August - September 2012

30 September - 1 October 2012

“ Some of them are working very hard indeed. [. . .] They are reading ! ”

— Robin Sloan. Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore. Farrar, Straus and Giroux [October 2012].

This funny and utterly up-to-date novel has everything you could ask from a book : graceful turns of phrase, secret vaults, dialogue as spoken by living beings, data old and new, a plot that integrates all of the numberless threads and allusions from first page to last, and an intelligent women who says, “ Can I see the source code ? ”

In a great opening paragraph that is a nod to the essence of science fiction adventure, Clay Jannon appears Up on Cliff — high atop a ladder in a very eccentric bookstore, and that launches this tale of a guileless, tech-savvy young man whose job as designer for a bagel start-up has evaporated. After seeing a sign in the window of Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, Clay lands a job because he is able to articulate his sincere love for a series of books he read in the sixth grade. The bookstore is larger inside than it would seem to the casual visitor, and Clay has enough sense to disregard one of the rules about the books in the back room, “ No Reading ”.

Find Girl is another standard plot element that Sloan tweaks. When Clay creates a “ hyper-targeted local campaign ” to draw people into the store, he promptly forgets it until a girl wearing a red t-shirt with a big yellow BAM ! printed on it walks in. When Kat Potente sees a model of the bookstore on Clay’s laptop, she asks the question. Kat works for a hi-tech company and takes an interest in Clay as well as in his source code : it takes a couple of hours of lignin inhalation for Clay’s pulse to calm down after she leaves. A thoroughly post-modern young woman, when Clay is unable to come to a party with her because of his work, Kat takes him along on her device, playing the imitation game with her colleagues. Before long, they find ways to spend time together, and he brings one of the bookstore’s logbooks to the crystal castle to be scanned, with surprising results.

Sloan choses names well : Tyndall, Corvina, Edgar Deckle ; and Clay’s sly asides are witty on the surface — on updating a wiki-page as a cognate of fidgeting, for example — but they are of one essence with the narrative. The minor characters have their uses, but the reader learns their skills as part of their nature. After Penumbra disappears, Clay’s friend Neel from the sixth grade, who read The Dragon Song Chronicles and played Rockets & Wizards with him, funds a trip to the secret library in New York. Kat and Clay, wizard and rogue, need a warrior for their adventure. Neel comes along and is rewarded with the opportunity of a lifetime, “ to walk through a secret passage built into a bookshelf ”. Neel has an interest in fabric and anatomy that will also prove relevant.

The secret library of the Unbroken Spine, “ hiding in plain sight ” on Fifth Avenue, is the central headquarters of a network of bookstores scattered across the globe, and funds itself through licensing a font omnipresent and intrinsicate with life, the internet, and everything. And so the next Complication is very real : “ We break letters but can’t make new ones ”. It is not sufficient to design type ; real letters are cast in matrices formed by punches — and it is these that have vanished. We are in the presence of very old data. Clay smuggles a cardboard scanner into the vault and spends the night acquiring the codex vitae of Aldus Manutius. And here is where the novel demonstrates that Sloan is working in the science fiction mode or genre. Kat Potente directs the entire worldwide resources of the hi-tech company — “ the whole system ” — to solving the code :

And then, on a sunny Friday morning, for three seconds, you can’t search for anything. You can’t check your e-mail. You can’t watch any videos. You can’t get directions. For just three seconds, nothing works, because every single one of Google’s computers around the world is dedicated to this task. [. . .] Every question you can ask a sequence of letters is being asked.

Three seconds later, the interrogation is complete.

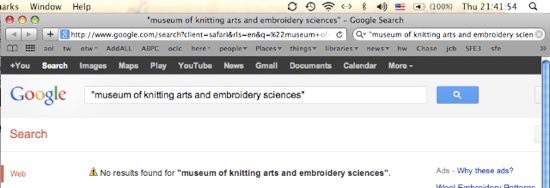

And yet this new examination of the old knowledge is, in the end, insufficient. As Neel observed earlier in the novel, “ The suburban mind cannot comprehend the emergent complexity of a New York sidewalk. ” So the expected revelation is a disappointment, merely another loop of Complication. But just when you think it is safe to cross the street, Sloan comes out with a dazzling curatorial sequence, beginning with an utterly imaginary museum — reader, I goo-gulled it :

Clay Jannon has a talent for friendship — the real engine of this novel — and it leads him to the right places. Once he is able to use Cal Knit’s Accession Table, a global database of objects and provenances, Clay finds the present custodians of the missing punches. Consolidated Universal Long-Term Storage is a vast facility in the Nevada desert, the ultimate repository of stuff. The choreography of moving storage shelves as Clay walks into the unmoving center of the warehouse is dizzying fun. That he finds the punches (stolen a century before) is of course necessary to the novel’s plot, but it also suggests an underlying fundamental optimism. That Cal Knit exists only within the pages of this novel is recognition that we dwell in an imperfect world of fleeting phenomena.

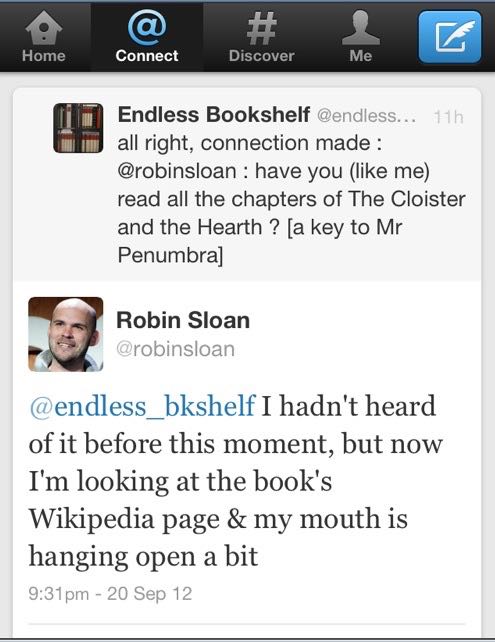

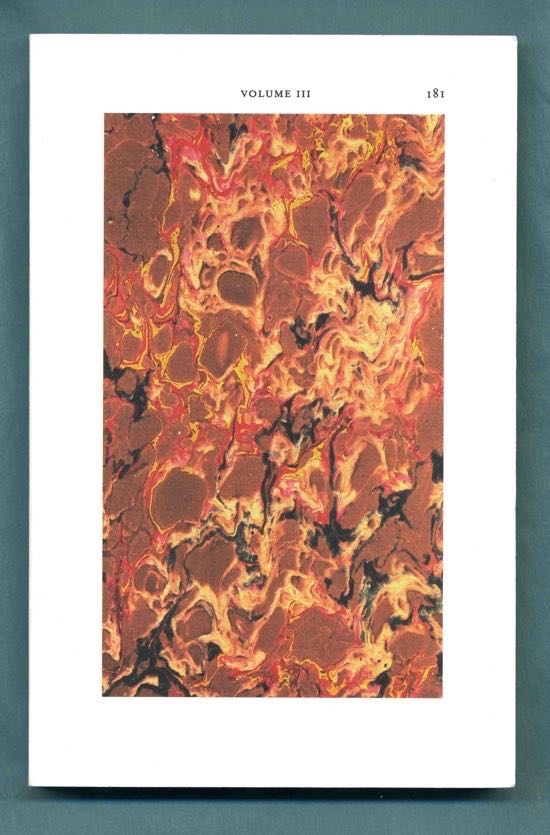

In this review I have intentionally omitted any mention of the name of the font that drives the universe of this novel. I do not think that you will find it in any standard history of printing, and yet this is a trifle, for the name is utterly true to the intellectual ferment of the times Sloan evokes. After a week of not thinking about it, the connection fell into place :

A hint of the process of indirection can be seen here.

Oh, and another thing : it is hard, in fact, impossible, to resist an imaginary book. At first encounter, The Dragon Song Chronicles by Clark Moffat seems merely to be one of those series books read and loved in childhood, but an alert reader will soon grasp Sloan’s clues that something more complex is at work here: hiding in plain sight. The mountains are a message from Aldrag the Wyrm-Father. At every stage of the plot, Clay’s connection with the Moffat book helps him find his way. This novel has a very satisfying level of internal coherence.

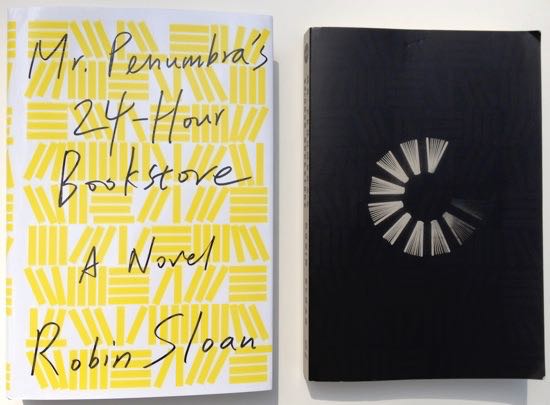

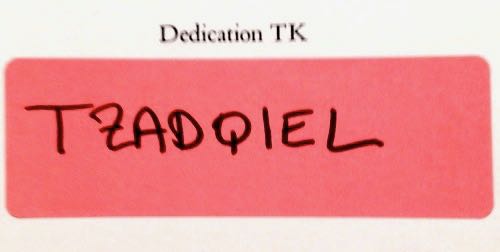

I first read this book in a proof (the dark cover at right above), in fact « TZADQIEL », one of the proofs designated by the author as a Prime :

and which, as instructed, I sent along to another reader in a far-away land who will also, I trust, report in to supply location for the data visualization Sloan promises. So I can no longer compare the proof text to the finished book (cover at left above) ; but in addition to changing the code numbers for the bookstore customers, there is a small adjustment to a bit of historical data that gave me pause when I first read it ; in the finished book the passage reads fluidly. Clay describes one of his friend’s plans to make a miniature model of the bookstore as “ completely over the top, obsessive, and maybe impossible. Int other words : it’s perfect for this place. ” This is also a description of Sloan’s book. There is a very small shelf of excellent novels in which conspiracy is indistinguishable from reality. Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore deserves a prominent place on it. Right next to The Crying of Lot 49. Sloan’s short novel is richly imagined, playful, and functions like the bookstore: the contents are larger than the container.

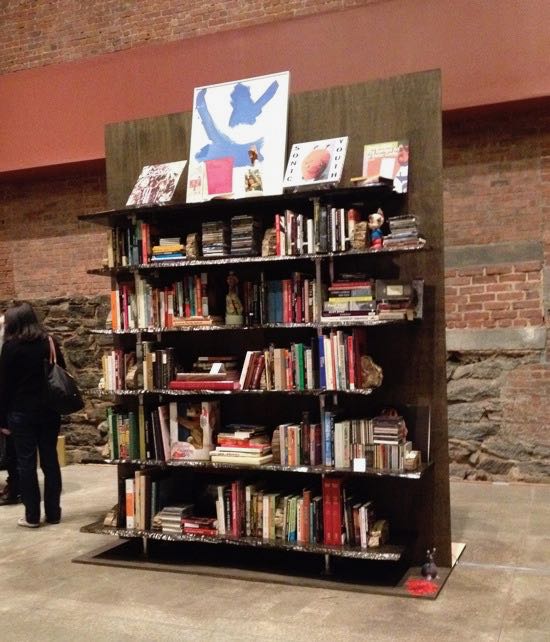

At the New York Art Book Fair

This Mike Kelley memorial installation was an island of calm at the bustling and very cosmopolitan and crowded New York Art Book Fair at MoMA PS1. Anyone who believes the printed book object is on the way out might do well to experience the variety and energy of this event. The Mike Kelley installation was a memorial sponsored by the Gagosian gallery :

— — — —

‘ Some of them are working very hard indeed. [. . .] They are reading ! ’

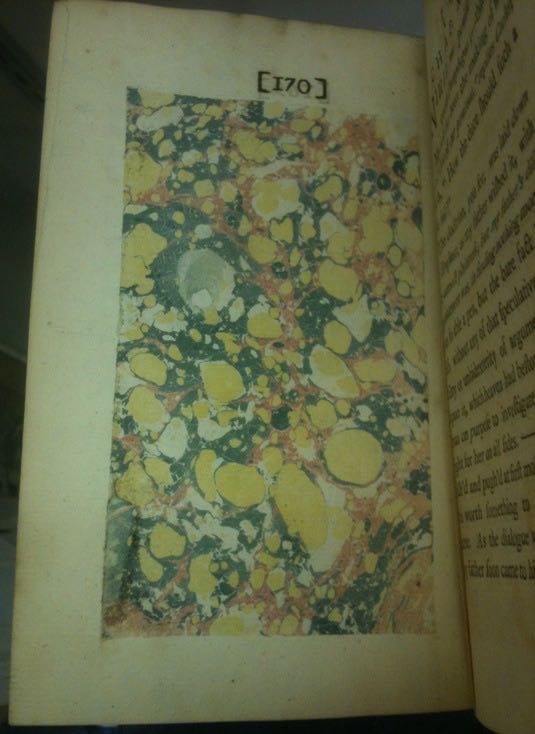

— Louis Lüthi. On the Self-Reflexive Page. [Amsterdam]: Roma, [2010]. [Title from spine]. At the Roma Publications table, I saw this cover from across a crowded room and picked up the last copy of this well-written and wide-roaming essay on unusual pages from Tristram Shandy to the present, illustrated with reproductions of the pages under various headings: black pages, blank pages, drawing pages, photography pages, text (or typographic) pages, number pages, and punctuation pages. Lüthi cites an interesting remark by Jean-François Bory in an anthology of concrete poetry in 1968 :

The writer, thus becoming the layout artist of his book, will no longer write stories (or moments), but books.

and observes that subsequent changes in technology have brought such ambitions into the realm of the possible. This book has no title page, merely two sectional titles. Sterne’s Tristram Shandy is a favorite of the Endless Bookshelf. Here is a picture of the marbled page in the original 1759 printing of the book :

Edinburgh

A recent trip to Scotland, all too short, included a visit to a notable private library, and to the National Library of Scotland, where Temporary Culture donated copies of two titles with Scottish literary connections : Hope-in-the-Mist by Michael Swanwick (about Hope Mirrlees), and My Man and other Critical Fictions by Wendy Walker (which includes The Adamic Language, on the writing of Helen Adam).

The view from a library window

Recent reading :

— Terry Bisson. Any Day Now. A Novel. Overlook, [2012]. A sneaky and beautifully written novel that starts as a collage of small incidents, a memoir of growing up and reading science fiction in the South in the 1950. “ Owensboro was all edges. ” Small raindrops of alterity build to a great river in the 1960s that leads to a strife-torn America utterly unlike our world. The vision of a mid-1960s presidential coup is not dissimilar to the rule of Ferris F. Fremont in Radio Free Albemuth ; Bisson shapes a world that is more historically rooted, true to character, and rich in possibility. Automobile repair, 1960s New York, and a commune in a geodesic dome in the mountains at the Colorado-New Mexico border.

— — — —

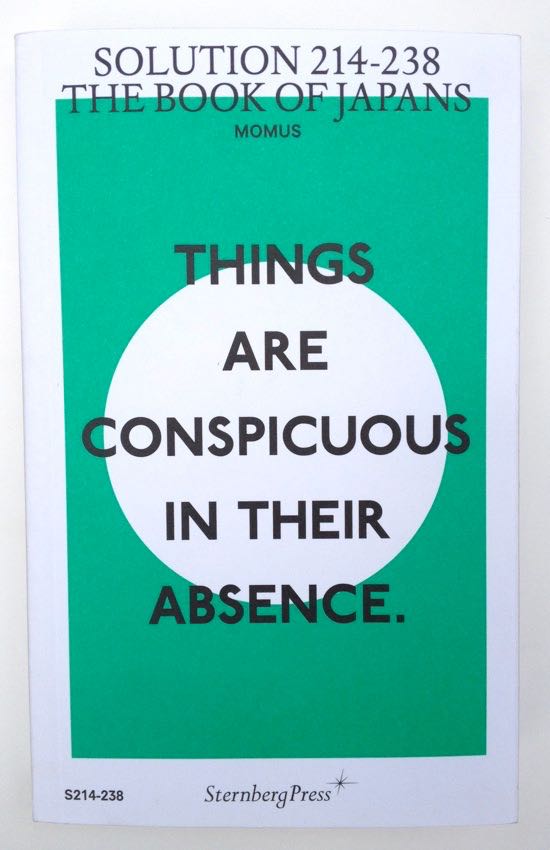

— [Nick Currie] Momus. The Book of Japans. [At head of title:] Solution 214-238. Sternberg Press, [2010]. With a characteristic love of transgressive situations and jokes about incest and bestiality that masks a serious purpose, Momus satirizes Scottishness and Japan-fetishism even as he documents contemporary life and attitudes : playing a notional future against a curious present, this work is closely linked to his Book of Scotlands (2009). He has succeeded in proposing the ultimate gross-out method of time travel.

— — — —

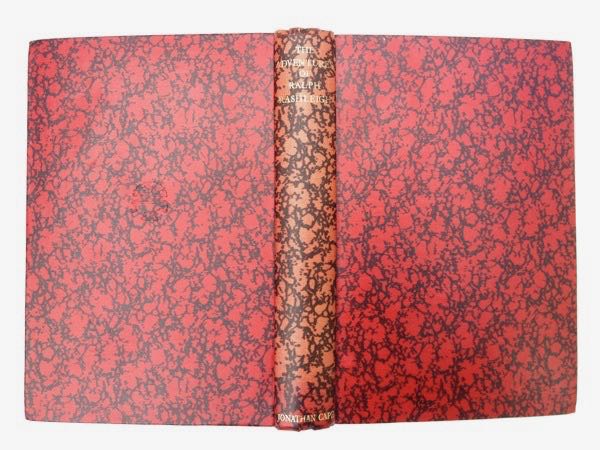

— The Adventures of Ralph Rashleigh. A Penal Exile in Australia. 1825 - 1844. Jonathan Cape, [1929]. Narrative of an early transportee turned squatter. I noticed this book on the shelf because of the unusual cloth binding.

— — — —

— [Charles Warren Adams]. The Notting Hill Mystery. Compiled by Charles Felix (1865). British Library, [2012]. Mike Ashley introduction.

— Barbara Cleverly. The Last Kashmiri Rose (2001). Soho pbk., [2011]. An old crime in Bengal under British rule, with documentary evidence playing a key part ; old photograph albums, a meticulously kept record book for the regimental officers’ mess, and old school copy books. The proportion of narrative time spent describing clothes and photographs in the first half of the book seemed almost a tactic of misdirection.

— Alistair Maclean. South by Java Head. Collins, 1958

— William P. McGivern. Very Cold for May (1950) ; old Penguin pbk. Postwar Chicago hard boiled novel.

— Tom Reiss. The Orientalist. Solving the Mystery of a Strange and Dangerous Life. Random House, [2005]. The complicated life of Lev Nussimbaum aka Essad Bej & Kurban Said, his own most fantastic creation.

— Georges Simenon. The Patience of Maigret. Translated by Geoffrey Sainsbury. George Routledge & Sons, [1939]. A Battle of Nerves (La tÉte d’un homme) ; A Face for a Clue (Le chien jaune).

— Clayton Rawson. No Coffin for the Corpse (1942). International Polygonics, Ltd., [1987]. John Dickon Carr without the deft, light style.

A Familiar Friend

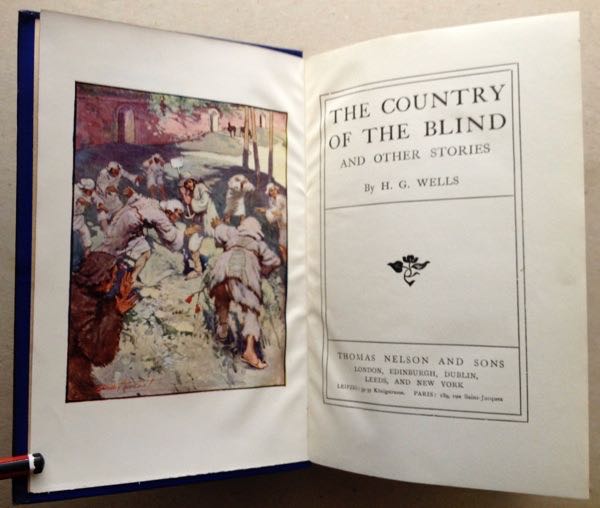

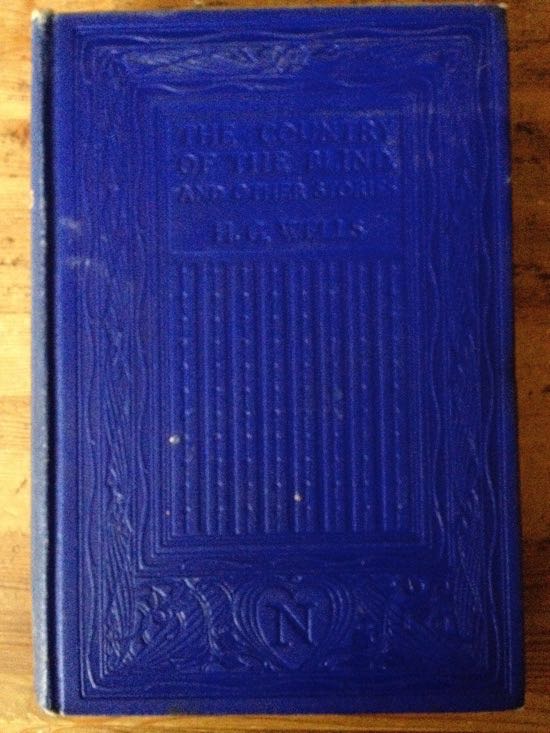

— H. G. Wells. The Country of the Blind and Other Stories. Thomas Nelson and Sons, [1911]. On John Clute’s shelf, I found this old friend, the edition of Wells’ stories that I first read. My copy, picked up at a rummage sale and long ago returned to the elements, was nowhere near so handsome.

Published and distributed earlier this month, a comprehensive and abundantly illustrated catalogue of the Derrydale Press of Eugene V. Connett, 3rd, including books, manuscript material, ephemera, and prints. Details here.

Here and There ; and an Announcement

The Endless Bookshelf will next update on 19 September *, with a review of Robin Sloan᾿s Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore (forthcoming from Farrar Straus and Giroux) and reports of various travels during this week, when your correspondent will be in England and Scotland. I particularly want to see Writing Britain. Wastelands to Wonderlands at the British Library. Pictures and occasional jottings from the road will appear as marginal glosses (at left).

It is with great pleasure that Temporary Culture, the Nutmeg Point District Mail, and the Avram Davidson Society announce the forthcoming release (on 8 May 2013) of a previously unpublished Adventure in Unhistory, The Wailing of the Gaulish Dead by Avram Davidson. More details of the book, to be issued as Publications of the Avram Davidson Society number four, will be available in the November issue of the Nutmeg Point District Mail.

* — in fact on 30 September, with the review to be posted on 1 October

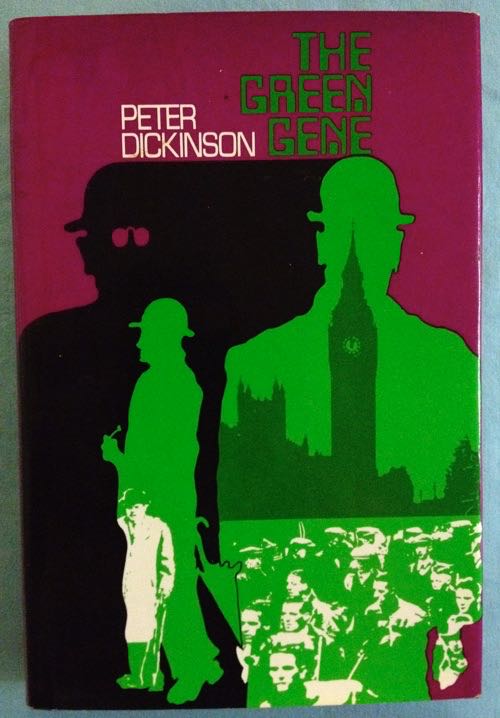

A long shelf of Peter Dickinson

Over the past couple of years I have been reading my way through the novels of Peter Dickinson. This informal project became a sustained adventure when I picked up a shelf of his books last month, and supplemented this reading with what could be found at the library. It is a remarkable body of work, nominally classified as crime fiction, but in fact constituiting an ongoing examination of the decay of English class structures. The late books as deft and unsettling as the early ones. He is particularly skilled at the play of memory — “ For memory is not a single store. ” The Last House Party (1982) — and time in narration, which was why Ellen Kushner suggested Death of a Unicorn (1984) to me in the first place. From Hindsight (1983) : “ How do you distinguish between real memory and invention masquerading as memory ? ” I generally dislike comparisons, but Dickinson’s books have charted a broader social geography than those of Julian Symons, whose Death’s Darkest Face reads almost like a Dickinson novel. Russell Hoban, nothing like him in style or subject matter, is one novelist whose body of work seems of such consistently high quality. I have not read any of Dickinson’s writings for children.

One Dickinson innovation in an early novel has not been recognized as the landmark it represents. The Green Gene (1973), set in an alternate Britain, is a comic satire of Anglo-Celtic relations that masks some brutal truths about English racism. It is indisputably science fiction because of the key roles that genetics, statistics, and computer programming play in the novel. The central character is P. P. Humayan, an Indian mathematician who never forgets a number he has seen and who is given privileged status in a racist society for his skills. He is a medical statistician who has solved the mystery of the Green Gene, the “ genetic accident ” that gave the majority of Celts green skin ; after his abduction by Celtic terrorists, Humayan invents a plan to subvert the reliable performance of the Race Relations Board computer. He instructs a Welsh charwoman (whose studies of mathematics were curtailed when the Celtic Education laws came into effect) in the steps necessary to implement the programming and simultaneously create evidence pointing toward another bureaucrat as the source of the unreliability. The Green Gene is utterly remarkable as an early novel of computer hacking : at a time when there was no language available outside a subset of mathematics to describe computer programming, and in a Britain with only two sophisticated computers (the other at Treasury), Dickinson elaborated a terrorist hacker infiltration plot to disrupt the function and ultimately discredit the racist policies of the establishment. That Humayan must further dissemble and in the end make a deal with the government to emigrate does not undermine the importance of Dickinson’s achievement ; it only anticipates the subornment of hackers by those in power.

— Some Deaths before Dying. Mysterious Press, [1999].

— Play Dead (1991).

— Hindsight (1983).

— The Last House Party. Pantheon, [1982].

— The Lizard in the Cup. Harper and Row, [1972].

— The Yellow Room Conspiracy (1994).

— The Lively Dead. Pantheon, [1975]

— One Foot in the Grave. Pantheon, [1979]

— The Glass Sided Ants’ Nest. Harper and Row, [1968].

— The Green Gene. Pantheon, [1973]

— Sleep and His Brother. Harper and Row, [1971].

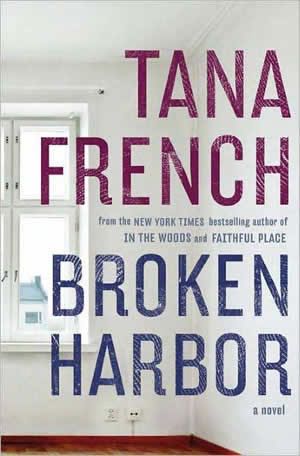

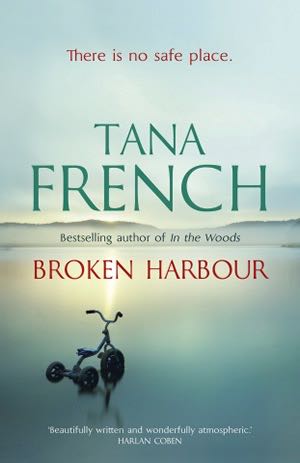

New by Tana French

— Tana French. Broken Harbor. Viking, [2012].

A new novel of the Dublin Murder Squad by Tana French, whose earlier books include the harrowing In the Woods and Faithful Place. Mick Kennedy is called to investigate a vicious crime at a failed residential development, Brianstown, known to the detective from his childhood as the seaside village of Broken Harbor*. The tale of the victims is a tale of middle-class aspirations and of the collapse of the property bubble. French has solved one of the crime fiction novelist’s dilemmas, that of writing the same book again and again, by creating a coherent series that nonetheless demands a new form each time. The first person narrative voices that French has evoked in earlier novels have each been distinct and compelling. Broken Harbor is Mick Kennedy’s relentless voice and the novel is very skilfully paced, dancing right at edge of too much. There are warning signs: “ I watch. I don’t blink ” Kennedy boasts as he attends an autopsy that is charted in grim detail. When he says, “ I keep control.” it suggests that something else is going on as the investigation proceeds. I am impressed with how the solution of the murder mystery is concurrent with the dissolution of the narrator’s orderly life. French is adept at presenting the narrative as self-indictment. Her Dublin is an interesting place to be.

The Endless Bookshelf is pleased to report that Viking, publishers of Broken Harbor, have made available a free copy of the novel to be sent to the first reader who responds to this announcement (U.S. readers only).

* attentive readers will note that the spelling of the place name in the title is anomalous : the title has been copy edited from London edition (Broken Harbour). I am all for following Noah Webster on color and ardor &c. ; but even if Broken Harbour is a metaphor, it is still an Irish place name.

Recent reading

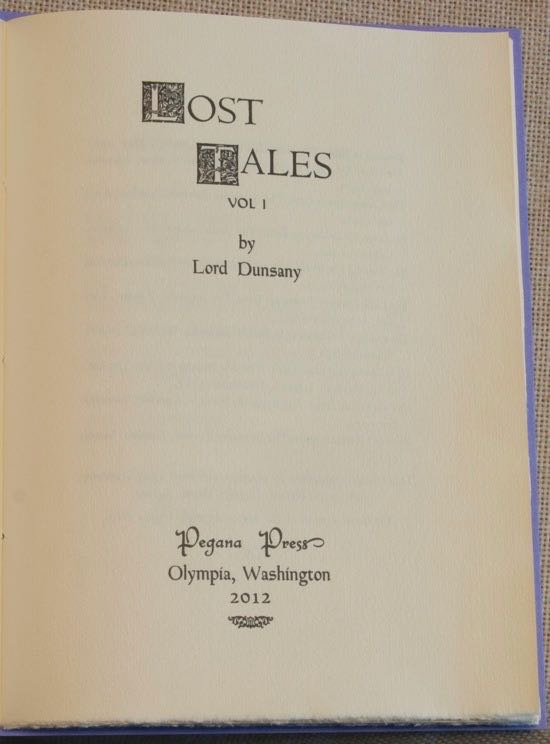

— Lord Dunsany. Lost Tales. Vol I [Introduction by Michael Swanwick]. Pegana Press, 2012. Edition of 128 copies, stitched in lavender wrappers. Previously uncollected Dunsany, from early in his career, assembled in a finely printed edition by Mike Tortorello. “ Romance ” (1909), contains a passage, “ It was like that when I dreamed that I was a fly. ” that strikes direct to the heart of The Strange Journeys of Colonel Polders (1950). A notable and beautiful publication

— Jennifer Egan. A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010). A surprising book, demonstrating total command of story, a fully shaped vision of future present, and the author’s grasp of form : representation of semi-autistic child’s patterning ; and the brilliant final chapter, Pure Language ; all controlled.

— Arthur Machen. The Great God Pan and The Inmost Light. John Lane, 1895. Second edition.

— Bernard Lewis. Music of a Distant Drum. Classical Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Hebrew Poems. Translated and Introduced by . . . . Princeton University Press, [2001].

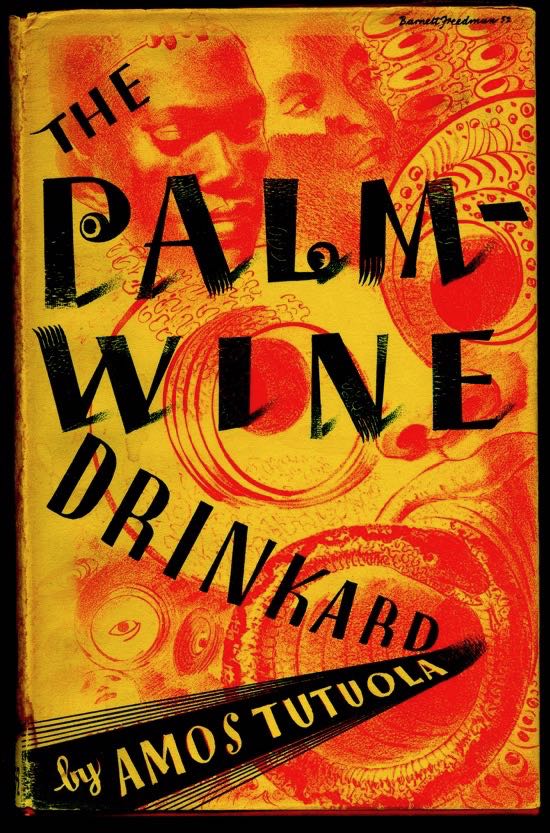

— Amos Tutuola. The Palm-Wine Drinkard and his dead Palm-Wine Tapster in the Deads’ Town. Faber and Faber, [1952]. What an astonishing book ! Every word is the King’s English and yet with those words Tutuola creates another language and another world.

— R.W. Gibson. St. Thomas More: A Preliminary Bibliography of His Works and of Moreana to the Year 1750. With a bibliography of Utopiana compiled by R.W. Gibson and J. Max Patrick. Yale, University Press, 1961.

Lunch at the NYPL

: “ as much food as one’s hand can hold ” — Samuel Johnson

Lunch Hour NYC is the current exhibition at the New York Publc Library (through February 2013).

Commonplace book

Why do I re-read a book ? Because reading is thinking about pattern, walking a path, listening for a quiet voice, shaking ideas together . . .

— — — —

All you had to do was pay attention. People put everything on display, and never knew they were doing it.

— Peter Straub, A Dark Matter

— — — —

Inscription in a copy of The Sword & Sorcery Anthology, edited by David G. Hartwell & Jacob Weisman (Tachyon) :

all historical anthologies are revisionist history — DGH

— — — —

— William Hazlitt, “ Of Persons One Would Wish to Have Seen ” : Charles Lamb “ named Sir Thomas Browne and Fulke Greville as the two worthies whom he should feel the greatest pleasure to encounter on the floor of his apartment in their nightgowns and slippers. [. . .] ‘ There is one person, ’ said a shrill, querulous voice, ‘ I would rather see than all these — Don Quixote ! ’ ”

— — — —

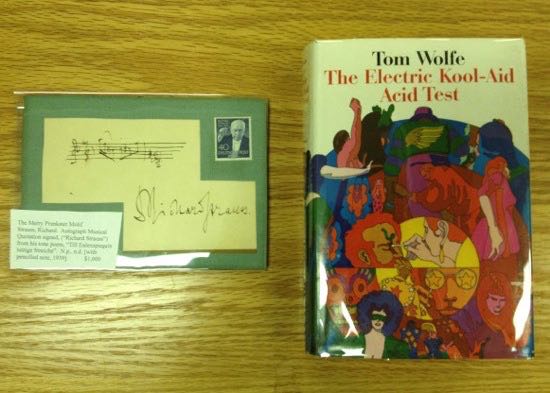

Two Merry Pranksters :

Richard Strauss, Till Eulenspiegel & Tom Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

— — — —

Playing the Right Card :

— — — —

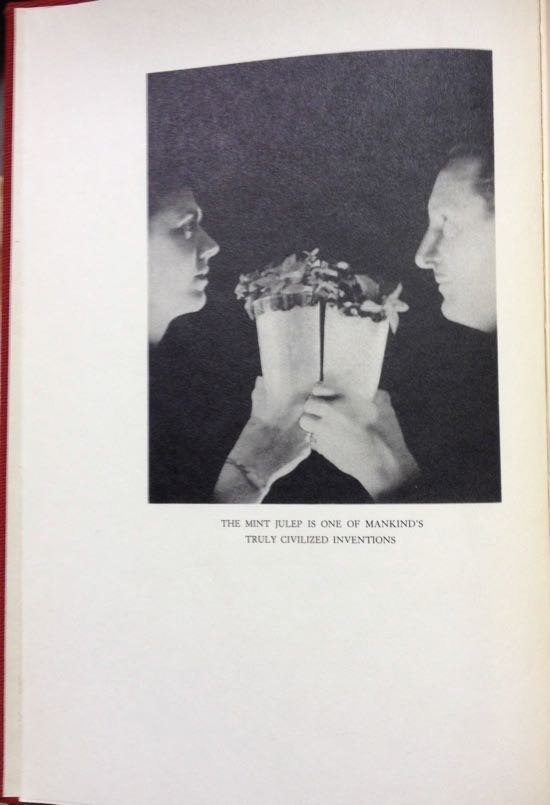

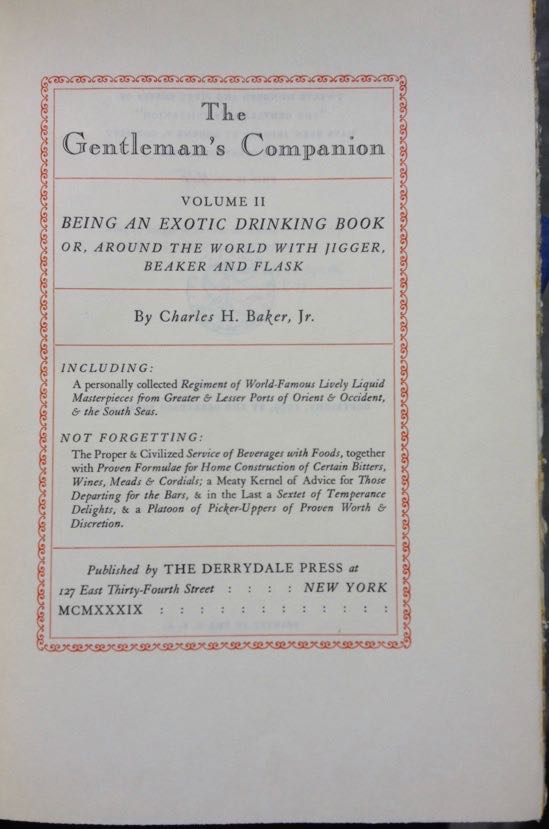

— Charles H. Baker, Jr. The Gentleman’s Companion. Vol. II. The Derrydale Press, 1939

— — — —

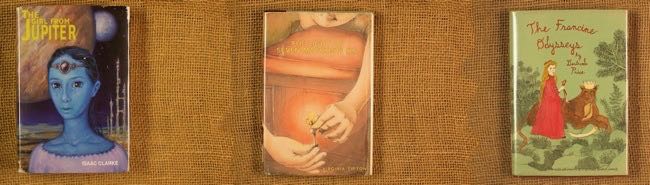

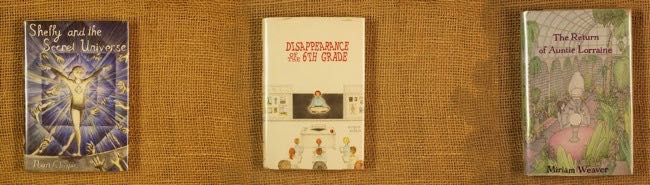

Imaginary books in Moonrise Kingdom :

— Burris & Burris. Disappearance of the 6th Grade

— Nan Chapin. Shelly and the Secret Universe

— Isaac Clarke. The Girl from Jupiter

— Gertrude Price. The Francine Odysseys

— Virginia Tipton. The Light of Seven Matchsticks

— Miriam Weaver. The Return of Auntie Lorraine

— — — —

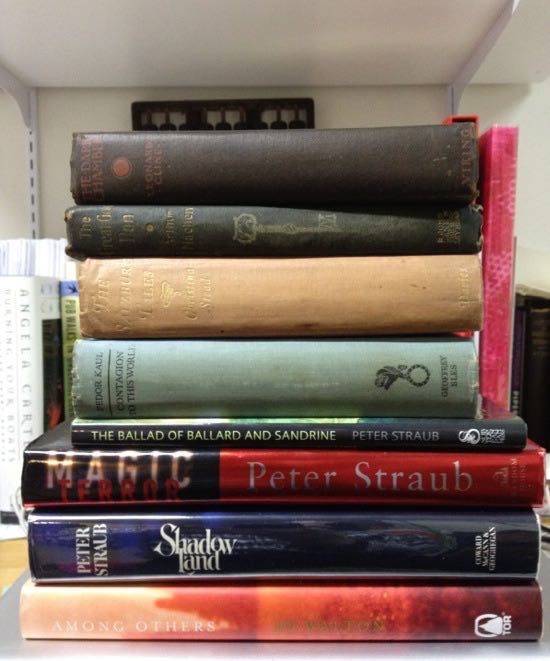

after Readercon : a small stack of books on the desk

This creaking and constantly evolving website of the endless bookshelf : I expect that some entries will be brief, others will take the form of more elaborate essays, and eventually I will become adept at incorporating comments or interactivity. Right now you’ll have to send links to me, dear readers. [HWW]

electronym : wessells

at aol dot com

Copyright © 2007-2012

Henry

Wessells and individual contributors.

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.