound in marbled boards, with slipcase. The second book of the

Centaur Press.

4. Yokohama Garlands and Other Poems by A.E. Coppard.

Philadelphia: Centaur Press, 1926.

Illustrated with 24 vignettes by Wharton Esherick. Edition of 500 copies.

5. The Song of Solomon. Philadelphia: Centaur Press, 1927.

Illustrated with 30 woodcuts by Wharton Esherick. Edition of 525 copies,

bound with orange cloth spine and white boards embossed with colored designs

by Esherick.

6. Stuffed Peacocks by Emily Clark. New York: Alfred A.

Knopf, 1927.

Illustrated with eight linoleum cuts by Wharton Esherick. Dust jacket

illustration by Esherick.

7. As I Watched the Ploughman Ploughing by Walt Whitman

and set to music by Philip Damas. Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company,

1928.

Illustrated with nine woodcuts by Wharton Esherick, including cover

illustration. Edition of 200 copies.

8. Tristam and Iseult by Amory Hare. Gaylordsville: Slide

Mountain Press, 1930.

Illustrated with 10 linoleum cuts by Wharton Esherick. Edition of 450

copies printed on Bishopstoke hand made paper, each copy signed by the

author and artist.

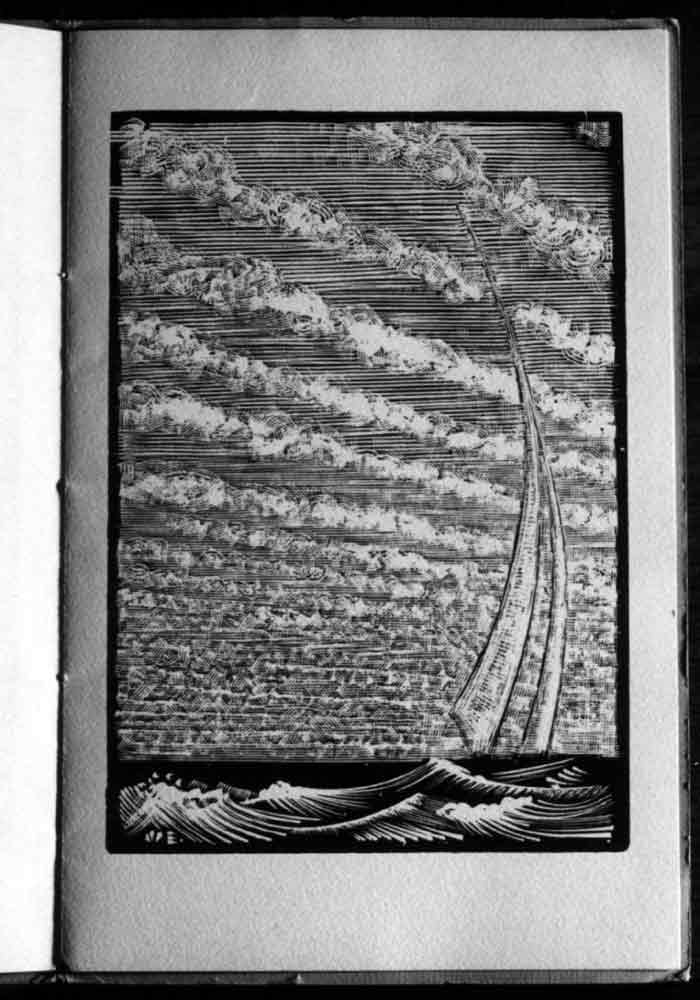

9. Bright Mariner by Katherine Garrison Chapin. New York:

Duffield and Green, 1933.

Esherick produced three woodcut illustrations on yachting themes for

this memorial pamphlet: a small vignette of a sloop tipped onto the front

wrapper; a full page print (illustrated above), and a small vignette of

a sloop on calm seas for the last printed page. Not listed among the books

in Prints by Wharton Esherick.

10. Thwarted Ambitions by Robert Lane Anderson. Foreword

by Sherwood Anderson. Philadelphia: Centaur Book Shop, 1935. Printed by

the Marion Publishing Company, Marion, Virginia.

Illustrated with six woodcuts by Wharton Esherick, including cover

illustration. "Second Edition" so indicated on the copy examined.

Copyright 2001 by Henry Wessells. Links updated January 2013. All rights reserved.]