October 2010

28 October 10

Current reading :

— Angela Carter. Burning Your Boats. The Collected Short Stories . With an introduction by Salman Rushdie (1995 ; Penguin paperback). Wow ! How have these stories escaped me until now ? All my comparatives are insufficient to express the sharp focus and inventive use of language that are these writings. “ The Cabinet of Edgar Allan Poe ” is an astonishing critical fiction, not unlike the literary vignettes of Guy Davenport but endowed with sharp, savage insight. “ John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore ” conflates the Stuart theater with clichés of the frontier West in the celluloid light of Hollywood Western skies, as complex as anything by Howard Waldrop and then some. A few friends have told me, yes, Angela Carter was already part of the standard English course in the 1990s. That is good news. Everyone should read her.First Words

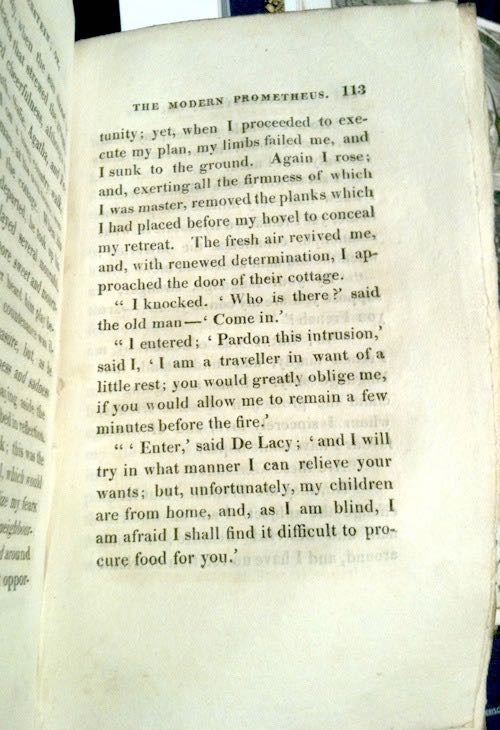

— [Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley]. Frankenstein ; or, The Modern Prometheus (3 vols., 1818). First words, what he really said : “ ‘ Pardon this intrusion, ’ said I, ” occurring at vol. II, p. 113. [Thanks to John Clute who first reminded me of this irresistible passage, which I now turn to in every copy of the first edition of this book that I see. Pardon This Intrusion is the title of his forthcoming collection of essays.]

London and Halifax

This update of the Endless Bookshelf is posted from Camden Town, London, after a long day in the auctions rooms, for the first part of the Sotheby’s sale of the Library of an English Bibliophile. Well attended, with vigorous bidding, few bargains, and a couple moments of irrationality to spice up the event. After testing the pulse of the book world, there are strong signs of life.

On 30 October the Endless Bookshelf will be visiting the Saturday events of the Halifax Ghost Story Festval, and meeting the folks at Tartarus Press. Details at :

http://www.halifax-ghost-story-festival.org.uk/halifaxghosts-saturday.html

Recent reading :

— Peter Dickinson. King & Joker (1976).

— Peter Dickinson. The Last House Party (1982).

— Peter Dickinson. Tefuga (1986).

In everything of his that I have read, Dickinson’s narrative structure

is a deft balance between memory and incident, of events becoming clear

only in retrospection from an irreversible distance of time. The clarity

is sometimes of the dark and unsettling kind, always plainly rooted in

the complex weave of story. King & Joker is hilarious, a

brilliant and carefully observed satire of the depravities of the English

royals ;

clearly, nothing that occurred in the decades following should have been

a surprise to anyone. Dickinson’s choice of a thirteen-year-old

princess is daring, but he carries it off ; and the tributary narratives

feeding the large river of plot are nicely done. The Last House Party is

a novel of the decline of an English country house (territory variously

charted by Julian Symons, Sarah Waters, and Isabel Colegate, and countless

others).

Snailwood speaking in the softened tone he used when trying to give the impression that he was the only man keeping his head in a panicking multitude, but by his physical twitching and quivering producing exactly the opposite effect.

Tefuga, dealing with the colonial past and dysfunctional post-colonial present of a backwater in northern Nigeria (and which I have not yet finished), contains some delicious, brilliant sentences. Dickinson was also an accomplished writer of children’s or young adult novels, to be explored. These three loaned to me by the other [EK].

— Kage Baker, The Anvil of the World (2003 ; Tor paperback, 2010). A very well crafted, layered fantasy novel, rich in portent and a clear sense of ecology, of the complex interrelationships of different orders of beings inhabiting the same world. The tone is as light and sardonic and playful as the Jack Vance interplanetary tales, rich too in plot and image.

‘ language really used by men ’

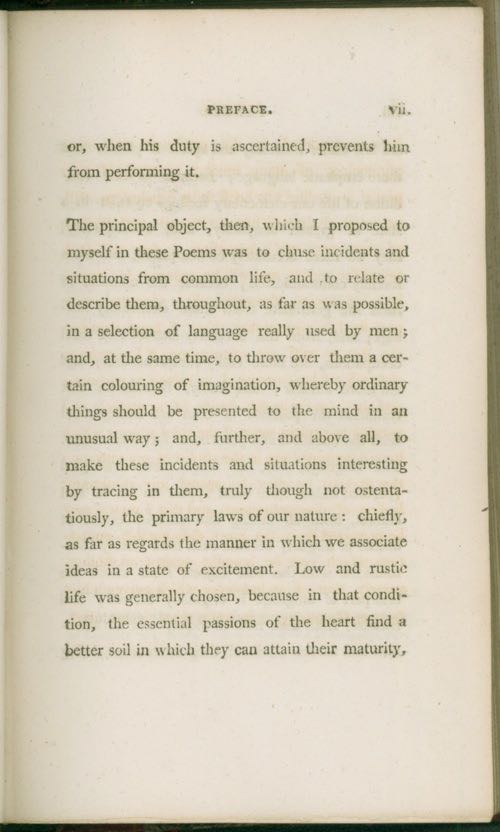

— William Wordsworth [and Samuel Taylor Coleridge]. Lyrical Ballads, with Pastoral and Other Poems . 1802 edition. More details (and pictures) here .

Current reading : Critical Fiction

— Wendy Walker. My Man and Other Critical Fictions . In Manuscript. Six pieces, published in Parnasssus , Conjunctions , etc.

Wendy Walker is author of The Secret Service (1992) and a master of the critical fiction — simply defined as a literary form that adopts techniques of fiction and verse as a critical response to an existing work of literature, “ deploying the language of the text in question ” — and this collection of six critical fictions demonstrates the full range of the form’s potential. Walker moves with equal accomplishment from King Lear to the eighteenth-century autobiography of Olaudah Equiano (Gustavus Vasa) to Joseph Conrad to Harry Mathews. Walker is one of the first to articulate explicitly the form’s capacity to revivify neglected work and — through the inspired choice of “ shards which have variously drawn together and repelled each other ” — to permit the writer to arrive at conclusions impossible to reach through other critical modes.

In the preceding paragraph I have cited some of Walker’s phrases to describe the form. As I number myself among those who write in this form, I propose my own working definition : fiction that works as fiction while simultaneously articulating a critical response to a literary work, and citing phrases and images from the earlier work to new ends ; looking at familiar works in unfamiliar light, to bring out responses and ideas one didn’t know that one didn’t know. I would distinguish the critical fiction, which takes an existing literary work as a point of departure — from the pastiche, which is fundamentally imitative or continuative of the earlier work.

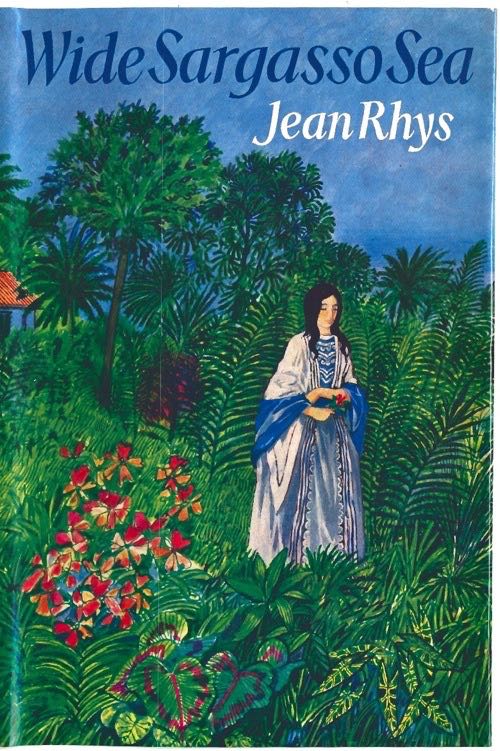

There are notable precursors (I use the word deliberately) for the form : Borges, author of Other Inquisitions and a number of recursive fictions that have an intimate connection to the literary text ; Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea ; Frederick Rolfe’s “ Reviews of Unwritten Books ” ; Joanna Russ, “ The Zanzibar Cat ” and “ The Extraodinary Voyages of Amélie Bertrand ”, two hommages in The Zanzibar Cat ; Walter Abish, 99 : The New Meaning (which interrogates the “ fragmentary narrative ” through the use of appropriated texts). It will be useful to expand this short list with further examples, and to hold a symposium on the topic if there is sufficient interest..

Your correspondent invites comment and discussion on the critical fiction.

‘ forced choice is no choice at all ’

Just received copies this week. I have read the book with great interest and now (Friday) post a short review notice below :

— Douglas Rushkoff. Program or Be Programmed. Ten Commands for a Digital Age . [With original line drawings by Leland Purvis.] OR Books, 2010.

This provocative book is a pamphlet in the best, Thomas Paine Common Sense tradition. It is a concise series of linked essays on the impact of technology on contemporary human life, partly Douglas Rushkoff’s reflections on power and powerlessness, and the question of just what it means to be human in a digital age (unlike any future imagined by Philip K. Dick, whose career seems to have been defined by asking that question, again and again : it is a good question to ask). It is also a prescriptive book, in the sense that Rushkoff articulates his view of just what constitutes an intelligent human being’s response to internet technologies. This will infuriate some readers ; others will find it a clear-headed alternative to the vagueness of a false consensus.

What Rushkoff is advocating in this book is to look beneath the surface, to examine common assumptions about technology in widespread use and thereby “ create the fuel or space we need to wrestle with its implications ”. Worries about the disruptive potential of technology are the other side of the sparkly coin minted by the cheerleaders for the singularity and “ hive economics ”.

They are artefacts of thinking machines that force digital, yes or no, true or false reconciliation of ideas and paradoxes that could formerly be sustained in a less deterministic fashion. Contemplation itself is devalued.

Rushkoff answers the issue of technological overload in the face of the “ perpetual standby ” of the computer and the “ timeless bias of the digital ” with a reminder of what constitutes autonomy : in this case, “ to refuse to be always on. To engage with the digital — to connect to the network — can still be a choice rather than a given. ”

“ While digital technolog[ies] liberated us from our roles as passive spectators of media, their simplifying bias reduced us once again to passive spectators of technology itself. ” Rushkoff makes a clear distinction between “ fractal ” knowledge, gained through glancing at web pages or sampling brief extacts from poetry, music, or art, and “ real knowledge and experience ”. (Both forms have their uses ; but they are distinct in their processes and results.)

In her essay “ SF and Technology as MystiŪcation ”, collected in To Write Like a Woman. Essays in Feminism and Science Fiction (1995), Joanna Russ wrote, “ Hiding greyly behind that sexy rock star, technology, is a much more sinister and powerful Ūgure. [. . .] I think you can see what is being discussed when people say ‘ technology ’. They are politically mystifying a much bigger monster : capitalism in its advanced, industrial phase. [. . .] When intelligent people do it, the mystiŪcation is harder to see. ”

Program or Be Programmed is emphatically not a work of mystification. Rushkoff, whose Life Inc. (2009) is a book length examination of the roots of capitalism and corporate ubiquity, explicitly critiques the model of corporate capitalism in his essay on Tell the Truth, which contrasts the pre- (and post-) capitalist peer-to-peer mechanism for exchange of information and goods that was erased by royal charters for corporate ventures and centralized currencies. And how little has changed, even with the rise of the internet. “ Value is still being extracted from the work — it’s just being taken from a different place in the production cycle, and not passed down to the creators themselves. [. . .] The real problem is that while our digital mediaspace is biased toward a shared cost structure, our currency system is not. We are attempting to operate a twenty-first-century digital economy on a thirteenth-century, printing-press-based operating system. ”

Program or Be Programmed is fundamentally about four ideas : engagement, responsibility, truthfulness, and openness. Rushkoff’s emphasis on genuine contact instead of “ simulations and approximations of human interaction from a distance ” is an inseparable part of each of these notions. Recognition that “ forced choice is no choice at all ” is part of the journey toward informed activity, toward conscious agency and understanding that digital technology is rooted in “a series of decisions ” which we can can learn to control. The current bias toward commodification, centralization, and abstraction is the result of choices in programming ; the march in simulation is not inevitable or irreversible. “ What the postmodernists mayhave underestimated, however, was the degree to which the tools through which these symbolic worlds are created — and ways in which they might be applied — would remain accessible to all of us. ” There is a good measure of common sense throughout Program or Be Programmed , and the book is rich in sentences that might become apothegms, yet they are rooted in Rushkoff’s arguments and fully ripened.

“ But not everything is a datapoint. ”

“ Content was never king, contact is. ”

Each of Rushkoff’s ten “ commands ” discusses a real issue of concern. The echo of the Mosaic tradition is a conscious choice on his part, since the essays chart a long arc from restricted access to knowledge to non-hierarchical, unmediated access to knowledge, information, and communication. If the number ten bothers you, add another one (or three), such as Go outside. Shut the door (as in Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies ). Or : “ Solvitur ambulando ”. Or, as the Endless Bookshelf advocates, Go for a walk in the woods. In this instance I suspect Rushkoff might concur when I add, just remember to leave the device behind, or let the battery go dead.

Signing off, for now. [HWW]

Recent reading :

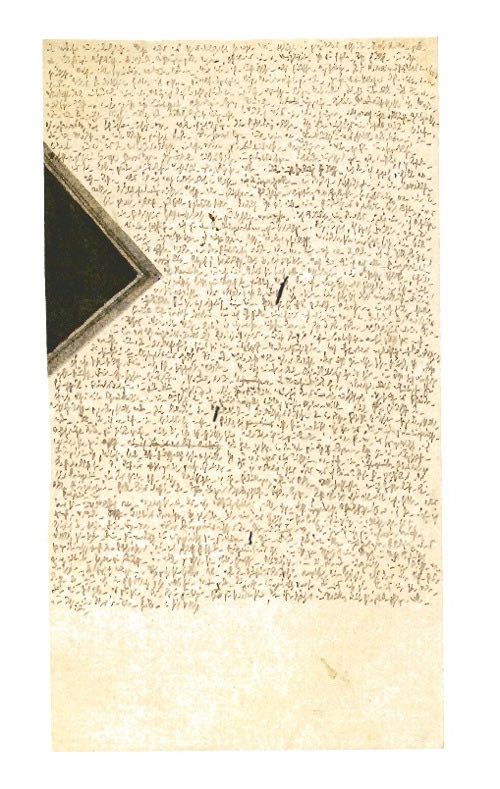

— Robert Walser. Microscripts . Translated from the German and with an Introduction by Susan Bernofsky. Afterword by Walter Benjamin (New Directions/Christine Burgin, 2010). A selection of Walser’s hermetic writings, each text illustrated at full size, ith a fascinating introduction, “ Secrets, Not Code ” that gives a sense of how these manuscript fragments survived — Walser was confined in an asylum for the last twenty-three years of his life — and were eventually deciphered. The German originals are included. A beautifully produced volume, the book is quite alarming, too, for the microscripts are documentary evidence of the private (non-communicative) aspects of writing : they remained opaque for more than thirty years after Walser’s death.

— Charlotte Jay. Beat Not the Bones (1952 ; Soho paperback, [ca. 1995]). Mystery, seeking the truth at all costs; set in New Guinea, and the truth is as monstrous as anything since Heart of Darkness .

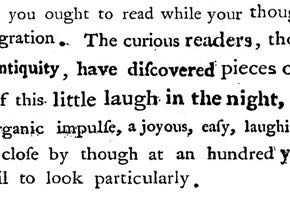

— Tom La Farge. Life and Conversation of Animals . Proteotypes, 2010. LIBELLULÆ 1. Visual verbal fun, “ gregarious words ” and “ fresh language falling ” from Selborne into now, a typographical cut-up of Gilbert White’s observations of The Natural History of Selborne with La Farge’s deft, playful attention to language.

I cannot reproduce the lovely late eighteenth-century letterforms (including the long s), but these lines give a little of the flavor :

the congregating of hordes of incongruous animals of language,

tribes distinguished by an appellative matted all over with cobweb,the flakes of this perfect language hung in the trees and hedges so thick,

that a diligent person might have gathered the power of mounting [. . .]

the regions where loco-motive Letters are formed, air faster than the air itself.

La Farge is walking along the littoral of sense and meaning, and it is pleasant and challenging to walk there with him.The LIBELLULÆ device, a finely inked dragonfly, is beautiful.

Wander in the Archives

The Archives of the Endless Bookshelf have been swept and tidied and a guide has been prepared to assist wanderers. Index would be too strong a term : the headwords tend to be suggestive rather than directive. Start here. Have fun.

This creaking and constantly evolving website of the endless bookshelf : I expect that some entries will be brief, others will take the form of more elaborate essays, and eventually I will become adept at incorporating comments or interactivity. Right now you’ll have to send links to me, dear readers. [HWW]

electronym : wessells

at aol dot com

Copyright © 2007-2010

Henry

Wessells and individual contributors.

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.