31 March current reading :

— Winsor McCay. The Complete Little Nemo 1905-1927. / Alexander Braun. Winsor McCay A Life of Imaginative Genius [2014]. Taschen, [2022].

— — —

— Raphael Cormack. Holy Men of the Electromagnetic Age. A Forgotten History of the Occult. W. W. Norton, [2025].

— — —

26 March / homeward bound

— — —

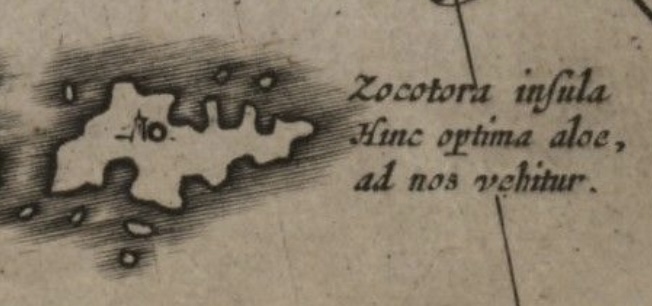

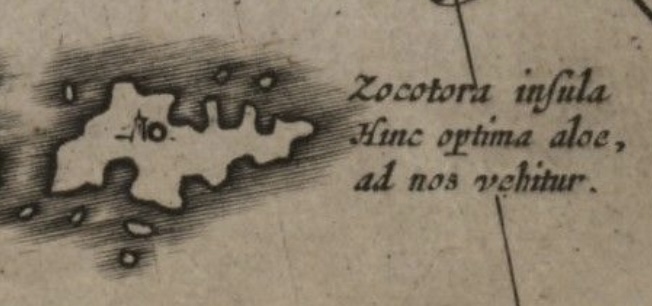

Your correspondent will be far away, and farther, and off line for the next couple of weeks, and will report upon re-entry. [Image above, Zocotora insula, detail from Turcicum imperium, in a Blaeu atlas at the Beinecke.]

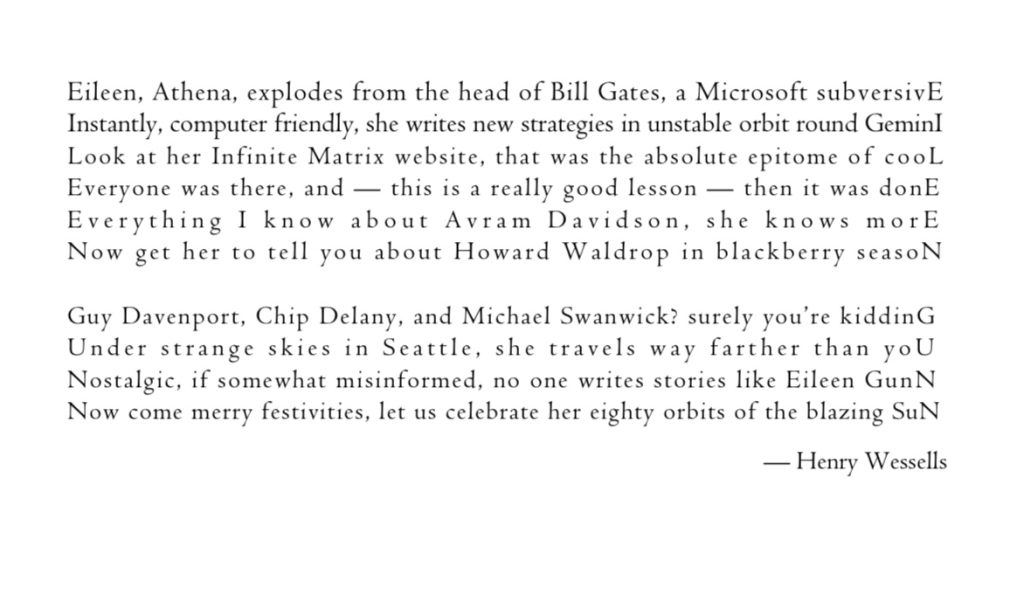

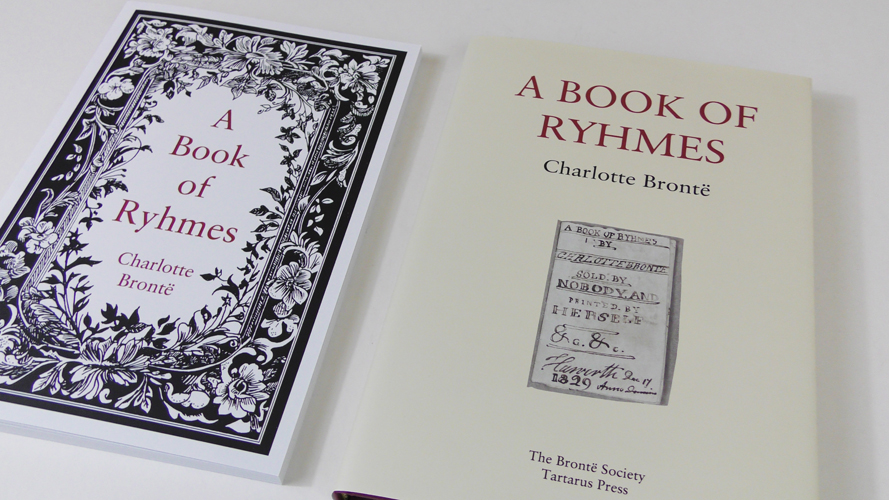

Looking ahead to April, the Brontë Society and Tartarus Press will be publishing A Book of Ryhmes by Charlotte Brontë, the manuscript book from 1829 now at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, in a fully illustrated edition with an introduction by Patti Smith, a scholarly essay by Barbara Heritage, and an afterword by Henry Wessells. Publication is scheduled for 21 April (birthday of Charlotte Brontë) and further details will be available at http://tartaruspress.com/bronte-a-book-of-ryhmes.html.

Also in April, the New York Antiquarian Book Fair will be held 3-6 April at the Park Avenue Armory. Come say hello (Cummins booth A3).

— — —

recent reading :

— John Crowley. Little, Big [1981]. Harper Perennial paperback.

Just felt like re-reading it, again.

[added note : an old and trusted friend, carried to the end of the world and back ; always something new arises from the experience of reading Little, Big]

— — —

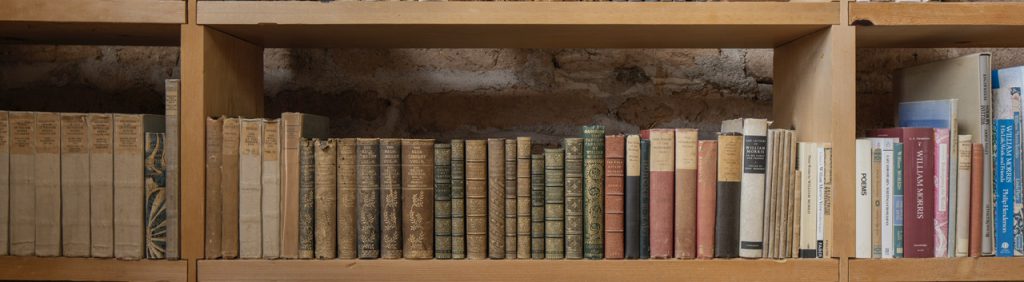

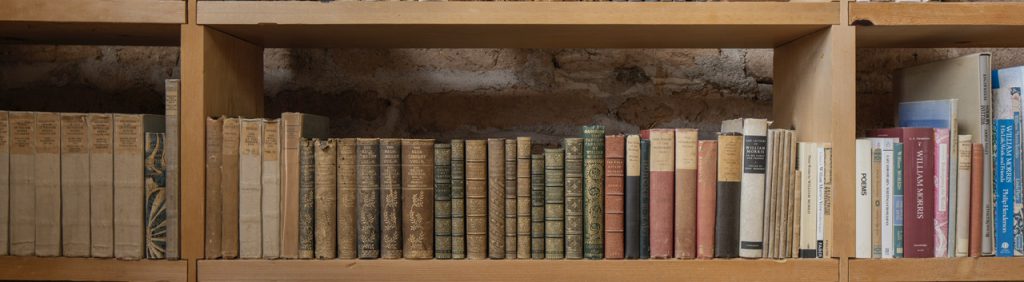

William Morris on the shelves at Chenati

The library of Donald Judd at at La Mansana de Chinati/The Block in Marfa, Texas, has been catalogued in a neat interactive (and searchable) display. When we visited back in May 2015, I remember being struck by the extent of Judd’s holdings of another artist polymath, William Morris ; the detail above shows most of those holdings. [Thanks to CB for the link.]

https://library.juddfoundation.org/#about

— — —

recent reading :

— Walter Abish. 99 : The New Meaning. With photographs by Cecile Abish. Burning Deck, [1990].

The few books I have published, however, won me no fame. I do not complain of this, anymore than I brag of it, for I feel the same distaste for the “popular author” genre as for that of the “neglected poet” (from “What Else”)

— Philip K. Dick. Radio Free Albemuth [1985]. Mariner pbk. [printed 29 Jan. 2025].

/ re-reading, though I have been thinking about “the tyranny of Ferris F. Fremont” for some time, indeed for much of the past decade

— Peter Straub and Anthony Discenza. “Beyond the Veil of Vision : Reinhold von Kreitz and the Das Beben Movement” [in:] Conjunctions 65, 2015.

— Mark D. Tomasko. Wish You Were Here. Guidebooks, Viewbooks, Photobooks, and Maps of New York City, 1807-1940, from the collection of Mark D. Tomasko. Grolier Club, 2025.

Illustrated catalogue for an exhibition on view through 10 May 2025. The Viele Topographical Map (1865) displays all the watercourses and terrain of Manhattan before the city became part of the built environment.

— — —

commonplace book :

“Elfland as implacable as ever, but now ruthlessly enmeshed in contemporary mortal affairs.” — Mark Valentine, at Wormwoodiana

https://wormwoodiana.blogspot.com/2025/03/henry-wessells-elfland-propositions.html

— — —

books received :

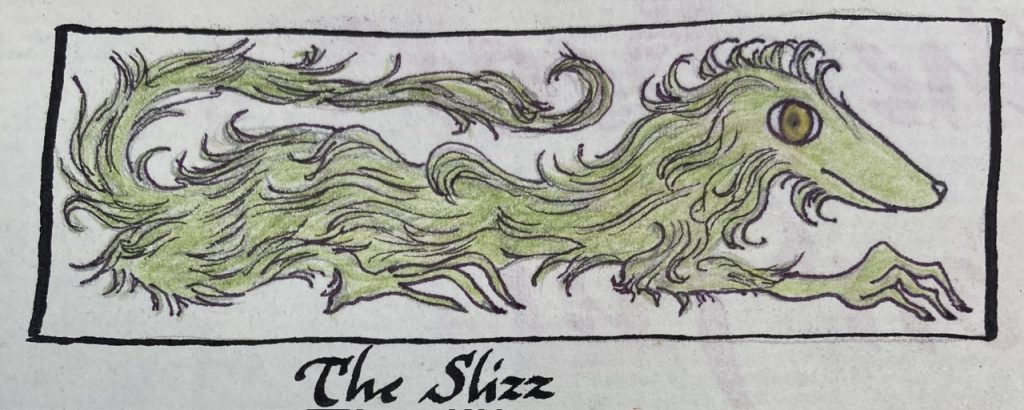

— Michael Swanwick. A Fantasist’s Guide to Venice. Dragonstairs Press, 2025. Edition of 79.

Collection of nine anecdotes about Venice, life and death, and writing, by the author of “The Mask” (collected in Tales of Old Earth).

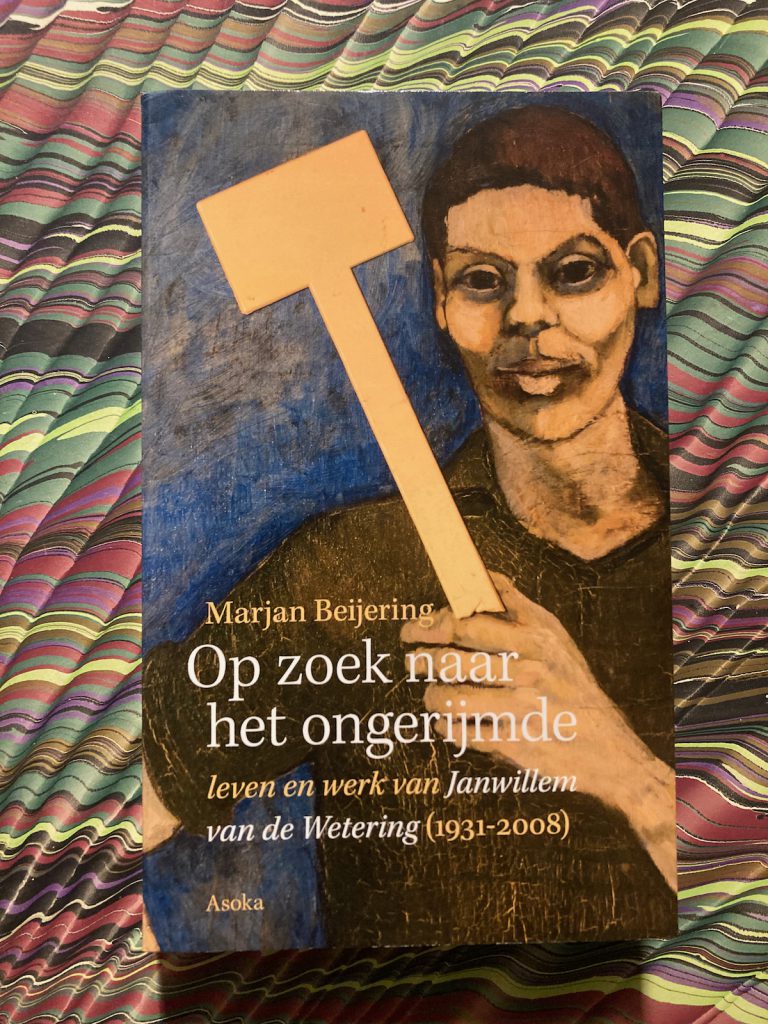

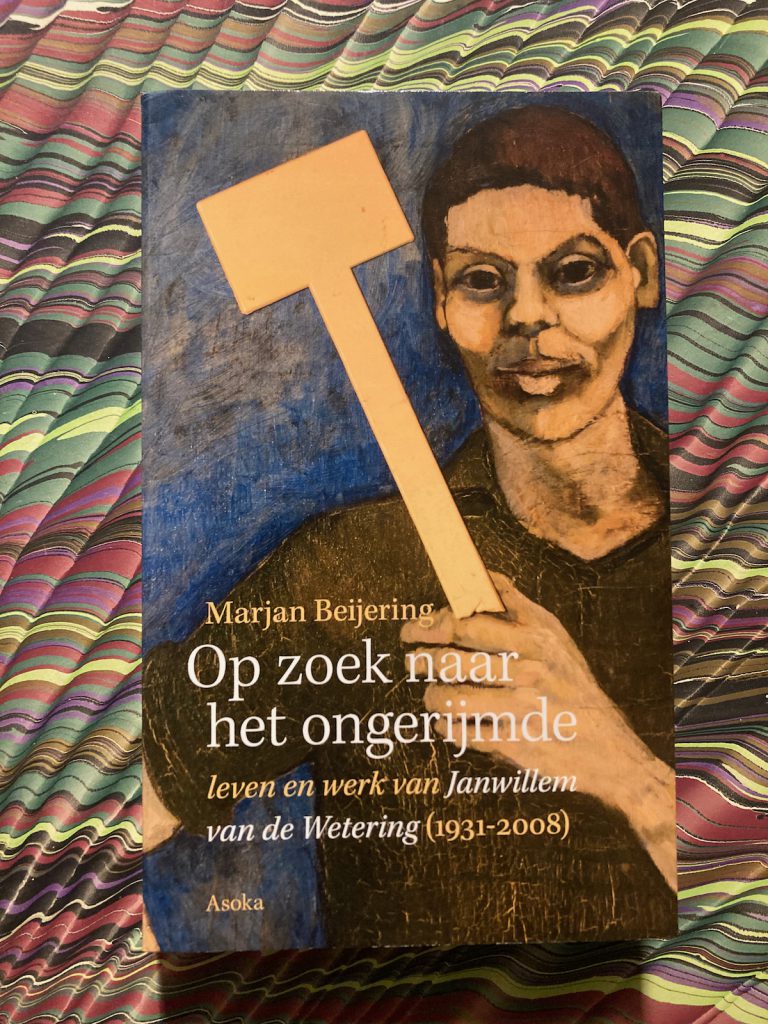

— Marjan Beijering. Op zoek naar het ongerijmde. Leven en werk van Janwillem van de Wetering (1931-2008). Asoka, [2021].

— — —

‘we are a verb, not a noun’

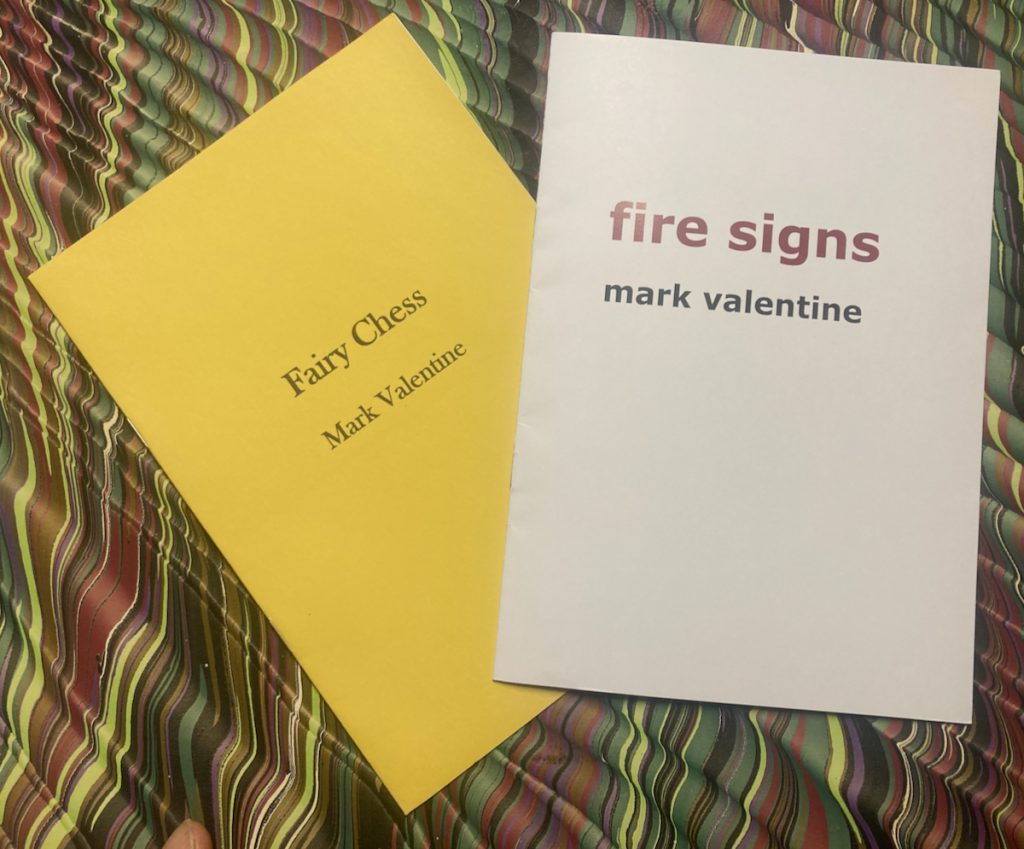

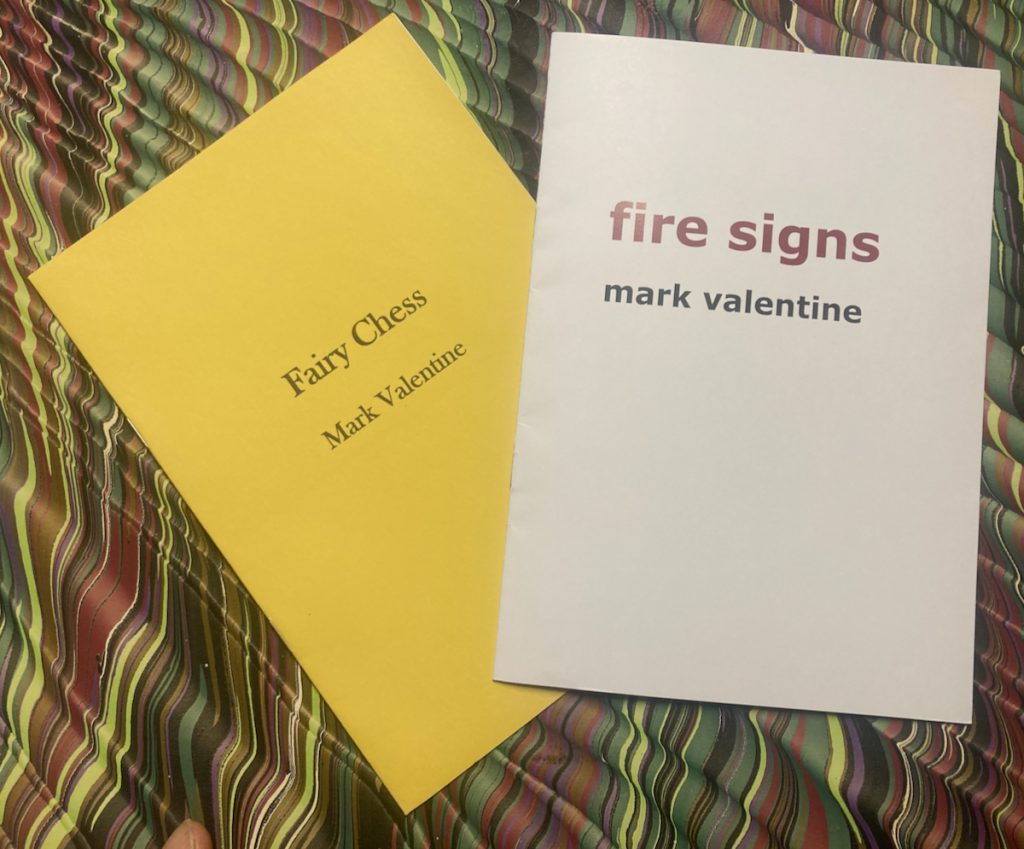

— Mark Valentine. Fairy Chess [cover title]. 2025. Edition of 100.

Collects five poems written in response to words or phrases in the work of Veronica Forrest-Thompson, with allusions to Wittgenstein, Gauloises, libraries, and bicycles.

— —. Fire Signs. [cover title]. 2025. Edition of 100.

Visual record of found poetry from Sunny Bank Mill, Farsley near Leeds.

— — —

— — —