December 2013

17 & 30 December 2013

That Time of Year : Best Book of 2013

— Greer Gilman. Cry Murder! in a Small Voice. Small Beer Press, [2013]. vi, 53, [5] pp. Jacobean crime tale in dazzling prose style. The Best Book of 2013.

The tale is swiftly told : a rich peer — evil and depraved, if words still have meaning — took his pleasure in killing little boys ; a drunken poet, grieving, went down these mean alleys to end this wrong, with the help of a boy who knew one of the victims. But this is not all, this is almost nothing : for Gilman’s gesture and language — the dance of paper figures, and an orange offered in winter — are magic. Read carefully, taste the words upon the tongue. Not everything is what it seems.

What is a story but the dance of words ? Greer Gilman’s language is always demanding : even short declarative sentences resonate with layers of meaning. The longer cadences are nimble, tricky on the tongue and in that place in the brain where deliberate allusions * float like wisps of smoke on a winter morning or snap as flags in a furious gale. It is hugely ambitious to encode so much of the Elizabethan theater into a murder mystery staged upon the hinge of the modern world. That Gilman accomplishes this tale within the space of fifty-two pages is brilliant, contrarian, and wholly admirable.

From the rafters, bright-leaved as a wood in fall, unfallen, hung a company of players, masque and anti-masque. In little : mere idolatries, no greater than his hand. A puppet show. Some cut from ballad sheets ; some drawn by a childish hand ; all painted : knights, gods, shepherds, witches ; bears and dragons, Mab and Merlin and the rapt Prosperina. Fantastical, this meddled work — aye, Willfully — to graft such hedgerow Englishry on ancient stock, imp out the laurel with the hawtree. Scene : a wood near Athens. Crinkum-crankum. He would have mocked them as a pack of cards ; but in the drowning light, they seemed like spirits. Shades of — Bah ! a cheat of fantasy. Bad glass, as green as standing water, and an ill-fit frame, no more a wind in here. But whispering, they stirred.

That paragraph is as beautiful as the opening of chapter six in The Blue Star , “ Night and Day ; The Place of Masks ”, when Rodvard and Lalette enter the costume-maker’s loft, or any other passage from any book you may choose : inseparable from the narrative threads of Cry Murder ! , not a word out of place. It is also rather intricately bound to the entire fabric of English literature. Vast libraries are filled with literary responses to Shakespeare : Johnson, Browning, Kipling, Bloom, and others, in a long procession of authors, critics, scholars. Greer Gilman gives us a taste of how Shakespeare played in his own time, and how his words rang to one who loved him well. Gilman’s Ben Jonson is a delightful creation : flawed, fond of drink, and mourning the death of his son, but not so long retired as a soldier that he has forgotten action. Gilman’s Jonson is a figure to counter the poet’s self-portrait in his last years, “ a tardie, cold / Unprofitable Chattell, fat and old, / Laden with Bellie ”. James Joyce read deeply of Jonson ; so has Greer Gilman, and we are infinitely richer for it.

The Best Book of 2013.

——

* I suspect an entire concordance or glossary of citation could be compiled, larger than Cry Murder ! Let it be from some one else’s pen.

— — — —

current reading

— Norman Rush. Subtle Bodies. Knopf, 2013.

— Twenty-First Century Science Fiction. Edited by David G. Hartwell and Patrick Nielsen Hayden. Tor, 2013. Gift of [LZ].

— — — —

Tenacious clinging to the right of private judgement is an English trait, that a mere grammarian may not presume to deprecate . . .

H.W. Fowler, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, 1926

— — — —

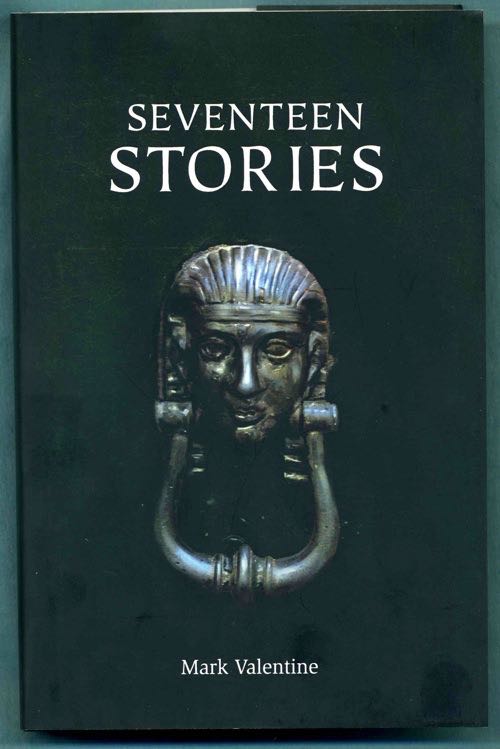

— Mark Valentine. Seventeen Stories. Swan River Press, 2013.

Books are dangerous things in the writings of Mark Valentine. Seventeen Stories demonstrates the wide range of his considerable talents. He is attentive to place and to the power of obsession, but one of his true gifts is an ability to suggest modes of artistic expression. That these new media would likely be impossible to accomplish in the ordinary world in which we dwell is nothing. In his stories, as one reads of cataloguing dreams, searching for an elusive culinary ingredient, or attending an unusual musical performance, Valentine makes the spark of recognition leap from the page to the reader. It is useful to cite Joanna Russ here :

[. . .] James Blish’s dictum that ideas alone are worthless, what counts is ideas about ideas. Sex, like all primary experiences, can be named directly but not described directly; one can only describe its effect on people, its experiential dimension, so to speak. In the newness of taboo-breaking, many writers forget this [. . .]. What matters is not organ grinding but the explosions sex produces in the head.

How tiresome it is, sometimes, to read endless tales of writers struggling to perfect their art. Valentine has evolved a resilient and infinitely mutable solution, though : his stories of peculiar quests and arcane lore get their protagonists out from behind a desk and into country houses (“ An Incomplete Apocalypse ”), isolated Yorkshire graveyards (“ The Tontine of Thirteen ”), and the salt pans of the French coastline.

Valentine’s other notable gift (inseparable from this talent for evoking new forms of expression) is the literary exploration of friendship. On the last page of my copy of The Collected Connoisseur by Mark Valentine & John Howard (Tartarus Press, [2010]), I have written a list of the literary record of artistic creations the book embodies : architecture, cartographies of ice and silence and mist, celestial bodies, cemeteries, cigarettes, cinemas, clouds, countries and enclaves of preserved history, dance music, drowned kingdoms, etchings, liturgies, manuscripts, matchboxes, ornamental stonework, poetry, photographs, postage stamps, rocking horses, scientific instruments, sculptures and cubist furniture, tableaux vivants, and membership societies.

The Collected Connoisseur is, fundamentally, a book about friendship. Seventeen Stories contains several stories that evoke this vocabulary : how shared aesthetic experience builds solid foundations of friendship. Valentine understands that it is not only in spoken professions of affinity but in silence and space that friendship grows. In Seventeen Stories as in other works by Valentine, the revelations are often to be classed under the heading of quiet observations, but several of these tales have a sharp edge to them that I have not seen in earlier stories. “ Without Instruments ” (2012) is one of the strongest stories in the book. In addition to being a delightful examination of “ the wilful admirers of the obscure ”, it is a superb, truly haunting tale : “ The Kerastion ” by Ursula K. Le Guin is the only story I have read that is even remotely similar ; but where Le Guin’s jeu d’esprit is a funeral ritual, the lost work of John Ruthven in “ Without Instruments ” is “ a living composition ” and a signpost to a new way of seeing.

There are three detective stories here : two are deft pastiches of Conan Doyle and M.P. Shiel, and the third something more. In “ The Return of Kala Persad ”, Valentine creates a deftly balanced and fully autonomous voice for the eponymous vegetarian Hindu sleuth in Edwardian London whose earlier adventures were narrated by a pukka sahib in The Divinations of Kala Persad and Other Stories by Headon Hill (1895). To a twenty-first century reader, the original series reveals all too clearly the prejudices and ignorances of the day. Valentine’s liberation of Kala Persad is a careful tightrope act, offering unmediated Anglo-Indian cadences while avoiding twee constructions. Perhaps there will be more.

A number of the stories collected here (including “ The Axholme Toll” and “ The Other Salt” ) have seen publication only in books with exotic imprints (and very narrow circulation). Swan River Press has a good distribution record and Seventeen Stories will make Valentine’s work more widely available : a good place to start.

— — — —

recent reading

— William Zachs. ‘ Breathes There the Man ’ Sir Walter Scott 200 Years since Waverley. An Inaugural Exhibition. Edinburgh, 2014 [i.e., November 2013]. Illustrated catalogue.

— Nathaniel Philbrick. Why Read Moby Dick ? [2011]. An exemplary short book on a vast subject : revelling in the text, and, as in the case of the correspondence of Melville and Hawthorne, suggesting (with citations) where to go to enrich one’s own understanding of the book and its context.

— Ishmael Reed. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down [1969]. Alison & Busby, [1971].

— Donna Tartt. The Goldfinch. Little, Brown and Company, [2013]. At the point where the protagonist declared, “ All I wanted was to scrape by ” (page 412), your correspondent flinched, but persevered. The narrative structure and tone (of deadened entitlement) closely resemble those of The Magicians by Lev Grossman (2009) ; with opiate addiction and the margins of the criminal underworld in place of magic and an alternate reality.

— — — —

alphabetical list of a few good books read in 2013

— Kingsley Amis. The Green Man [1969]. Introduction by Michael Dirda. New York Review Books, [2013].

— Paolo Bacigalupi. The Windup Girl [2009]. Night Shade Books paperback, [2012].

— Max Beerbohm. The Illustrated Zuleika Dobson or an Oxford Love Story [1911] with 80 illustrations by the author. Yale University Press, 1985.

— Susannah Clapp. A Card from Angela Carter. Bloomsbury, [2012].

— Avram Davidson. The Wailing of the Gaulish Dead. Preface by Eileen Gunn. The Nutmeg Point District Mail, 2013.

— Graham Joyce. Some Kind of Fairy Tale. A Novel. Doubleday, [2012].

— Charles Robert Maturin. Melmoth the Wanderer [1820].

— [Lady Morgan]. The Wild Irish Girl. A National Tale. By Miss Owenson. In three volumes. The third edition. London, 1807. Note here.

— Jeremy Norman. Scientist, Scholar & Scoundrel. A Bibliographical Investigation of the Life and Exploits of Count Guglielmo Libri . . . . The Grolier Club, 2013.

— Flann O’Brien. The Poor Mouth. A Bad Story About the Hard Life [1941]. Translated from the original Irish by Patrick C. Power. Illustrated by Ralph Steadman. [1973]. Dalkey Archive Press paperback, [2008].

— — — —

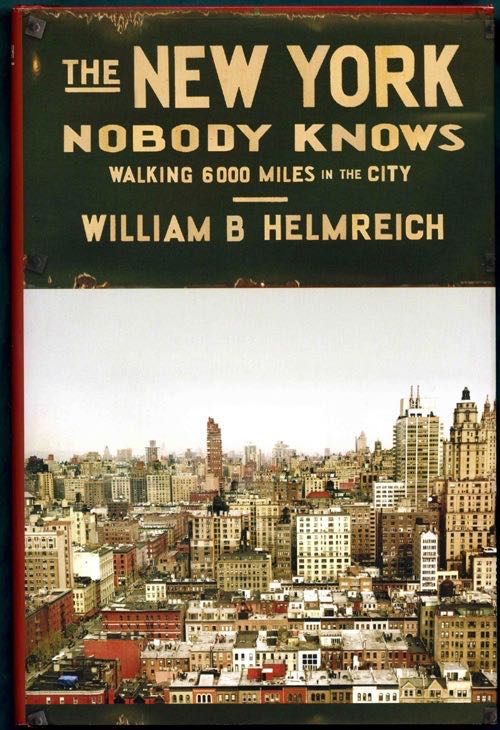

— William B. Helmreich. The New York Nobody Knows. Walking 6,000 Miles in the City. Illustrated with maps, photographs. [xxiv], 449 pp. Princeton University Press, [2013].

Walking is critical to the task because it gets you out there and lets you get to know the city up close. However, you cannot merely walk through a city to know it. You have to stop long enough to absorb what’s going on around you.

Fascinating survey of the ethnography and social history of contemporary New York City, richly documented in anecdote and fact. Helmreich ranges throughout the five boroughs and across class and ethnic barriers with the affability of an older guy who knows how to get people talking : “ What is amazing to me is that this individual can meet me, a stranger whose language he doesn’t speak, invite me into his apartment . . . ” And we’re off on another adventure among immigrants, in a gentrifying hotspots, and in areas known only to residents. If at times, Helmreich seems almost pollyannaish in his view of the city’s success and resilience, he comes right back down to earth with statement such as this, on gentrification : “ I’ve concluded that most gentrifiers do not really mix with the natives, often preferring people who, like them, are new to an area instead. ” He is alert to the homogenizing effect of gentrifying neighborhoods, “ as the overall cost of living makes it possible for only the well-off to remain there ”, and notes the difficulty in tracking those who have left for economic reasons. While Helmreich occasional looks at the porous border between Queens and Long Island, Hoboken and Jersey City are curiously invisible in his search to understand what makes the city function. The consideration of homelessness is inadequate (unlike Helmreich’s explicit recognition that the large industrial areas of the city have not been studied).

The strength of the book, and its chief pleasure for the reader, is in the specificity of Helmreich's encounters with residents, politicians, and community leaders. The notes are as rich in story as the main text. The New York Nobody Knows is an invitation to walk.

— — — —

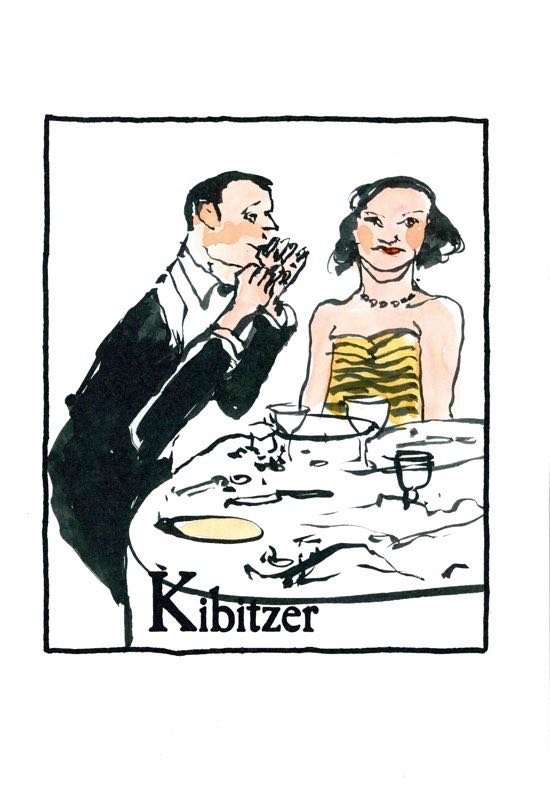

— Robert Andrew Parker. Yiddish Lexicon. Volume One. Words that have practically entered the English Language. Ink Inc., 2013. Edition of 100 copies signed by the artist. Collection of thirty-six hand-colored prints : visual definitions of words that are essential to living English usage. The style is a little reminiscent of William Nicholson’s Alphabet, London Types, or An Almanac of Twelve Sports from the late 1890s ; the Lexicon gives a bold interpretation of chutzpah.

— — — —

Be Very Afraid

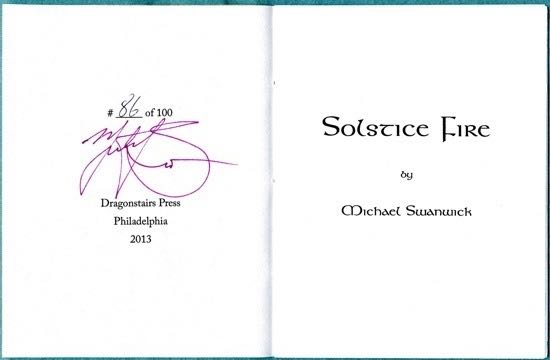

— Michael Swanwick. Solstice Fire. Dragonstairs Press, 2013. [13] pp. Edition of 100 signed copies. Collection of three very short stories, “ Bone-Fire Time ”, “ Interview with a Salamander ”, and a chilling, memorable whimsy : “ Mice Discover Fire ”.

— — — —

Unlike T.E. Lawrence, who once sent round a card stating that he would write very few letters, your correspondent, who will return to this space toward the end of January, pledges to write more letters in 2014 (N.B. the postal address is below, send a letter and I will write back).

— — — —

This creaking and constantly evolving website of the endless bookshelf : I expect that some entries will be brief, others will take the form of more elaborate essays, and eventually I will become adept at incorporating comments or interactivity. Right now you’ll have to send links to me, dear readers. [HWW]

electronym : wessells

at aol dot com

Copyright © 2007-2014

Henry

Wessells and individual contributors.

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.