January 2007

31 January 2007

Book Bloggers before the internet (second in an occasional series)

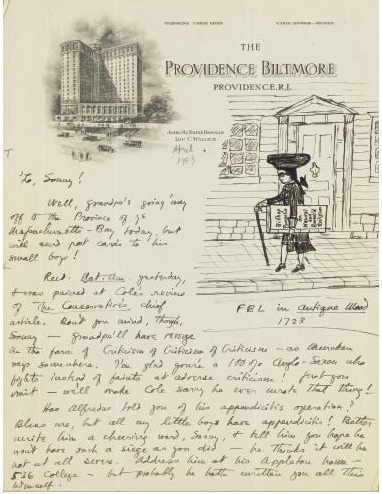

Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890-1937) was an American author who spent most of his life in Providence. A short biography by S. T. Joshi can be found here (the long version, H. P. Lovecraft : A Life , is a thick 700-page book published by Necronomicon Press in 1996). Although he is sometimes viewed as “ the recluse of Providence ” he was perhaps not so reclusive as it seems. He was active enough in amateur journalism to qualify as a proto-blogger on that basis alone, but letter-writing was his preferred medium. Last month a substantial collection of manuscripts of H. P. Lovecraft sold at auction in New York, including the autograph manuscript of The Shunned House and a 500-page collection of 50 letters, from H. P. Lovecraft to Frank Belknap Long, 1922-1931, each averaging 10 pages, with one letter 60 autograph pages in length.

The reappearance of these letters to Long — occupying many pages in the five-volume Selected Letters — tends to confirm a position I took in a review of the H. P. Lovecraft and Donald Wandrei correspondence, Mysteries of Time and Spirit (Night Shade Books, 2002), where I wrote :

Even if it is through his fiction that one first comes to Lovecraft, he was fundamentally a letter writer who, from time to time, would turn out a story or an essay or an account of his travels. [. . .] we all know how many words he could fit onto a penny post card. That any of Lovecraft’s fiction saw publication during his lifetime seems to have been almost accidental. His letters are filled with deprecations and protestations of disinterest, to be interpreted as the reader sees fit, but one has to assign a certain degree of truthfulness to his statements.

Having been able to examine the Long correspondence, I am thoroughly persuaded that Lovecraft lived for his letters ; yet I find them for the most part only slightly above the level of the amateur journalism (and in no way comparable to the half-dozen best fantastical tales he wrote). But what a blogger on architectural preservation the author of The Shunned House would be.

I will happily publish (and comment upon) any reasonably phrased dissent this entry provokes.

30 January 2007

A picture of one of the shelves in the office of Temporary Culture and the Endless Bookshelf :

I mentioned calligrapher Edward Johnston earlier. His apple-green letter W at the beginning of the Doves Press Hamlet is one of the marvels of the early twentieth century. In addition to the delightful image of Johnston in his studio with a sign reading “ Preoccupied ” on the door to warn others away, Priscilla Johnston records the following exchange on p. 148 of Edward Johnston (Faber and Faber, 1959) :

Looking back, the most surprising thing is not that it took so long but that it was ever finished at all. Nearly forty years later, when he was working on another book — which seemed to bear some resemblance to Penelope’s web — his daughter, Bridget, remarked that she wondered how he had ever finished the first, to which he replied ‘It was comparatively easy then because I knew nothing about the subject.’ [. . .]

Earlier

this month, I read Bleak House by Charles Dickens. I

had never read it before, but after two nudges, one from a friend

who was reading

the book, and the other, simultaneously, from references to it

in The

Ghost Map by Steven Johnson (Riverhead, 2006),

I was ready to remedy that gap in my education.

I was engaged from the postmodern first paragraphs :

Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes — gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. [. . .] Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows ; fog down the river, where it rolls deified among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs ; fog lying out on the yards and hovering in the rigging of great ships ; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards ; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin ; fog cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little ‘prentice boy on deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon and hanging in the misty clouds.

And how about this crunchy, complex (and subtly verbed) sentence from Bleak House (Chapter 26) :

Behind dingy blind and curtain, in upper story and garret, skulking more or less under false names, false hair, false titles, false jewellery, and false histories, a colony of brigands lie in their first sleep.

And Inspector Bucket ! Spontaneous combustion ! And Tom-all-Alone’s ! And even the irritating aspects of Esther’s Narrative . . . . And how, after hundred of pages, even the loosest narrative thread is pulled tight in a sudden knot of circumstances. Wow ! What a book.

Not only because I am the publisher of one of them do I commend Jeff VanderMeer’s column at Locus Online : 2006: Twelve Overlooked Books. All of us readers need to be prompted look outside the usual shelves.

28 January 2007

It is the hardest thing in the world to shake off superstitious prejudices : they are sucked in as it were with our mother’s milk ; and, growing up with us at a time when they take the fastest hold and make the most lasting impressions, become so interwoven into our very constitutions, that the strongest good sense is required to disengage ourselves from them.

The quiet drama in his account of the felling of the Raven-Tree ; his joy at seeing the first returning swallows ; the emphasis on observation : the book challenges me to think about the discernible traces of the natural world in my life. I have the Scolar Press facsimile of the first edition at home ; in the shop we have a copy of the real thing.

Last summer I turned up a copy of the collected works of South African writer Eugène Marais, whose writings I first encountered through the late Reno Odlin, who had sent me a photocopy of “ The Sacred Beads of the Bavenda ” over a decade ago. Leon Rousseau’s biography, The Dark Stream. The Story of Eugène Marais (Jonathan Ball, 1982) is fascinating and ranges from Johannesburg to 1890s London to the Waterberg and rural South Africa. Marais was a poet and journalist at the heart of the literary revival of the Afrikaans language ; he spent several years in close observation of baboons (during which period Marais essentially formulated the modern discipline of comparative ethology, though his pioneering status was not fully recognized until 1969) ; and he was a long-term opium addict. Guy Davenport, in The Geography of the Imagination , mentions an essay Marais published in 1914 — “ Notes on Some Effects of Extreme Drought in Waterberg ” — and it was worth the wait. His writings in English are of crystalline simplicity ; every now and again I dive into an Afrikaans piece to see what I think I might understand of it. The concluding sentences of “ Notes on Some Effects of Extreme Drought in Waterberg ” are masterly :

It does not seem possible enough water can ever again fall to damp or even to cool this parched and cracked earth and to fill these moats of burning sand. Optimism suggests that it is only the great tidal swing of nature exemplified ; that we are at the lowest point of the periphery, and that from now onwards it must rise steadily to better things. But at the back of one’s mind remains the pessimistic conviction, apparently borne out by every fact observed, that the oscillations of the pendulum are gradually lessening round the deadpoint.

[Note added later] The full text of the essay is available here : https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/mara002vers01_01/mara002vers01_01_0183.php

— — — —

A Whimsy :

I am:

James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice B. Sheldon)

In the 1970s she was perhaps the most memorable, and one of the most popular, short story writers. Her real life was as fantastic as her fiction.

Which

science fiction writer are you ?

[courtesy of Don Webb who is blameless]

27 January 2007

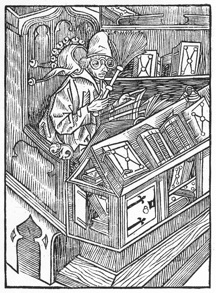

Woodcut from the German edition of The Ship of Fools (1494), reproduced in The Book-fool. Bibliophily in caricature (1934), a supplement to The American Book Collector magazine edited by Charles F. Heartman, with caricatures of collectors from 1494 to modern times.

This brings me to the first instalment in an occasional series:

Book Bloggers before the internet

Charles

F. Heartman (1883-1953) was a German-born bookseller, writer and magazine

publisher. Active from just before the First World War through the

early 1950s, Heartman was a specialist in book and manuscript Americana

who wrote frequently on bibliographical subjects. He was publisher

or editor of a sucession of magazines in the 1920s, including The

American Book Collector. Heartman has been overshadowed by the

flamboyant Dr. Rosenbach of The

Rosenbach Company (the link is to Mark Mulcahy & Ben Katchor’s

musical biography) but Heartman’s publications and prickly opinions are

still of

interest.

I have come across a number of Heartman’s bibliographical publications ;

most of the facts I have at my command are from the excellent article

by Joel Silver (Curator of Rare Books at the Lilly

Library) entitled “ Charles Heartman and the Americana Collector ”

(AB

Bookman’s Weekly for

13 April 1998), which includes extensive quotations from Heartman’s

editorials, and where Silver writes:

The explosive growth of the internet as a bookselling and book buying tool has further blurred the line between dealer and collector, and it has also aided consdierably in the dissemination of ludicrous book descriptions.

I also think that Heartman might have found, in today’s electronic environment, a medium well-suited to his “ Comments and Arguments ”, in which publication is instantaneous, the audience is almost unlimited, and free and unbridled expression and exchange is an expected and essential part of net culture. “ That damned Heartman ” would fit right in, and I’m sorry I’m not able to see it.

Two books that have just landed on my reading table : London. City of Disappearances edited by Iain Sinclair (Hamish Hamilton, 2006) and A Specter is Haunting Europe. A Sociohistorical Approach to the Fantastic by José B. Monleón (Princeton University Press, 1990). Both look interesting. Watch this space. [HW]

26 January 2007

I saw my friend Ernest Hilbert at the Lexington Avenue antiquarian book fair this afternoon. He is a colleague in the world of rare books and a great literary chum. He lives and breathes contemporary American poetry and his literary website is E-Verse Radio. We joked about strategies to make the Endless Bookshelf a household name. I hope that he will one day send me his list of recent reading.

I am pleased to have been invited to read with my friend Wendy Walker at the launch of the new issue of Circumference, a journal of poetry in translation based at Columbia university (website is a bit out of date). With Rabia Zbakh, Wendy has translated Abdelkrim Tabal’s Distant Flames, produced as an artist’s book by Florence Neal. On Thursday 8 February (7:00 p.m.), translators Emily Moore, Wendy Walker, and Matthew Zapruder will read poetry translated from Spanish, Arabic, and Romanian at the Swiss Institute — Contemporary Art, 495 Broadway, 3rd Fl., N.Y.C. (T. 212.925.2035). I’ll be reading the Arabic originals.

25 January 2007

It’s worth making an effort to get to see the current exhibition at the New York Public Library, Ehon. The Artist and the Book in Japan, curated by Roger S. Keyes. Subtle colors, adventurous forms, beautiful materials, and a constant reminder that to make a book is a very human achievement. The forty-foot scroll in shades of grey and black ; the frog ; and the woodblock banana leaves and portrait of Bodhidharma filled me with wonder and ambition (through 4 February).

— Marian Engel. Bear. (McClelland & Stewart, 1976; Godine, 2003). This is really quite some book. The protagonist is a rather cloistered librarian who journeys north to a remote islet and the octagonal house of the Colonels Cary, the first of whom built the folly and imported its library in the 1830s, the last of whom was a woman named “Colonel,” and all of whom kept a bear. “Not a toy bear, not a Pooh bear, not an airlines Koala bear. A real bear. [. . .] indulged herself by lazily scanning the shelves trying to comprehend the books’ scope and order. She was presented with a sharp and perhaps typical early nineteenth-century mind : encyclopaedias, British and Greek history, Voltaire, Rousseau, geology and geography, geophysical speculation, the more practical philosophers, sets and set of novelists. She wondered where else there was such a perfect library for its period.” The librarian catalogues the library for the Institute — a succession of curious discoveries deftly rendered — and follows the advice of the ancient Indian woman about how to get to know the bear, with startling consequences. A rich and brilliant book, really unsettling.

24 January 2007

‘Nice ? It’s the only thing,’ said the Water Rat solemnly, as he leant forward for his stroke. ‘Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing — absolutely nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats. Simply messing,’ he went on dreamily : ‘messing — about — in — boats ; messing — —’

‘Look ahead, Rat!’ cried the Mole suddenly.

It was too late. The boat struck the bank full tilt. The dreamer, the joyous oarsman, lay on his back at the bottom of the boat, his heels in the air.

‘— about in boats — or with boats,’ the Rat went on composedly, picking himself up with a pleasant laugh.

from The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

It’s the only thing. So here goes.

— A Brief Illustrated History of the Bookshelf, drawn & written by Marshall Brooks (Birch Brook Press, 1998), is a beautiful book that conveys information with economy and whimsy. Brooks traces the continuity from ancient Rome and Mesopotamia to the chained books of Hereford Cathedral, the ventilated shelves of the Library of Congress, and the shelves of a shack on the Nantucket dunes. (I was pretty certain I extolled its virtues in a Read This ! for NYRSF but can find no record of that essay, which may not have survived data migration.) I have given away several copies of the book ; in the copy I have on my shelf now, I have tucked in a copy of an illustration of Judge Dee in His Library by R. H. van Gulik, and I must have one of an Arabic library somewhere, too.

The Endless Bookshelf, because I live in a small house : I have one very small glass front two-shelf bookcase downstairs, books on top of that, half a shelf of reference books & poetry near the stereo, seven shelves of books in closets, eleven shelves of books in the attic as well as the nine boxes and two filing cabinets that still have not been unpacked (and four shelves of books in the shed). I keep some books, but others move on to find a place on someone else’s shelf.

Not long ago I finished reading the two latest works of fiction by Rudy Rucker : Mad Professor. The Uncollected Stories, (Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2007), wild stories and thought experiments, and his novel Mathematicians in Love (Tor, 2006). Rucker names four greats in his preface to Mad Professor : Einstein, Plato, William Burroughs, and Robert Sheckley ! He’s great at conveying ideas of the pop culture of the future, and at inventing the specialized jargon of sub-groups (and not shy about political satire, too). I see that I have just made a decision that may run contrary to all currents in blogging — to link to author and small press and individual websites, but not to big corporate sales sites. I presume that anyone reading can choose how to obtain current commercially published books, or not. We’ll see.

electronym : wessells

at aol dot com

Copyright © 2007 Henry Wessells

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.