September & October 2009

29 October 09

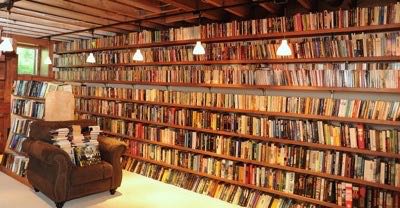

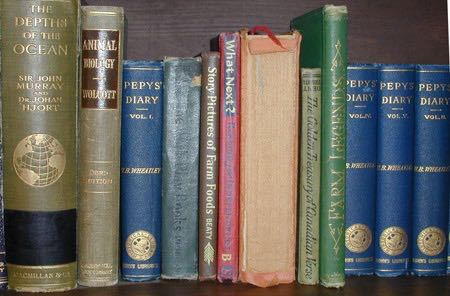

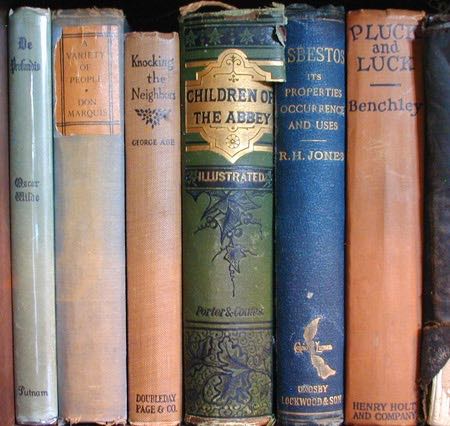

Bookshelves at work : an occasional series

Courtesy of [AB]

28 October 09

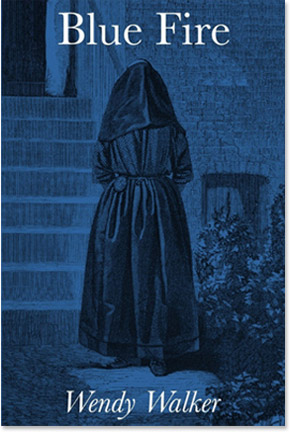

Blue Fire by Wendy Walker

— Wendy Walker. Blue Fire. A Poetic Nonfiction [Proteotypes, 2009]. xvi, 253 pp. Illustrated.

This is the first published edition of a work that I have followed over the years as Wendy Walker, author of The Secret Service (1992) and the most perceptive practitioner of the critical fiction mode working today, researched the life of Constance Kent and the Road Hill House Murder of 1860, evolved the intrepretive mode, and brought the project to fruition. I have one of a very few copies of Blue Fire : Confessing Constance Kent (May 2001; not published), an earlier form and format of the book. I am too closely linked to the author and the project to review the book, so the following is a brief critical commentary.

What is remarkable about Blue Fire. A Poetic Nonfiction is Wendy Walker’s insistence upon working with the literary materials and facts of Constance Kent’s life in an ethical manner and in creating the broadest possible context. “ The Great Crime of 1860 ” was sensational in its day and was important, too, for certain legal precedents, so the sensation has never entirely dissipated. Recent accounts of the crime have seemed of too narrow compass. It is an appalling situation that a young woman could be sentenced to death upon the basis of a false confession that conflicted with facts established during the earlier, inconclusive hearing. And the ultimate silence of Constance Kent, during her imprisonment and after her release, raises other issues. The power of Walker’s approach is rooted in recognition that to render it in fiction would be unethical appropriation.

Because so much historical fiction plays irresponsibly with the past, and because so much history and biography leaves its sources unacknowledged, I wish to be as transparent as possible about my method in Blue Fire .

The reasoned delivery of information is one aspect of clarity. Most of the introduction to the published edition is found in the earlier version. The triumph of Blue Fire is in making visible — and tangible — that Walker has employed, together with a subtle re-ordering of the movement from exposition of background to implementation of process.

As I studied the mosaics that Constance Kent had made, a mosaic method of composition came to seem apposite. The specific way of combining texts that could be described as mosaic was inspired by my reading of Paul Metcalf, who created text in poetic non-fiction by a careful splicing of significant passages drawn from other writers. So I set the issue of genre aside and began to collect such shining passages.

Walker’s introduction now includes an example of the process by which she derived the poetic text and the passages in justaposition. I like to see the traces of the scaffolding by which a text is shaped. Blue Fire presents a poetic text that makes use of white space to emphasize drama and deliberation. This occupies the left hand pages ; the right hand pages are the gloss upon this text, passages from Walker’s source material that are inseparable from the poetic text and at the same time information of a different order. The range of Walker’s reading is the rock solid structure in and on and about which the poetic text dances : in particular, her close study of the literary and scientific works forming the contemporary climate of 1860. The result is kinetic and enables the reader to “ catch Constance in the spaces between speech, her own and others’. ”

24-25 October 09

The Function of Celtic Humor

Part 2 : Up The Forking Garden Paths

— [Nick Currie]. The Book of Scotlands . Momus. [At

head of title :] Solution 11-167. Series Edited by Ingo Niermann. (Berlin :

Sternberg Press, [2009]).

Since the mid eighteenth century Scotland has been an imaginary country as

well as a geography : with collective memories of the Forty-Five still

fresh, James Macpherson’s Fingal (1762) — allegedly

translated from epic verses composed by a blind poet of the third century

named Ossian — provoked throughout Europe a fascination with

the savage inhabitants and primitive landscape of Scotland. In the end,

it hardly mattered that Macpherson’s source was invented : the

divergence between actual and notional was irrevocable. And surely the

idea of Scotland that appealed to Goethe was distinct from Macpherson’s

concepts of the country, or Samuel Johnson’s. Burns, earthy and funny

in his verse, lived and died in Scotland ; is it the same land that

his readers visit or inhabit ? By the time of Stevenson, madness and

doppelgängers marched hand in hand with Highland mercenaries and the

ghosts of evicted crofters. And from Stevenson to Borges is a single step

within the dream of literature.

The Book of Scotlands by Nick Currie (“ Momus ”) is a formally constrained philosophical exercise, a discontinuous accumulation of alternate political and social histories of Scotland in varying literary modes. Comprising some hundred and sixty numbered, nonsequential passages — ranging from a single, gnomic sentence to involved sketches several pages in length — The Book of Scotlands is hilarious and insightful and even moving on occasion. Currie plays on all manner of conventions and expectations, in Scottish history and literature as in form and tone ; and reverses, subverts, and surprises : as if somehow Borges were the author of Mao’s Little Red Book.

SCOTLAND 122

The Scotland in which Lord Summerisle’s human sacrifice does indeed bring a full and florid harvest the following year.

* * *

SCOTLAND 14

The Scotland in which Irn Bru really is brewed from “ iron girders ”.

* * *

One of the darkest, funniest passages is Scotland 116, the “ Employee’s Guide to the Scots ”, which moves Harry Mathews-like from bland to outrageous. There is also a thread of nostalgia and exile, usually buried, but sometimes rising to the surface, and sometimes transmuted into gold : within the compass of three pages, Scotland 154 of the refugees, the tone moves from paranoia — “ Because we were Scots. Filth, in their eyes. . . . If we were in Wales, we were lost. ” — to an eerie solidarity : “ We owe everythng to our comrades, the Welsh. They saved our lives. If they rule Scotland now they deserve nothing less. ” For Currie as for Joyce : silence, exile, and cunning : distance is no obstacle to addressing the idea(s) of Scotland, perhaps distance is requisite to find the necessary perspectives.

The Book of Scotlands is closely tied to The Book of Jokes (discussed in the first part of this essay, here), not only because Scotland 28 and Scotland 119 appear verbatim in The Book of Jokes , but also because there is plenty of humor about the body and sex and food. The jokes work, here, for the most part : the tone is lighter — playful even though serous — and there seems to be less hostility toward the reader. The Book of Scotlands is recognizably science fiction, a work of utopian literature in its vision of Scotlands, with futures at near and far term, at least one instance of time-travel (or time lost in Faerie), and direct allusions to Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles and to Nineteen Eighty-Four (elsewhere, discussing the “ rather amoral slogan ” used on the cover, Momus has written, “ the Orwell novel is a sustained parallel England in the same way my texts are sustained parallel Scotlands ”). In one of these futures, Currie gives his ambition free reign : “ The Scotland which, exactly ten years after publication of my Book of Scotlands , sweeps me to power, Velvet Revolution style. ”

SCOTLAND 50

The Scotland in which you can see ghosts at noon, clear as day.

* * *

The Book of Scotlands is a seed that plants itself in the reader’s awareness. The entries succeed each other, dialect Scotland and Soviet Scotland and Scotland as divided Berlin and capitalist playground Scotland and Scotland as Japan and . . . and then that rare thing occurs : the reader is suddenly able to entertain the multiply contradictory elements all at once, and all the Scotlands are simultaneously co-emergent, only to be extinguished in the savage satire of the final passage Scotland 158, the “ healthy eating drive ”.

Categories, and Bats

Fred Lerner, author of The Story of Libraries. From the Invention of

Writing to the Computer Age (Continuum, 1998; 2nd ed., forthcoming,

2009) and chief of the PILOTS Database (Electronic Index to the Traumatic

Stress Literature) produced by the National Center for PTSD, is also author

of a long-running ’zine, Lofgeornost , which is read

immediately upon receipt, with pleasure and interest. Two brief passages

serve to demonstrate the range of subjects.

In Lofgeornost #90, reporting correspondence from Dainis Bisenieks,

who writes : “ Unlike real libraries, this accumulation

is uncatalogued. I know what I have. [. . .] I have

mentioned the classification into ‘ Memory, Reason, and Imagination ’ (Bacon,

1605), but there are such spinoffs as separate shelves for Chesterton and

for Cabell, or small-format books in Latvian. ” Lerner comments, “ My

spinoff shelves cover books about science fiction ; classical and mediaeval

literature ; Judaica ; Rudyard Kipling ; and John Myers Myers. ” Elsewhere

Lerner writes of searching in that portion of his library stored in boxes. “ My

serendipitous finds are often more interesting than the books I was originally

looking for. ”

And from Lofgeornost #88 :

But to someone who has spent a couple of decades acquiring a nodding acquaintance with history’s great libraries — and whose career has been spent more with electrons than with books — a visit to the Biblioteca Joanina [Coimbra, Portugal] was something in the way of a pilgrimage.

And I managed to learn about one aspect of practical librarianship that I had not previously encountered. The elegant wooden tables are covered with drop cloths every night, the keeper told me, to protect them while the insect control system — a colony of resident bats — makes its nocturnal rounds.

— Gene Wolfe. Pirate Freedom (Tor, [2007]). A beautifully written time-travel hommage to Treasure Island and Esquemeling and the rich literature of piracy and adventure : implausibility rooted in the gritty reality at the turn of the eighteenth century. “ We are the people of your past. ”. The single other narrative employing the formal device (a time-travelling priest) that springs to mind is Tom Disch’s dark and gleeful horror polemic The Priest. A Gothic Romance (1994), beside which Wolfe’s novel is a bright murderous sunny day.

— Joanna Russ. The Adventures of Alyx (Timescape, [1983], paperback). This collection contains a handful of stories published by Damon Knight in the Orbit anthologies and the short novel Picnic on Paradise (1968). It is the fictional manifestation of the mirror of critical thinking that Russ held up to the field of fantastical literature : a resourceful, autonomous woman protagonist climbing into the tropes of high fantasy or alien planet science fiction.

— Joanna Russ. We Who Are About To . . . (Dell paperback, [1977]). Acerbic, poetic, and relentless novel, a chemical retort in which the scenario of cheery survival on an alien planet is fractured and distilled into something fresh and dangerous. I read this two days ago, and in today’s mail I found The New York Review of Science Fiction for October, with a fascinating essay by Darrell Schweitzer on Randall Garrett’s story “ The Queen Bee ” (1958), which offers some additional historical context : “ Did Joanna Russ write We Who Are About To . . . in white-hot rage in response to this specific story ? Certainly she read the magazine science fiction of theis period as a youg woman. Her book is quite obviously an angry demolition, if not of this story, of the widespread clichés and assumptions behind it. Why is it necessary to populate one more chunk of rock with humans . . . ? ”

23 October 09

Blue Fire by Wendy Walker

Just received an advance copy of Blue Fire. A Poetic Nonfiction [Proteotypes, 2009], Wendy Walker’s book on the story of Constance Kent and her false confession to the Road Hill House murder, the “ Great Crime of 1860 ”. Blue Fire is a formally innovative and beautifully composed work of poetic non-fiction. “ Since she left no explanation, I decided to try to capture her logic in the grammar of silence. I have attempted to catch Constance in the spaces between speech, her own and others’. ” There is a party to celebrate its publication (and publication of Homomorphic Converters , the second in Tom La Farge’s series 13 Writhing Machines), tomorrow, 24 October, at Proteus Gowanus, 543 Union Street, Brooklyn, New York, NY 11215 (T. 718.243.1572).

“ I myself . . . would rather be told too little than too much. ”

— Marianne Moore

A real work of art

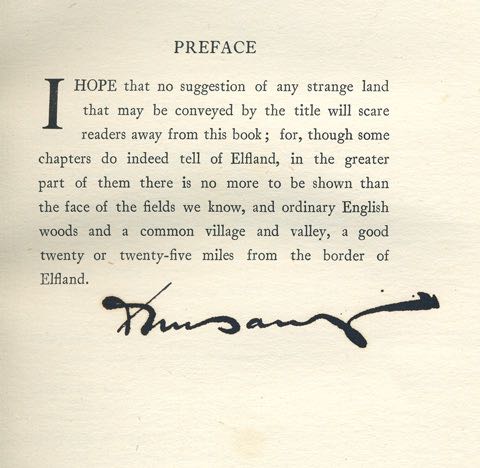

— Lord Dunsany. The King of Elfland’s Daughter . London : G. P. Putnam’s Sons, [May, 1924]. First edition, 250 copies, signed by the author, with a frontispiece by Sidney H. Sime, signed by the artist. Quarter vellum and terracotta cloth, printed dust jacket.

This is one of the most beautiful books I know, both as artefact and as a profound exploration of loss. The marvel for me is in Dunsany’s invocation of the wonder of the rural countryside — “ the fields we know ” — and his ability to describe absence as a kinetic process.

And now the King and his daughter drifted away, as the smoke of the nomads drifts over Sahara away from their camel’s-hair tents, as dreams drift away at dawn, as clouds over the sunset ; and like the wind with the wind with the smoke, night with the dreams, warmth with the sunset, all Elfland drifted with them. All Elfland drifted with them and left the desolate plain, the dreary deserted region, the unenchanted land. (127)

The barren lands over which Alveric wanders in search of Elfland are the trenches of the Great War extending into once familiar fields.

In an essay in The New York Review of Science Fiction for January 2000, Darrell Schweitzer describes how Dunsany has written “ the perfect fantasy sentence , which deserves recognition alongside such perfect science-fictional phrases as Heinlein’s ‘ the door dilated. ’ ” Here is the sentence :

But when Alveric with his sword was far to the North the Elf King loosened his grip with which he had withdrawn Elfland, as the moon that withdraws the tide lets it flow back again, and Elfland came racing back as the tide over flat sands. (149)

This is an old-fashioned book, and a real work of art : in Dunsany’s sonorous prose the unattainable is made visible for a moment.

Wander in the Archives

The Archives of the Endless Bookshelf have been swept and tidied and a guide has been prepared to assist wanderers. Index would be too strong a term : the headwords tend to be suggestive rather than directive. Start here. Have fun.

Your correspondent is at work on a couple of writing projects and this preoccupation will likely diminish the frequency with which the Endless Bookshelf is updated during the next two months. Pictures of bookshelves and communications from readers will be posted immediately.

16-17 October 09

Current Reading

— Gene Wolfe. The Best of Gene Wolfe. A Definitive Retrospective

of His Best Short Fiction (Tor, 2009). Marvelling at the concision

and control of the means and timing and beauty with which information is unleashed,

particularly in “ The Death of Dr. Island ” (1973) :

[. . .] as though Nicholas had plunged his face into a dream. Far, far below him Jupiter displayed its broad, striped disk, marred with the spreading Bright Spot where man-made silicone enzymes had stripped the hydrogen from methane for kindled fusion : a cancer and a burning infant sun. Between that sun and his eyes lay invisible a hundred thousand kilometers of space [. . .] (150)

Evoking an advanced technology in a passage that is at once an essential clarification of how the island works (integral to the story) and a beautiful throw-away. Another thing I have noticed again : how sinister Wolfe’s use of the second person singular narration in “ The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories ”. And what about the first person narratives ? The five pages of “ Game in the Pope’s Head ” are among the densest, most allusive and layered in the book, yet also impish and quick. It is interesting to note several explicit acknowledgments to Chesterton in Wolfe’s afterwords.

— Neil Gaiman. American Gods. A Novel (William

Morrow, [2001]). Dark and playful love letter to America, with complex

folkloric and literary resonances (My favorite, somewhere in Missouri,

at the center of America, when “ Someone knocked on a door,

called ‘ Hurry up please, it’s time, ’ and

they began to shuffle in, head lowered. ” Would that someone

be the shade of old Tom, p’raps ?). Another book that prompts

me to say, I do not know how this one slipped past me until now.

— Isabel Colegate. The Shooting Party (1980 ;

Penguin Books paperback, [1982]). A vanished world of rural privilege that knows

itself to be vanishing (a little too much so). My recollection of the tenor of The

Good Soldier (1915) by Ford Madox Ford is that disbelief prevailed :

how could it all have ended ? In The Shooting Party , the

encounter between the baronet, Sir Randolph Nettleby, and the radical pamphleteer,

Cornelius Cardew, is choice, hilarious.

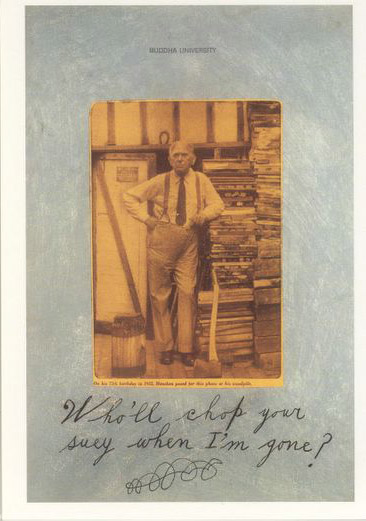

Thousands of Books on Melrose

Thousands of Books on Melrose by Will Etling

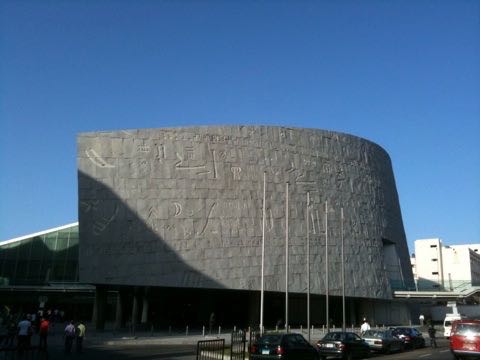

Bibliotheca Alexandrina

The new library of Alexandria, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Picture by Endless Bookshelf correspondent [SM].

13 October 09

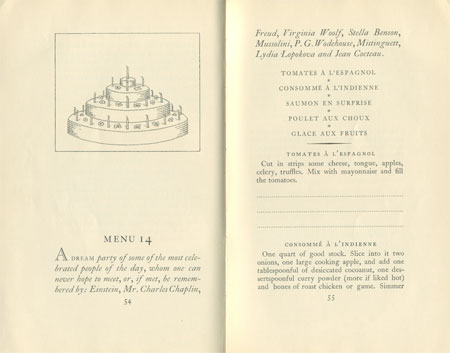

The Future of the Cookbook

page detail from : Ruth Lowinsky. Lovely Food. A Cookery Notebook. With Table Decorations invented & drawn by Thomas Lowinsky . London : The Nonesuch Press, 1931

The Future of the Cookbook is the charming and interesting and deftly illustrated project of Kim Beeman, librarian of the French Culinary Institute in New York.

11 October 09

Karli Frigge

Marmerpapier met “ golfslag ”-patroon

in rood, geel en zwart

Karli Frigge. 210 x 195 mm. Codex Purpurus, dl. IX: De Pauwstaartmarmers,

1992. PC SIEMA FR107

(from the 100

highpoints exhibition at the Dutch National Library)

happiness always interrupted

him

Improving the perfection of a phrase divulged by Boswell, Hudson says that

many times in his life he undertook the study of metaphysics, but happiness

always interrupted him. That sentence (one of the most memorable I have encountered

in literature) is typical of the man and the book. In spite of the bloodshed

and the separations, The Purple Land is one of the very few

happy books in the world. [. . .] I am thinking of the happy disposition

of Richard Lamb, of the hospitality with which he welcomed every vicissitude

of life, whether bitter or sweet.

Borges, “ About The Purple Land ”, Other Inquisitions

9 October 09

Current Reading

— Peter Holliday. Edward Johnston.

Master Calligrapher (The British Library & Oak Knoll

Press, 2007). xx, 389 pp. Detailed and wide-ranging study of Johnston,

his life’s work, and his enduring influence upon the world

of letters. Complements Priscilla Johnston’s matchless, lovely

biography of her father, noted here.

— H. F. Wood. The Passenger from Scotland Yard. A Victorian Detective

Novel . With a new introduction by E. F. Bleiler (1888 ; Dover

Publications, [1977]).

— Bernard Lewis. The Assassins. A Radical Sect in Islam (1967 ;

Weidenfeld & Nicholson, [2001]). Re-reading a work familiar to me from my

student days. “ And of all the lessons to be learnt from the Assassins,

perhaps the most important is their final and total failure ” (from

the preface to the new edition, written January 2001).

— Diana Wynne Jones. Howl’s Moving Castle (1986 ;

Greenwillow, 2001). [Re-read].

Alycia Martin

A book review is neither endorsement

nor product placement. A book review, a written essay about a written

work, is a literary response to the intellectual content and context

of a book. It is a phrase in an ongoing literary conversation.

In the first post of the Endless

Bookshelf, I wrote :

I see that I have just made a decision that may run contrary to all currents in blogging — to link to author and small press and individual websites, but not to big corporate sales sites. I presume that anyone reading can choose how to obtain current commercially published books, or not. We’ll see.

Sometimes the Endless Bookshelf functions as a forum for extended reviews or essays ; at other times, it functions simply as an ongoing digital commonplace book with occasional excerpts of noteworthy passages.

But the dust and smoke and noise of modern literature have nothing in common with the pure, silent air of immortality.

— William Hazlitt, “ On Reading Old Books ”

30 September 09

Commonplace Book

“ The idea of beginnings or incompleteness is the ideal state of art. ”

— Ernst G. Benkert. 623 Titles without Paintings and 8 drawings without titles. Quotations, Annotations, Notes 1961-2008 [Proteotypes, 2009]. An interesting expansion of the meaning and function of the artist’s commonplace book. Benkert writes, “ . . . giving the quotation a title was always in itself a form of commentary. My quotation and title making gave me a kind of pleasure not available to me in painting, so that what started as casual note-taking began in time to rival my work as a painter. I sometimes felt guilty about this, but eventually realized that my quotation collecting was an essential complement to my art. ” The arrangement of these quotations invites collisions of time and biography and meaning ; and Benkert’s commentary is at times playful, at times serious (and it may be difficult to untwine those two modes). Some selections follow :

NO FUTURE

(Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian, and perhaps even Pollock worked for posterity.) — EGB (1980)

(Today the word ‘ posterity ’ carries no meaning, but artists still work as though it did.) — EGB (2008)ANOTHER DEAD PAINTING

NAMELESS

“ To see is to forget the name of the thing one sees. ” — Paul Valéry

(All who lecture on art should be mindful of this.) — EGB (2007)NOT EXACTLY

“ L’exactitude n’est pas la vérité. ” — Matisse

Data storage and retrieval

From the Davies Project : Research into the History of Libraries in the United States, ALB1876 : Database of American Libraries before 1876 (Princeton University). How the data was stored by its compiler, Haynes McMullen :

“ On ne le répétera jamais

assez : sans un index, un livre est inutilisable aux yeux d’un

chercheur. ” (It can never be repeated enough : without

an index a book is useless in the eyes of a seeker.) — Pierre

Assouline, La

république des livres

Image : La machine a écrire de Léo Malet sur son bureau

même, Médiathèque de Montpellier, 2009 (2048 x 1536 image )

29 September 09

— Roland Chambers. The Last Englishman. The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (Faber and Faber, 2009). New light on the author of the Swallows & Amazons books and the years of his life spent in and around the Russian Revolution. One always knew, somehow, that Captain Flint had been playing for high stakes before he settled into that houseboat to write his memoirs.

Arthur Ransome, literary bohemian turned journalist, escaped the straitjacket of his unhappy first marriage through travel to Russia just prior to the start of the war in 1914 ; he met everyone, and visited Russia repeatedly as foreign correspndent for English papers ; Lenin called him a “ useful idiot ” ; Ransome fell in love with Trotsky’s private secretary, played chess with revolutionaries and White Russians, ferried money to Sweden for the Bolsheviks, acted as unofficial diplomat, and was recruited as agent of MI6. And then, when the opportunity presented itself, he sailed from the east Baltic in his yacht Racundra and resumed the writing life in England. A fascinating subject, lots of new data released from British archives, and quite mind-boggling to envision the Swallows and Amazons on the revolutionary barricades : the Walker children play mumblety peg with Rasputin and the Coot Club hoists the red flag to sail the Volga during the Russian famines.

The journey is not without its trials and difficulties : especially in the years 1917-1918, the narrative time frame is ambiguous and tangled. What is going on in a given paragraph is usually clearly present ; it is the when of specific events that sometimes appears jumbled. Chambers is fond of adducing as causes what seem in fact to be effects, and also makes heavy use of the tortured chonological aside. It is, finally, not relevant at all that Hitler’s armies were besieging Stalingrad at the same time that Ransome’s wife Evgenia wrote a succinct critique of The Picts and the Martyrs , then still in manuscript. Most maddening of all, there are NO ENDNOTES.

In his review of the biography published in the TLS , Julian Evans seems to assert that Ransome enriched himself though his Soviet contacts and the millions of roubles in diamonds he brought out for overseas propaganda. I don’t read the sequence of events that way : first, it seems that Ransome was simply too sincere to have done such a thing (and probably too closely watched by the Soviets) ; second, any such wealth would have figured in the divorce settlement that freed him to marry Evgenia Shelepina ; and finally, while he and Evgenia endured privations to build Racundra , Ransome eventually sold the yacht for 200 guineas, hardly a tyrant’s horde.

The Last Englishman is a quirky biography, with a style that is sometimes irritating or obscuring, but Chambers adds so much to the rather sanitized version of Ransome’s life that it will become essential reading. A bad decision somewhere that led to the lack of notes, in effect the omission of the really interesting part : how and where Chambers learned what he records.

Taxonomy of the Book Trade

— Edward Maggs. “ Only the Brave Deserve the Fair :

An Inquiry into the Ecology of the Modern Book Fair ” in : Gazette

of the Grolier Club. New Series 54 (2003), pp. 88-96. A fine and truthful

whimsy, in one section of which Maggs describes the following types of book dealers,

with specific reference to book fair booths or stands : The Barker, The

Knitter, The Deterrent, The Bodyguard, The Rock Star, and, in a modest bit of

self-examination, “ I’m not well placed to describe myself,

of course, but I suspect I’m a Twitcher, never to be found in his booth,

for fear of entrapment. ”.

— Bookride. 28 Sept. 09 : Five types of Book Dealer. Useful addition to the technical literature, describing the following types : The indigent bookseller, The grandiose bookseller, The humble bookseller, The pompous bookseller, and The raffish hustler. http://www.bookride.com/2009/09/four-types-of-book-dealer.html

Other citations are welcome.

A Writer’s Bookshelves

Eileen Gunn sent

pictures of bookshelves from Seattle (as promised), five of which

are included here :

27 September 09

The Function of Celtic Humor

“ verbal wit and linguistic dexterity in whatever tongue it might be expressed, a cunning born of a long history of being in the minority, the marginal, maverick even ”

— [Nicholas Currie]. The Book of Jokes. A Novel by Momus (Dalkey Archive Press, [2009]).

It was a snowy night late in June. My four uncles — The Englishman, The Irishman, The Scotsman, The Welshman — were on a hunting trip . . . you must remember that they were born before devolution made those states not only completely independent, but almost terra incognita to each other.

Tell you their names? But I already have. . . . On such occasions they would typically go hunting, shooting duck on a small island easily accessible from Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales.

One day, on just such a hunting trip, tragedy struck. In the midst of a particularly noisy fusillade, The Englishman crumpled to the ground, apparently felled by a stray burst of buckshot.

The Irishman, The Welshman and The Scotsman gathered around their stricken brother. Lacking my grandfather’s sang-froid , they panicked. . . . In the language of Scots Gaelic, Irish and Welsh, they explained the situation, each one tripping over the syntax of newly-learned languages . . . “ Now sir, calm down, ” came the reply, over all three phones, to all three men. “ We’d better use English. The first thing to do is make sure your friend is really dead. ”

There came three loud bangs — one, two, a short delay filled with horror, and then a third (The Irishman). “ Done ! ” chorused the uncles. “ Now what ? ”

As a lyricist, Nicholas Currie is deft and playful, occasionally brilliant, exposing the contradictions of modern urban culture to clear-eyed scrutiny, with special attention to constructs of identity. His performances in Philadelphia and New York earlier this year were captivating ; in the “ solo ” shows, Momus was stalked by a silent doppelgänger in black Japanese stagehand costume. I noted a fruitful list of dualities and juxtapositions : want/need, make/destroy, Pygmalion/Moreau, impotent/omnipotent, lament/disinfect, situationist lap-dogs/Beowulf, Valhalla/virus (Wagner/Burroughs) ; the range of associations was broad : from Edmund Wilson to Noh theater, from Beardsley and Wilde and decadence to the machinery of academia (“ bad but intimate poetry ”) and vaudevillean nostalgia.

In prose, Currie writes with flair and evident relish of the notion of writing within inventive constraints ; it is no surprise to find The Book of Jokes bearing the Dalkey Archive imprint. The Book of Scotlands (2009), published earlier this year but not yet seen, appears to be formally innovative also. There are hints of wide reading — from classical allusion to witty name-dropping and easy familiarity with the jargon of critical theory — as well as such Momus traits as appreciation for things Japanese and attentiveness to unusual garb and arcane detail. The Book of Jokes is in effect a dark and relentless taxonomy of the gross-out : incest, bestiality, brutality, whatever makes you cringe will rise from the pages. It comes as no surprise that the Skeleton family takes its holidays upon the presumably fictional Summerisle, located within rowing distance of the presumably real Isle of Bute and the pier at Rothesay Harbour. The narrator of The Book of Jokes alludes to the possibility of escape from the bad jokes that govern his world : “ The solution, I believe, is that I should assume, myself, the responsibility of telling the very jokes that restrain and define me, and to make, each time, a small alteration in their telling, an alteration which restores a few shreds of dignity, human decency, beauty, and sensualility to the tale. ” This tale is full of layering and distancing, and The Book of Jokes exercises upon the reader a certain squeamish fascination, or what Dickens called the “ attraction of repulsion ”. The Oblique Strategy “ Repetition is a form of change ” seems applicable here, as Currie runs a spiral of variations upon sick jokes.

It is not implausible to connect Currie with a Scots

literary heritage that reaches from Robert Burns to Ian Rankin, by

turns bawdy and visceral, dour and outrageous, and always conscious

of being in confrontation with the English respectable other (John

Buchan was so driven by the wish to assimilate with the establishment

of domination that he must be excluded : contrast Richard Hannay

and Dominick Medina in The Three Hostages ). There are

analogous strains of Irish, Welsh, and Catholic contrariness (Joyce,

Thomas, and Chesterton, to name three authors). It is also not unreasonable

to note here that these Celtic modes of resistance form the most interesting

portion of literature in English. The remarkable sentence by Adrian

Dannatt cited above is what prompted me to recognize Currie as performing

in this traditional mode ; else I would likely have abandoned The

Book of Jokes .

As Pól O’Dubhthaigh has remarked, “ I have never

been a cogent thinker, well maybe in [Toronto], but that was a long time

ago [. . .] I am also only part Irish, the other part is Scots/Manx,

which is the ontological equivalent of stating that I like to drink, but

I’m too cheap to pay for it, which is usually seconded by known Irish

purebreds with the quip that the difference between a Scotsman and a coconut

is that you can get a drink out of a coconut, which is then rejoindered by

the exclamation that were it not for the wheelbarrow, the Irish would have

never walked upright, and the Manx sit by and just watch the fisticuffs. ”

Or, in other terms : The Irishman, The Welshman, and The Scotsman each write a book (The Cornishman died young ; The Manxman had emigrated and the tax exiles know no Manx). The function of the three books varies : The Irishman evokes laughter and tears and dreams, and mocks the English ; The Welshman sings of nostalgia and kindness and anger. And The Scotsman celebrates the human body and its organic functions and discomforts. And then spits in your face.

The concluding sentence of the novel can only be read in this light. The Book of Jokes is a nasty, deliberate piece of work.

Doorway in ruined abbey, Ballina, Co. Mayo, 5542. W. L. (Lawrence Royal glass negatives, National Library of Ireland)

Born in the 1980s

— Catherine Browne, editor. Born in

the 1980s (Route,

2009 ; distributed in the U.S. by Dufour

Editions). Collection of 10 stories by Luis Amate Perez, Gareth

Storey, Katharine Coldiron, Sally Jenkinson, Chelsey Flood, Christine

Cooper, Sam Duda, Chris Killen, Alex Wire, and Amanda Rodriguez.

Interesting mix of well-written stories by authors in their 20s in

a variety of literary modes and a broad range of locales (from England

and Ireland to the U.S., South Africa, and Mexico). Gareth Storey’s “ Grainne ” is

a focused recollection of childhood dislocation and innocent friendship

that walks the precipice of sentimentality. “Brown Rice ” by

Sally Jenkinson is a closely observed domestic tale of a single father

and his mixed-race daughter in an unnamed city in the Midlands. “ Christopher

Robin is Cold” by Luis Amate Perez is at once a narration of

the end of an affair and a funny demonstration of how some artists

use their lives as material for performance. Christine Cooper’“ What

Am I Doing Here evokes the ambivalent emotions of an Australian

woman working in a South African orphanage ; in this piece — as

in several other accounts of inching towards responsibility or fleeing

it — one sees characters struggling to define themselves

and to learn what meaning their choices will have.

Born in the 1980s is designated Route 21, the most recent

in a series of short story anthologies.

Libraries in Danger :

The Pennsylvania State Senate passed a funding bill that averts a forced

closure of the Free Library of Philadelphia

http://libwww.freelibrary.org/donate/thankyou.cfm

‘ I fear he is a bad low animal ’

“ I fear he is a bad low animal. ”

The first description of the Toad in the first letter from Kenneth Grahame

to his son ; the preceding pages of the letter can be seen here.

In the exhibition of the manuscripts and archive of The

Wind in the Willows at the Bodleian :

http://www.ouls.ox.ac.uk/bodley/about/exhibitions/online/witw

Recent Reading

— John Francis McDermott. The Lost Panoramas of the Mississippi (University

of Chicago Press, 1958). Accounts of the five colossal painted “ moving ” panoramas

of the Mississippi executed for theatrical display in the late 1840s : the

rivalry of the artist entrepreneurs, the impossible claims for the length of

the canvases (“ the Biggest Picture in the World ”), and

the dwindling of public interest. This would seem to be the factual basis for

R.A. Lafferty’s “ All Pieces of a River Shore ” (1970).

— T.H. Clarke. The Rhinoceros from Dürer to Stubbs 1515-1799 (Sotheby’s

Publications, 1986). Illustrated history of the rhinoceros in Europe : the

Lisbon rhinoceros of 1515 that prompted Dürer’s iconic woodcut, and

the relationship among other images recording the rare specimens of the animal

that reached Europe.

— Alice Sebold. The Lovely Bones. A Novel (2002; Back

Bay books paperback). Posthumous fantasy of a murdered teenager trapped in an

intermediate state chiefly characterized by longing ; a horror tear-jerker

with some basic ontological and epistemological issues utterly unresolved. It

can be more precisely defined as a tale of supernatural revenge. Clearly your

correspondent does not form part of the intended audience.

Linguistic Dexterity in whatever tongue it might be expressed

From Adrian Dannatt’s superb memoir of his grandfather, Howell Davies, in the re-issue of Congratulate the Devil (1939 as by “ Andrew Marvell ” ; Parthian. Library of Wales paperback, 2008) :

“ Thus I grew up with the sense, never stated nor defined, that Welshness required verbal wit and linguistic dexterity in whatever tongue it might be expressed, a cunning born of a long history of being in the minority, the marginal, maverick even. That to be Welsh was to prefer the amusing or outrageous over the factual and actual, to believe the imagination more vital than any reality . . . ”

Davies, wounded in the Great War, was a friend of Robert Graves and compiler of The South American Handbook from 1923 to 1972 (described by Graham Greene as “ the best travel guide in the world ” ), and a contributor to the BBC on various topics. Dannatt’s foreword is delightful, and in such phrases as “ his flair for friendship ” and “ featuring a most amiable Welsh ‘ wandering minstrel ’, naturally an unemployed one ”, one gains a sense of how deeply Davies’ character shines though in his grandson. I can’t wait to read the book attached to the foreword.

600 years of Leipzig University

The Grolier Club in

New York City is host to a new exhibit (through 21 November 09) celebrating

the six hundredth anniversary of the founding of Leipzig University. In

Pursuit of Knowledge, curated by Dr. Ulrich Johannes Schneider, displays

some of the cultural treasures of the world that are found in the university

library (founded in 1543), including pages from Papyrus Ebers (1600 BCE),

from the Codex Sinaiticus (4th century CE), and from the medieval Machsor

Lipsiae. Leipzig was home to Germany’s publishing industry for centuries,

so it is natural that the Goethe collection of publisher Salomon Hirzel should

find a home there.

There is a well-illustrated website for the exhibit,

here :

http://www.inpursuitofknowledge.org/

The Bibliographical Way

“ Faith in the prime importance of the printed

source arises from the conviction that the content of the printed document

is, humanly and normally, the studied and reasoned belief of its writer,

presented carefully, in the hope of its withstanding criticism and

rebuttal. ”

Lawrence Wroth, “ The Bibliographical Way ” (1936)

The essay is cited in full by Richard Ring, Providence Public Library : http://pplspeccoll.blogspot.com/2009/09/bibliographical.html [N.B. Feb. 2013 : live link is now : http://pplspcoll.wordpress.com/2009/09/06/the-bibliographical-way/ ]

This is a compelling sentence for several reasons :

whereas text on a screen is infinitely malleable without showing traces

of re-working, a book is deliberate ; this sentence demonstrates

that the book has always been “ networked ” in

the sense intended by the folks at the Institute for the Future of

the Book ; and by fixing thought in print, the steps to any subsequent

re-thinking (or revision or explosion of theory or disavowal) must

then be made known.

Books are how human beings communicate across time (whether brief intervals

or long centuries) : in the words of Robert Irwin: “ In their

minds, they walked and talked with dead men ” (Dangerous Knowledge ,

2006).

Libraries in Danger

Philadelphia Free Library

Closing 2 Oct. unless budget assistance provided to city of Philadelphia

http://libwww.freelibrary.org/closing/

Providence Public Library

Gave away its branch libraries Jul. 09, still open

http://pplspeccoll.blogspot.com/2009/07/what-does-it-all-mean.html

13 September 09

Digital Poe at the Ransom Center

The Ransom Center at the University of Texas has The

Edgar Allan Poe Digital Collection, with numerous digital images of Poe

manuscripts and books — such as his annotated

copy of The Raven (1845) complete with a noisy virtual page-turning display

animation — and this November 1846 promissory note to his employer,

publisher Louis Godey :

http://research.hrc.utexas.edu/PoeGal/14/M_POE_POE_Godey001.jpg

A Reminder, and a Request

A Reminder : to browse back through the archives, which include Japanese

poems and a short course in micropublishing and mandrakes and

the narrative structure of Tristram

Shandy and found poetry and . . . the list is almost endless. And

perhaps a reader who is more technically proficient will suggest

a way to make these topics more easily discovered.

Current Reading

— George P. Pelecanos. Nick’s Trip (1993; Serpent’s Tail, 1999, paperback). Life in Washington, D.C.

— Rudy Rucker. Postsingular (2007 ; Tor paperback, 2009). Mind-expanding and comic. Rucker’s novels seem as loopy and paranoid as anything by PKD, but fundamentally much cheerier. Here are a couple of choice sentences from the mouth of Nektar, one of the essential minor characters :

“ So horrible, ” she choked out. “ So evil. So plastic. They’re destroying Earth for a memory upgrade. ” (32)

“ That man isn’t comfortable in a human body. He truly thinks we’d be happier if we were software.” (131)

And then there is this fine simile, fully earned :

Space twitched like a sprouting seed. (317)

The Institute for the Future of the Book

if:book blog http://futureofthebook.org/blog/

from the mission statement :

More profound, however, is the book’s reinvention in a networked environment. Unlike the printed book, the networked book is not bound by time or space. It is an evolving entity within an ecology of readers, authors and texts. Unlike the printed book, the networked book is never finished : it is always a work in progress.

As such, the Institute is deeply concerned with the surrounding forces that will shape the network environment and the conditions of culture: network neutrality, copyright and privacy. We believe that a free, neutral network, a progressive intellectual property system, and robust safeguards for privacy are essential conditions for an enlightened digital age.

http://futureofthebook.org/mission.html

Hommage to Ray Johnson in Chelsea

Wm. S. Wilson, who tends the flame of Ray Johnson,

held an open house to celebrate the artist’s work on Friday evening.

Wilson writes “ Ray’s collages can stand alone, but

with a little less meaning than when interrelated in clusters.” His

Ray Johnson room — a wall of collages — cultivates

that sense of interrelation just as Wilson’s conversation elucidates

context and further meaning. JohnsonÍs collages are direct in their

nature or effect, but not simple : the network of references they

embody is inherently complex.

Elsewehere in the same essay, With Ray : The Art of Friendship (published

in Ray Johnson , Black Mountain Dossier no. 4, 1997), Wilson

articulates a key issue in responding to Johnson’s work : “ One

can have the work of art, or one can have its sources. In tracing the work

to its sources it is lost, because as analysis disintegrates the whole into

parts, the parts lose their meaning, which is the bearing of part upon part

in the construction of a unified work of art. ”

Shall We Have a Little Talk ?

Every time I drink my tea (usuallly Lopchu Darjeeling in the morning, and

lapsang souchong or licorice in the late evening, depending upon the

hour or the deadline), I am reminded of the Robert Sheckley ironic first

contact story, “ Shall We Have a Little Talk ? ” (1965),

where the language of the aliens evolves at a far greater rate than the

human explorer (no slouch as a linguist) can adapt :

“ A language consisting of infinite variations on a single word ! ”

“ Mun mun-mun mun ? ”

— F. Gray Griswold. Old Madeiras (Duttons, 1929), published “ to remind those who love good cheer of a gentle American custom that has vanished from this arid land. ” This passage is a childhood memory from the late 1850s or early 1860s, after being permitted to witness a madeira tasting party :

I noticed that one guest had a special decanter in front of his plate and did not take any of the wines that were passed. I asked the butler to explain this the following morning. He said : “ Mr. Stagg does not drink wine so I prepare a decanter of cold tea for him. He pretends it is sherry. ”

4 September 09

— Rudy Rucker. Postsingular (2007 ; Tor paperback, 2009). Your correspondent has just picked this up to read while away from the computers that — at a glance — seem an inescapable part of this novel’s substance. A recent marginal gloss cited a Rucker dictum :

“You’re not doing your job as an SF or fantasy writer unless your readers wonder if you’re crazy.” — Rudy Rucker http://tinyurl.com/nnfzfv

— Rex Burns. Endangered Species (Viking,

1993). Denver police procedural, homicide investigation. Once federal

government entities are invoked, the stereotypes seems to blossom ;

and the very individualism that makes a detective novel of interest

is washed away in the bureaucratic protocols.

— Lawrence Block. All the Flowers are Dying (William

Morrow, 2005). Matthew Scudder novel, suspenseful but key points are telegraphed

and there are symptoms of series fatigue.

Neil Gaiman’s Bookshelves

From his online journal :

“

And, for the curious, this is what some of the downstairs library,

and Hermione

the Library Cat looks like. (I wish the upstairs library with all

the good reference stuff was in it too.) ” : http://blog.shelfari.com/my_weblog/2009/09/neil.html

Book Blog

Natalie

Galustian, London “ rare book dealer, writer, ideal

dinner guest ”, reviews R. GekoskiÍs “ self-portrait

refracted through the prism of a lifetime’s reading ”, Outside

of a Dog. A Bibliomemoir (Constable, 2009) in the first

entry of a new blog.

http://nataliegalustian.wordpress.com/

3 September 09

Recent reading

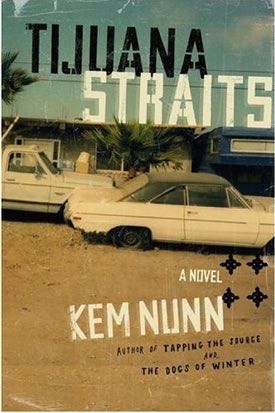

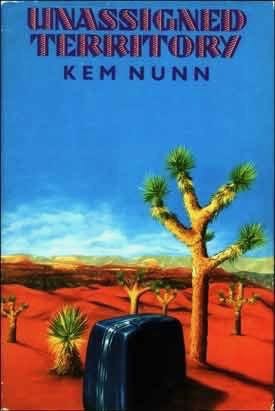

— Kem Nunn. Tijuana Straits. A Novel (Scribner, 2004). Grim, visceral novel with brilliant evocation of the borderlands, the California no one notices. Unassigned Territory (1986) has remained on my shelves and in my vocabulary since I first read it. Tijuana Straits has no intrusion of the fantastical but it is filled with similar razor-edged observations of the human and geological landcapes. Nunn is a dark writer, but his books have a flavor of optimism absent from the books of Paco Ignacio Taibo, for example.

[The Scribner name survives, swallowed by Simon & Schuster : the company founded in 1924 by Dick and Max, the boys who sold the first crossword puzzle book, has absorbed the venerable firm that published Hemingway and Fitzgerald ; another form of the name, Charles Scribner’s Sons, survives as a reference book publisher, an imprint of Gale. Both imprints trace their origins to the same date (1846).]

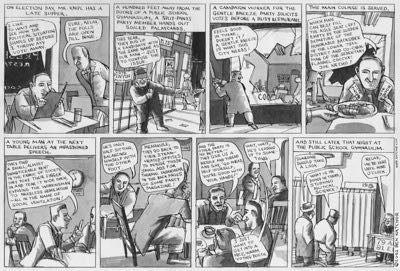

— Ben Katchor. Julius Knipl Real Estate Photographer. Stories. Introduction by Michael Chabon (Little, Brown, 1996). Re-reading this. “ Composed each day under the nonchalant supervision of countless security guards are these fascinating chronicles of the comercial life of the city. Hastily written, in turn, by the participants themselves, they form an epic tale of urgent comings and goings, strange family names and mysterious business transactions conducted at all hours of the day and night. ” And what a gift Katchor has for names of defunct enterprises, minor characters, and the nostalgic evocation of a vanishing city that never existed.

Some years ago, your correspondent had the pleasure of attending the New York premiere of The Rosenbach Company , Mark Mulcahy & Ben Katchor’s musical biography of the brothers Rosenbach, the greatest American antiquarian bookseller of the first half of the twentieth-century. The opera, composed at the behest of the Rosenbach Foundation, makes fine use of Katchor’s visual and verbal wit. One of the recurring musical motifs was the address of the firm in Locust Street, Philadelphia. I attended the premiere (performed by Mulcahy & Katchor) in the company of two foundation board members and a bookseller, now retired, who had a fair claim at being the Rosenbach of his generation. JoeÍs Pub in the Public Theater is an intimate space, and our table was almost on top of the minuscule stage ; my companions’ muttered asides earned us the dubious honor of being shushed by the author.

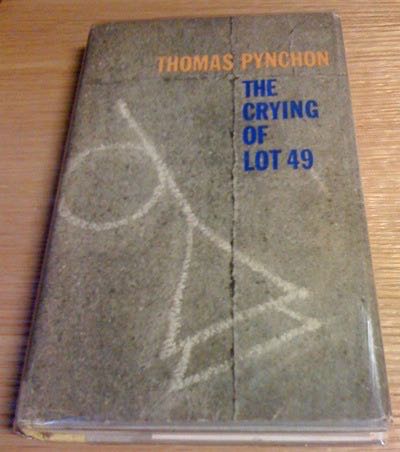

WE AWAIT SILENT TRISTERO’S EMPIRE

Note the conjoined R and post horn : the device on the postmark would seem to indicate that Romania is now a division of Yoyodyne, Inc. (and that even the post horn of the Thurn und Taxis/Tristero conpiracy is subject to brand redesign ; in the name of sensitivity to local aspirations and conditions, I suppose). N.B. The parcel and its contents (books) are unrelated to these digressions ; or, at least, the books describe different alternities.

There are a couple of sentences in The Crying of Lot 49 that linger :

She had dedicated herself, weeks ago, to making sense of what Inverarity had left behind, never suspecting that the legacy was America.

And, especially :

She stood in the patch of sun, among brilliant rising and falling points of dust, trying to get a little warm . . .

Cover Titles

The title page of a book serves a purpose : to identify title of the

book and the author (or to dissemble about the author, when a book is published

anonymously or with a pseudonym). In some cases, the title page will stake

out a design or aesthetic position beyond the merely utilitarian. Your correspondent

is a firm champion of the title page, and will also stand firm about the

distinction between the cover and the contents of a book. I concur with Teresa

Nielsen

Hayden’s definition of

the covers or dust jacket of a book as, functionally, a poster advertising

the book.

Sometimes, however, it is hard, very, very hard to hold this position.

Consider the cover information from the latest crop of mysteries to land

in the post office box of Temporary Culture (actual titles and authors are

omitted) :

A Glassblowing Mystery . . . Includes Glassmaking and Gem Lore

A Renaissance Faire Mystery . . . Includes Renaissance recipe and

fun facts !

A Decoupage Mystery . . . Decoupage tips, techniques, and project

ideas included !

Chintz ’n’ China Mysteries . . . Charm recipe included !

[series title from front matter]

A Bear Collector’s Mystery

I am willing to grant that each of these authors may be responding to Raymond

Chandler’s point that

The private detective of fiction is a fantastic creation who acts and speaks like a real man. He can be completely realistic in every sense but one, that one sense being that in life as we know it such a man would not be a private detective.

And yet . . . for the writer (as for the reader), style is everything : what does the creep of marketing materials (recipes and tips) into the book reveal about the author, reader, and reading in the twenty-first century ?

This creaking and constantly evolving website of the endless bookshelf : I expect that some entries will be brief, others will take the form of more elaborate essays, and eventually I will become adept at incorporating photos or comments and interactivity. Right now you’ll have to send links to me, dear readers. [HWW]

electronym : wessells at aol dot com

Copyright © 2007-2009 Henry Wessells and individual contributors.

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.