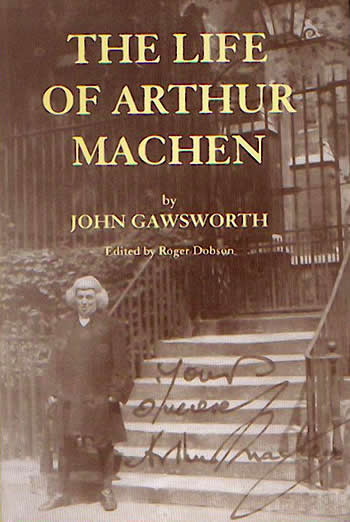

In 1923, a century ago, Welsh author Arthur Machen was at the height of his literary reputation on both sides of the Atlantic. It had been a long path from his “horrible” juvenile poem Eleusinia (1881) and such early books as The Anatomy of Tobacco (1884) and the numerous translations of the 1880s and early 1890s. But with The Great God Pan (1894) and The Three Impostors (1895), Machen produced a small group of supernatural tales that shocked upon their first appearance and then proved to be enduring. The other great work written in the late 1890s, The Hill of Dreams, Machen’s “‘Robinson Crusoe’ of the soul” depicting the aesthetic visions of young Lucian — and the tensions between pastoral and urban life — remained unpublished until 1907. Literary success was never easy for Machen and indeed he spent an interval as an actor with a provincial repertory company before returning to literary journalism and newspaper work, during which he created a modern myth of the first world war, The Bowmen. This is the barest outline of Machen’s career, and more detailed accounts can be found in Mark Valentine’s 1995 monograph or The Life of Arthur Machen, John Gawsworth’s biography (begun during Machen’s lifetime but published only in 2005). But that is to get ahead of things.

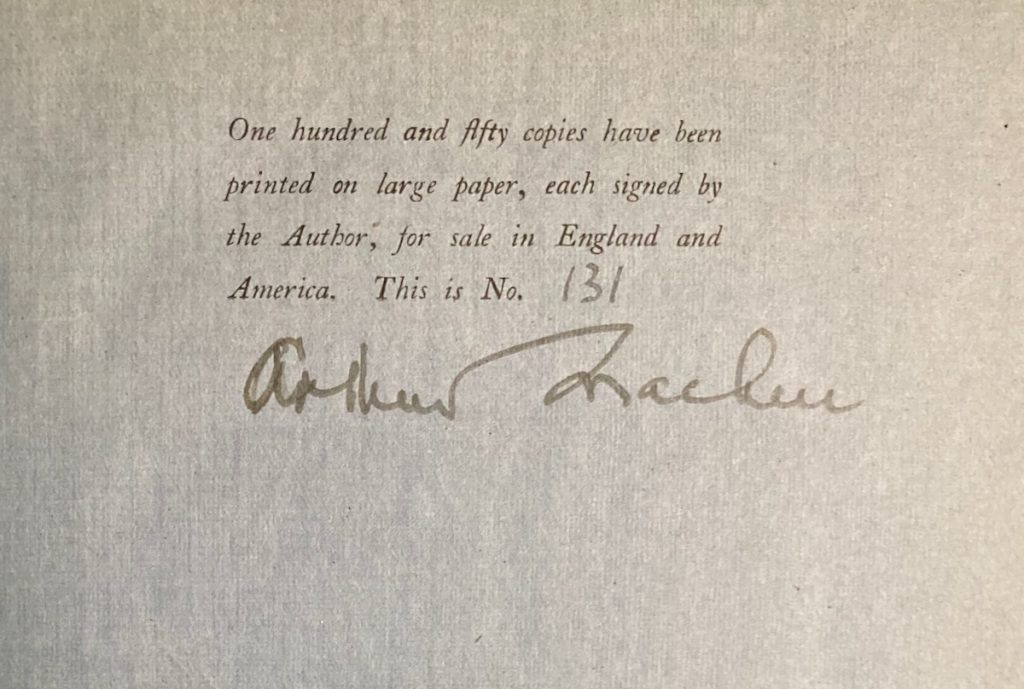

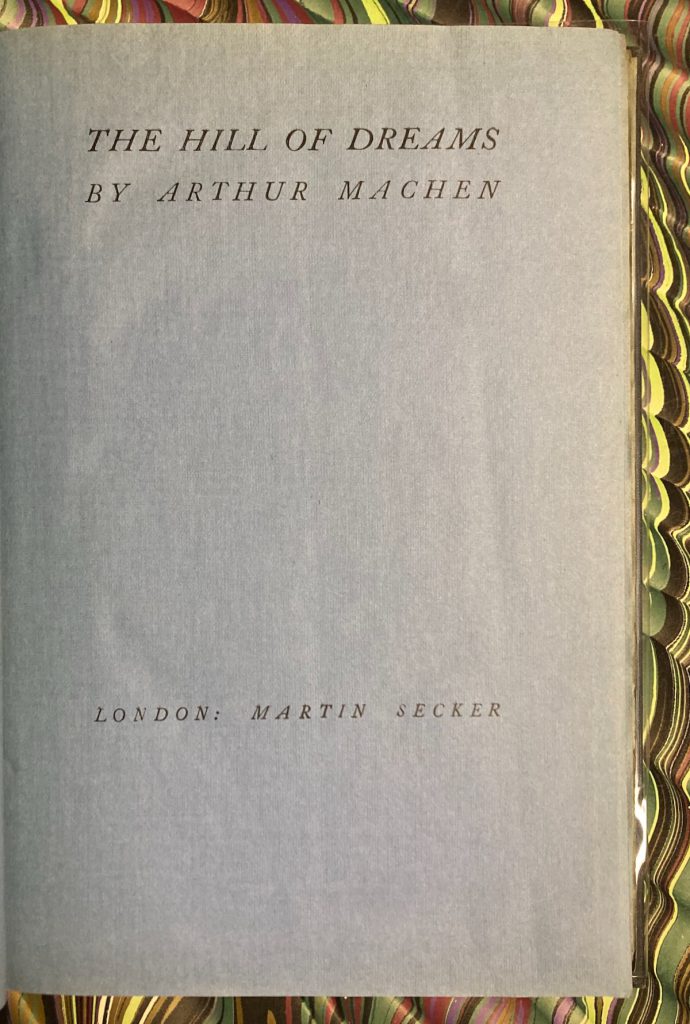

In 1923, Machen had many books in print: the year before, his edition of the Memoirs of Jacques Casanova (1894) had been reprinted in twelve volumes, and Far Off Things, a collection of wartime columns from the London Evening News, entitled “Confessions of a Literary Man” and recounting his hard apprenticeship in the 1880s and early 1890s, had been published. In 1923, his London publisher, Martin Secker, brought out another volume of autobiography, Things Near and Far, and a new work of fiction, The Secret Glory, as well as a signed large paper edition of The Hill of Dreams (the latter on blue paper, illustrated at top and below). In 1923, Henry Danielson published a Bibliography of Machen’s works through 1922, with retrospective “annotations” on each work by Machen, and with a deluxe issue signed by Machen. Secker published the Caerleon Edition of the Works of Arthur Machen in nine volumes dated 1923; in New York the enterprising Alfred A. Knopf brought out an attractive series of Machen’s books: The Hill Of Dreams, The Three Imposters, Far Off Things, The House of Souls, Things Near and Far, and Hieroglyphics; with others to follow in 1924: Dog and Duck, Ornaments in Jade (signed by the author), and The London Adventure. It really was peak Machen.

What else was going on at this time? It’s useful to look at Machen in the context of other books published and contemporary literary currents around 1923. One notable work of fantasy was William M. Timlin’s The Ship That Sailed to Mars, illustrated by the author; lush and imaginative, it had little in common with Machen’s themes. The Club Story and the told tale showed itself alive and well with Sapper’s The Dinner Club; and master of the uncanny Algernon Blackwood published his curiously incomplete autobiographical work, Episodes before Thirty. Aleister Crowley’s The Diary of a Drug Fiend was fiction rooted in the author’s own experience: transgressive, but again in a manner unlike Machen’s. If Ornaments in Jade, Machen’s sequence of prose poems, seems almost a harbinger of modernism, such was the conservatism of English letters that it is to the early modernism of Baudelaire that these point.* When one considers works such as Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) and Hemingway’s Three Stories and Ten Poems (1923) and the sudden emergence of the modernist aesthetic (in both minimalist or encyclopedic modes), it becomes quickly apparent that Machen achieved his greatest popularity at a moment when the world changed. “By the time he was rediscovered in the 1920s he was near retirement and no longer capable of producing high-calibre material” (SFE). This position of being somewhat at odds with the dominant modernism points to an explanation of the near obscurity of Machen’s work well into the 1980s when a revival of interest in the writings began, with the formation of an Arthur Machen Society, and later the Friends of Arthur Machen.

As a bookseller, I had three Machen items of great interest, sold long ago: the manuscript of his late essay “The True Story of the Angels of Mons” (1938); an extended autograph quotation from The Hill of Dreams (almost certainly written out for a collector in the mid 1920s); and a signed photograph of Machen in costume as Doctor Johnson from a film shoot circa 1922, which was reproduced as the dust jacket illustration when the Friends of Arthur Machen and Tartarus published The Life of Arthur Machen. His is a household name only within the literature of the fantastic now, but the books are more readily available and sometimes read. Machen’s work is always worth exploring.

* In fact, as I learn from reading The London Adventure, the prose poems of Ornaments in Jade were written in the 1890s, more or less at the same time as The Hill of Dreams.

* In fact, as I learn from reading The London Adventure, the prose poems of Ornaments in Jade were written in the 1890s, more or less at the same time as The Hill of Dreams.