31 January 2025

in today’s mail

— Conjunctions 83. Revenants : The Ghost Issue. Edited by Bradford Morrow and Joyce Carol Oates. Bard College, 2024.

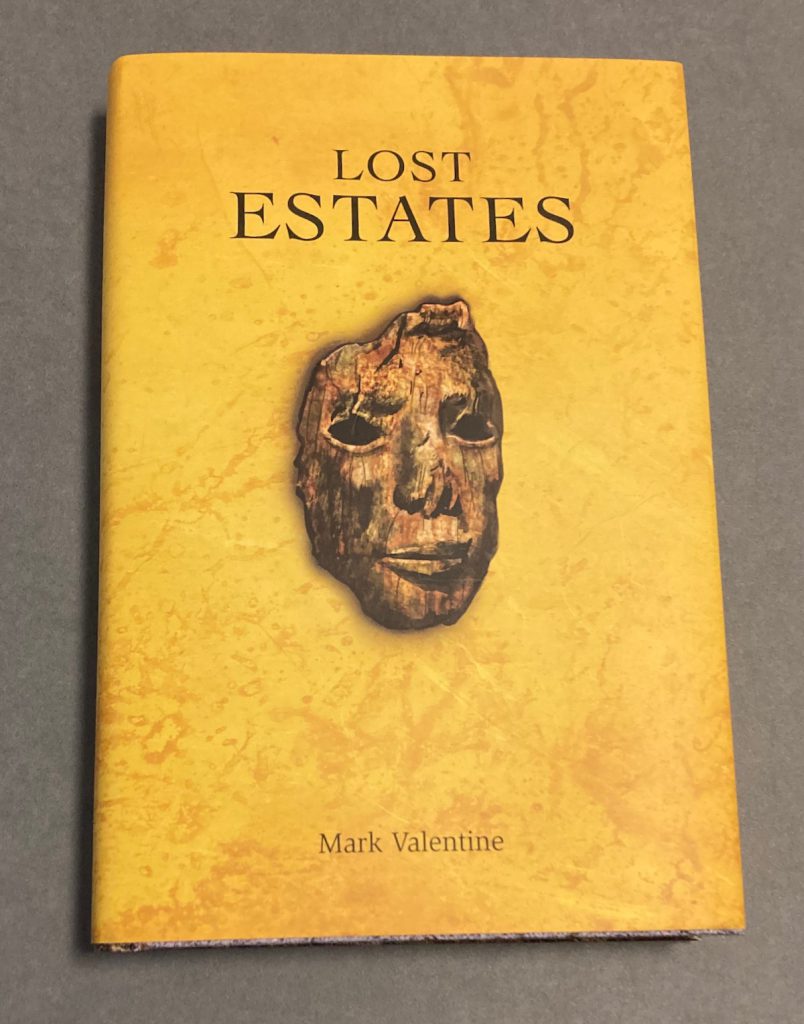

a big issue, with “An Incident in Monte Carlo”, a fragment or outtake from the forthcoming Wreckage by Peter Straub, new work by Elizabeth Hand, James Morrow, Timothy J. Jarvis, Mark Valentine, Reggie Oliver, and many others.

“Fern’s Room” by Liz Hand is pitch perfect, deftly moving from a gentle rom-com American anglophile country house idyll to a very dark endgame, with clues scattered all along the way.

“Plunged in the Years” by Jeffrey Ford, with a few steps off the path in the woods, gets right to the heart of the American ghost story : time and memory (and childhood).

— — —

recent reading

— Len Deighton. Faith [1994]. Grove Press, [2024].

— Margery Allingham. Sweet Danger [1933]. Penguin Books, [1963].

— Nathan Ballingrud. Crypt of the Moon Spider. Nightfire, [2024].

— Avram Davidson. The Adventures of Doctor Eszterhazy. Owlswick Press, 1990.

— — —

books wait for their readers

All antiquarian booksellers have a shelf of what Bill Reese called ‘intractables’ : things that sit on a shelf and seem unsaleable, or just beyond the grasp of one’s understanding, or, indeed, actively resist the efforts of the cataloguer with what M. R. James called the ‘malice of inanimate objects’. And then, suddenly, one finds a new perspective, or works with someone who has the key, and the door unlocks. I am fortunate to have experienced this a few times in my career. To watch this phenomenon in real time is one of the delights of the profession.

The question of whether or not books wait for their writers is trickier to answer. This is a question of a different order. I would say yes, on balance, but one feels the clock ticking, and the list of books not written is very long.

— — —

‘to escape the straitjacket that had been science fiction’ — Paul Kincaid

an excellent essay by a clear-eyed critic ringing the changes on Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions anthologies then and now :

http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/who-is-in-danger/

— — —

Eighteen Years of the Endless Bookshelf

Last week marked eighteen years of ‘simply messing around in books’ and reporting the pleasures on this website. It is still fun and so I will continue to note interesting books, curious passages, announcements, occasional snapshots, and digressions.

— — —

an Endless Bookshelf quiz

Who is the Widmerpool ?

— from your year(s) at school or university

— of your chosen field or profession

— observed recurringly elsewhere

/ wrong answers accepted

/ bonus points for naming your favorite book in ‘A Dance to the Music of Time’

— — —

4 January 2025

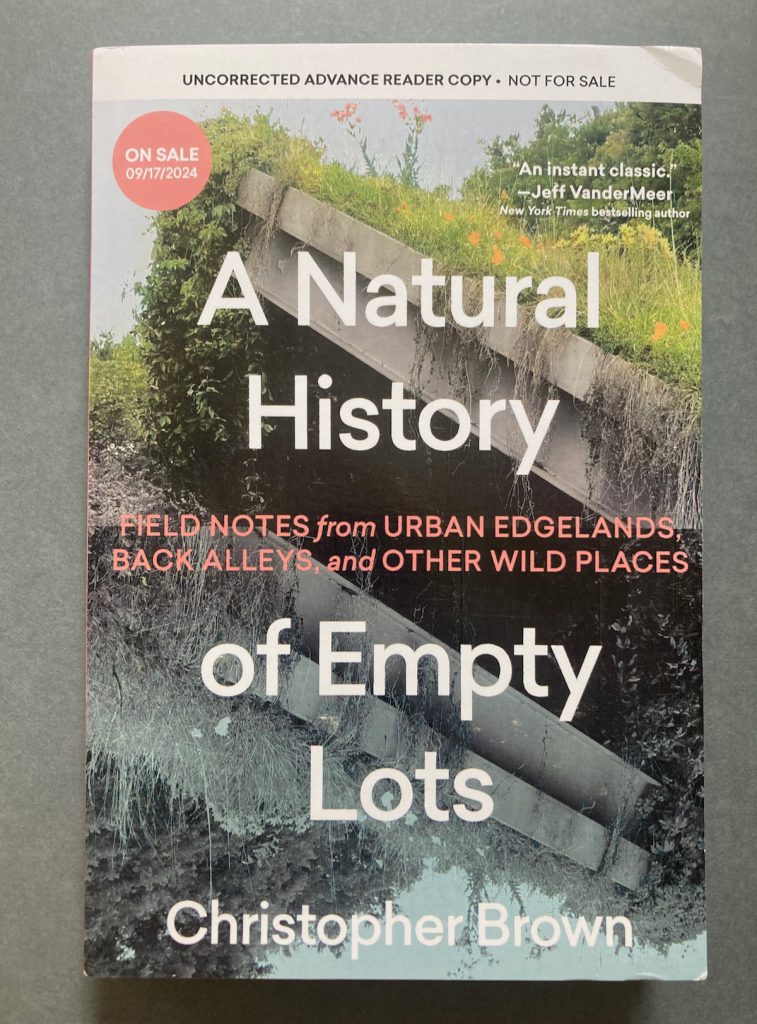

early in January, and it is already a good year in books, having just received two long-awaited titles in this week’s mailbag

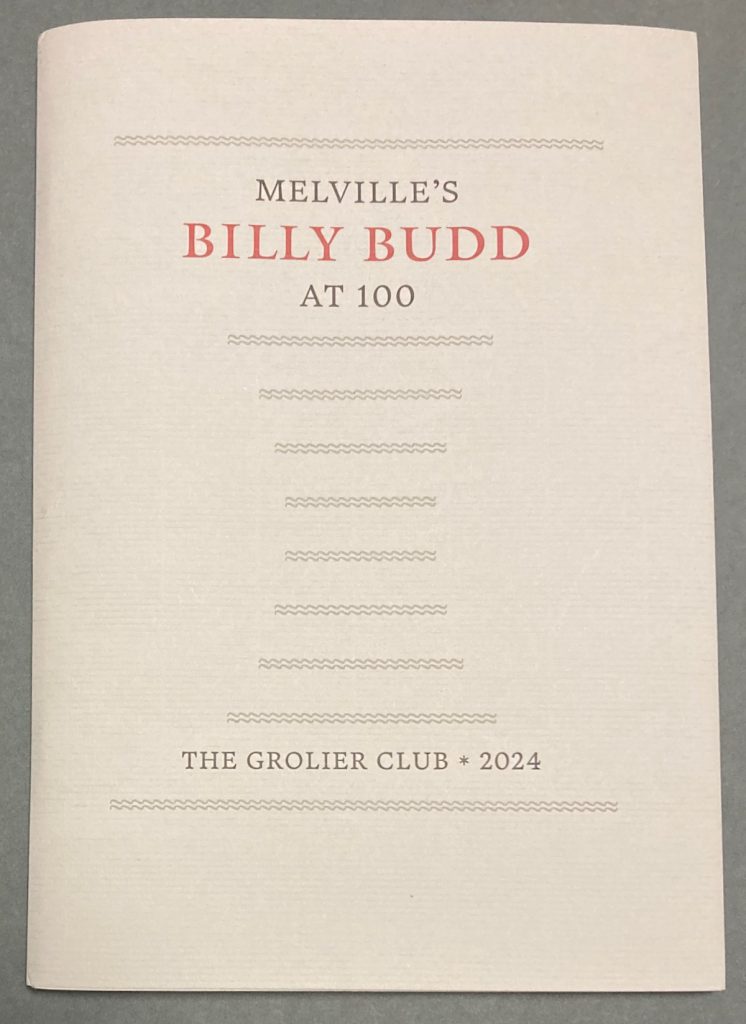

Billy Budd at 100 (continued)

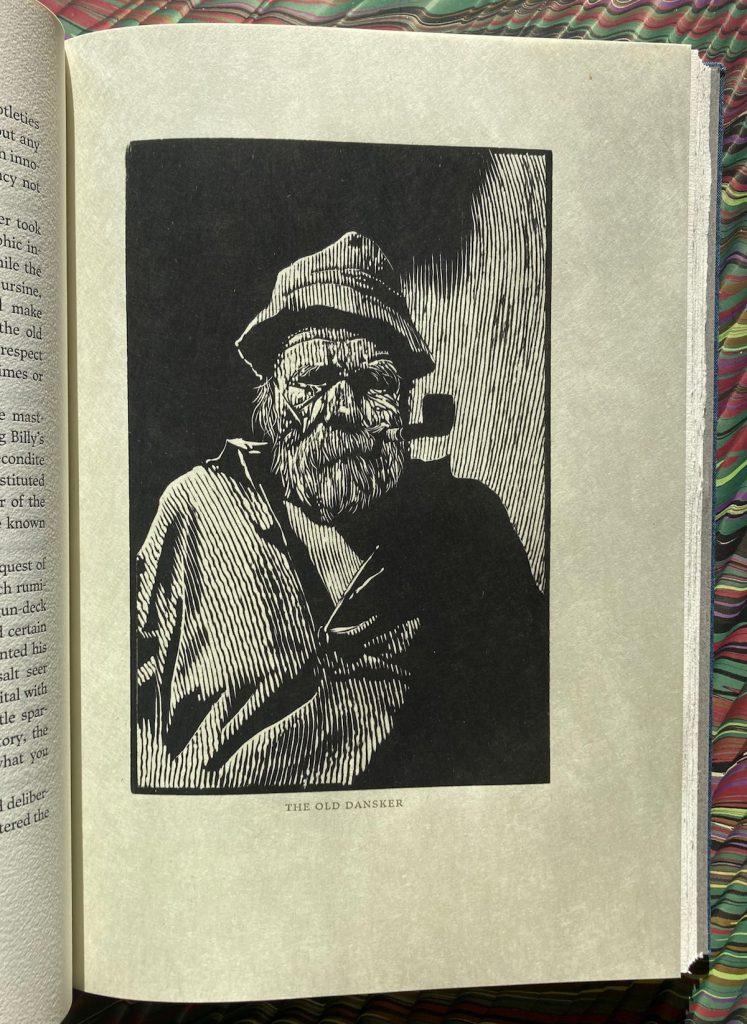

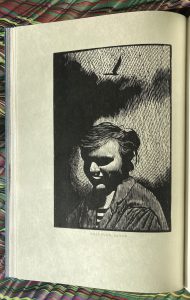

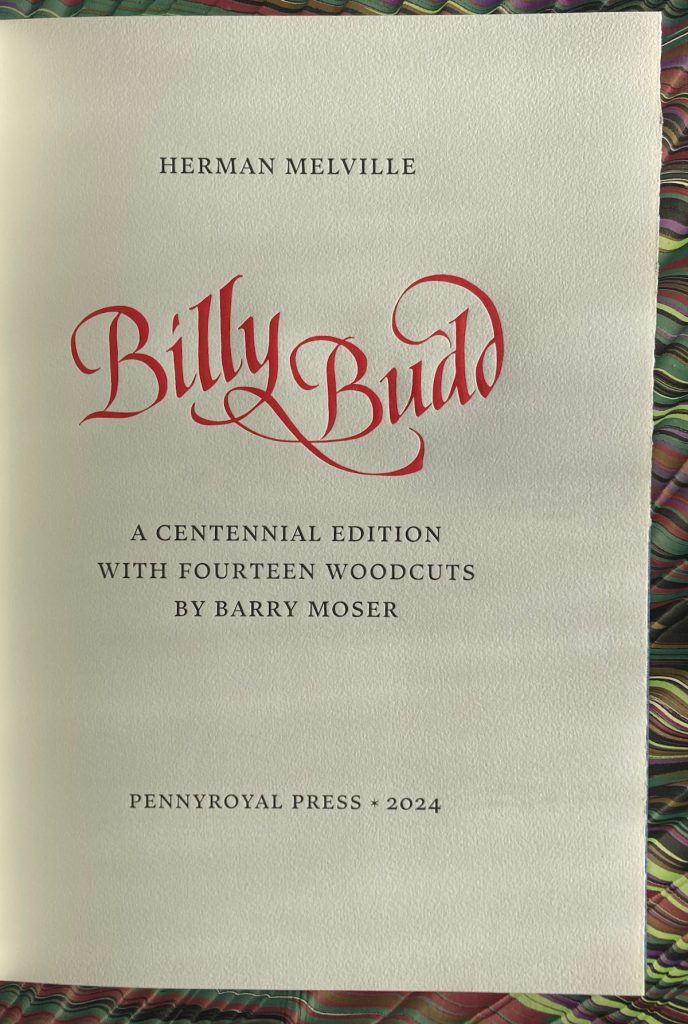

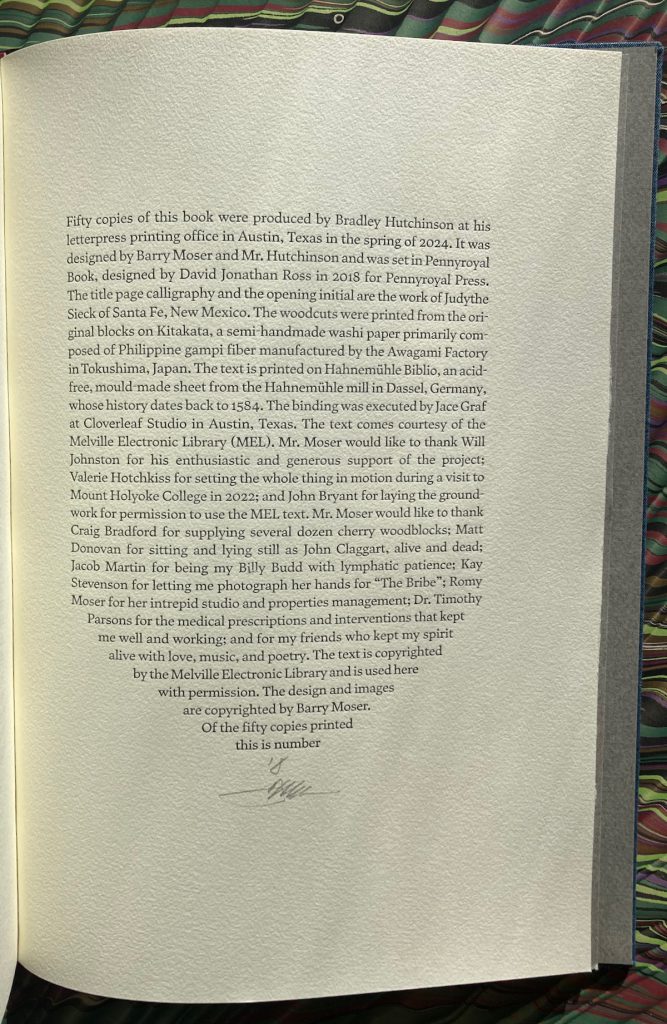

— Herman Melville. Billy Budd. A Centennial Edition with Fourteen Illustrations Cut in Wood by Barry Moser. Pennyroyal Press, 2024. Edition of 50 copies signed by the artist.

A spectacular new large format edition of Billy Budd Sailor (An Inside Narrative) — as the half-title names the book. The text of the novella is set from the Melville Electronic Library, with original woodcuts by American master Barry Moser.

— — —

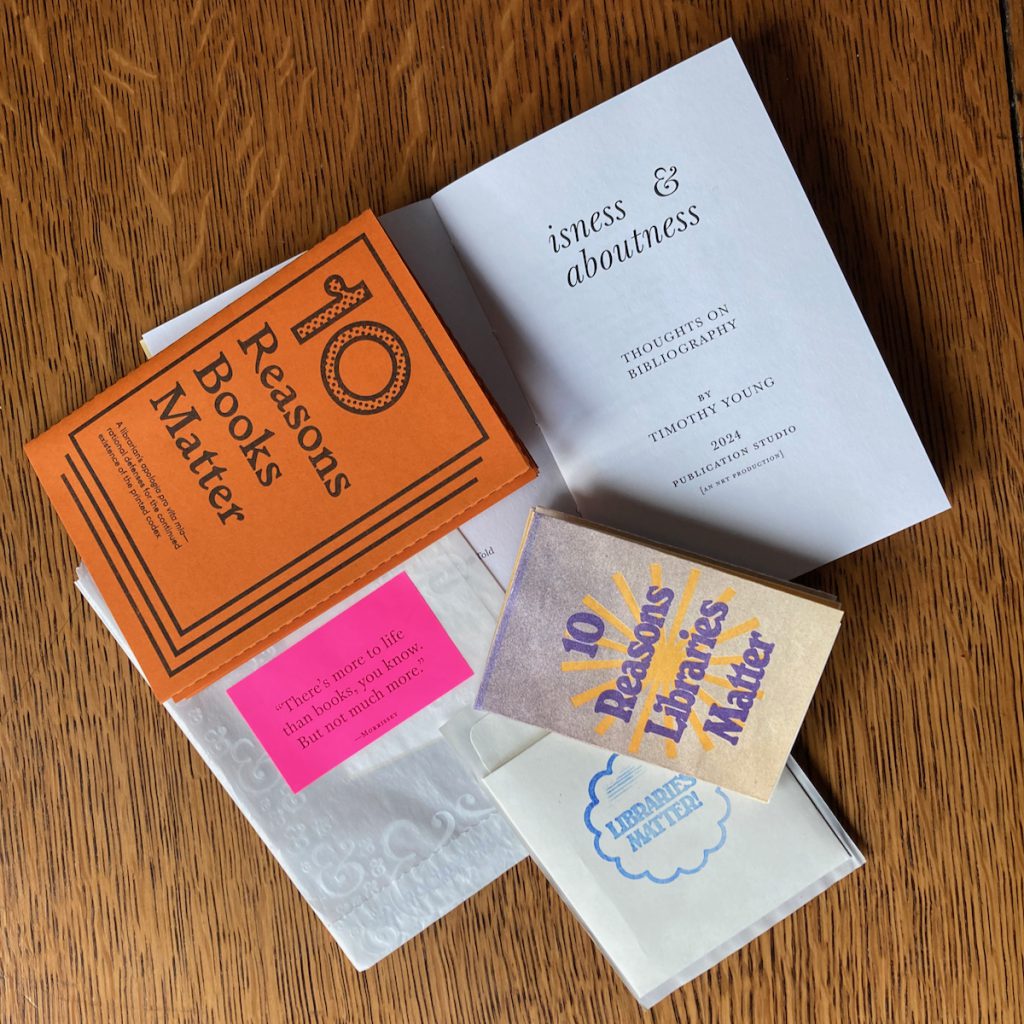

— Timothy Young. Isness & Aboutness. Thoughts on Bibliography. Publication Studio, 2024.

With two single sheet ’zines, printed rectos only :

— 10 Reasons Libraries Matter, 2021.

— 10 Reasons Books Matter, [2015].

Isness & Aboutness is a really great essay on thinking about books and thinking about the world (it is the text of Tim’s Sandars lecture at Cambridge University in November). He cites Donald McKenzie to good effect, on bibliography as

the only discipline which has consistently studied the composition, formal design, and transmission of texts by writers, printers, and publishers; their distribution through different communities by wholesalers, retailers, and teachers; their collection and classification by librarians; their meaning for, and — I must add — their creative regeneration by, readers [. . .] no part of that series of human and institutional interactions is alien to bibliography

His essay moves beyond McKenzie’s assertion to identify new modes of bibliography and to assert the primacy of bibliography as a means of uncovering what books are and what they do in the world. Highly recommended.

— — —

snow day, 11 January 2025

— — —

great blue heron flying low over the silvered mere

alighting on the ice beside a stand of reeds

in the distance, the pulaski skyway

/ from the train window this morning [16 January]

/ file under : extreme commute

— — —