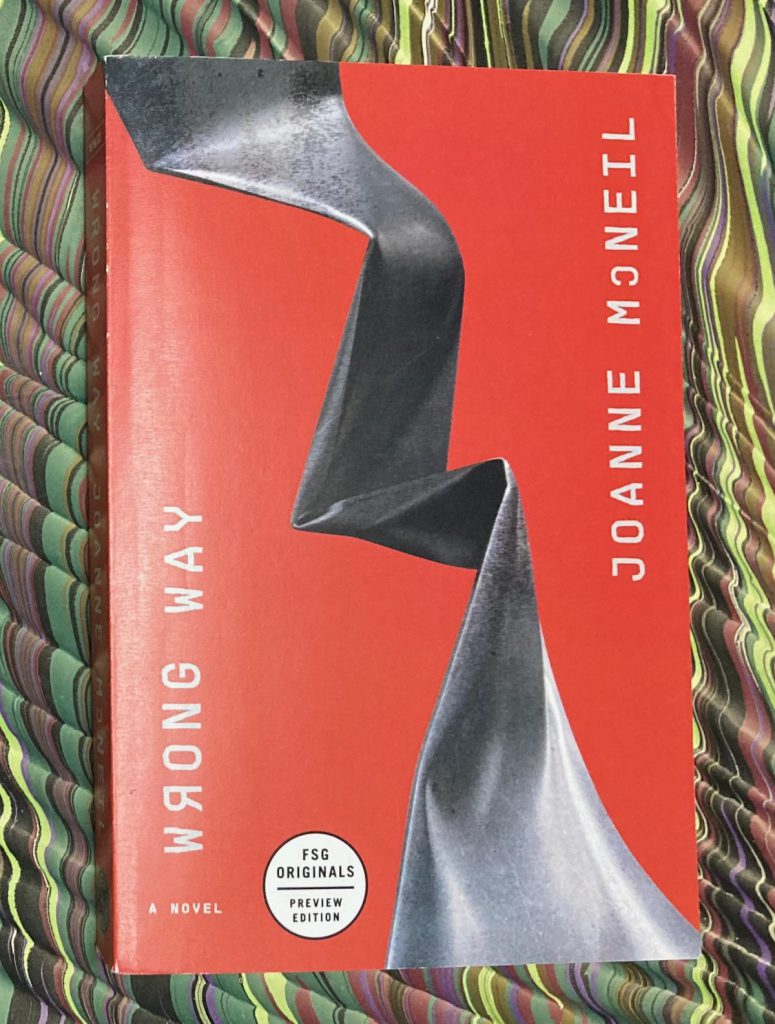

— Joanne McNeil. Wrong Way. MCD x FSG Originals, [2023].

i see things from

the under side

Don Marquis, the lives and times of archy and mehitabel

Drop everything and find a copy of Wrong Way.

This remarkable book is many things : a deep history of America through the lens of marginal employment, a social history of isolation, and an economic palimpsest of the architecture of New England mill towns. Wrong Way is the first novel by Joanne McNeil, who has a fine ear for American usages and a sneaky sense of humor evident from the first pages; her entangling memoir of technological change, Lurking. How a Person Became a User (2020) is well worth looking for. Wrong Way is a science fiction novel of the near new future, charting the life and times of Teresa Kelly, a Massachusetts woman in her late forties who swims laps the way others might jog or cycle or meditate, and who aces a virtual hand eye coordination test. “There is nothing to win,” says the recruiter, except that is never really true.

We follow Teresa in a close third-person narration that attends to small sensory details in the present and is resilient enough to sustain digressions into a litany of the jobs she has held over the years. “This could be a good job . . . ” is the voice of a pragmatic optimist and, it becomes clear, actually a pretty high bar.

The opening chapter is superb in its evocation of Teresa’s present circumstances and where she came from. Her first job as a teenager was at the jewelry counter in the showroom for an omnipresent catalogue company. “It was a good job, but those stores don’t exist now. Those jobs don’t.”

Say “Cedars” softly, without stressing the medial dental consonant.

The cognitive estrangements creep in swiftly and subtly as the shuttle bus proceeds from Boston South Station to a long-abandoned airport now repurposed as Render Falls, regional hub of the “worker first” internet company AllOver, “more than a service and experience platform”: it functions as search engine, ticketing conciergerie, payment processing, digital currency, and more. Teresa has been hired as a contract worker in the driverless car division, CR, a “transportation alternative” for top tier AllOver users. The AllOver executives — Falconer Guidry, CEO and self-made man, and Vermont Qualline, SVP of automotive engineering and daughter of a nineties country singer — have stepped from the pages of the business section of tomorrow’s newspapers, and the AllOver corporate rhetoric, ecological self-righteousness, and aspirations to a “Holistic Apex” are pitch perfect. Teresa is mature enough, and jaded enough, to be a skeptical witness, and some of the other trainee “seers” who answered the Drivers Wanted ad voice their doubts about the AllOver mission. “What kind of bottom-up change begins with people who spend fifty gs or so on an app every year?”

‘like a cockroach hiding in the kitchen walls’

The billboard in Brixboro that used to say “We Will Buy Ugly Houses” has been replaced by a picture of Plum Sasha lounging in a CR. Her teeth and blue eyes are clear and perfect. She looks carefree and young. There’s a retro eighties feel to the bubbly blue letters that read, “Luxury. Privacy. Spotless. Priceless. The CR has arrived. See it.”

Plum Sasha is an “icy-looking” teenage influencer and the advertising campaign for AllOver’s “CR driverless experience” is omnipresent. It is good advertising and pretty tough going those on the delivery side of the product. Teresa soon discovers her work as a “seer” at AllOver is not what she expected, and that things are not what they seem. On page 89, Teresa sees clearly: “It seems obvious, from the moment she sees it, but it never occurred to her earlier. Every trainee in the hangar has dark hair. There’s something else they all have in common: slim, compact bodies. It is a room of ectomorphs, each one of them about five and a half feet tall, give or take a couple of inches. Long limbs and short torsos. Bodies small enough to hide.”

At pages 110-11, things as they are become even clearer, in a “moment of weightless surrender [. . .] She is uncomfortable, still, and clings to her discomfort — once driving the CR feels natural to her is the moment she will lose control.” Coupled with the downward spiral of Teresa’s past work experiences — “The longer she worked at the museum, the more it felt like training in reverse” — this might suggest a pretty bleak book, but McNeil’s nimble prose and her eye for beauty in the mundane offer a different arc. The epigraph to this review, the refrain from “ballade of the under side” by Don Marquis, articulates my sense, from the earliest pages, that this is a novel from the economic underside of the American tech miracle. And so it was a small pleasure to see the simile “like a cockroach hiding in the kitchen walls” at page 119, part way into into the narrative drive. For drive it is: Wrong Way threads and weaves through the greater Boston area with a sureness of inborn knowledge — I have visited many times and still have no clues as to how Cambridge and Boston and the Charles River are braided together.

‘Route 128 when it’s dark outside’

We read and write on analog paper, and we read and write on electronic paper. We live in a world where the analog and the digital reciprocally permeate each other; we are hybrids, and so are our media.

Lothar Müller, Weiße Magie / White Magic, The Age of Paper (translated by Jessica Spengler)

Science fiction demands that metaphor be taken literally. Wrong Way is a science fiction novel about the hybrid nature of work in the twenty-first century. Teresa puts herself — contorts herself — into her job in a way that employers take to the bank. Capitalist systems are designed for economic returns with little heed for the human costs. “When things are good with work, all it means is, things will get worse.” The soundtrack to Wrong Way might well include “Roadrunner”, Jonathan Richman’s paean to the highway late at night, Route 128 when it’s dark outside, just before a tech boom that forms part of the geologic past of Wrong Way. The brief moments of camaraderie with fellow seers or with truck drivers are nicely done yet serve only to highlight a chronicle of isolation. I don’t want to leave the wrong impression: Wrong Way is a novel that addresses serious topics with flashes of wit and wild imagination. McNeil takes the reader to strange places. And just what happens in the last two chapters will be a matter of personal interpretation. I can’t wait to discuss it with other readers.

Drop everything and find a copy of Wrong Way. It’s an engaging and provocative work, the best book I’ve read this year.

The Endless Bookshelf book of the year 2023.