recent reading : early june

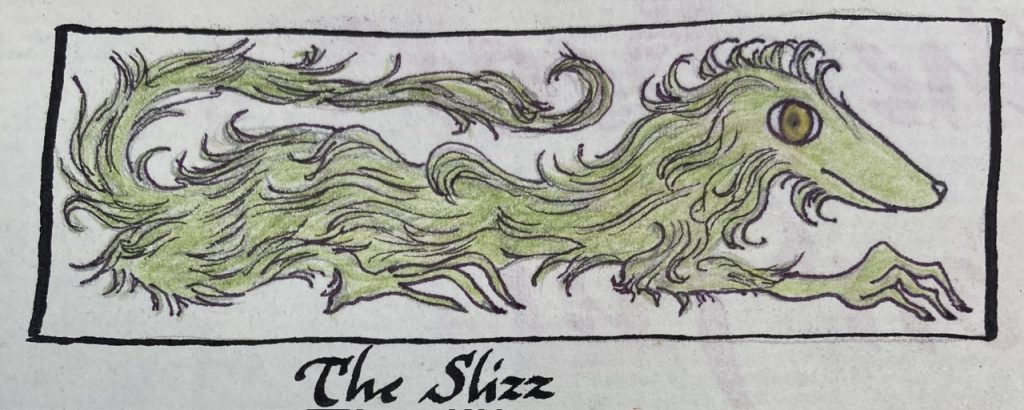

— Tom LaFarge. The Crimson Bears. Part I. Sun & Moon Press, [1993].

——. A Hundred Doors. The Crimson Bears. Part II. Sun & Moon Press, [1994, i.e., 1995].

/ I have loved The Crimson Bears ever since I first encountered them, I read read them aloud to the offspring, and wrote about them, and about the early career of Tom La Farge (1947-2020) here : https://endlessbookshelf.net/bargeton.html

Am re-reading these in advance of the re-issue by Tough Poets Press. This is fabulous news !

— Paul McAuley. War of the Maps [2020]. VG [Gollancz], 2021.

/ what a writer ! McAuley makes it happen. Everything is otherwise but there are echoes & riffs of Beckett early on, and I see everywhere threads of Le Guin (The Dispossessed, in particular) ; and now, far out in the world ocean, a glimpse by the lucidor protagonist of world wanderers (an albatross by any other name) conjures up all the ripples of Coleridge ; and the deployment of Chekov’s dictum is deft and sudden. McAuley’s unexpected turns are shocking, deeply satisfying, the work of a magician who sets up his effects with precision and perfect timing.

— — —

this just in

— Brendan C. Byrne. Another World Isn’t Possible. Stories. 226, [4], [6, ads], [3, blank], [1, imprint] pp. [Melbourne :] Wanton Sun, [2025 : POD, Chambersburg, Penna., 5 June]. Cover by Matthew Revert.

/ I know a few of these stories (even published one), but wow ! have I been looking forward to this collection. Stylish design !

/ from the blurbs : “Ruthlessly hip, transreal surreal. Worth your time.” — Rudy Rucker

— — —

various :

— Brian Eno and Bette Adriaanse. What Art Does. An Unfinished Theory [2024]. Faber, [2025].

/ serious, playful thinking about the what and why of art.

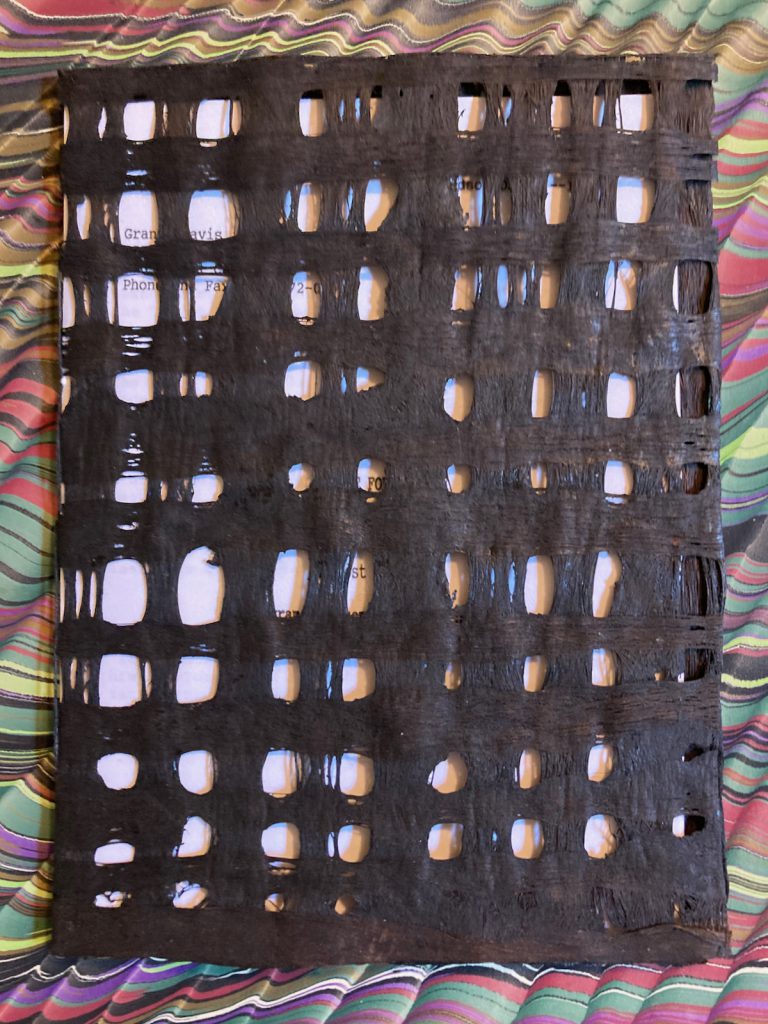

/ the Endless Bookshelf reminds readers of the Humument fragment by Tom Phillips, “the reader is the artist” :

https://temporary-culture.com/conversation43e/

— Colin Wilson. Jorge Luis Borges. Cover with portrait drawing by Hugo Manning. London : Village Press, 1974.

/ literary journalism by Colin Wilson, reductive in tone, and in the end more interested in himself than in the writings of Borges

— John Shen Yen Nee and S J Rozan. The Railway Conspiracy. Soho Crime, [2025].

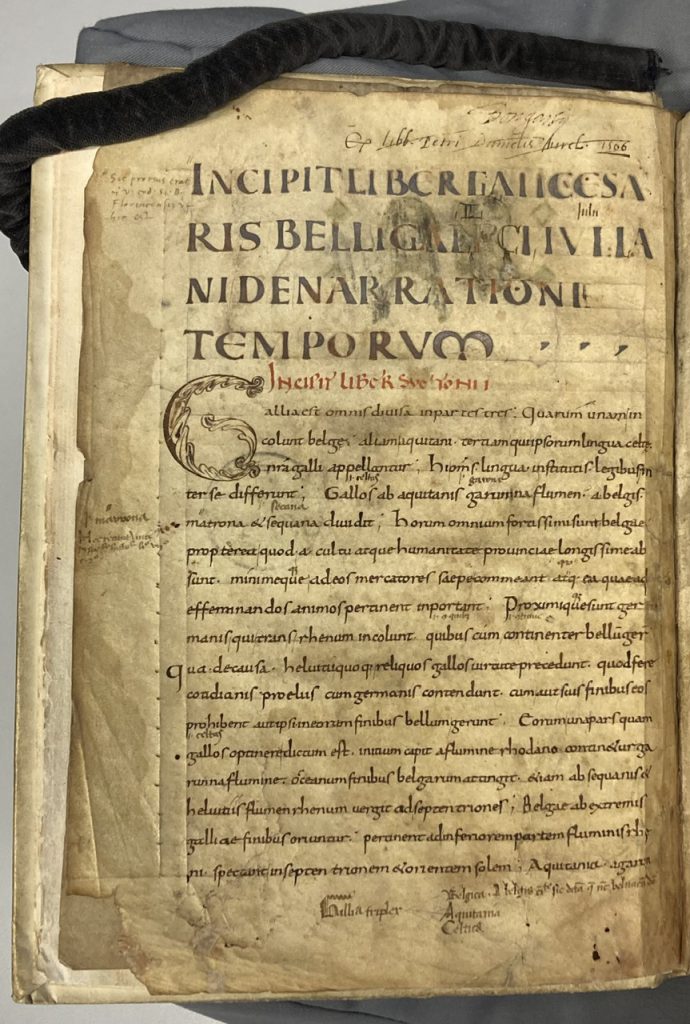

— William S. Reese. The Best of the West. 250 Classic Works of Western Americana. William Reese Company, 2017.

/ succinct illustrated discussion of books (1555-1941) that chart the exploration and settlement of the American West.

— — —

— Mark Hanusz. Kretek. The Culture and Heritage of Indonesia’s Clove Cigarettes. [With a foreword by Pramoedya Ananta Toer]. Illustrated in color throughout. [xx], 203 pp. Equinox Publishing, 2000.

/ heard about this from a new acquaintance who grew up in Indonesia and described the sensory rush of memories arising, years later, from finding a discarded packet of clove cigarettes. Never smoked them myself but the olfactory memory is there. Bought two copies, one for a friend interested in the history of smoking and related phenomena.

— — —

— Heiress. Sargent’s American Portraits. 16 May – 5 October 2025 [Cover title]. [Foreword by Richard Ormond]. English Heritage | Kenwood, 2024.

/ Catalogue of an exhibition of 18 portraits by John Singer Sargent, with summery biographies of the American heiresses who married into the British inner circles and aristocracy. An excellent, compact show. Ormond is author of the Sargent catalogue raisonné.