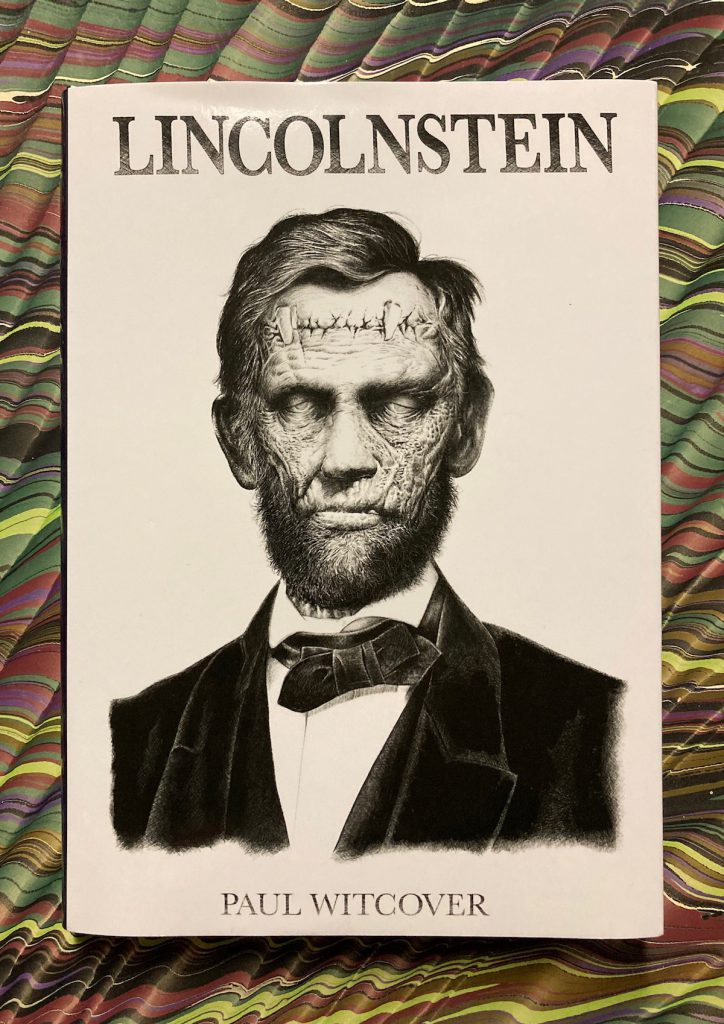

— Paul Witcover. Lincolnstein. A Novel. [Hornsea:] PS, [2021]. 155 pp. Pictorial boards, dust jacket after Carl Pugh.

Paul Witcover’s Lincolnstein is a concise and nimble critical fiction, an original and moving work expressed from the collision of historical incident and literary texts. It is a novel of ideas in motion, from the headlong rush of the kidnapping of a Confederate military surgeon by two spies from Pinkerton’s Union Intelligence Service to the shocking purpose behind their deed. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus is invoked upon the title page, but within the story the allusions emerge organically. President Lincoln has been assassinated and Stanton intends to put to use the theories of the brother of the doctor, one Victor —. “What brother? I have no brother.” is the response of the Confederate doctor who squeaks like a “Dutchman”, and yet he recognizes the apparatus assembled in the train-car laboratory. After warning, “Your President is dead […] If you loved him you would leave him that way”, the surgeon agrees, under duress, to perform the task. This conceit is bold enough, and then with the turn of a page the reader makes one more heart-wrenching discovery, and learns the other literary text with which the novel converses. Go read the book and experience it.

— — —

The resonances of Frankenstein are a stratum of bedrock, the earlier novel visible in the revulsion at the success of the process, in the flight of the monster, in the prodigious strength of the revived Lincoln and the polished oratory (Lincoln’s speeches rather than Milton’s Paradise Lost), and Mary Shelley’s novel propels the arc of the novel towards its conclusion. And yet, equally organically, the biggest and boldest of Witcover’s moves is to have Captain Finn lift the sheet from the face of another corpse in the laboratory, and in that act reveal who he is, and what his loss is. Finn’s initial disbelief yields to cold rage and he announces, “There has been a slight change of plans, Doc.”

That had been a life fit for kings. Catfish for supper, pipe always full, easy conversation all day as the shore slipped by in endless green unfurling, the river adding its voice to their own. He would have stayed there forever if he could.

A novel, like life, is motion and change, not stasis. The electricity stored in the laboratory revives the body of the president, and everything changes. Instead of the brain of the dead white bumpkin intended to render the president compliant, Lincoln’s skull now contains the brain of Jim Watson, who had been fatally wounded while helping Capt. Huckleberry Finn kidnap the doctor. Lincoln bursts from the train, and Finn pursues him, with orders from Pinkerton but with his own sense of mission. If Frankenstein impels the novel into action, the energy of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn shapes the subsequent course of events as Jim travels stealthily through the ruined landscape of war in search of his enslaved wife and children. Witcover writes short monologues, crisp vignettes of people who encounter the errant Lincoln and aid him on his way. These many supporting voices are one of the pleasures of the book.

— — —

Did you really think the Matter of America leads to a happy ending? If the legend of King Arthur is the Matter of Britain, fraud and race are the Matter of America. The other day, I came across a pamphlet on racial equality and equal suffrage from 1865, in which the pretense of America as a “white man’s country” is dismissed by the black writers of the pamphlet: “Every school-boy knows that within twelve years of the foundation of the first settlement at Jamestown, our fathers as well as yours were toiling in the plantations on James River.”

Since Pinkerton has told Finn of the Mississippi plantation where Jim’s kin are being held, Finn dogs the reanimated Lincoln’s footsteps and they soon find each other. It is not an easy reunion, and Witcover deftly brings home blunt truths, in ways Clemens could only hint at in Huckleberry Finn and in The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and the Comedy Those Extraordinary Twins (1894). Jim as Lincoln is articulate about the relations between black and white in America:

There ain’t nothing you white folks like to believe in more than the idea of your own goodness. You will ignore all evidence to the contrary, just to make yourselves feel better about all the evil that you have done or allowed to be done in your name. Sure, white folks pity a blind man. But that ain’t nothing compared to the pity you feel for the real victims of this misbegotten world: your own damn selves. It’s a story you don’t never get tired of telling, nor of hearing.

This is very direct, perhaps I have not chosen the best passage, for the discussions of Huck’s black rage and Jim’s quest are natural and seamless and the infodump is nowhere to be seen.

Jim says of his Lincoln memories, “I can feel the tug of all that was dear to him. And hateful too. Everything that touched him, for good or ill. It’s like I’m a big old spider sitting at the center of a web he spun in life.” Huck remarks on the revived president’s “steady pumping heart”, but the voice and heart of the novel are Jim Watson coming to terms with the world and the body he now inhabits.

Witcover has found the appropriate mode to convey a common usage in the world of the novel, in simply writing n——, as profanity was once elided in Victorian fiction: every one knows the word, but we don’t, can’t use it the way it was used in 1865 (or in St. Petersburg, Missouri, in 1845, or in the novel published in 1885). That is the only concession made to current discourse, and there is no evasion of the brutality of the slave system or its intertwining with American life in North or South.

In Huck and Jim’s march to the banks of the Mississippi, Witcover’s novel converses or collides with aspects of Thomas M. Disch’s Camp Concentration (the brain swap), the recent novel by George Saunders, William Faulkner, Walt Whitman, and Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”. These are not merely allusions but are integrations and transformations of that material which advance the plot and present a critical response to the precursor texts. And the key text remains Huckleberry Finn. Disguised as a blind veteran and his loyal bondsman, Huck and Jim reach Terra, the vast, prosperous De Spain plantation, which remains untouched by war and emancipation. The gross, bloated Major de Spain has made sure of his accommodations with those in power. All these elements of deceit and cozying up to power and selfishness are discernable in Clemens’ novel. The deceptions are monstrous, far more appalling than the idea of reviving the corpse of Abraham Lincoln, and the rotten structure cannot withstand the monster’s rage. And then, in a beautiful concluding passage which links both Frankenstein and Huckleberry Finn, Jim leaves the burning plantation, carrying the corpse of the person inseparable from him — just as the monster carried Victor’s corpse out into the endless Arctic wastes, so Jim lowers Huck’s lifeless body onto a timber flatboat and joins the flowing river: “The raft receded, his upright figure silhouetted in the gleam of reflected flames. Then the current took him, and he was lost in darkness.”

[HWW]