On a sea journey

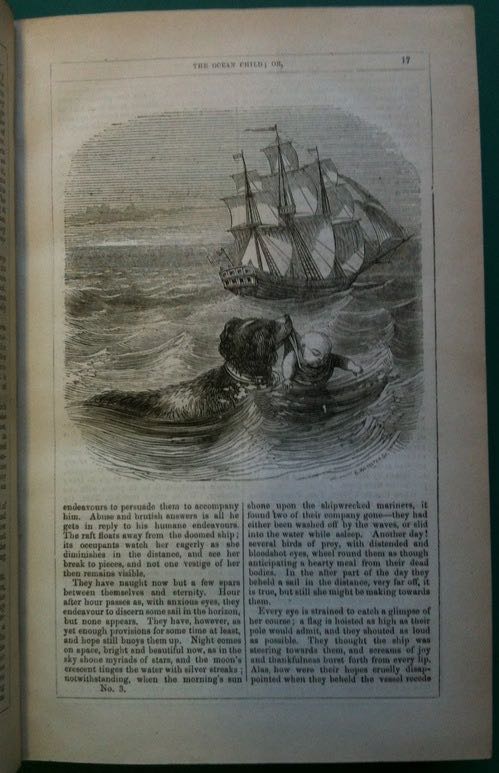

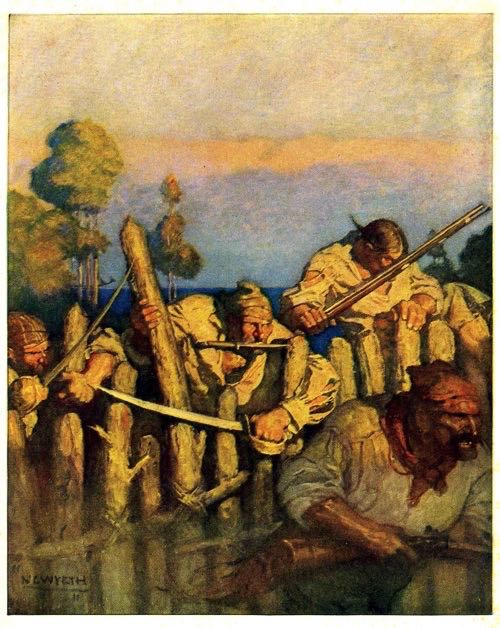

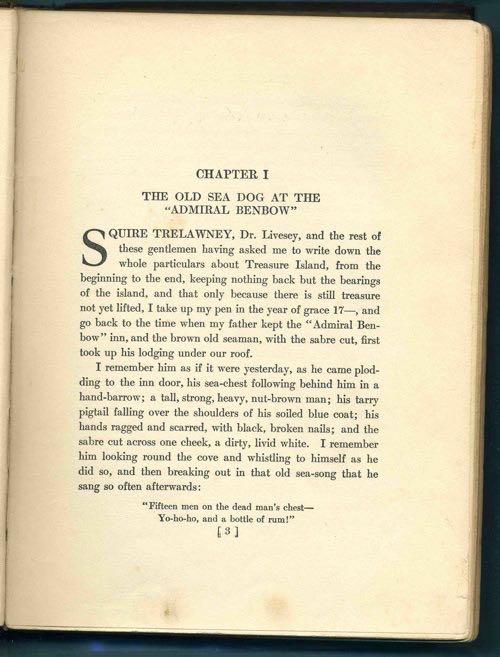

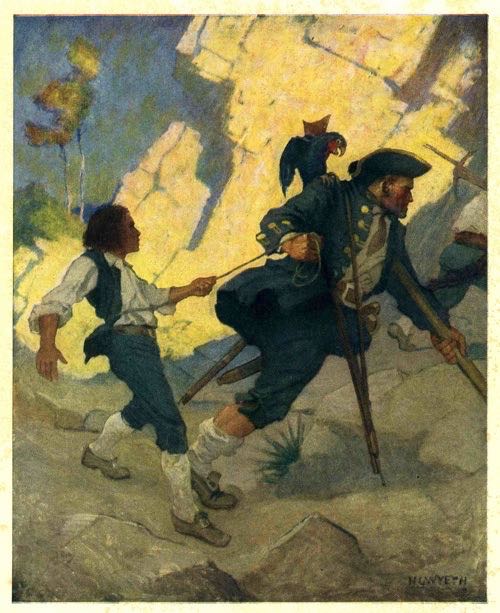

— Robert Louis Stevenson. Treasure Island. (1883 ; with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925). Later Scribners edition (the first Wyeth edition was 1911). Black cloth, upper cover with pictorial onlay. Worn, shaken, plates with some foxing, ink stains across page 104, not overly affecting legibility. This copy has been read by generations of readers and your correspondent is going to re-read it again. The Wyeth illustrations seem to me an inseparable part of Treasure Island, perhaps because it is in this edition (and this very copy) that I first encountered the book.

How can anyone resist the tale that begins :

As Brian Stableford notes in the Encyclopedia of Fantasy , “ while wholly lacking in supernatural elements, this adventure is so fantasticated that it is hard to regard it as outwith the fantasy genre ”. It is a book at the heart of the literature of the fantastic, for Stevenson used the terrain of history and the richly colored fabric of the English pirates to create another world. The ‘ sea-cook ’, Long John Silver, is a great and compelling character, a “ very remarkable man ”.

And we are now almost as far removed in time from the book as Stevenson was from the wild days of the middle of the eighteenth century and

the sharp voice of Captain Flint still ringing in my ears: “ Pieces of eight ! Pieces of eight ! ”

A Request from Your Correspondent

As the Endless Bookshelf nears the completion of four years in its present form, the thoughts of your correspondent turn sometimes to complex matters : what do the readers enjoy, or want, or lack ? It is always delightful to be told by a friend when I see him or her by chance or after long absence, still more so when when the communication comes unexpectedly. And when the letter or message prompts new modes of thought, even better still !

Please send a note with your likes, dislikes, or suggestions

for the website to :

wessells

at aol dot com .

This means you, DS, WW, and you other far-flung readers.

Your correspondent also asks, specifically, if any effort need be made to improve the structure of the website or the organization of the archives ? Or, in other words, can you find what you are seeking (whether that aim be diversion or specific information) ?

The next update to the Endless Bookshelf will appear on 1 December.

Angela Carter

I have finally read my way through the stories of Angela Carter, Burning Your Boats , an intense and very instructive project. She played with the modes of the fairy story and made made the words dance in unexpected ways, made the stories tell themselves in ways that they simply could not have done in earlier centuries. J.G. Ballard’s Cinderella story (remembered, not re-read) feels clinical and flat in comparison with the blaze of her reworkings of tales. As a practitioner of the critical fiction, I think that “ The Cabinet of Edgar Allan Poe ” was one of the most interesting ; and in attempting to understand how she got there, it did seem that in the early story “ Master ” she accomplished something that pointed the way forward. And “ The Erl King ” is one of the most layered, complex, and beautifully written accounts of a walk in the woods.

Of Inconvenient Obstacles and the ‘ reading transaction ’

“ physical books will go away because fair use is an inconvenient obstacle to maximizing publishing revenue (which makes publishers wealthier, but will not improve the lot of writers). The electronic format of ebooks represents the ultimate bonanza for publishers : the ability to insert a tollbooth in front of every reading transaction. ”

— K. G. Schneider, http://freerangelibrarian.com/

Never have I read so perfect a summation of the issues at stake in the intersecting worlds of libraries, book making, publishing, and reading. And what a brilliant, chilling insight that a “ reading transaction ” is the basic nature of the electronic book.

22 November 10

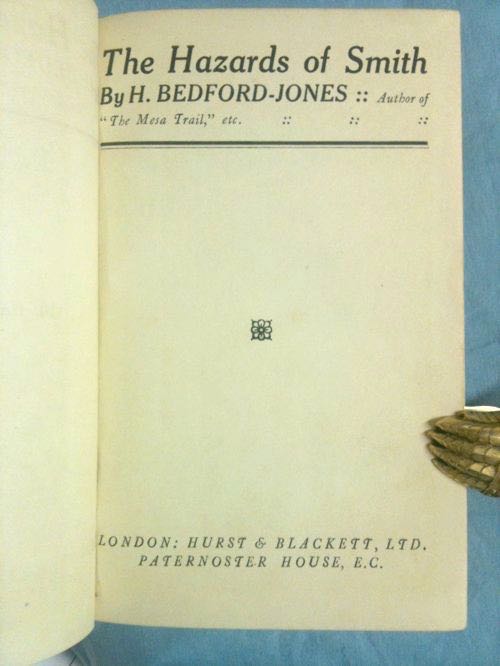

— H. Bedford-Jones. The Hazards of Smith. London : Hurst & Blackett Ltd, Paternoster Row, E.C., [n.d., 1924]. 288 pp. plus 16 pp. publisher’s catalogue. Green cloth stamped in black. Worn, endsheets darkened.

This is a book that I have had on my shelves since I picked it up as a teenager, probably in France. It consists of four linked novellas or novelets (First Hazard : The Magic of Ngong ; Second Hazard : The Second Life of M. le Diable ; Third Hazard : Blood of the Eagle ; and Fourth Hazard : The New Iseult). The stories are set in French Indochina and feature Say-and-See Smith. Classic adventure fare with evil criminals, info-dumps, exotic terrain, and equally exotic women (see below). I have always remembered the setting of the second hazard, an isolated island with a rich man’s luxury compound. Smith has enough official standing that the book earns a citation in the addenda to Hubin’s Crime Fiction III. A Comprehensive Bibliography listed deep in the Locus website. Three years ago when I made a passing mention of the book while thinking about “ Dead Money ” in Lucius Shepard’s collection Dagger Key , that was the only citation that came up in an open search online.

H. Bedford-Jones (or Jones, Henry James O’Brien Bedford, as he is known to the British Library) was a prolific Canadian-born magazine writer of adventure and fantastic fiction from before the first world war through the late 1940s. The entry in the Encyclopedia of Fantasy records numerous pseudonyms, including Allan Hawkwood, and that Bedford-Jones wrote tales on last race and yellow peril themes, as well as westerns and historical fiction. There are even a couple of books of poetry, including Corn, Wine & Oil (Santa Barbara, Calif. : privately printed, 1918 ; 40 copies, four of which are in libraries).

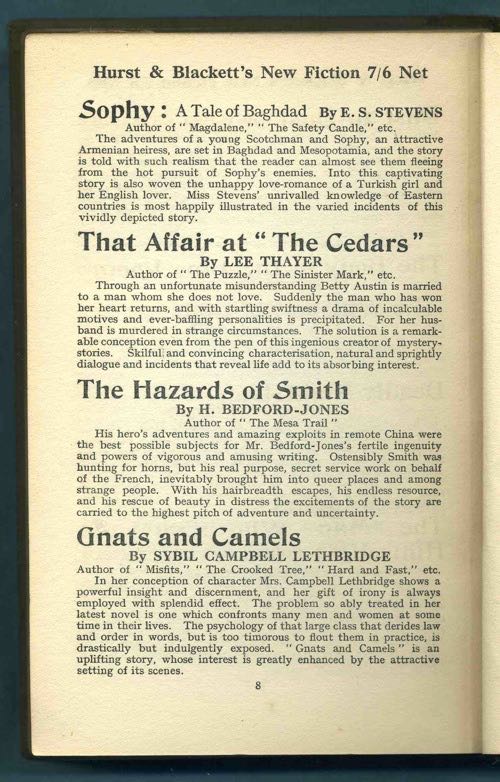

There is no doubt Bedford-Jones was prolific. The catalogue of the HRC at the University of Texas lists many of the magazine stories individually and records more than 250 entries. In Britain, he was published by Hurt & Blackett during the 1920s, and the catalogue in the back lists current titles, such as Cynthia Stockley’s Poppy, 177th thousand in the 3/6 Novels, and more than one by (Miss) E.S. Stevens (travel : By Tigris and Euphrates ; and fiction : Sophy : A Tale of Baghdad ) as well as The Hazards of Smith under New Fiction at 7/6. What I did not know until today is that a search of library holdings turns up only two copies of the book : in the British Library and the National Library of Scotland.

19-20-21 November 10

David Godine Exhibition at the Grolier Club

Tuesday evening was the opening of a new exhibition at the Grolier Club, celebrating forty years of printing and publishing by David R. Godine. David was there, beaming and surrounded by friends. He is without equal in American publishing ; there is no other firm whose books are so consistently beautiful, interesting, and well made. The poster (above) is by Glenna Lang. The exhibition, on the second floor gallery, is representative and surprising, and runs through 7 January 2011.

To maintain in all books the highest production standards ; to produce books of typographic distinction that provided some charm while not calling undue attention to themselves as ‘ fine press printing ’.

I have been a fan of Godine books for many years, officially since my days at AB , where the second book I was given to review was a Godine anthology of essays, Reading in Bed , edited by Steven Gilbar ; and I remember how I came to look for the handwritten notes in the margins of the form letters accompanying real books on subjects of merit, such as W. D. Taylor’s book on The Woodcut Art of J. J. Lankes — an artist overshadowed by Rockwell Kent — or Alex Karmel’s charming memoir of Paris, A Corner in the Marais ; and I was given the first volume of Arthur Ransome’s Swallows & Amazons series with the publisher’s knowning certainty that I would buy the rest of the dozen volumes and read them to my daughter (I did so). There are many other Godine titles among the favorites of the Endless Bookshelf. In addition to the printed keepsake, guests at the opening were given David Godine : the Letterpress Years , an offprint from the fine press journal Matrix , a memoir of the early years of his press which includes the excerpt from the firm’s original prospectus noted above.

One of the pleasures of the exhibition is to learn of several interesting books to look for and read ; another was to see David’s anthology Lyric Verse, A Printer’s Choice (1966), printed while he was a student at Dartmouth, and to learn read of Alfred A. Knopf’s response : a pointed note and a pamphlet concerning copyright law.‘ You say you ate every page of it ? ’

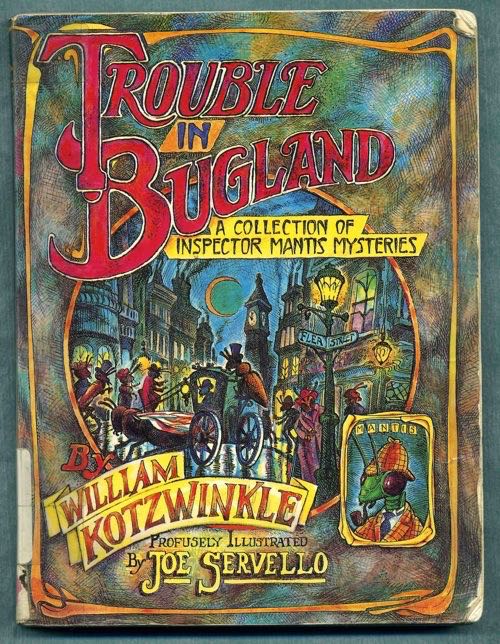

— William Kotzwinkle. Trouble in Bugland. A Collection of Inspector Mantis Mysteries . Profusely illustrated by Joe Servello. (1983 ; Godine Storyteller paperback, 1986).

A bugout hilarious Holmesian pastiche, with the lean, obsessive Inspector Mantis and the dogged, comfort-seeking Doctor Hopper, brisk action, pitch perfect narration and snappy dialogue with some sly gleams of humor in addition to the evident whimsy and fun. “ ‘ Of what possible use could a bareback riding butterfly be to them ? ’ ‘ Of inhuman use, so cruel as to compare to nothing we’ve ever dealt with before. ’ ”

The drawings by Joe Servello are superb, as though one has walked from the bucolic Ernest Shepard illustrations of The Wind in the Willows into a steampunk (bugpunk ?) Victorian world of stews, dark alleys, and madly detailed insects : Mantis wears a deerstalker and Inverness cape when out on the chase, and a tasselled fez while at home ; Doctor Hopper playes the violin (fair enough, for a grasshopper), is devoted to popcorn, and bakes when at home, wearing an apron edged with lace.

The Case of the Frightened Scholar is great, starting with a visit to the house of Professor Channing Booklouse: “ soon after I digested it, I realized that it had been more than just a history of Bugland . . . I had somehow thoroughly digested the most secret information about the highest workings of the Admiralty ! ” His specialty is the history of Bugland, his library filled with the empty covers of books. “ The contents have all been chewed over thoroughly, night in and nght out, until nothing is left. My research has been complete . . . . ” There are echoes of H. Rider Haggard in The Case of the Caterpillar’s Head, and The Case of the Headless Monster has a lovely, touching final cadence. In the final adventure, Mantis is joined by an old school friend Walking Stick, “ a dreamy sort of fellow ”, whose notions of intellectual challenge are a tangent to the crimes Mantis investigates, and which allow Kotzwinkle to explore “ the three mysteries of Bugland ”.

‘ The Man with the Knives ’

A timely reminder that only about fifty (50) copies remain available of the trade issue of the current title from Temporary Culture, Ellen Kushner’s The Man with the Knives . Details on ordering are to be found here.

‘ soon he learned to tell the difference between Hera and hs mother ’

— Gregory Feeley. Kentauros . [NHR Books, 2010]. 98 pp. $15.00

In Kentauros , a concise, carefully crafted book in six parts, Gregory Feeley invokes the little known myth of Kentauros, outcast son of Ixion and a cloud simulacrum of Hera raised on Olympus, whose earthly dalliance with a herd of mares engendered the race of centaurs. As its subject crosses boundaries between the realm of the gods and men, Kentauros moves nimbly between fiction and nonfiction : it is a playfully intertextual novella that moves between ancient Greece and the Byron circle in Italy just after the death of Shelley ; and a series of postmodern reflections upon the origins of myth and the nature of monsters. Kentauros is rooted in a late eighteenth century translation of Pindar, where the sole classical reference to the origin enters English literature — Trelawney reads from a copy found in Byron’s library in the brilliant fourth section, where Feeley sketches the dark fortunes and blazing intellect of Mary Shelley and shows that he has mined the recent biography of Leigh Hunt to excellent dramatic effect. The second and sixth parts trace the experiences of Kentauros as he makes his way from an existence outside of time into the world of men. The diction links the imagery of Pindar and Shelley’s predilections with creation, power, and clouds. Feeley’s erudition is rich in humor, too : when was the last time you encountered a satyr who quoted Wordsworth ?

The satyr snickered. “ ‘ I wandered lonely as a cloud, ’ ” he said.

The story of Kentauros is a characteristic Feeley subject, arcane, overlooked, at the edge of creation : not at the border where magic turns into science or renaissance commerce turns into state capitalism — as many of his earlier works have been, such as novellas “ The Weighing of Ayre ” and “ Fancy Bread ”, or Arabian Wine (published by your correspondent in 2005) — but at the very spring from which flood myth and imagination.

With Frankenstein ; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), Mary Shelley unleashed a myth upon the world. * In doing so, she struck sparks that would become a burning new literary mode. After her husband’s death by drowning, and the death of Byron — a friend and ntellectual equal — it is little wonder that she wrote The Last Man (1826), a wrenching study of loss that confirms her status as the founder of science fiction.

In section four of Kentauros , Leigh Hunt sends Mary Shelley a letter, “ with its wide-eyed profession of ingenuousness and its hidden malice ”, and a heavy sheaf of verses he suggests were composed by Shelley. If the portrait of Mary Shelley that Feeley offers is of a widow narrowly circumscribed by financial poverty, it is also of a clear sighted woman of genius. She can discern the selfish motives of Leigh Hunt in attempting to pass off one of his poems as though by Shelley. She takes a flint and steel. “ This time the sparks sent up an immediate curl, and Mary pushed in the papers as quickly as she dared. Like infected clothes, they burned. ” Some might argue that Leigh Hunt was merely a talented opportunist in the company of writers of geniuses ; I read his character in a darker light.

Kentauros is the rediscovery of an elusive myth and a graceful story that moves to a brilliantly written conclusion. The book’s final sentence is deft, beautiful, mysterious.

* Few other modern writers can make such a claim : perhaps Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. G. Wells, and Jerry Siegel.

Daily dispatches

Your correspondent will be updating the Endless Bookshelf daily for the next several days in response to reader demand.

Communications are welcome, including updates on the Last Three (books read).

— — — —

— Gregory Feeley. Kentauros . [NHR Books, 2010].

Newly received (and to be published on 7 December), Gregory Feeley’s latest book is an exploration of myth and postmodern theory, an evocation of literary history, braided with a gracefully written story ; a short essay will follow later today. As it happens, I had just read a book that is essential to understanding certain aspects of the story and of Feeley’s thought.

— — — —

Recent reading :

— Mary Shelley. The Last Man (1826 ; edited with an introduction by Hugh J. Luke, Jr., University of Nebraska Press, 1965).

It is the late twenty-first century and the last King of England has abdicated his throne to live as the Earl of Windsor under a republican government. During the narrative arc of The Last Man , a plague spreads unstoppably from the mysterious east into Europe and across the channel to England. Every one dies save for Verney, the last man. The Last Man is a devastating account of loss — the characters are recognizably avatars of Byron and Shelley, and Verney’s sadness is profound and transcendant. It is a work of fantastical literature that, like Frankenstein (1818), establishes some foundations of the science fiction mode : Difficulty (Mary Shelley is an undisputed master), Displacement (writing about the present while presenting an exotic future or world), and Wild Imagination. This is a book that had been on the To Be Read list for many years ; The Last Man is one of the highlights of a year of good books.

In Trillion Year Spree (1986), Brian Aldiss traces the progress of the plague in the 1820s and writes, “ Mary Shelley, in The Last Man , was hardly doing more than issuing a symbolic representation, a psychic screening, of what was taking place in reality. In that, at least, she was setting an example to be followed by the swarming SF scribes of the twentieth century. ” From Shelley’s “ Ozymandias ” to this passage from The Last Man is a single step and a vast imaginative leap :

The vast cities of America, the fertile plains of Hindostan, the crowded abodes of the Chinese, are menaced with utter ruin. [. . .] Persia, with its cloth of gold, marble halls, and infinite wealth, is now a tomb. The tent of the Arab is fallen in the sands, and his horse spurns the ground unbridled and unsaddled. The voice of lamentation fills the valley of Cashmere ; its dells and woods, its cool fountains, and gardens of roses, are polluted by the dead ; in Circassia and Georgia the spirit of beauty weeps over the ruin of its favourite temple — the form of woman.

I do not know if Sylvia Townsend Warner, author of Lolly Willowes, knew Mary Shelley’s novel, but her passage about the end of civilization seems in the direct line of descent.

Mary Shelley’s rôle in originating science fiction is primary, but the mode has its origins in the varieties of the Gothic, a literature that, in England, arose in the late 1750s ; it spread throughout Europe and to America as well. One of the characteristics of science fiction, from the outset, is intertextuality. As Lionel Verney reflects on the progress of the mysterious disease, authors such as Boccaccio, De Foe and Browne are mentioned ; Verney actually knows the plague through literature as well as through direct, face to face contact :

I had never before beheld one killed by pestilence. While every mind was full of dismay at its effects, a craving for excitement led us to peruse De Foe’s account, and the masterful delineations of the author of Arthur Mervyn.[*] The pictures drawn in these books were so vivid, that we seemed to have experienced the results depicted by them. But cold were the sensations excited by words, burning though they were, and describing the death and misery of thousands, compared to what I felt in looking on the corpse of this unhappy stranger. This indeed was the plague.

* Charles Brockden Brown. Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 . By the Author of Wieland. Philadelphia : H. Maxwell, 1799 ; the second part of the novel was published the following year in New York. A novel set against the yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia ; Brown was deeply influenced by the political and literary thought of William Godwin, author of Things As They Are ; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794) and the father of Mary Shelley.

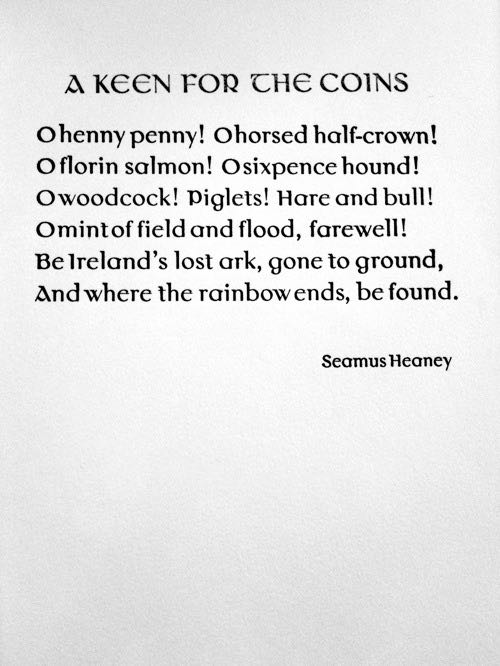

Seen (and Memorized) in Boston :

This is a black and white picture of a small broadside printed in brown and grey ; seen (and memorized) at the Maggs Bros. stand at the Boston Antiquarian Book Fair. [Thanks to Joe McCann].

Current reading :

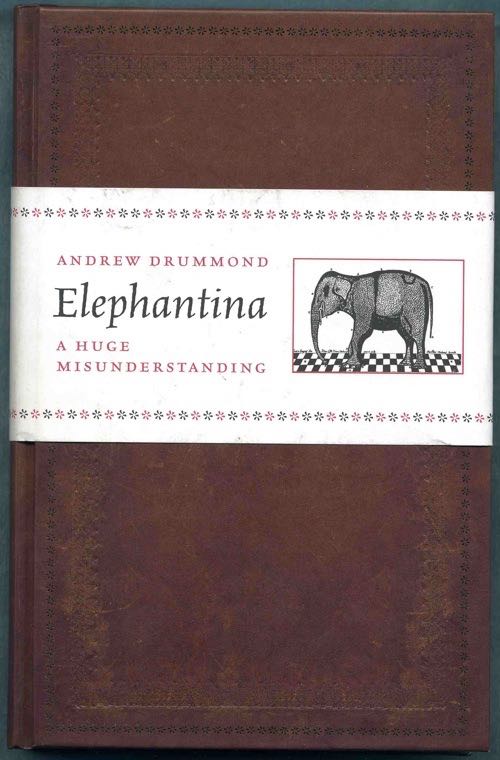

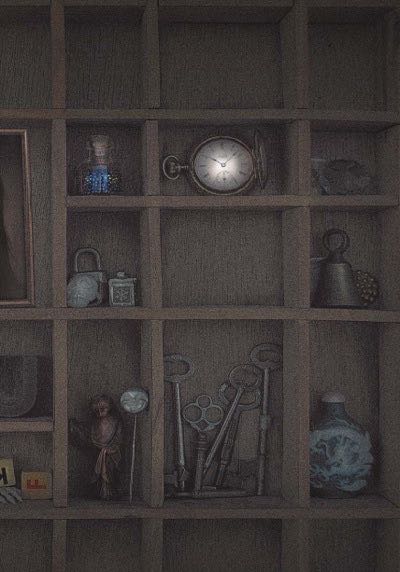

— [Andrew Drummond. Elephantina. A Huge Misunderstanding ]. An Account of the Accidental Death of an Elephant in Dundee in the year 1706, described by an Engraver resident in that Town. Together with some Short Remarks on the Hall of Rarities , and the Life of Dr. Patrick Blair , including Extracts from his remarkable Essay Osteographia Elephantina Taodunensis, published by The Royal Society of London in 1710, the Whole Presented to the Public by ‘ Senex ’, Dundee, 1830. [Edinburgh : Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn, Ltd., 2008].

This novel is a complex, hilarious philosophical elephant, at once a layered satire upon history, science, and the pedantry of the serious-minded nineteenth-century “ editor ”, and a compelling account of life and dissection in Dundee (and yes there is even a sly allusion to “ Mr. K. ”, confectioner). The book, narrated by engraver Gilbert Orum, is formed in imitation of a drab calf-bound volume, and the delightful title, Elephantina. A Huge Misunderstanding , appears on a wrap around band (the half title simply reads Elephantina ) ; a title page transcription is given above. Clearly there is a bit of the spirit Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things (1992) at work here, but Dundee is not Edinburgh, very much not. I am about halfway through the book, which first came to my attention in a note from David Langford about Avram Davidson. I am glad I tracked down a copy. [And I have posted a larger picture.]

7 November 10

Recent reading :

— Mark Valentine. A Revelation of Cormorants . [Manchester :] Nightjar Press, [September 2010]. 15 pp., pictorial covers. A fine story of avian folklore and wanderings on the Galloway coast, in the conte cruel mode. This was waiting in the post box when I returned from last week’s travels to London and Yorkshire.

I had the pleasure of meeting the author at the Halifax Ghost Story Festival on Saturday 30 October, where he spoke on author William Freyer Harvey, the “ secret room in his childhood house ”, and his memoir We Were Seven (1936). I have known of Valentine’s books for some time, but had never met him before. Gail-Nina Anderson gave an excellent talk on a Rossetti painting of his late wife and all the ramifications of image, allusion, and conjecture. Reggie Oliver read a new story “ Minos or Rhadamanthus ”, a beautifully paced and carefully crafted ghost story of the Edwardian era that is decidedly modern in its reversal of expectations. I shall look out for his work. Lunch with Mark Valentine, his wife Jo, and Gail Anderson was a congenial and wide-ranging conversation — what a pleasure to talk about literature and art and music with sharp intellects.

— R.B. Russell. Literary Remains . PS, 2010. [vi], 195 pp. Hardcover with pictorial dustjacket by Jason van Hollander. Collection of 10 strange stories by the publisher of Tartarus Press. An excellent gathering with several unsettling tales with images and endings that refuse the single interpretation. “ Llanfihangel ” and the title story are particularly effective. I picked this up at the Halifax Ghost Story Festival last week, along with these two titles :

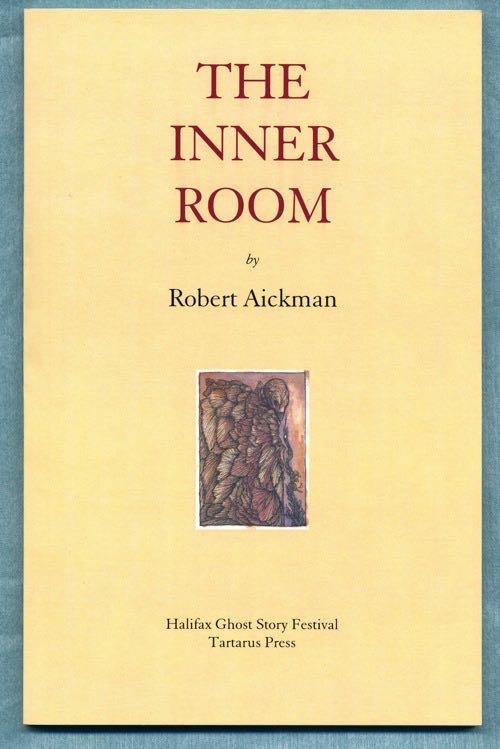

— Robert Aickman. The Inner Room .

Halifax Ghost Story Festival, Tartarus

Press, [2010]. [viii], 51, [5] pp. Paper covers.

— Robert Aickman. Sub Rosa . Tartarus

Press,

2010. Collection

of 8 stories, first published by Gollancz (1968) ; with a new introduction

and notes by R.B. Russell. Published at the Halifax Ghost Story Festival,

30 October 2010. [6], v-ix, 291 pp. Hardcover in dust jacket, with a cover

similar to that

of The Inner Room . The cover drawing is by Stephen J. Clark,

“ The

Interloper ”.

Somehow, despite the best efforts of Michael Walsh

and other friends, I had not read Aickman until I picked up these two books.

I

now understand

the profound

appeal and count myself an Aickman fan. In his opening remarks at the Halifax

Ghost Story Festival, Ray Russell paraphrased Aickman and pointed to the structure

of these

tales : “ the

absence of the ghost does not dispel

the strangeness ” — a long way from M. R. James, indeed. The

Inner Room is a beautiful, very chilly narrative ; the slow,

almost reluctant pacing

of “ The

Unsettled

Dust ” is perfect ; and “ Into the Wood ” is

simply remarkable !

This

sentence, from “ Ravissante ”, seems

a

characteristic

Aickman

observation :

“ Human relationships are so fantastically oblique that one can never be sure. ”

— — — —

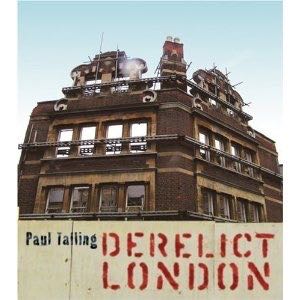

— Paul Talling. Derelict London . RH Books, [2008] (fifth printing). 222 pp. Excellent little book documenting the shifting tides of urban life in greater London, good pictures taken with an eye for small details and the way city ruins sometimes open into strange vistas. The text is idiosyncratic and anecdotal rather than dry, the geographical range is tireless, and the small square format is very pleasing. The book is an outgrowth of Talling’s Derelict London website.

Autumn wall on Regent’s canal (not a derelict site)

Autumn wall on Regent’s canal (not a derelict site)

Walking north from Camden Town along the canal to King’s Cross last week, I passed several areas that had almost a rural air (pumpkins under a tent in a thicket or coppice behind the St. Pancras yacht basin) but which are slated for massive redevelopment in the near future.

Inefficiencies

“ The only way you can know things like that is by imagining them. You can’t ever know what Betty was like but you can imagine what it was like to be Betty. ”

— Peter Dickinson. Tefuga. Pantheon Books, [1986].

I had not quite finished with Tefuga , a narrative dance between incident in the colonial past and events in the present of the novel. Several passages are worthy of note, such as this remark by documentary journalist Jackland :

‘ The trouble with that, Major, is that the gun has limited usefulness. You can point it at a chap and say “ Do this ” and he probably will, but it’s different when you try saying “ Be this ” or “ Be efficient ”. [. . .] I’ve seen a whole range of political systems, and I promise you that for all the inefficiencies of democracy, which I admit can be ghastly enough, the inefficiencies of force outweigh them every time. ’

Dickinson’s thoughts on power grabs and self-interest transcend Nigeria : “ Anyone who is not a fool can perceive the benefits of honest government, but that does not necessarily mean he can feel them in his heart. Your father and his kind actually felt deep admiration for probity, and determination to show it themselves, but they did not manage to instil the feeling in the peoples they ruled. All they have left us with is the rhetoric of probity. ”

Advertisement, 9 April 1925

Advertisement, 9 April 1925

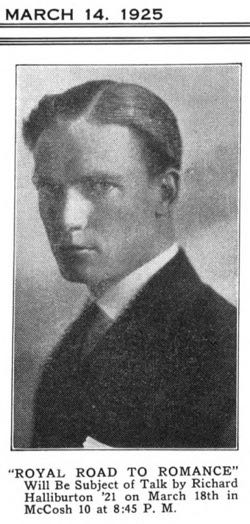

In 1925 two young Princetonians published books that would come to define their writing lives. The Great Gatsby and The Royal Road to Romance offer an interesting study in parallels and contrasts : in degress of celebrity and obscurity ; in early promise and untimely death.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, Princeton class of 1917, was already well-known for This Side of Paradise (1920) his portrait of the “ lazy and good-looking and aristocratic ” Princeton. In 1925 Scribner’s published The Great Gatsby , a book that Fitzgerald and his editor Maxwell Perkins knew to be his best work, a “ remarkable book ” about which T. S. Eliot wrote “ it seems to me to be the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James. ” An advertisment for Fitzgerald’s novel first appeared in the ‘Prince ’ in April ; it was reviewed in May. A decade later, Fitzgerald’s career was in eclipse ; the story of his complicated life is well known. It is important to remember that the entry of The Great Gatsby into the literary canon was posthumous.

Fitzgerald’s friend Edmund Wilson wrote of This Side of Paradise “ the chief weakness is that it is really not about anything: its intellectual and moral content amounts to little more than a gesture — a gesture of indefinite revolt. ”

That “ gesture of indefinite revolt ” is not too far removed from the spirit of discontent that drove Richard Halliburton, Lawrenceville class of 1917 and Princeton class of 1921. He set off for Europe and Asia upon graduating and his early travels were part adventure (climbing the Matterhorn) and part provocation (taking pictures in a restricted part of Gibraltar). These voyages formed the basis for his first best selling book, The Royal Road to Romance . He made numerous visits to Princeton.

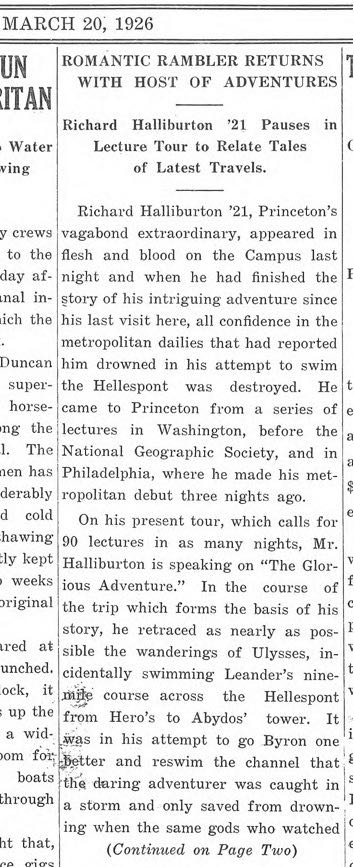

The Daily Princetonian : 20 March 1926

Halliburton’s travels became more ambitious, re-tracing the route of Ulysses in the Odyssey , crossing the Alps on elephant in Hannibal’s footsteps, swimming the Hellespont like his hero Lord Byron, flying to Timbuktu in an open biplane ; his fame continued to grow with succeeding books The Glorious Adventure (1927) and The Flying Carpet (1932).

Halliburton’s proposed biography of poet Rupert Brooke was rebuffed by Brooke’s mother (but his researches were used by biographer Arthur Springer). In March 1939, at the height of his celebrity, Halliburton “ left Hong Kong in a junk he planned to sail to the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. The vessel was unseaworthy and manned by a ragtag crew. Halliburton was plagued with money worries, but he set sail anyway. A little more than two weeks after leaving Hong Kong, the junk was caught in a typhoon, and radio contact was lost. Neither Halliburton nor his crew was seen again ” (ANB). His papers are held in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Fitzgerald’s star has risen ; Halliburton, “ Princeton’s vagabond extraordinary ”, is now a colorful minor footnote to the reckless world of the interwar years (but I remember the teenage enthusiasm with which I read Halliburton’s books while at Lawrenceville). There is a column on Halliburton in the current Lawrentian, vol. 74 no. 3 (Fall 2010). The pictures and columns above come from the archives of the ‘ Prince ’, The Daily Princetonian .

Wander in the Archives

The Archives of the Endless Bookshelf have been swept and tidied and a guide has been prepared to assist wanderers. Index would be too strong a term : the headwords tend to be suggestive rather than directive. Start here. Have fun.

This creaking and constantly evolving website of the endless bookshelf : I expect that some entries will be brief, others will take the form of more elaborate essays, and eventually I will become adept at incorporating comments or interactivity. Right now you’ll have to send links to me, dear readers. [HWW]

electronym : wessells

at aol dot com

Copyright © 2007-2010

Henry

Wessells and individual contributors.

Produced by Temporary

Culture, P.O.B. 43072, Upper Montclair, NJ 07043 USA.