Dear friends and readers,

here is the third update of the Endless Bookshelf during the pandemic year 2020, when time has seemed at once to dilate and to compress. It has sometimes been difficult for me to write new work in a sustained manner. Blurred lines, or the deadline of no deadline. Others may enjoy virtual conferences but these have not attracted me or prompted me to finish a story the way that a scheduled reading slot at Readercon always used to. It has, however, been a year of many good books old and new.

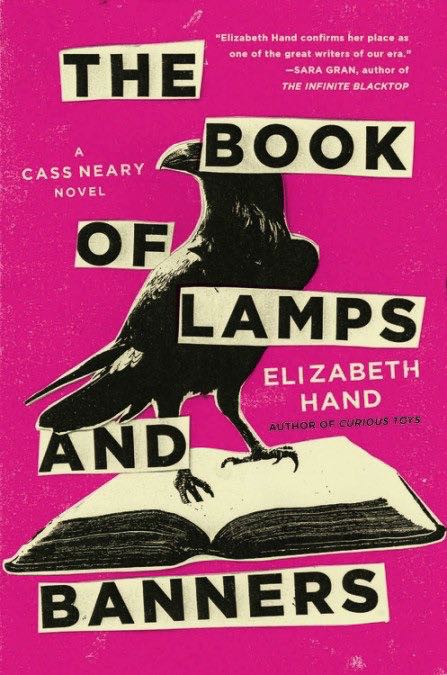

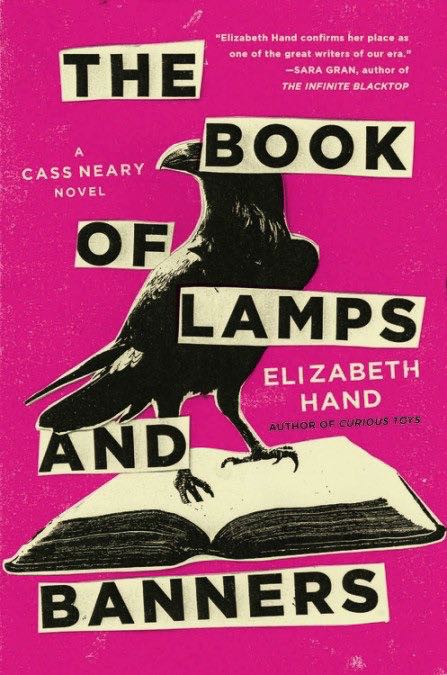

— Elizabeth Hand. The Book of Lamps and Banners. A Novel. Mulholland Books, [2020]. I am the dedicatee of this book, and perhaps more. It is a signal honor to be part of the latest in Liz Hand’s chronicle of the adventures of Cass Neary. I had read some early versions of the novel in typescript, but when I got my copy on publication day in September, I was compelled afresh. As Cass says, ‘I couldn’t rest.’ I read it straight through into the early hours of the morning. A pretty intense philosophical object is at the heart of the novel (see below under recent reading). Disqualified from reviewing the book and constrained by my own conscience from naming it the best book of the year (or declaring a tie with The Private Life of Books), I am free to urge you all to read the novel. I am pleased to present

A Singular Interview* with Elizabeth Hand

Henry Wessells The London of the Cass Neary novels always seems rooted in lived experience. How did you come to the house of Harold the bookseller?

Elizabeth Hand You’re absolutely correct that nearly everything in the Cass novels is drawn from my own experience (with a few exceptions — murders, fatal overdoses, ritual sacrifices, etc.). Harold Vertigan’s rare bookshop-cum-home is no exception, though as you well know, Harold actually lives and works in the NYC metro area.

For the book, however, I transplanted him to North London, to a particular minuscule enclave, Vale of Health, a hamlet in Hampstead. I came across it some years ago while wandering on the Heath, one of my very favorite things to do in London. Vale of Health is a tiny village hidden toward the upper part of the Heath, with a very few very narrow winding roads and mostly small old houses, some linked by cobblestoned alleys lit by old-fashioned lamps — they resemble some lost corner of Narnia.

The whole place appears utterly charming and otherworldly (not excepting the parking area filled with caravans, trailers, and retired food and ice cream trucks). So of course I knew I would have to use this lovely setting as the scene of an awful murder: the fictional Harold, with his wide-eyed delight at all things, his mild eccentricities (bare feet, seersucker in winter), impeccable taste (fine champagne), and deep knowledge of the book trade, could only live (and die) in a place like the Vale of Health. His real -life counterpart, on the other hand, will be discovering rare books and edible mushrooms for decades to come on this side of the great grey water.

—

* I thank my friend Michael Swanwick for this useful conceit.

— — — —

— Ng Yi-Sheng. Black Waters, Pink Sands. Math Paper Press, [2020]. This newest book from the author of Lion City presents two recent performances written by Ng Yi-Sheng: Ayer Hitam: a Black History of Singapore, and Desert Blooms: the Dawn of Queer Singapore Theatre. Ayer Hitam is a remarkable history of the world through an examination of the history of Black people in Singapore.

— — — —

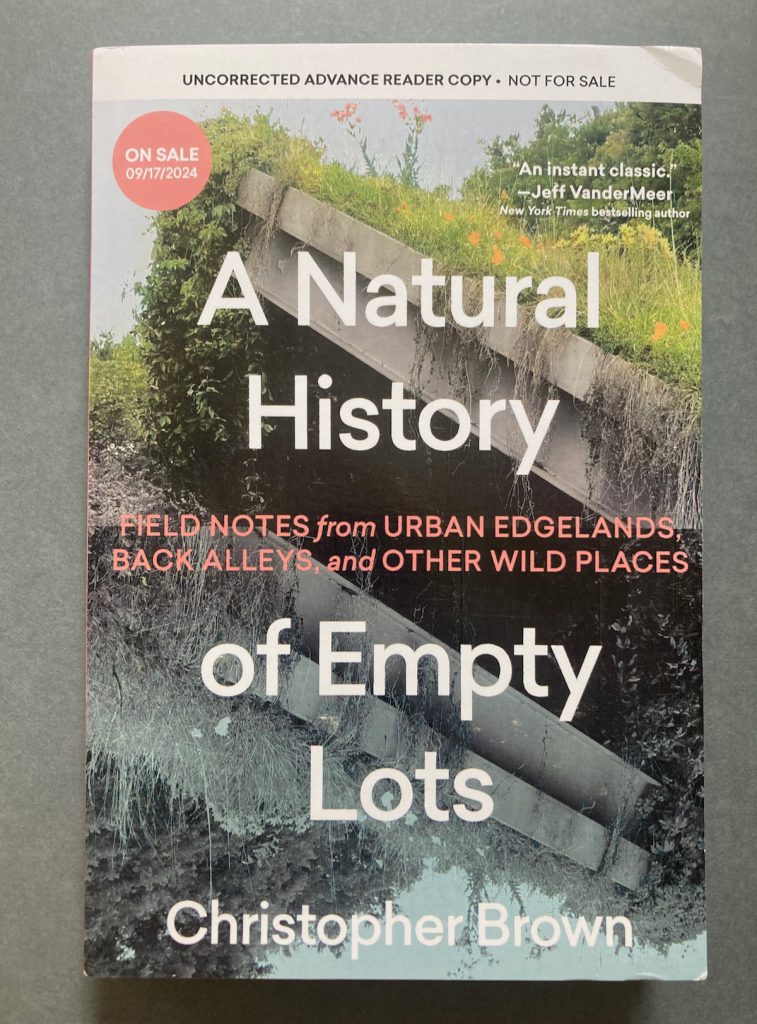

The weekly Field Notes of Chris Brown, a newsletter of ‘ecological fact as applied science fiction’: https://edgelands.substack.com

— — — —

The Avram Davidson Universe

During this year, Seth Davis has brought many stories by Avram Davidson into audio book format, and initiated a monthly podcast The Avram Davidson Universe. I was happy to be a guest: it was a fun conversation with Seth Davis and a chance to consider “O Brave Old World!”, one of the stories from The Other Nineteenth Century. https://www.buzzsprout.com/1310005/6138964-the-avram-davidson-universe-henry-wessells-o-brave-old-world

Other guests have included Ethan Davidson, Eileen Gunn, and Michael Swanwick, who named Avram Davidson as “the best American short fiction writer of the twentieth century’.

— — — —

The release of The Booksellers documentary to a worldwide audience. https://booksellersdocumentary.com

# # #

Tom La Farge

Tom La Farge (1947-2020) died on 22 October. Tom was author of The Crimson Bears (2 vols., 1993-95), a modern classic worthy of a wider audience. Harvard class of 1969 (and former president of the Harvard Lampoon), with a doctorate from Princeton, he was the most literary man I have ever known. Quietly and without heeding fashion or compromising his vision, he wrote his books. He taught a generation of students in the English department at Horace Mann School. I knew Tom since 1993, and wrote about the early phase of his literary career in an essay for the New York Review of Science Fiction, now available here:

https://endlessbookshelf.net/bargeton.html.

Tom’s interest in writing with constraints, approached ‘dialogically and not ideologically’, led him to form the Writhing Society, some fruits of which can be found on its blog, http://writhingsociety.blogspot.com. He had recently completed The Enchantments, a series of three novels published 2015-18. Tom is survived by Wendy Walker and his son Paul La Farge.

— — — —

In Memoriam ‘Dirleddy’: Jan Morris (1926-2020)

My review of the remarkable fantasy of historiography and ultimate travel book, Hav (2006), originally published in the New York Review of Science Fiction for April 2007:

https://endlessbookshelf.net/hav.html

# # #

Back to Basics

current reading:

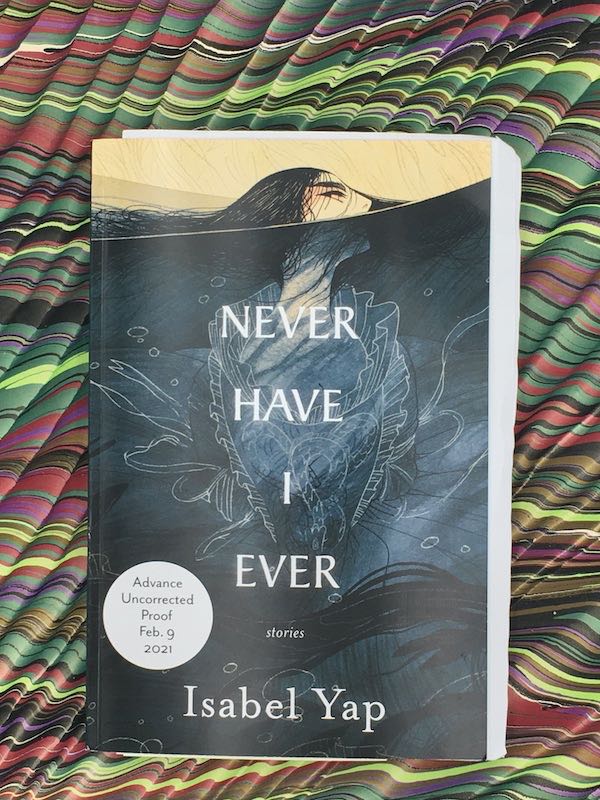

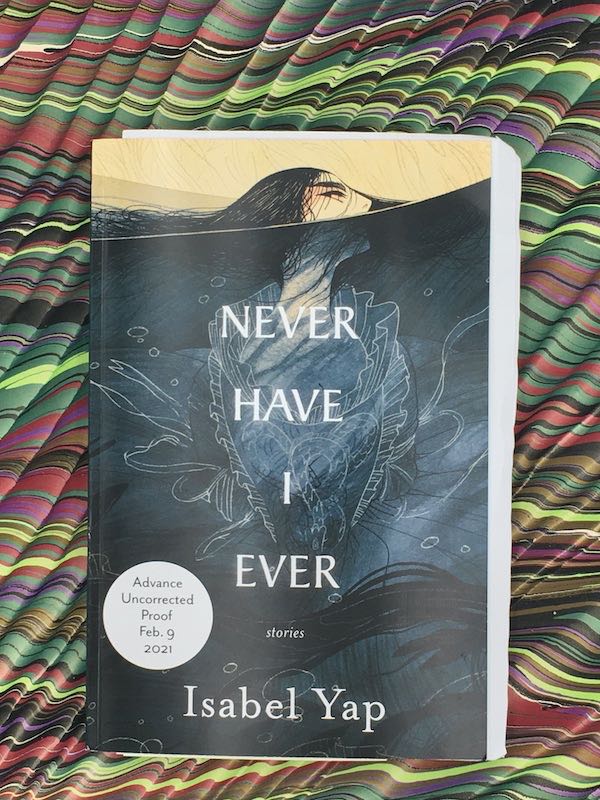

— Isabel Yap. Never Have I Ever. Stories. Small Beer Press, [forthcoming, February 2021]. Fantastical stories, published 2012-2018, by Manila-born author Isabel Yap, with three stories original to this collection. This arrived in today’s mail, and I am eager to read it!

— — — —

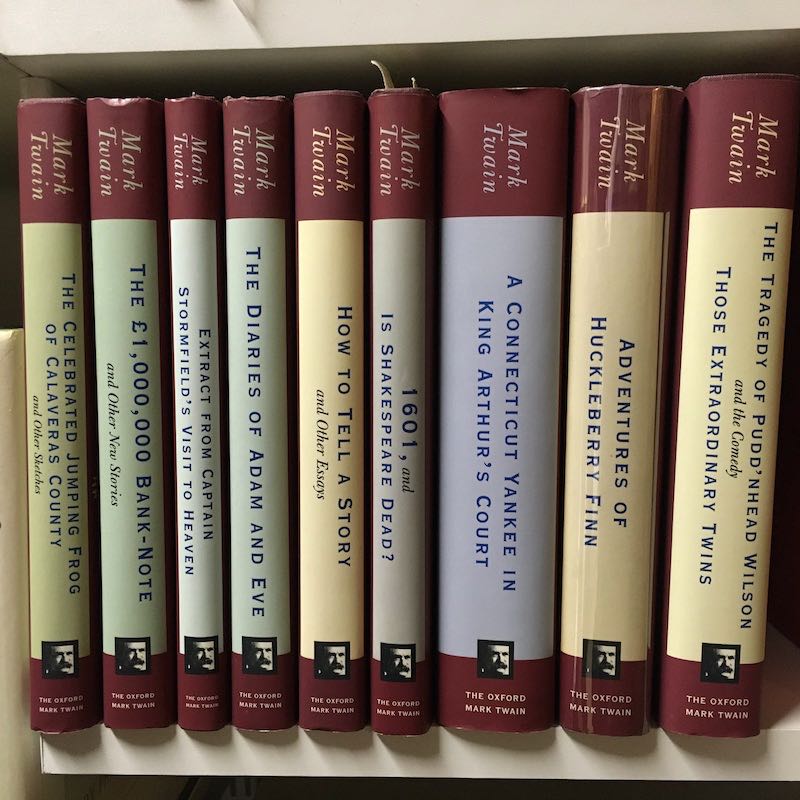

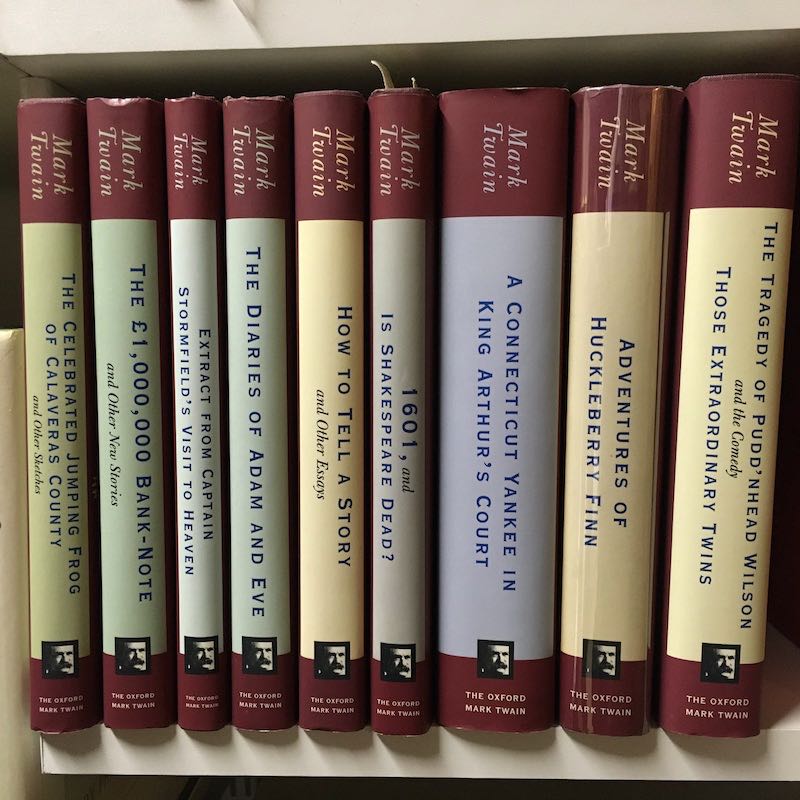

— Samuel L. Clemens. The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and the Comedy Those Extraordinary Twins by Mark Twain. Introduction by Sherley Anne Williams. Afterword by David Lionel Smith. Oxford University Press, 1996.

— — — —

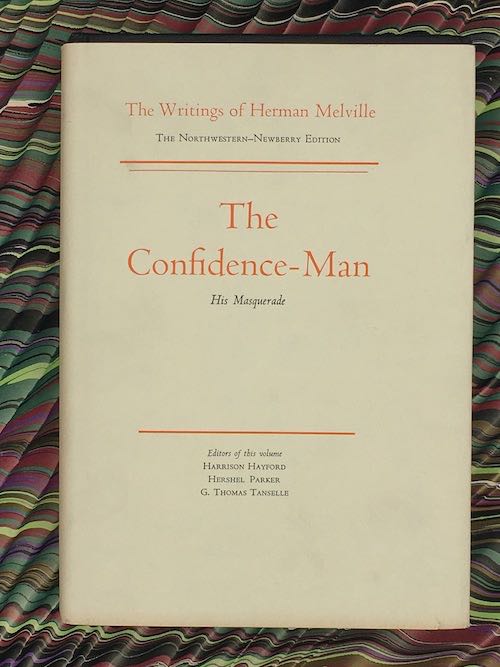

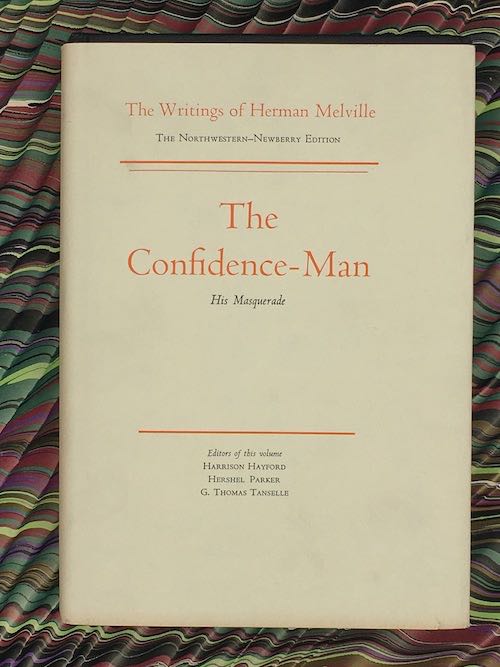

— Herman Melville. The Confidence Man His Masquerade [1857]. Northwestern University Press and the Newberry Library, 1984. Edited by Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, G. Thomas Tanselle. Northwestern Newberry Edition, volume ten. ‘As among Chaucer’s Canterbury pilgrims’, all along the river shore and on the planks of the Mississippi steamboat Fidèle, a work that cries out for performance. To read it is rewarding work.

— — — —

re-reading:

I am re-reading Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) in small bites, in the Penguin Classics edition (I have read it in first edition and in the 1892 Bentley edition); and over the past months have read several of the Travis McGee novels of John D. McDonald. I have been reading or re-reading at Samuel L. Clemens in the Oxford Mark Twain, a hybrid uniform edition: photofacsimile texts in standardized format with great new essays (Ursula K. Le Guin’s essay for The Diaries of Adam and Eve is outstanding; and Toni Morrison on Huck Finn).

— — — —

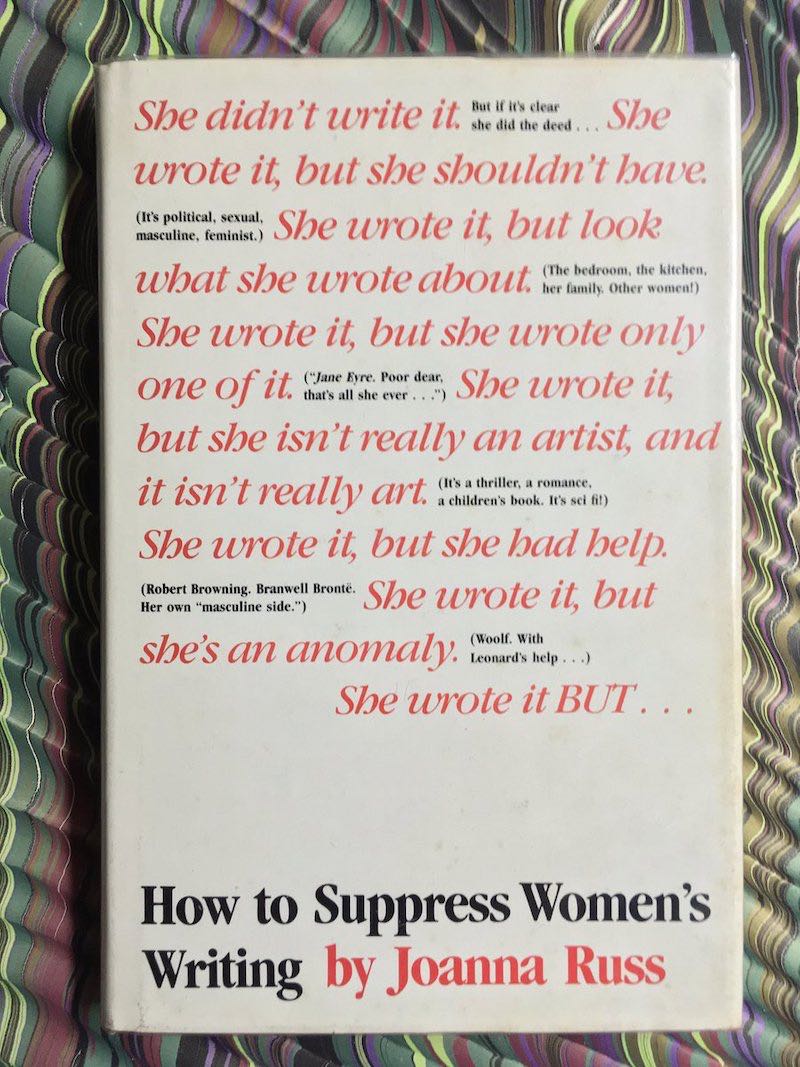

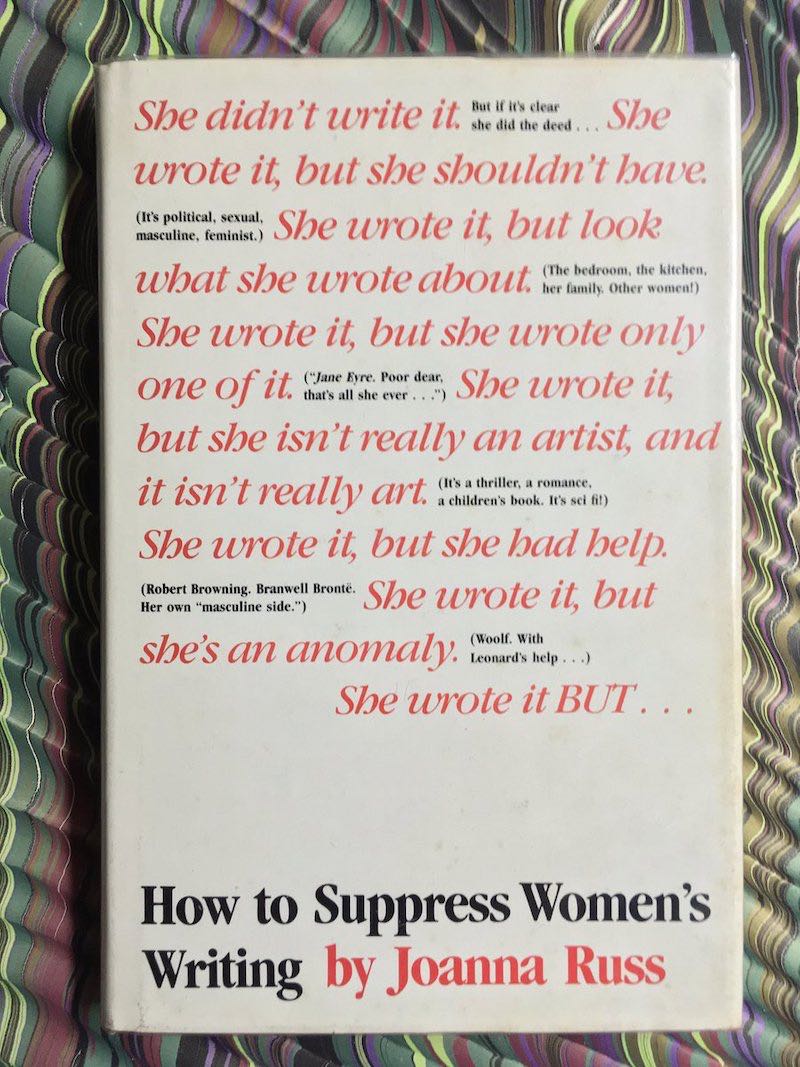

— Joanna Russ. How to Suppress Women’s Writing. University of Texas Press, [1983]. Always a delight and a provocation to read: ‘growth occurs only at the edges of something’. See also below, in the Commonplace book.

— Robert Louis Stevenson. Treasure Island. Illustrated by N. C. Wyeth. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925. A favorite book: foxed, shaken, the same copy I first read at age eleven.

recent reading:

— Tom Mole. The Secret Life of Books. Why They Mean More than Words. Elliott & Thompson, [2019]. This was fun. Clearly the author and I share some interests and predilections beyond the chance similarity of titles.

— Michael Swanwick. Rainbow Clause. Dragonstairs, 2020. Eight short short stories in his ongoing investigation of the taxonomy of American myth.

— [Donald E. Westlake] Richard Stark. Dirty Money [2008]. A Parker Novel. With a New Foreword by Laura Lippman. University of Chicago Press, [2017].

— — Deadly Edge. Random House, [1971].

— — Slayground. Random House, [1971].

— — Plunder Squad. Random House, [1972].

— P. D. James. A Taste for Death. Knopf, [1986].

— — The Skull beneath the Skin. Scribner’s, [1982].

— — Devices and Desires. Knopf, [1990].

— Feux Follets. Revue de création littéraire. Départment des Langues Modernes à UL Lafayette, [2020]. L’imaginaire louisianais in a nice rich anthology.

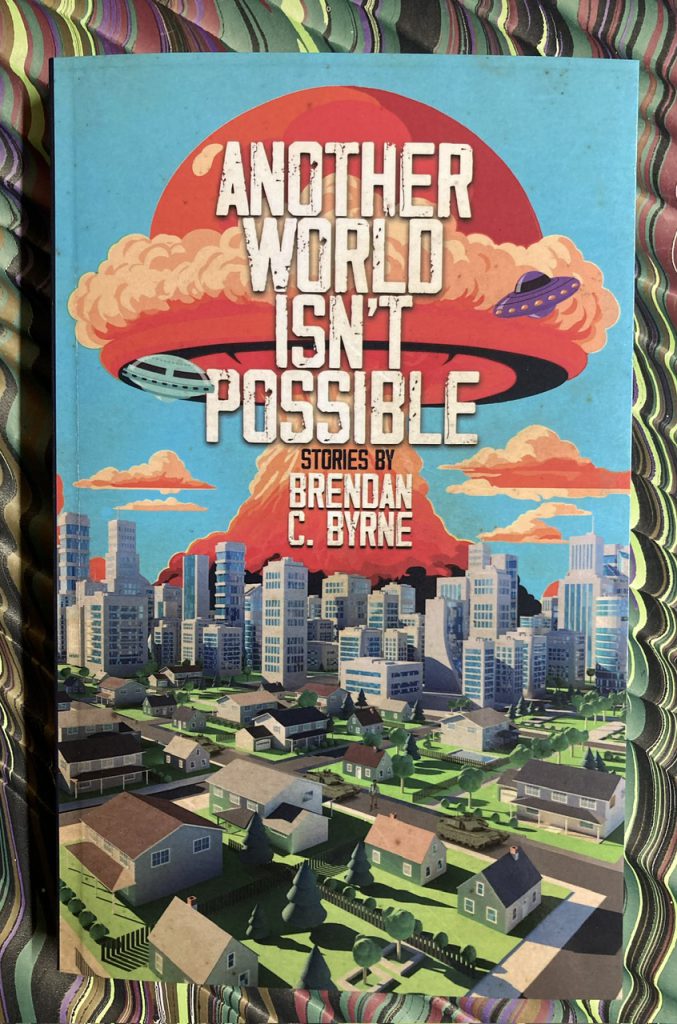

— Big Echo Interviews 2017-2020. Edited by Robert G. Penner. Big Echo, [POD: 6 November 2020].

— Lester Del Rey. The World of Science Fiction 1926-1976. The History of a Subculture. Garland, [1980].

— David Rothkopf. Traitor. A History of Betrayal from Benedict Arnold to Donald Trump. Thomas Dunne Books, [2020].

— Philip K. Dick. The Slave Race. With a Preface by Adam Newell and a frontispiece by Sharon Newell. Sangrail Press, 2020. Edition of 250 numbered copies. First 25 copies issued with an original blockprint initialled & numbered by the artist. A nice production.

— Michael J. DeLuca. Night Roll. Hamilton, Ontario: Stelliform Press, [2020]. A very good supernatural story of a new Detroit.

— Megan Rosenbloom. Dark Archives. A Librarian’s Investigations into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, [2020]. This is an advanced philosophical subject. The prose does not rise to the level of the topic. Far more interesting and informative is Jennifer Kerner’s interesting study, Anthropodermic Bibliopegy, (2019). See also the archives for November & December 2009.

— Mark Valentine. The Blue Coronation Bench. Photography by Julian Hyde. Voices in a Lane, 2020. Edition of 40. The hidden mystery of the everyday.

— Michael Swanwick. Blue as the Moon. Dragonstairs, 31 October 2020. Stories for Hallowe’en. ‘White as a Sheet’ is brilliant: swift and utterly devastating in the spiral of its change in tone.

— John Howard and Mark Valentine. Powers and Presences. Dust-Jacket & Title Page Art by Paul Lowe. [Neuilly-le-Vendin]: Sarob Press, 2020. Three new novellas and two short essays in appreciation of Inkling novelist Charles Williams (1886-1945).

— Strange Tales. Tartarus Press at 30. Edited by Rosalie Parker. Tartarus, [2020]. New stories from Reggie Oliver, Rebecca Lloyd, Mark Valentine, D. P. Watt, N. A. Sulway, and others.

— Mike Ashley. Starlight Man. The Extraordinary Life of Algernon Blackwood. Constable, [2001].

— Mike Ashley. Algernon Blackwood A Bio-Bibliography. Greenwood Press, 1987.

— M. John Harrison. Light. Bantam Books, [2004].

— — — —

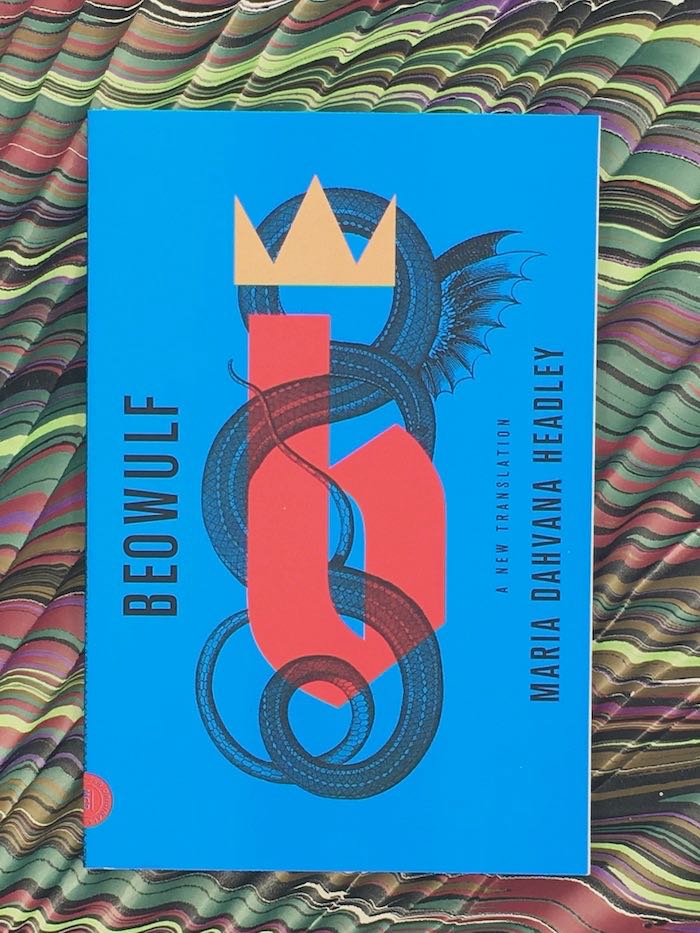

— Maria Dahvana Headley. Beowulf. A New Translation. MCD x FSG Originals, [2020]. Making it new: ‘stories that haven’t yet been reckoned with’ (from her introduction, dated on a distant day, 3 March 2020)

# # #

Commonplace book

‘To begin at the beginning: The United States has always been a corrupt society.’ — Gore Vidal

— — — —

‘Could it be that all these authors were not — as I had unthinkingly assumed — in subsidiary traditions, but parallel ones? And that the only thing unique, superior to all others, and especially important in my tradition — was that I was in it? Was centrality really a relative matter?’

— Joanna Russ, How to Suppress Women’s Writing

— — — —

a beautiful rain from Ireland in the mail (on the current issue of The Green Book)

— — — —

The America that never existed is always more powerful in our imagination than that which was there and now isn’t.

This American sentence is far more frightening than its English source : ‘The England that never existed is always more powerful in our imagination than that which was there and now isn’t.’

— David Southwell (who is not responsible for my détournement)

http://folklorethursday.com/?p=970

— — — —

‘If, as a Black, Southern woman reader, I can find a way to connect to so many stories by other writers whose works don’t center me, then I know others can do the same when they encounter works that place them on the margins’ — Sheree Renée Thomas, in Locus

— — — —

Sailing, Creeping, Boring — William S. Reese

— — — —

There is an exhibition of early ownership marks and other aspects of the physical evidence of reading, at the RAI Library in Barcelona La vida privada dels llibres del CRAI Biblioteca de Reserva, Barcelona https://crai.ub.edu/sites/default/files/biblioteques/Reserva/expo/index.php

— — — —

The Temporary Culture website is fully functional and allows readers to purchase all current books of the press — including the new edition of The Private Life of Books — and a selection of other books and material of interest. https://temporary-culture.com

# # #

Thank you for reading. Happy New Year!

Henry Wessells

— — —

— — —