— — —

— — —A singular interview with Brendan C. Byrne

— — —

— — —simply messing about in books

— — —

— — —recent reading : early june

— Tom LaFarge. The Crimson Bears. Part I. Sun & Moon Press, [1993].

——. A Hundred Doors. The Crimson Bears. Part II. Sun & Moon Press, [1994, i.e., 1995].

/ I have loved The Crimson Bears ever since I first encountered them, I read read them aloud to the offspring, and wrote about them, and about the early career of Tom La Farge (1947-2020) here : https://endlessbookshelf.net/bargeton.html

Am re-reading these in advance of the re-issue by Tough Poets Press. This is fabulous news !

— Paul McAuley. War of the Maps [2020]. VG [Gollancz], 2021.

/ what a writer ! McAuley makes it happen. Everything is otherwise but there are echoes & riffs of Beckett early on, and I see everywhere threads of Le Guin (The Dispossessed, in particular) ; and now, far out in the world ocean, a glimpse by the lucidor protagonist of world wanderers (an albatross by any other name) conjures up all the ripples of Coleridge ; and the deployment of Chekov’s dictum is deft and sudden. McAuley’s unexpected turns are shocking, deeply satisfying, the work of a magician who sets up his effects with precision and perfect timing.

— — —

this just in

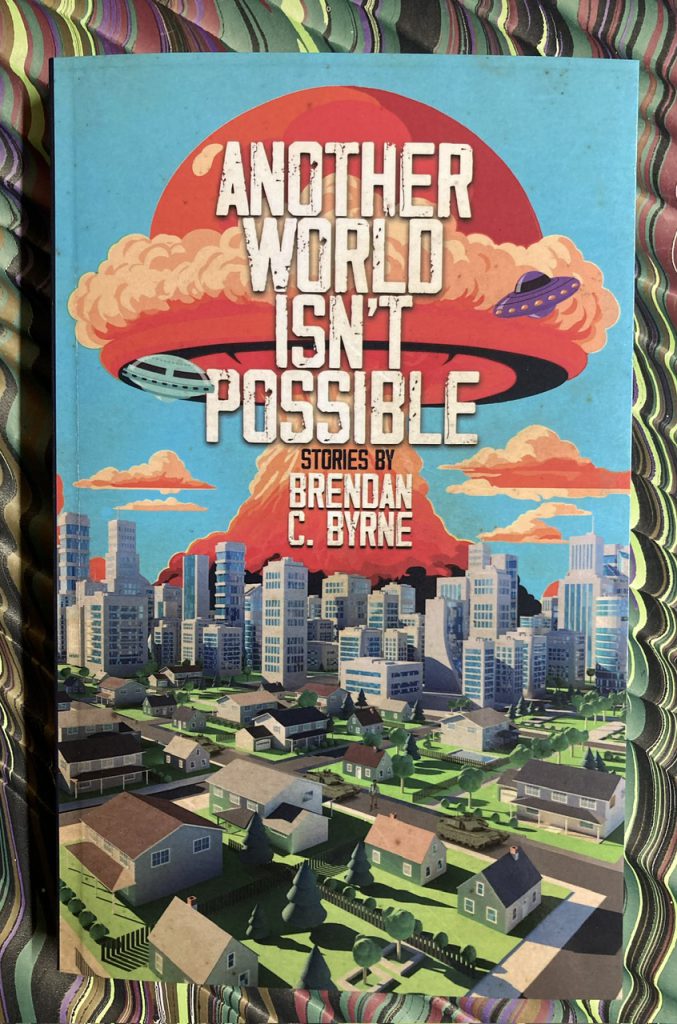

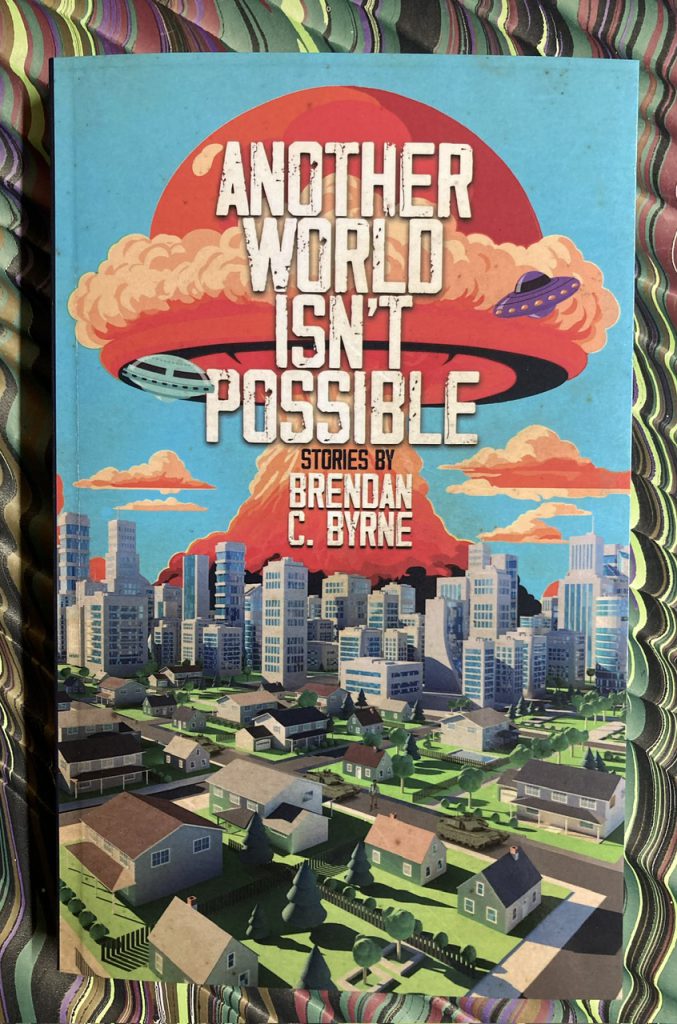

— Brendan C. Byrne. Another World Isn’t Possible. Stories. 226, [4], [6, ads], [3, blank], [1, imprint] pp. [Melbourne :] Wanton Sun, [2025 : POD, Chambersburg, Penna., 5 June]. Cover by Matthew Revert.

/ I know a few of these stories (even published one), but wow ! have I been looking forward to this collection. Stylish design !

/ from the blurbs : “Ruthlessly hip, transreal surreal. Worth your time.” — Rudy Rucker

— — —

various :

— Brian Eno and Bette Adriaanse. What Art Does. An Unfinished Theory [2024]. Faber, [2025].

/ serious, playful thinking about the what and why of art.

/ the Endless Bookshelf reminds readers of the Humument fragment by Tom Phillips, “the reader is the artist” :

https://temporary-culture.com/conversation43e/

— Colin Wilson. Jorge Luis Borges. Cover with portrait drawing by Hugo Manning. London : Village Press, 1974.

/ literary journalism by Colin Wilson, reductive in tone, and in the end more interested in himself than in the writings of Borges

— John Shen Yen Nee and S J Rozan. The Railway Conspiracy. Soho Crime, [2025].

— William S. Reese. The Best of the West. 250 Classic Works of Western Americana. William Reese Company, 2017.

/ succinct illustrated discussion of books (1555-1941) that chart the exploration and settlement of the American West.

— — —

— Mark Hanusz. Kretek. The Culture and Heritage of Indonesia’s Clove Cigarettes. [With a foreword by Pramoedya Ananta Toer]. Illustrated in color throughout. [xx], 203 pp. Equinox Publishing, 2000.

/ heard about this from a new acquaintance who grew up in Indonesia and described the sensory rush of memories arising, years later, from finding a discarded packet of clove cigarettes. Never smoked them myself but the olfactory memory is there. Bought two copies, one for a friend interested in the history of smoking and related phenomena.

— — —

— Heiress. Sargent’s American Portraits. 16 May – 5 October 2025 [Cover title]. [Foreword by Richard Ormond]. English Heritage | Kenwood, 2024.

/ Catalogue of an exhibition of 18 portraits by John Singer Sargent, with summery biographies of the American heiresses who married into the British inner circles and aristocracy. An excellent, compact show. Ormond is author of the Sargent catalogue raisonné.

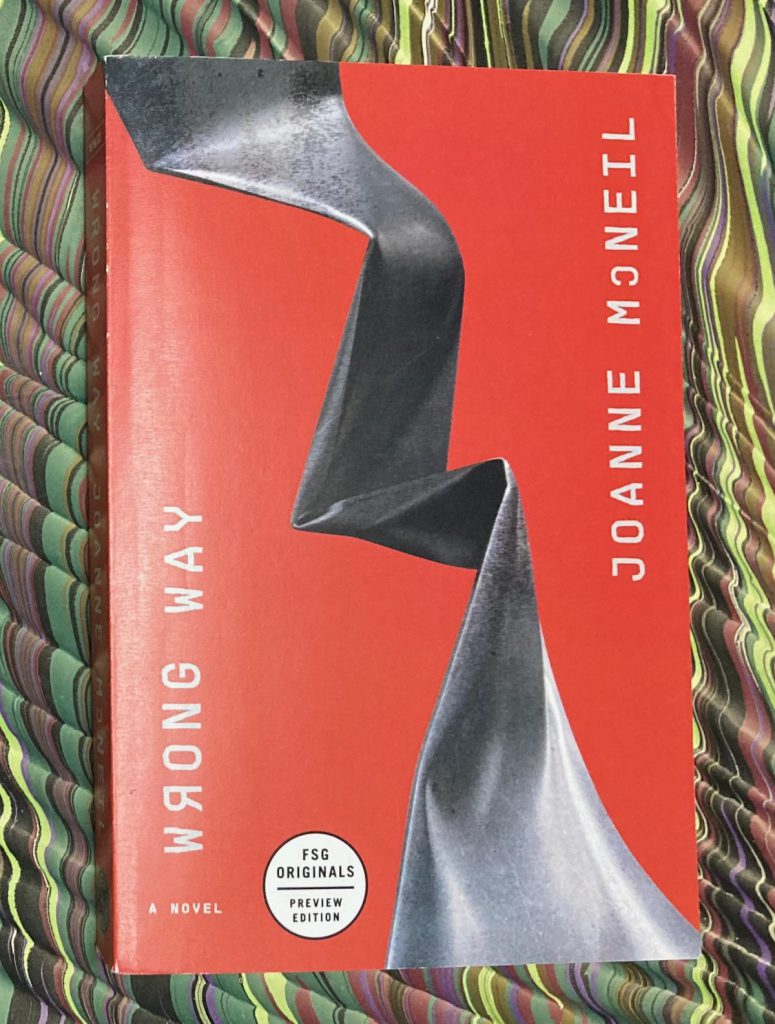

— Joanne McNeil. Wrong Way. MCD x FSG Originals, [2023].

i see things from

the under side

Don Marquis, the lives and times of archy and mehitabel

Drop everything and find a copy of Wrong Way.

This remarkable book is many things : a deep history of America through the lens of marginal employment, a social history of isolation, and an economic palimpsest of the architecture of New England mill towns. Wrong Way is the first novel by Joanne McNeil, who has a fine ear for American usages and a sneaky sense of humor evident from the first pages; her entangling memoir of technological change, Lurking. How a Person Became a User (2020) is well worth looking for. Wrong Way is a science fiction novel of the near new future, charting the life and times of Teresa Kelly, a Massachusetts woman in her late forties who swims laps the way others might jog or cycle or meditate, and who aces a virtual hand eye coordination test. “There is nothing to win,” says the recruiter, except that is never really true.

We follow Teresa in a close third-person narration that attends to small sensory details in the present and is resilient enough to sustain digressions into a litany of the jobs she has held over the years. “This could be a good job . . . ” is the voice of a pragmatic optimist and, it becomes clear, actually a pretty high bar.

The opening chapter is superb in its evocation of Teresa’s present circumstances and where she came from. Her first job as a teenager was at the jewelry counter in the showroom for an omnipresent catalogue company. “It was a good job, but those stores don’t exist now. Those jobs don’t.”

Say “Cedars” softly, without stressing the medial dental consonant.

The cognitive estrangements creep in swiftly and subtly as the shuttle bus proceeds from Boston South Station to a long-abandoned airport now repurposed as Render Falls, regional hub of the “worker first” internet company AllOver, “more than a service and experience platform”: it functions as search engine, ticketing conciergerie, payment processing, digital currency, and more. Teresa has been hired as a contract worker in the driverless car division, CR, a “transportation alternative” for top tier AllOver users. The AllOver executives — Falconer Guidry, CEO and self-made man, and Vermont Qualline, SVP of automotive engineering and daughter of a nineties country singer — have stepped from the pages of the business section of tomorrow’s newspapers, and the AllOver corporate rhetoric, ecological self-righteousness, and aspirations to a “Holistic Apex” are pitch perfect. Teresa is mature enough, and jaded enough, to be a skeptical witness, and some of the other trainee “seers” who answered the Drivers Wanted ad voice their doubts about the AllOver mission. “What kind of bottom-up change begins with people who spend fifty gs or so on an app every year?”

‘like a cockroach hiding in the kitchen walls’

The billboard in Brixboro that used to say “We Will Buy Ugly Houses” has been replaced by a picture of Plum Sasha lounging in a CR. Her teeth and blue eyes are clear and perfect. She looks carefree and young. There’s a retro eighties feel to the bubbly blue letters that read, “Luxury. Privacy. Spotless. Priceless. The CR has arrived. See it.”

Plum Sasha is an “icy-looking” teenage influencer and the advertising campaign for AllOver’s “CR driverless experience” is omnipresent. It is good advertising and pretty tough going those on the delivery side of the product. Teresa soon discovers her work as a “seer” at AllOver is not what she expected, and that things are not what they seem. On page 89, Teresa sees clearly: “It seems obvious, from the moment she sees it, but it never occurred to her earlier. Every trainee in the hangar has dark hair. There’s something else they all have in common: slim, compact bodies. It is a room of ectomorphs, each one of them about five and a half feet tall, give or take a couple of inches. Long limbs and short torsos. Bodies small enough to hide.”

At pages 110-11, things as they are become even clearer, in a “moment of weightless surrender [. . .] She is uncomfortable, still, and clings to her discomfort — once driving the CR feels natural to her is the moment she will lose control.” Coupled with the downward spiral of Teresa’s past work experiences — “The longer she worked at the museum, the more it felt like training in reverse” — this might suggest a pretty bleak book, but McNeil’s nimble prose and her eye for beauty in the mundane offer a different arc. The epigraph to this review, the refrain from “ballade of the under side” by Don Marquis, articulates my sense, from the earliest pages, that this is a novel from the economic underside of the American tech miracle. And so it was a small pleasure to see the simile “like a cockroach hiding in the kitchen walls” at page 119, part way into into the narrative drive. For drive it is: Wrong Way threads and weaves through the greater Boston area with a sureness of inborn knowledge — I have visited many times and still have no clues as to how Cambridge and Boston and the Charles River are braided together.

‘Route 128 when it’s dark outside’

We read and write on analog paper, and we read and write on electronic paper. We live in a world where the analog and the digital reciprocally permeate each other; we are hybrids, and so are our media.

Lothar Müller, Weiße Magie / White Magic, The Age of Paper (translated by Jessica Spengler)

Science fiction demands that metaphor be taken literally. Wrong Way is a science fiction novel about the hybrid nature of work in the twenty-first century. Teresa puts herself — contorts herself — into her job in a way that employers take to the bank. Capitalist systems are designed for economic returns with little heed for the human costs. “When things are good with work, all it means is, things will get worse.” The soundtrack to Wrong Way might well include “Roadrunner”, Jonathan Richman’s paean to the highway late at night, Route 128 when it’s dark outside, just before a tech boom that forms part of the geologic past of Wrong Way. The brief moments of camaraderie with fellow seers or with truck drivers are nicely done yet serve only to highlight a chronicle of isolation. I don’t want to leave the wrong impression: Wrong Way is a novel that addresses serious topics with flashes of wit and wild imagination. McNeil takes the reader to strange places. And just what happens in the last two chapters will be a matter of personal interpretation. I can’t wait to discuss it with other readers.

Drop everything and find a copy of Wrong Way. It’s an engaging and provocative work, the best book I’ve read this year.

The Endless Bookshelf book of the year 2023.

‘merging, not with the car, but with the road’

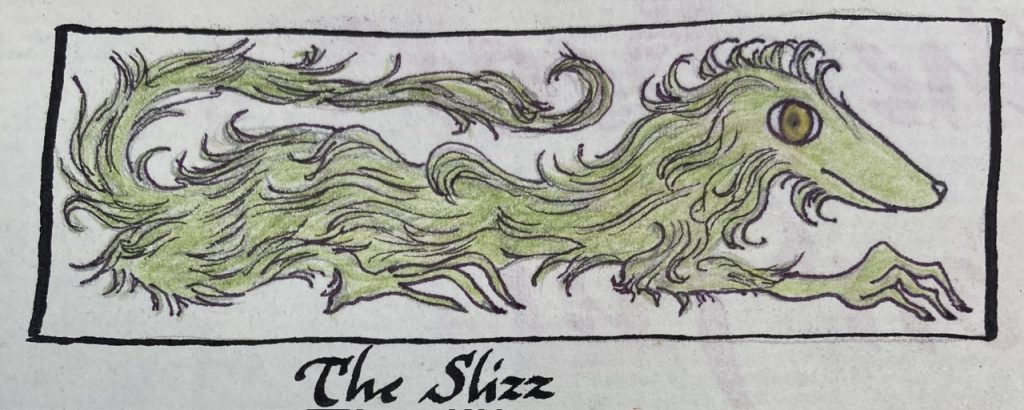

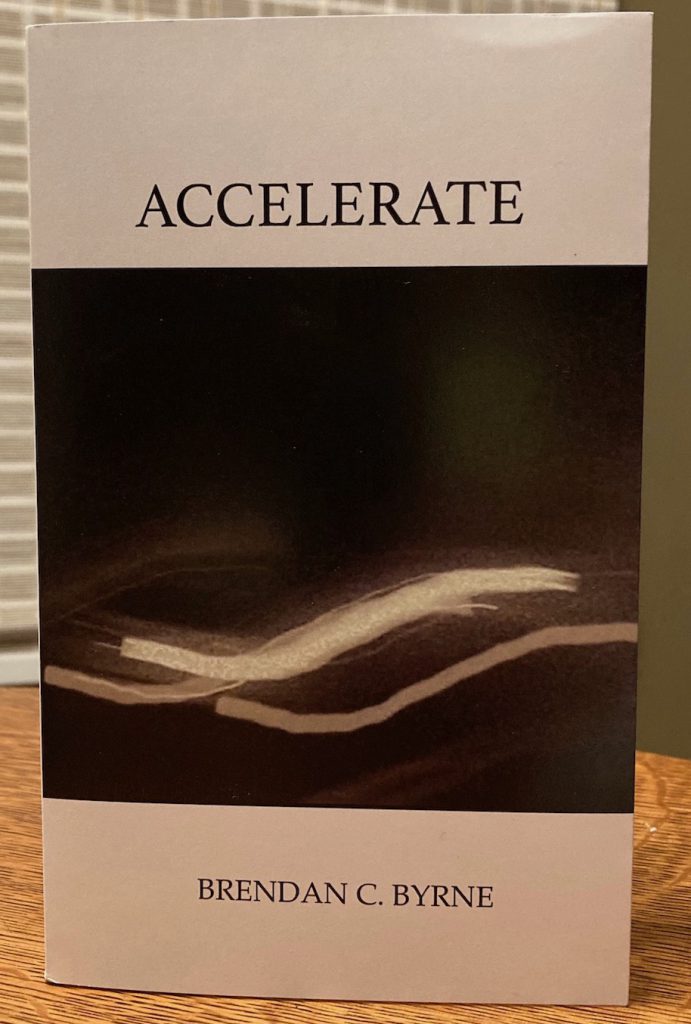

— Brendan C. Byrne. Accelerate. 96 pp. Small 8vo, [Moonachie, New Jersey], 2022 [i.e., 3 November 2021]. Pictorial wrappers, dust jacket with french flaps. From a small edition printed for the author just before the publication of the e-booke by Neotext. The title page verso reads Copyright 2020.

This is a remarkable book. In a future Los Angeles, couriers caged with their autonomous vehicles pound nutritional “sluice” and make deliveries at 198 m.p.h. Joam has refused to let the hardware make all his driving decisions yet lives almost integrated within his armored “beater”. He receives a commission to deliver a packet to New York within 72 hours. The narrative is all attitude and the lingo is a brilliant street jargon, an immersive account of Joam hurtling across the landscape of American political collapse, seeing off jealous rivals. Some of Byrne’s earlier work, such as “a Stone and a Cloud”, seems to chart the erosion of humanity in the technological future. Accelerate is a gonzo cross-country road-trip — west to east — which tells a moving story of personal loss as, paradoxically, the machine becomes human. The best book of the year 2021.