‘a Bloomsbury ghost story’

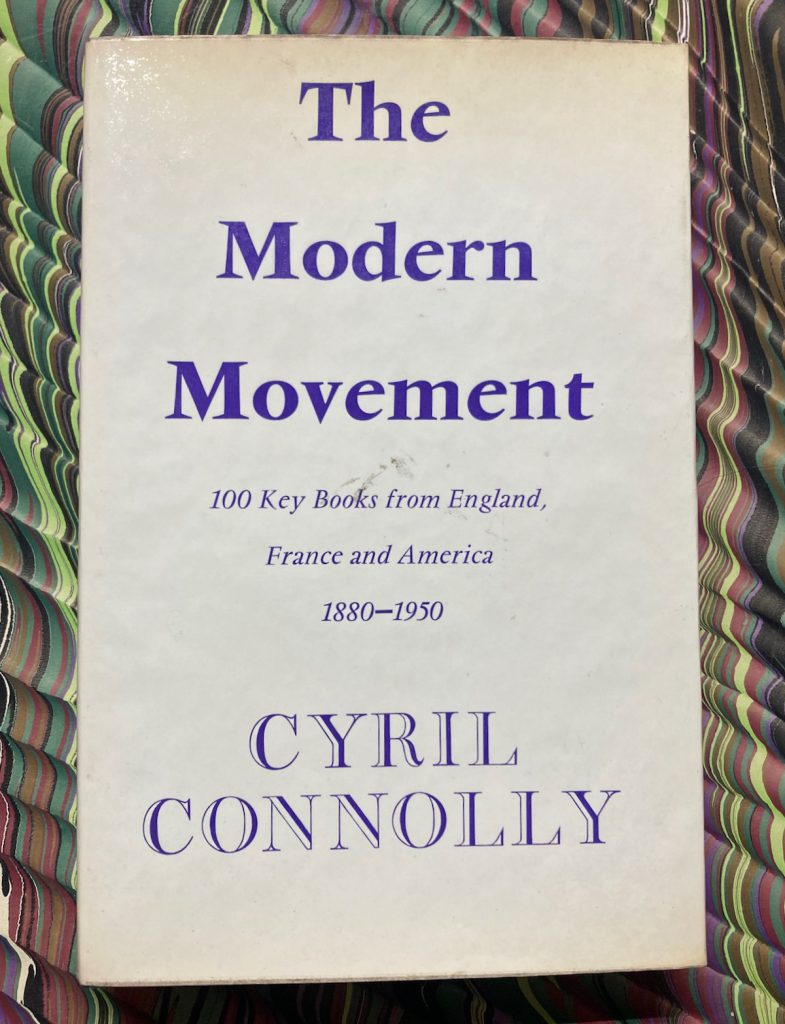

This month marks sixty years since publication of The Modern Movement 100 Key Books from England, France and America 1880 – 1950 by Cyril Connolly and the anniversary prompted me to look into my copy again, to see how many titles from this perpetual argument I have read. There are a few clippings from contemporary reviews in London newspapers tucked in the back, with comments ranging from bilious persnickety objections about the “crazily unsuitable title for such a very personally conducted excursion” (Tour d’Horizon, in the Times Literary Supplement for 23 December 1965) to complaints of omission of works from central and eastern and southern Europe (let alone non-western literatures !). The funny thing about this “kind of Michelin Guide to the 100 key resorts of modern literature” (Anthony Curtis, Knocking up a Century, in the Sunday Telegraph, 12 December 1965)* is that all of the praise and criticisms of the book are still true, and the passage of time has made the omissions only more evident.

And yet it does not matter. “Connolly’s list had to be judged within his own terms of reference. They were meticulous” (Oliver Edwards, Talking of Books, in the Times, 9 June 1966). He did not aspire to universality : his hundred comprises books in English and French (languages Connolly read with facility) and constituting “a revolt against the bourgeois in France, the Victorians in England, the puritanism and materialism of America.” Some of the choices seem at first glance a bit old-fashioned and nostalgic in 2025 (“Nostalgia, nostalgia” was a complaint of reviewers at the time), but when reading Connolly’s summaries and the context he offers, the relevance becomes clear.

Any list is an invitation to argument, of course, that is half the fun. Attempts to define a canon by their very nature invite readers to form their own opinions, to determine positions of resistance or opposition, and to propose alternative or transgressive views. There is long tradition of these lists of key or influential works in literary history and in collecting : think of the Grolier Club hundreds in English and American literature, science, medicine, typography, and children’s books. In the category of superlatives, there have been Best Book hundreds in science fiction, fantasy, and horror (the Horror volume edited by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock elicited some very acute contributions from contemporary writers). Even in adhering strictly to 100 titles, Connolly still manages to cram in allusions to dozens of other “key” writings from Leaves of Grass and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to Sartre (H. R. F. Keating did much the same in his detective fiction hundred).

— The Modern Movement 100 Key Books from England, France and America 1880 – 1950. Chosen by Cyril Connolly. Bibliography of English and French editions [by] G. D. E. Soar. Andre Deutsch | Hamish Hamilton, [1965].

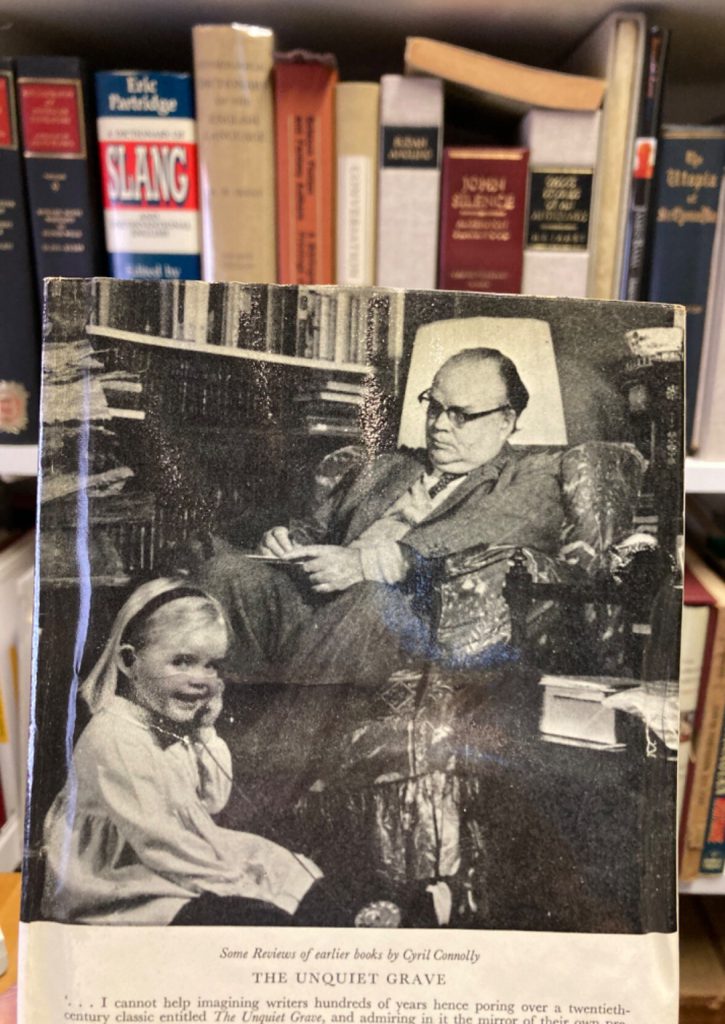

Back cover photo of The Modern Movement by Otto Karminski, 1965. [What the hell is going on there ?]

— — —

In “Apotheosis in Texas”(Sunday Times, 6 June 1971) Connolly recalled how his book was “marred by misprints, savaged by critics and immediately followed up by a polymath compendium which included scientists and film stars as if to prove how mine should have been done. Only in booksellers’ catalogues did my own selection and phrasing — fruit of years of love and worry — begin to make headway.” No surprise, really, lists are useful for collectors as well as for readers and booksellers — and the ambivalence of academic critics was water off a duck’s back to him, particularly after 1971, when the Humanities Research Center of the University of Texas at Austin, mounted an exhibition of books and manuscripts based on Connolly’s hundred, The illustrated catalogue continues to dazzle, with manuscripts, inscribed books, letters, and more.

— Cyril Connolly’s One Hundred Modern Books from England, France and America 1880 – 1950. Catalog by Mary Hirth with an introduction by Cyril Connolly. An Exhibition : March – December 1971. The Humanities Research Center – The University of Texas at Austin, [1971].

— — —

* Curtis has one of the best observations about The Modern Movement : “Anyone who thinks it is impossible to say anything significant in under 800 words ought to read some of these brilliant compressions ; if this is ‘instant criticism”, let us have more of it.”

And I still have a fair bit of reading to do.

— — —