Moby-Dick and American Literature of the Fantastic ; or, Bound for the South Seas

Prologue

This is a crackpot theory with a kernel of truth. It requires some minimal familiarity with the works of H. P. Lovecraft and Herman Melville. It took shape as I re-read Moby-Dick for the first time in decades in January 2016, and I expounded it at the California Antiquarian Book Fair in February 2016, to my friend Bill Reese, a supreme Melville collector and the greatest Americana dealer of his generation. Great reader though Bill was, he had never read any H. P. Lovecraft and so he greeted my geste with a glazed look that means, as any performer will attest, you have lost your audience. On another occasion, an eminent Melville scholar responded with a Jupiterian frostiness. So you have been warned. I performed early versions of it with impromptu embellishments a few times in the interim in bar-rooms and one evening on the patio at Readercon in Quincy, Mass., for Jim Morrow and a few others, in July 2017. This final text was read at Readercon in July 2023. As you will see later, it is necessary to give this chronology.

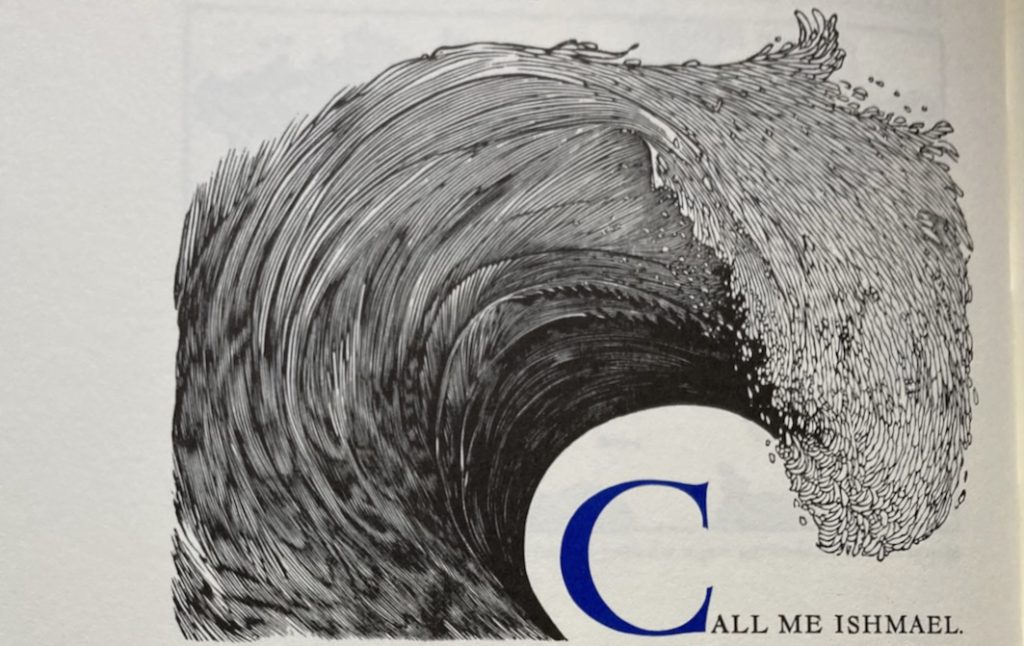

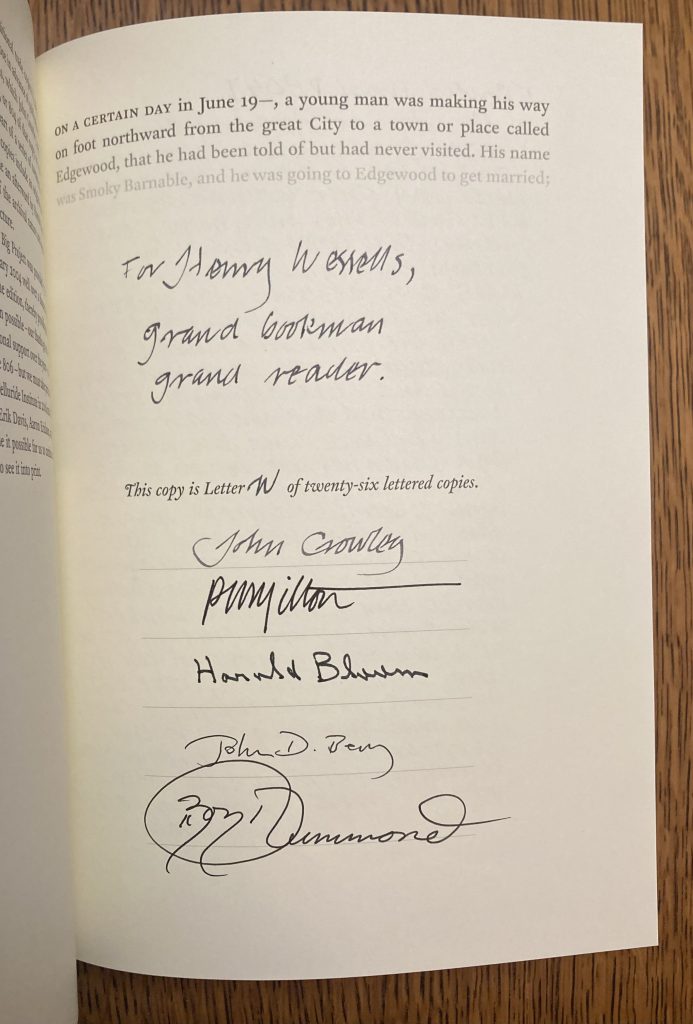

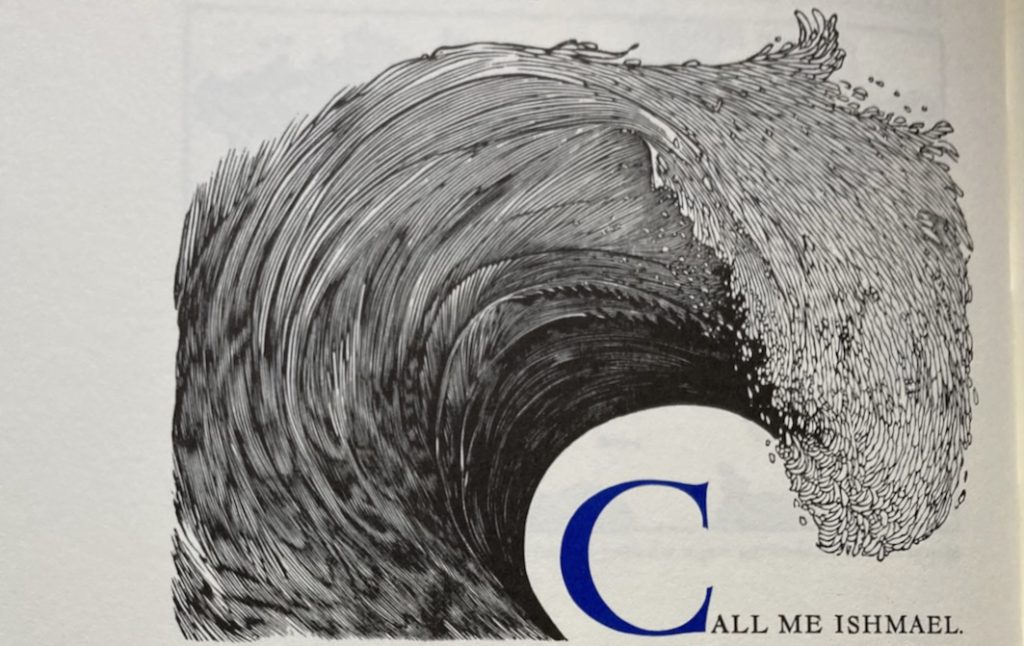

[All citations from Moby-Dick are to the University of California paperback with the illustrations from the Barry Moser Arion Press edition.]

Moby-Dick and American Literature of the Fantastic ; or, Bound for the South Seas

Ernest Hemingway was only half-right : American literature springs from one book, but that book is Moby-Dick (1851).

I

Melville gives for the first time voices to the voiceless, to those who had heretofore been mere furniture of narrative. It is Tashtego, the “unmixed Indian from Gay Head, the most westerly promontory of Martha’s Vineyard” (122), who first names the object of the Pequod’s quest :

“Captain Ahab,” said Tashtego, “that white whale must be the same that some call Moby Dick.” (166)

The cabin boy Pip dances at midnight in the forecastle until a squall arrives and the “jollies” are sent aloft to reef the topsails. “It’s worse than being in the whirled woods, the last day of the year! Who’d go climbing after chestnuts now? But there they go, all cursing, and here I don’t.” (179)

Stubbs berates the elderly Fleece for overcooking his whale-steak and bids him preach to the sharks worrying the carcass alongside the ship. Fleece concludes with a mutter, “I’m bressed if he aint more shark than Massa Shark himself.” (306)

II

Moby-Dick also marks the point where English poetry becomes American literature. To take three examples, here is Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancyent Marinere” transformed :

An intense copper calm, like a universal yellow lotus, was more and more unfolding its noiseless measureless leaves upon the sea. (320)

Melville had earlier named Coleridge and the albatross to assert Nature’s precedence over the English poet. (191)

Chapter 93, the episode of Pip’s loss overboard, takes its title from William Cowper’s poem of madness, “The Cast-away”, and its substance from these verses : “We perish’d, each alone: / But I beneath a rougher sea, / And whelm’d in deeper gulfs than he.”

By the merest chance the ship itself at last rescued him [. . .] Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. (424)

And, of course, it is the “Sea-change / Into Something Rich and Strange” from Ariel’s song in The Tempest, that echoes in Ahab’s words :

This is a pine tree. My father, in old Tolland county, cut down a pine tree once, and found a silver ring in it [. . .] when they come to fish up this old mast, and find a doubloon lodged in it, with bedded oysters for the shaggy bark. Oh, the gold! (445)

So far so good, nothing extraordinary or particularly new about these citations. They are excellent passages. Moby-Dick is also a great and influential novel of cosmic horror.

III

To go ahead for a moment. The revival of interest in Melville during the 1920s is well documented, including a standard edition of his works, and the discovery of the manuscript of Billy Budd (first published in 1924). In France, Jean Giono read Melville and began a translation of Moby-Dick into French, eventually issued in 1939. When the translation was to be reprinted by Gallimard, Giono declined to write the biography his publishers wanted and instead produced a remarkable fantasia, Pour saluer Melville (Paris: Gallimard, 1941). It is a fictional interlude during Melville’s visit to England in 1849 that bears directly upon the impulse leading Melville to write Moby-Dick. Giono evokes a continual struggle within Melville :

Depuis quinze mois qu’il est dans le large des eaux, il se bat avec l’ange. Il est dans une grande nuit de Jacob et l’aube ne vient pas. Des ailes terriblement dures le frappent, le soulèvent au-dessus du monde, le précipitent, le resaisissent et l’étouffent. Il n’a pas cessé un seul instant d’être obligé à la bataille [. . .] s’il saute dans la balinière, s’il chevauche des orages de fer [. . .] il se bat avec l’ange. (38)

Melville’s unceasing fight with the angel, in the momentous night of Jacob where dawn does not come, is Ahab’s struggle. Ahab can recall the domestic joys and tenderness of fatherhood, but once the Pequod sails he is intent and unwavering in his quest of the supramundane real, that which is beyond the barrier. He tells Starbuck :

All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event — in the living act, the undoubted deed — there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by striking through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. (168).

And elsewhere :

How dost thou know that some entire, living, thinking thing may not be invisibly and uninterpenetratingly standing precisely where thou now standest; and standing there in thy spite? (480-1).

IV

H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937) was a native-born Rhode Islander, a cosmic materialist by philosophical inclination, and a writer of fantastic fiction. He lived for some years in exile in New York City. In August 1925, Lovecraft wrote down the plot outline for a story based on a dream from years before, and recasting an earlier tale.

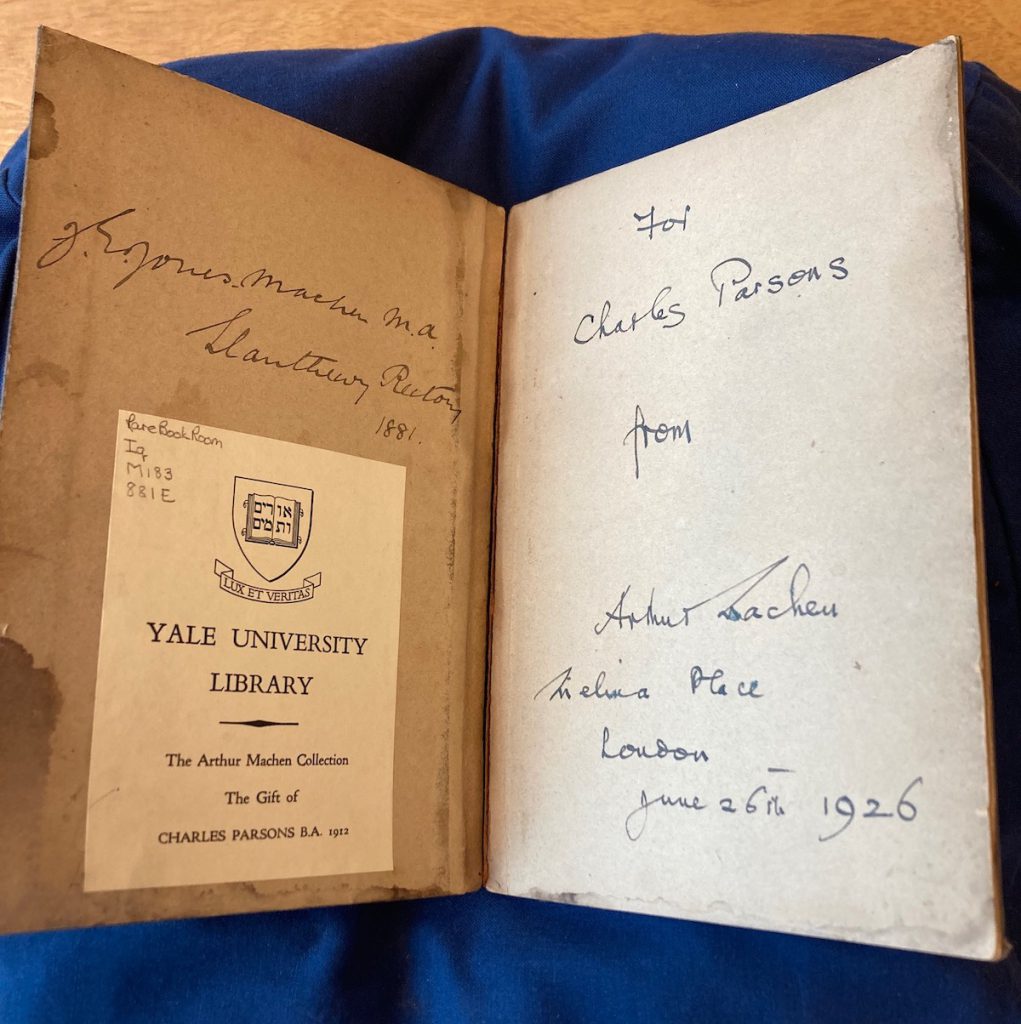

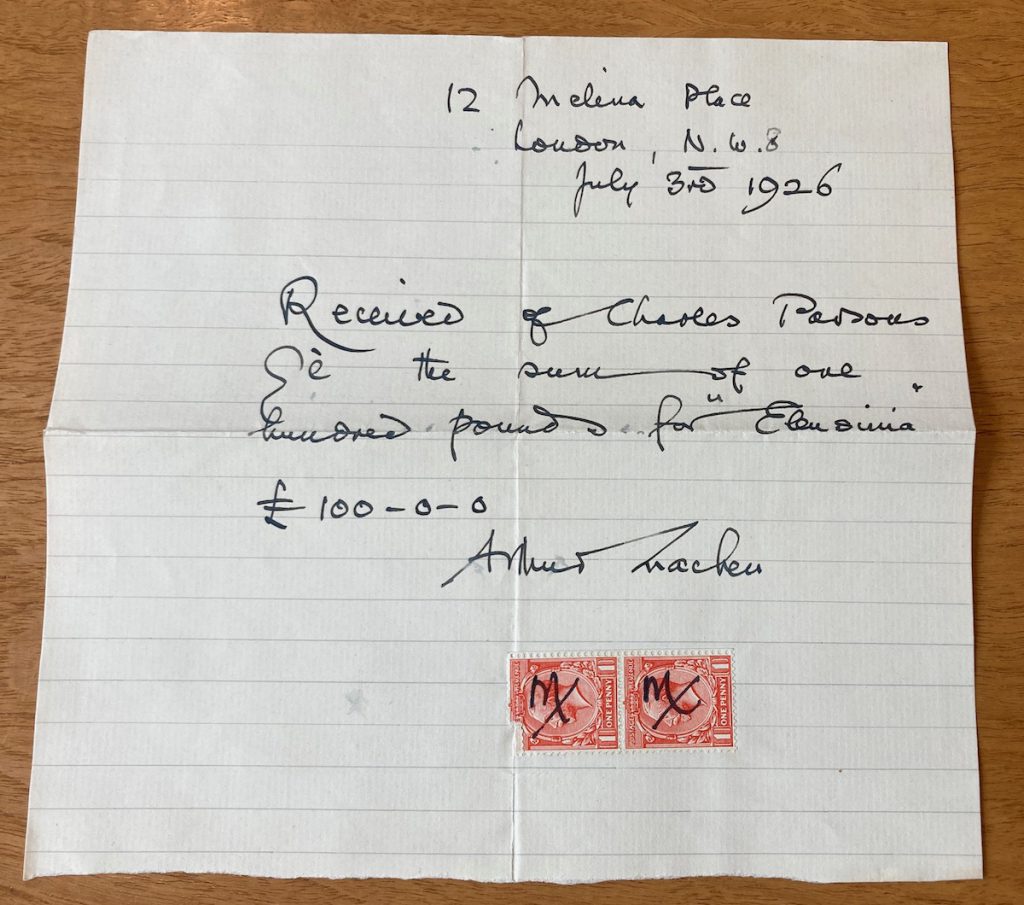

In early 1925 Lovecraft dwelt in an apartment house in Brooklyn, and a neighbor was George W. Kirk, whom he had known since 1922. Kirk was a bookseller who later owned the Chelsea Book Shop on West 8th street in Manhattan. Sometime in the middle 1920s, Kirk gave a copy of Moby-Dick to Lovecraft, who recorded the gift on the book’s fly leaf, and signed his name: H. P. Lovecraft, Esq., Providence, Rhode-Island.

I have examined that copy at the American Antiquarian Society. It has Lovecraft’s fine fanlight window bookplate and bears a pencil accession note on the pastedown: Purchase S. Clyde King, Jr. Aug 8 ’41. (Lovecraft’s Library was dispersed after his death; King was a Providence bookseller). Moby-Dick was rediscovered at A.A.S. in November 2017 (note that date) during a shelf read in the stacks. The book is otherwise unmarked. And yet, and yet.

“Let the owners stand on Nantucket beach and outyell the Typhoons.” (483). In this passage from chapter 109 of Moby-Dick, I hear the origins of a phrase in a later story of Lovecraft’s describing terrible events in rural Massachusetts, “The Dunwich Horror” (written 1928 and published 1929): “some day yew folks’ll hear a child o’ Lavinny’s a-calling its father’s name on the top of Sentinel Hill” (in Tales. New York: Library of America, 2005, page 375).

The horror in question is one of a pair of twins conceived by Lavinia Whateley in congress with Yog-Sothoth, an interdimensional being. Wilbur Whateley, uncouth and stinking, took after his human parent. The other twin did not.

After his return to Providence in April 1926, Lovecraft eventually completed the story he outlined a year earlier. “The Call of Cthulhu” was published in Weird Tales in early 1928. It is a globe-spanning tale of malign influences, primitive cults, and the resurgence of an ancient extraterrestrial being, Cthulhu (pronounced “khlul’-hloo”). In the subsequent decades, Cthulhu has stepped out of the pages of Lovecraft’s story and, like Mary Shelley’s monster, taken on a life of its own.

V

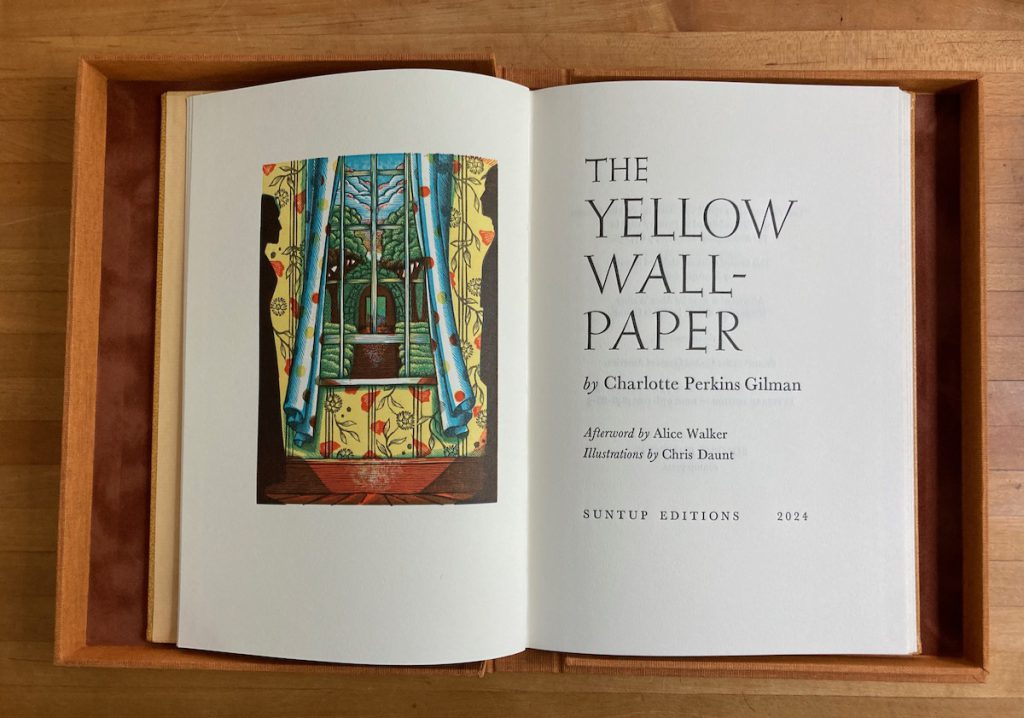

And so to the next step, the ambiguity of pronouns: “There she blows!” Invariably, throughout Moby-Dick. Elsewhere whales are “he”, grammatically male by default, as buttressed by Melville’s cetology and lore of the sperm whale fishery. And yet.

Moby-Dick is the intrusion of these terrible interdimensional forces into the ordinary. So ordinary cetology does not apply, and the white whale is a she-whale. In his last speech, Ahab proclaims, “Toward thee I roll [. . .] still chasing thee, though tied to thee, thou damned whale!” (574-5).

The fated rendez-vous is a hot date in the South Seas : Cthulhu is the spawn of Ahab and Moby-Dick.

Q.E.D.

Author’s Note:

I had written an early version of this essay in the summer of 2017; and then in December 2017, I learned that the American Antiquarian Society holds H. P. Lovecraft’s copy of Moby-Dick (an edition published in Boston after Melville’s death: the copyright notice is in his widow’s name).

Moby Dick or The White Whale / by Herman Melville author of “Typee,” “Omoo,” “White Jacket,” etc.

Boston : Dana Estes & Company publishers, [1892]. American Antiquarian Society copy has bookplate of H.P. Lovecraft. Inscribed: From George Willard Kirk, Esq. H.P. Lovecraft, Esq., Providence, Rhode-Island. Catalog Record #144128.

https://catalog.mwa.org/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=144128

They wrote about the discovery:

14 November 2017

Fun fact: AAS has a copy of Moby Dick once owned by H. P. Lovecraft! A source of inspiration for him, perhaps?

It’s a nice-looking copy too! [with illustrations]

Jean Giono. Pour saluer Melville. Paris: Gallimard, 1941. The passage cited above is from p. 38:

For the fifteen months since he has been at sea, he has been fighting with the angel. It is for him the momentous night of Jacob and the dawn does not come. Hard terrifying wings strike him, raise him above the world, tumble him, seize him again, and smother him. Not for a single instant has the struggle relinquished him. [. . .] when he jumps in the whale-boat, when he rides iron storms [. . .] he is fighting with the angel.

[This is my own translation; in the fall of 2017 (!) it was issued as a NYRB Classics paperback in an English translation by Paul Eprile.]

For George Kirk, see S. T. Joshi & D. E. Schultz, An HP Lovecraft Encyclopedia (Greenwood, 2001; Hippocampus Press, 2004), pp. 137-8.

Moby-Dick was not listed in the first two editions of S. T. Joshi, Lovecraft’s Library (Necronomicon Press, 1980; Hippocampus, 2002), but is recorded as item 651 in the fourth edition (Hippocampus, 2017), “Gift of George Kirk,” with citations to Lovecraft’s letters and essays.

[This essay was first published in Exacting Clam 12 (Spring 2024). All rights reserved]