current reading :

— Marcel Proust. Albertine disparue [1925]. Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

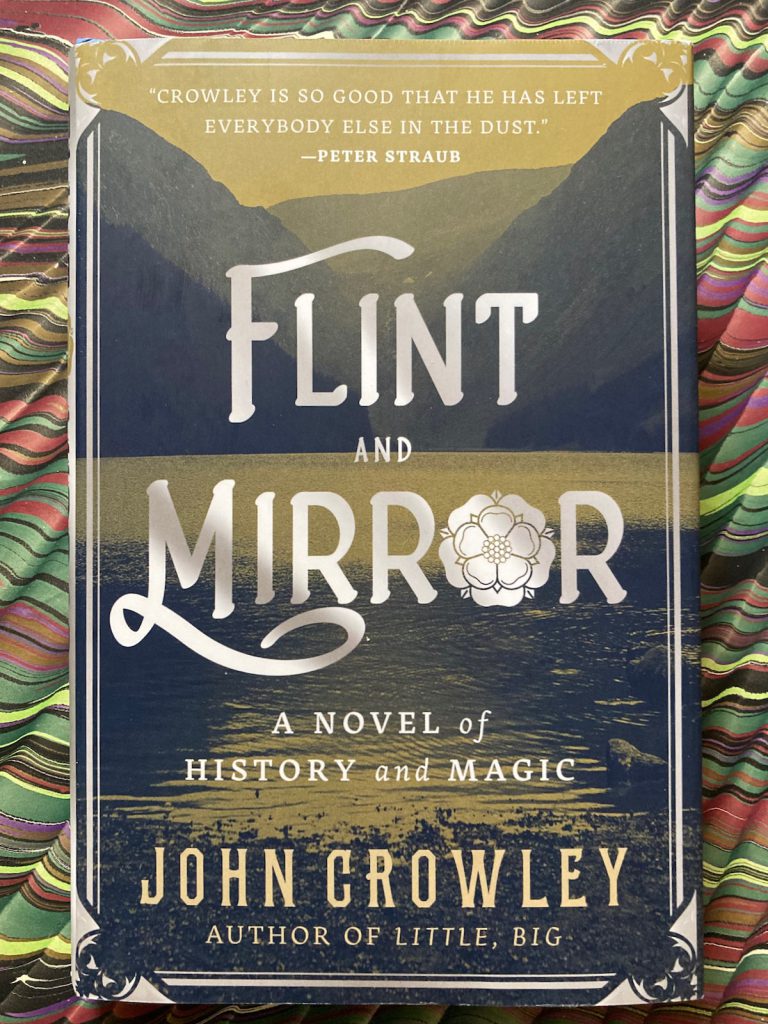

— C. P. Curran. James Joyce Remembered. Edition 2022. With essays by H. Campbell, D. Ferriter, A. Fogarty, M. Kelleher, H. Solterer. Collection presented by E. Roche & E. Flanagan. Illustrated. x, 224 pp. UCD Press, 2022.

— — —

recent reading :

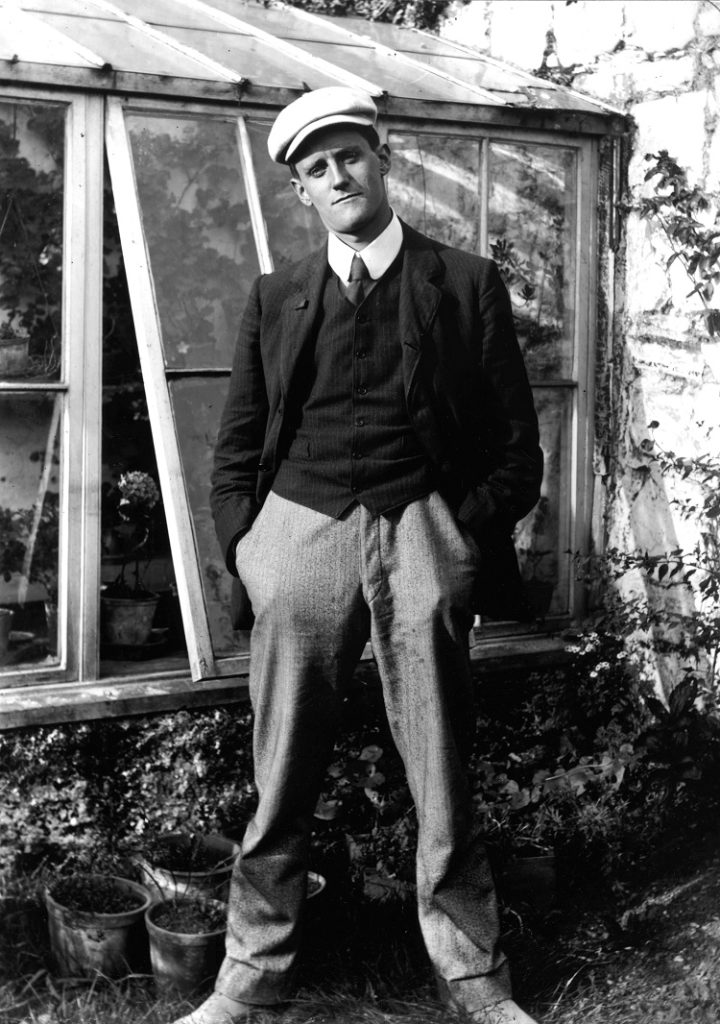

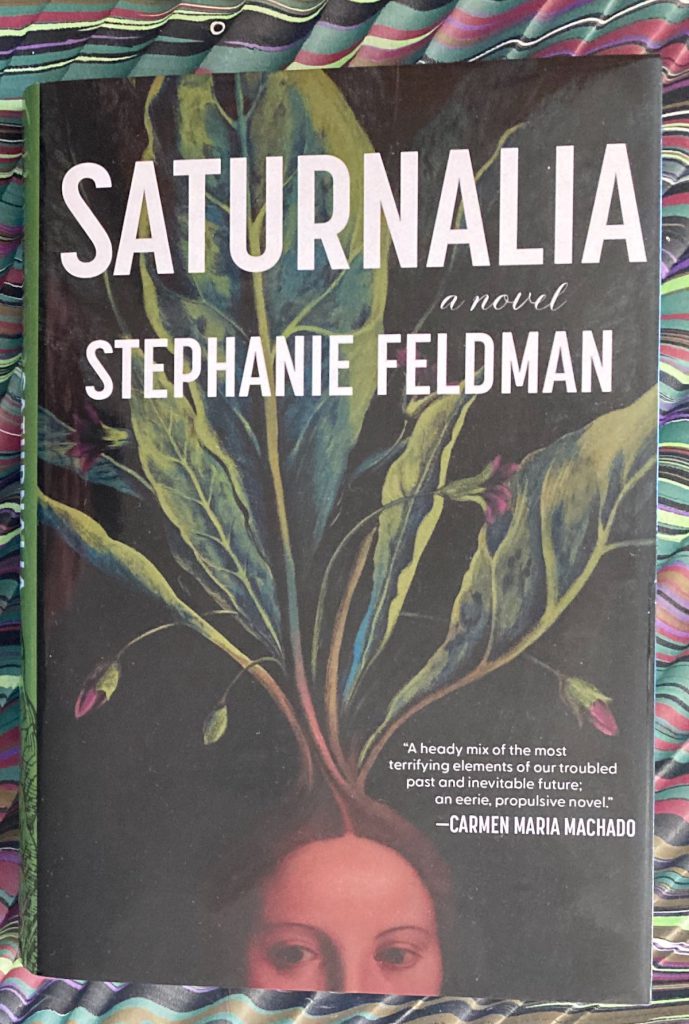

— Stephanie Feldman. Saturnalia. A Novel. Unnamed Press, [2022]. A dark celebration of the mysteries in the streets of a Philadelphia shattered by climate change, epidemics, and political manipulations. Not since In the Drift by Michael Swanwick has the threatening power of the city’s social clubs been summoned so palpably. Though the novel treats with matters of alchemy and magic, the narrative strategy is strongly anchored in mimetic realism.

— George Sims. The Rare Book Game. Holmes Publishing Company, 1985. Collection of essays by English bookseller and mystery novelist George Sims. With the companion volumes, More of the Rare Book Game (1988) and Last of the Rare Book Game (1990). Sims had remarkable access to archives of A. J. A. Symons, Oscar Wilde, Eric Gill, and others, and his discussion of the authors and the materials he handled makes for fascinating reading.

— — —

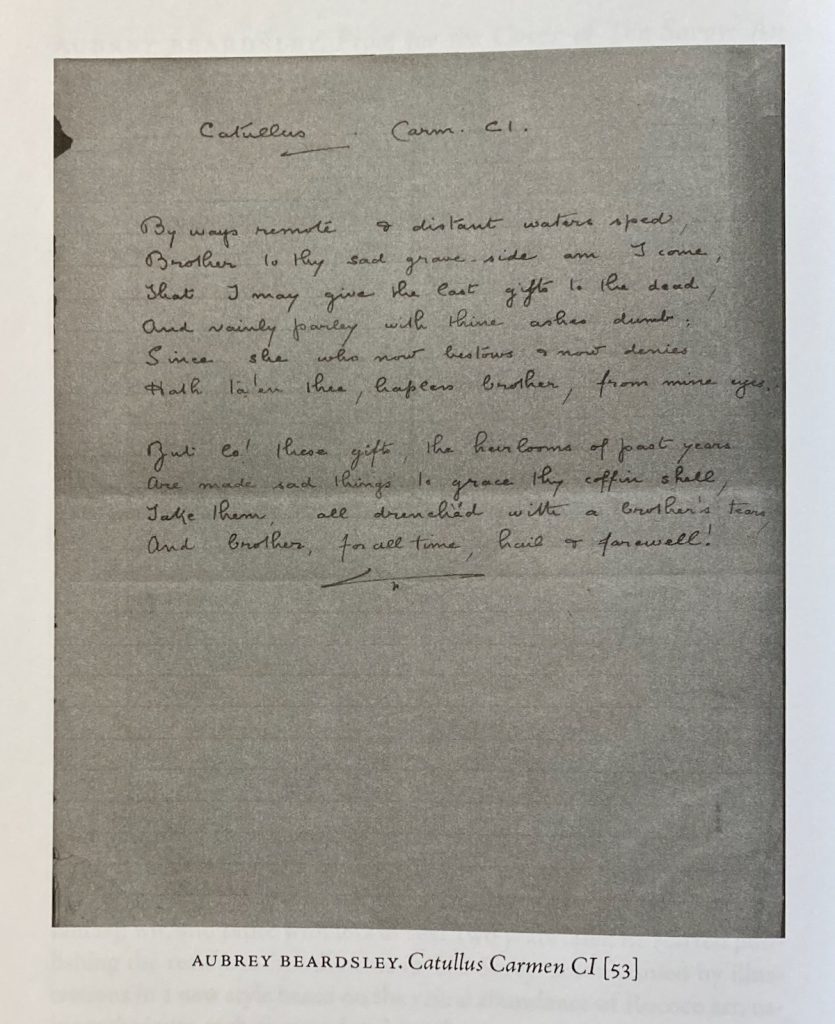

— Margaret D. Stetz. Aubrey Beardsley 150 Years Young. From the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. 44 illustrations, 69 items. 85 pp. Grolier Club, 2022. Excellent record of the fabulous, witty, and nimbly erudite descriptive labels from the Beardsley exhibition (8 September to 12 November 2022). The translation from Catullus illustrated above suggests that a classical education was not without its rewards. Not being a Latinist, your correspondent is glad that Beardsley could knock out such a poem.

— Margaret D. Stetz. Aubrey Beardsley 150 Years Young. From the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. 44 illustrations, 69 items. 85 pp. Grolier Club, 2022. Excellent record of the fabulous, witty, and nimbly erudite descriptive labels from the Beardsley exhibition (8 September to 12 November 2022). The translation from Catullus illustrated above suggests that a classical education was not without its rewards. Not being a Latinist, your correspondent is glad that Beardsley could knock out such a poem.

— Rick Moody. Surplus Value Books. Catalog Number 13. Illustrated by David Ford. Unpaginated, [40] pp. [Santa Monica]: Danger Books!, [2002]. Edition of 174 copies signed by the author. An acerbic jeu d’esprit, a pitch perfect catalogue of imaginary books compiled by an obsessive romantic stalker. Originally published in wrappers in different format in 1999.

— Adam Roberts. The History of Science Fiction. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

— George Pelecanos. The Night Gardener. Dennis McMillan, 2006.

— Marcel Proust. La Prisonnière [1923]. Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. I have been reading my way through Proust for the last year, slowed down but still going. One thing that has emerged, to my surprise, is how funny the narrator is at times.

— — —

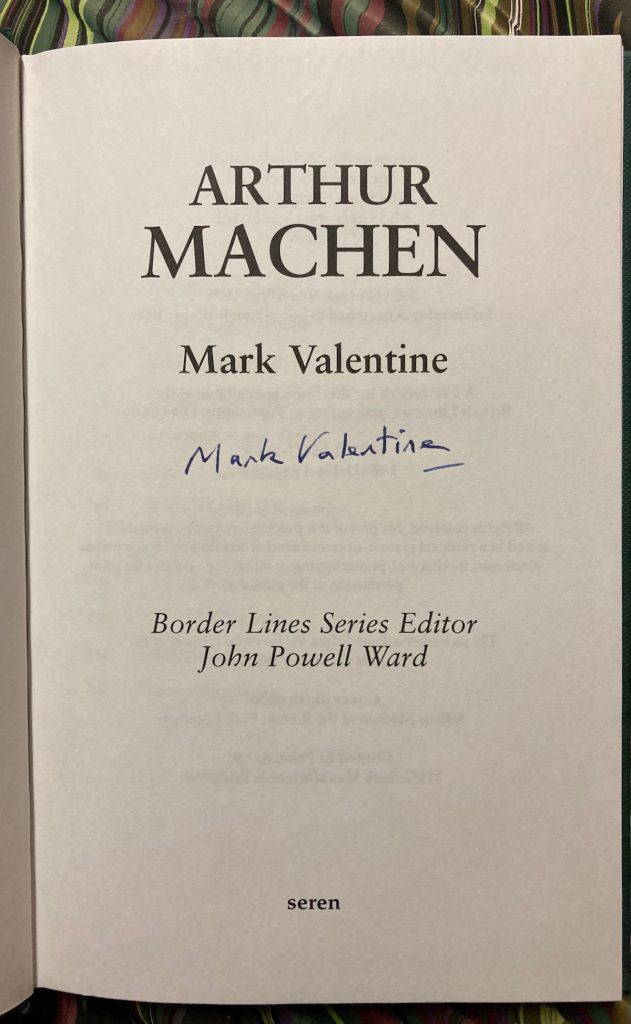

— Mark Valentine. Arthur Machen. Seren, [1995]. Concise biography with an excellent account of the Gwent landscapes of Machen’s youth and their influence upon him.

— Kij Johnson. The River Bank. A sequel to The Wind in the Willows. Illustrations by Kathleen Jennings. Small Beer Press, [2017].

— — —

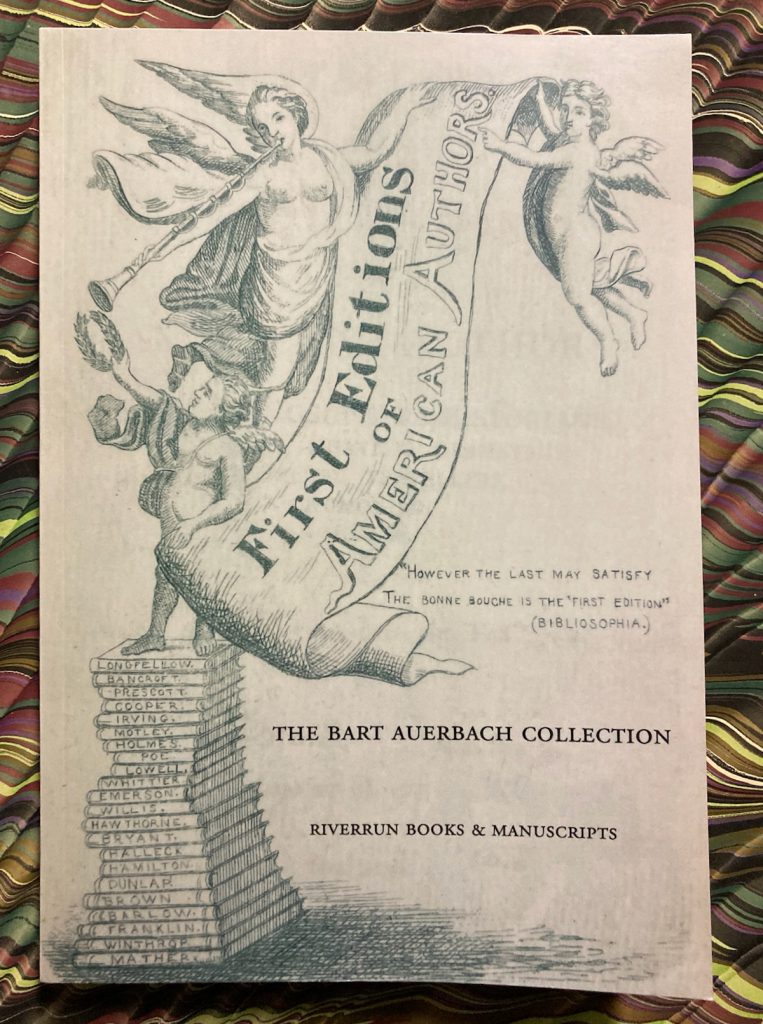

— The Bart Auerbach Collection. Dedication Copies; Books, Letters & Manuscripts; The Book Trade; Poets, Philosophers, Historians, Statesmen, Essayists, Dramatists, Novelists, Booksellers, Humorists, &c., &c., &c. Riverrun Books, [2022]. An illustrated memorial catalogue of the private collection [500 items] of the dean of New York antiquarian book appraisers.

— — —

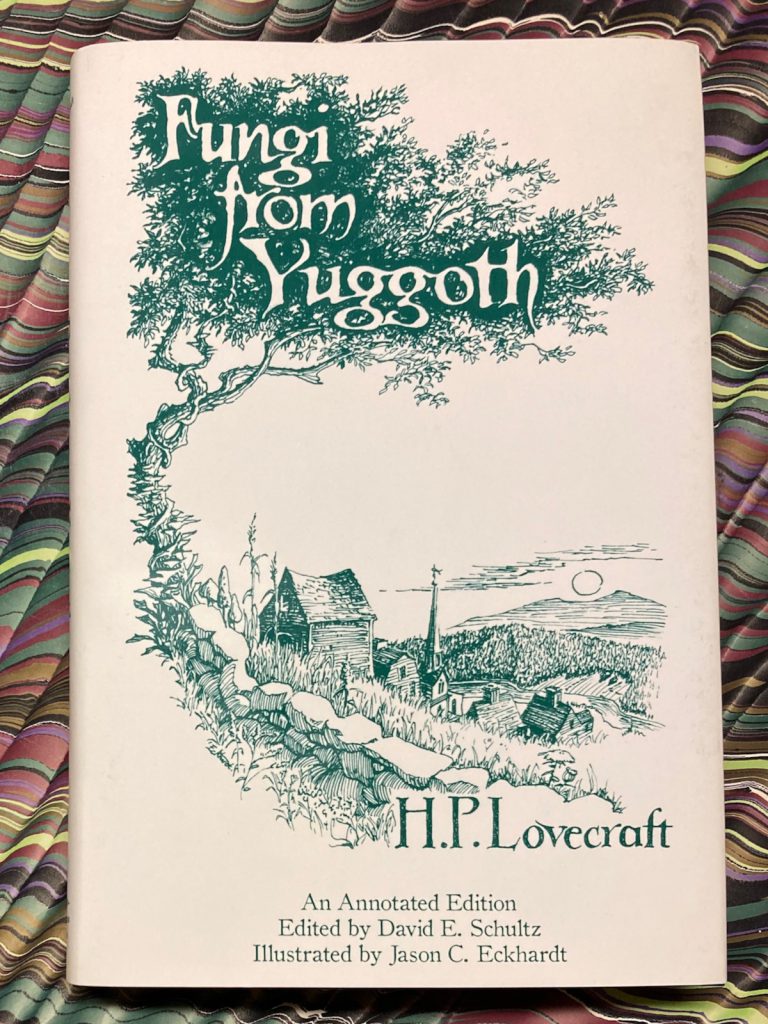

— H. P. Lovecraft. Fungi from Yuggoth. An Annotated Edition. Edited by David E. Schultz. Illustrated by Jason Eckhardt. Hippocampus Press, [2017]. [re-read].

— Francis Brett Young. Cold Harbour. Collins, [3rd ptg, 1926].

— Giuseppa Z. Zanichelli. I codici miniati del Museo Diocesano “San Matteo” di Salerno. Lavegliacarlone, 2019.

— Curzio Malaparte. The Skin. [La Pelle, 1949]. Translated from the Italian by David Moore. Introduction by Rachel Kushner. NYRB paperback.