— — —

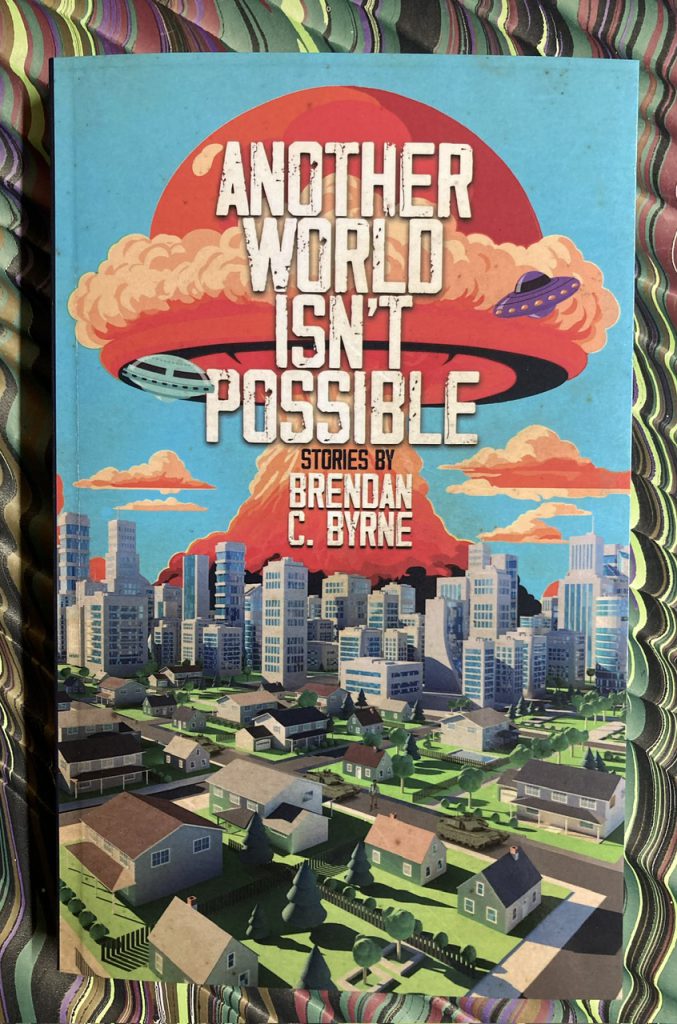

— — —A singular interview with Brendan C. Byrne

— — —

— — —simply messing about in books

— — —

— — —

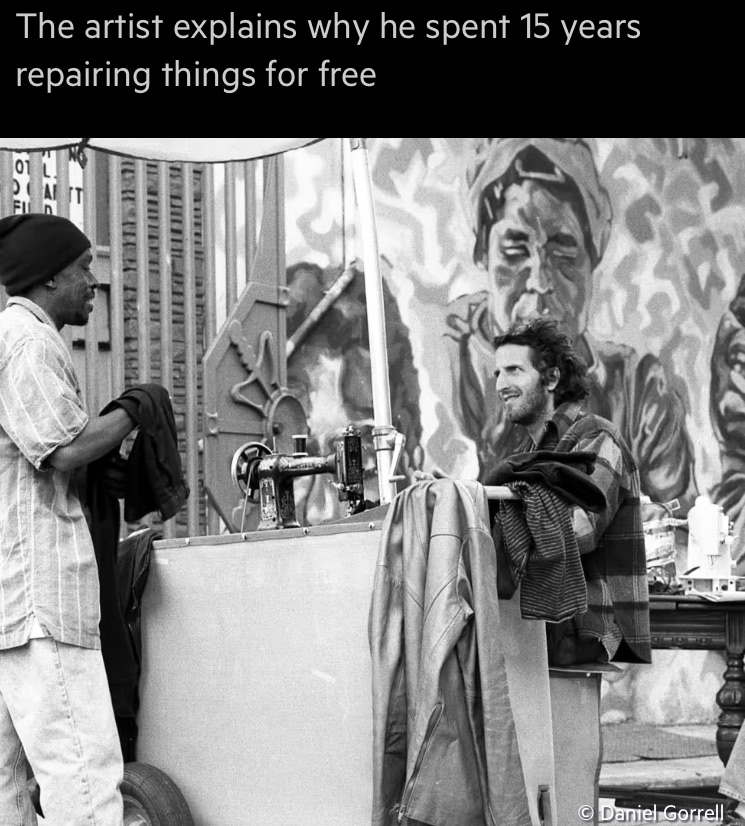

Michael Swaine : ‘What I learnt from mending strangers’ clothes’ / in the FT glossy magazine HTSI

Readers of the ’shelf will recall Michael Swaine as one of the impresarios of the Weedwalk : Book Walk in its two iterations in 2007 and 2009 . Only here will you read about the skill of bookshoeing :

— — —

Your correspondent will be in London for the Firsts Book Fair, from 15 to 18 May, in the Saatchi Gallery, Duke of York’s Square, King’s Road, London SW3 4RY (at the Cummins booth C21). Come say hello.

This means that, for the first time in many years, your correspondent will not be on hand for that glorious annual manifestation of impermanence, Rhododendron Day, which will occur earlier this year. Here is a snap of the work in progress, earlier today : the blooms opened further during the warm day

— — —

Hampstead

— — —

above Haworth, shortly after dawn, 21 May

31 March current reading :

— Winsor McCay. The Complete Little Nemo 1905-1927. / Alexander Braun. Winsor McCay A Life of Imaginative Genius [2014]. Taschen, [2022].

— — —

— Raphael Cormack. Holy Men of the Electromagnetic Age. A Forgotten History of the Occult. W. W. Norton, [2025].

— — —

26 March / homeward bound

— — —

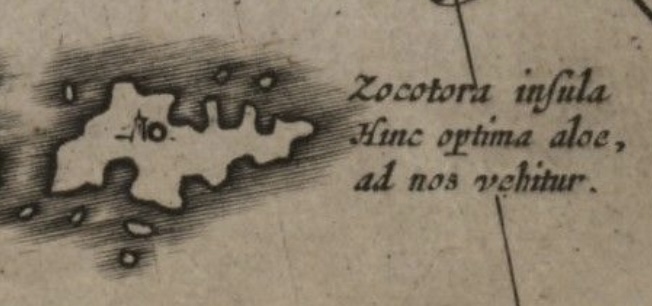

Your correspondent will be far away, and farther, and off line for the next couple of weeks, and will report upon re-entry. [Image above, Zocotora insula, detail from Turcicum imperium, in a Blaeu atlas at the Beinecke.]

Looking ahead to April, the Brontë Society and Tartarus Press will be publishing A Book of Ryhmes by Charlotte Brontë, the manuscript book from 1829 now at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, in a fully illustrated edition with an introduction by Patti Smith, a scholarly essay by Barbara Heritage, and an afterword by Henry Wessells. Publication is scheduled for 21 April (birthday of Charlotte Brontë) and further details will be available at http://tartaruspress.com/bronte-a-book-of-ryhmes.html.

Also in April, the New York Antiquarian Book Fair will be held 3-6 April at the Park Avenue Armory. Come say hello (Cummins booth A3).

— — —

recent reading :

— John Crowley. Little, Big [1981]. Harper Perennial paperback.

Just felt like re-reading it, again.

[added note : an old and trusted friend, carried to the end of the world and back ; always something new arises from the experience of reading Little, Big]

— — —

William Morris on the shelves at Chenati

The library of Donald Judd at at La Mansana de Chinati/The Block in Marfa, Texas, has been catalogued in a neat interactive (and searchable) display. When we visited back in May 2015, I remember being struck by the extent of Judd’s holdings of another artist polymath, William Morris ; the detail above shows most of those holdings. [Thanks to CB for the link.]

https://library.juddfoundation.org/#about

— — —

recent reading :

— Walter Abish. 99 : The New Meaning. With photographs by Cecile Abish. Burning Deck, [1990].

The few books I have published, however, won me no fame. I do not complain of this, anymore than I brag of it, for I feel the same distaste for the “popular author” genre as for that of the “neglected poet” (from “What Else”)

— Philip K. Dick. Radio Free Albemuth [1985]. Mariner pbk. [printed 29 Jan. 2025].

/ re-reading, though I have been thinking about “the tyranny of Ferris F. Fremont” for some time, indeed for much of the past decade

— Peter Straub and Anthony Discenza. “Beyond the Veil of Vision : Reinhold von Kreitz and the Das Beben Movement” [in:] Conjunctions 65, 2015.

— Mark D. Tomasko. Wish You Were Here. Guidebooks, Viewbooks, Photobooks, and Maps of New York City, 1807-1940, from the collection of Mark D. Tomasko. Grolier Club, 2025.

Illustrated catalogue for an exhibition on view through 10 May 2025. The Viele Topographical Map (1865) displays all the watercourses and terrain of Manhattan before the city became part of the built environment.

— — —

commonplace book :

“Elfland as implacable as ever, but now ruthlessly enmeshed in contemporary mortal affairs.” — Mark Valentine, at Wormwoodiana

https://wormwoodiana.blogspot.com/2025/03/henry-wessells-elfland-propositions.html

— — —

books received :

— Michael Swanwick. A Fantasist’s Guide to Venice. Dragonstairs Press, 2025. Edition of 79.

Collection of nine anecdotes about Venice, life and death, and writing, by the author of “The Mask” (collected in Tales of Old Earth).

— Marjan Beijering. Op zoek naar het ongerijmde. Leven en werk van Janwillem van de Wetering (1931-2008). Asoka, [2021].

— — —

‘we are a verb, not a noun’

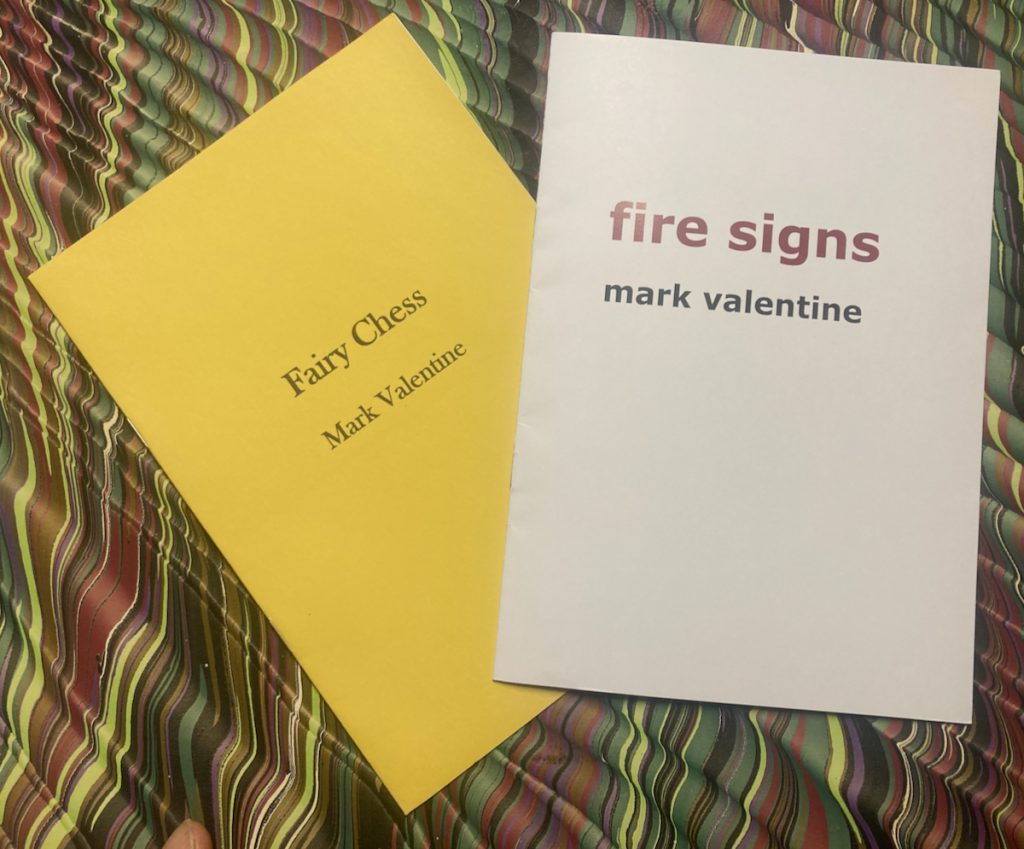

— Mark Valentine. Fairy Chess [cover title]. 2025. Edition of 100.

Collects five poems written in response to words or phrases in the work of Veronica Forrest-Thompson, with allusions to Wittgenstein, Gauloises, libraries, and bicycles.

— —. Fire Signs. [cover title]. 2025. Edition of 100.

Visual record of found poetry from Sunny Bank Mill, Farsley near Leeds.

31 January 2025

in today’s mail

— Conjunctions 83. Revenants : The Ghost Issue. Edited by Bradford Morrow and Joyce Carol Oates. Bard College, 2024.

a big issue, with “An Incident in Monte Carlo”, a fragment or outtake from the forthcoming Wreckage by Peter Straub, new work by Elizabeth Hand, James Morrow, Timothy J. Jarvis, Mark Valentine, Reggie Oliver, and many others.

“Fern’s Room” by Liz Hand is pitch perfect, deftly moving from a gentle rom-com American anglophile country house idyll to a very dark endgame, with clues scattered all along the way.

“Plunged in the Years” by Jeffrey Ford, with a few steps off the path in the woods, gets right to the heart of the American ghost story : time and memory (and childhood).

— — —

recent reading

— Len Deighton. Faith [1994]. Grove Press, [2024].

— Margery Allingham. Sweet Danger [1933]. Penguin Books, [1963].

— Nathan Ballingrud. Crypt of the Moon Spider. Nightfire, [2024].

— Avram Davidson. The Adventures of Doctor Eszterhazy. Owlswick Press, 1990.

— — —

books wait for their readers

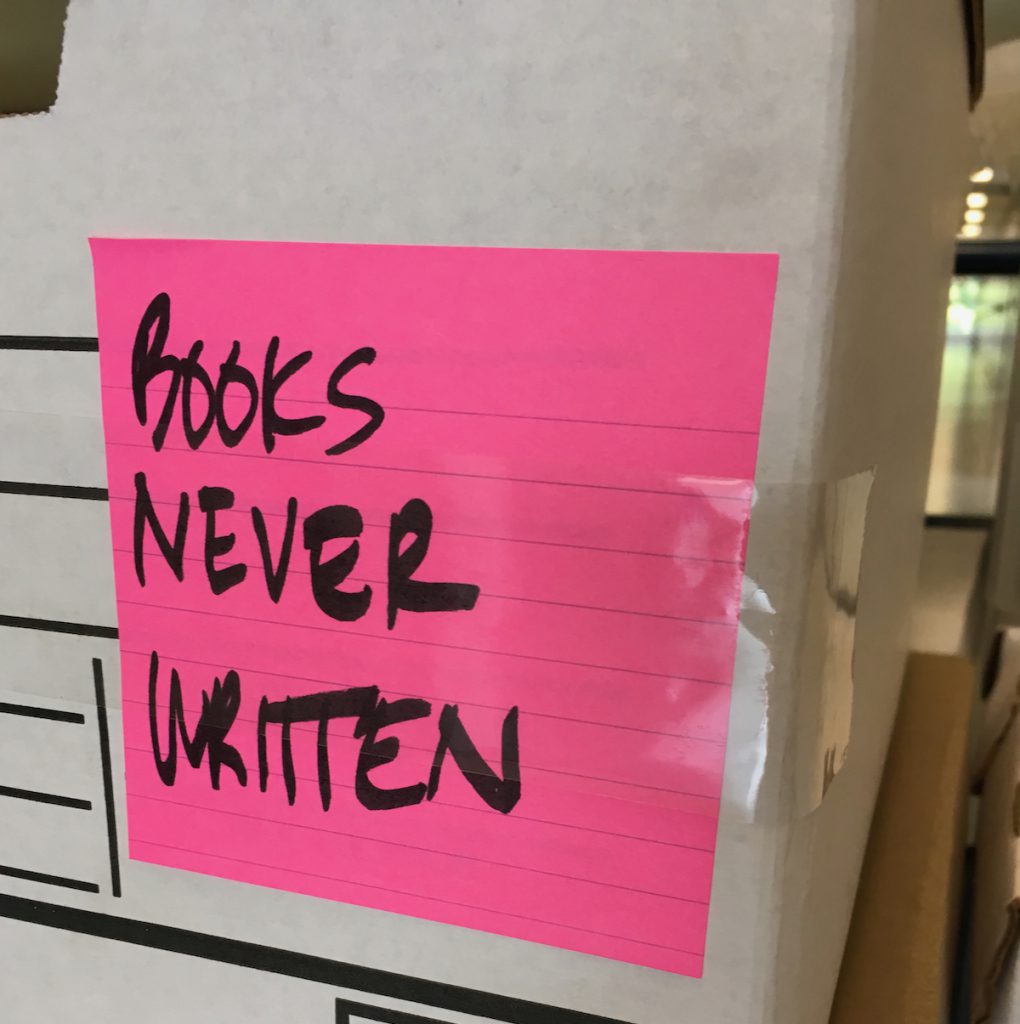

All antiquarian booksellers have a shelf of what Bill Reese called ‘intractables’ : things that sit on a shelf and seem unsaleable, or just beyond the grasp of one’s understanding, or, indeed, actively resist the efforts of the cataloguer with what M. R. James called the ‘malice of inanimate objects’. And then, suddenly, one finds a new perspective, or works with someone who has the key, and the door unlocks. I am fortunate to have experienced this a few times in my career. To watch this phenomenon in real time is one of the delights of the profession.

The question of whether or not books wait for their writers is trickier to answer. This is a question of a different order. I would say yes, on balance, but one feels the clock ticking, and the list of books not written is very long.

— — —

‘to escape the straitjacket that had been science fiction’ — Paul Kincaid

an excellent essay by a clear-eyed critic ringing the changes on Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions anthologies then and now :

http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/who-is-in-danger/

— — —

Eighteen Years of the Endless Bookshelf

Last week marked eighteen years of ‘simply messing around in books’ and reporting the pleasures on this website. It is still fun and so I will continue to note interesting books, curious passages, announcements, occasional snapshots, and digressions.

— — —

an Endless Bookshelf quiz

Who is the Widmerpool ?

— from your year(s) at school or university

— of your chosen field or profession

— observed recurringly elsewhere

/ wrong answers accepted

/ bonus points for naming your favorite book in ‘A Dance to the Music of Time’

— — —

4 January 2025

early in January, and it is already a good year in books, having just received two long-awaited titles in this week’s mailbag

Billy Budd at 100 (continued)

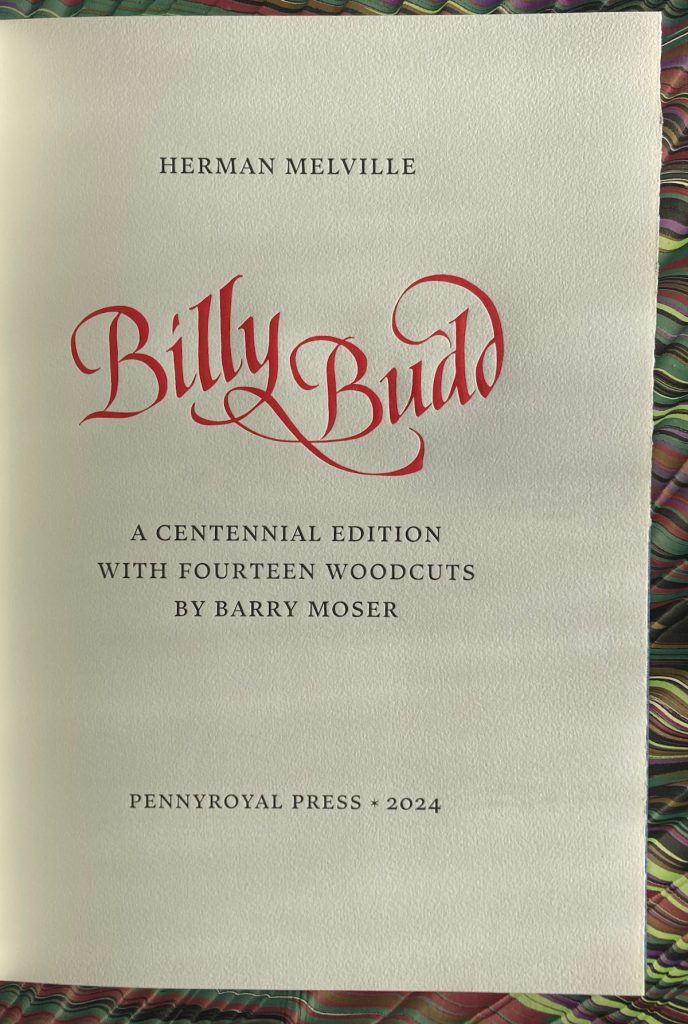

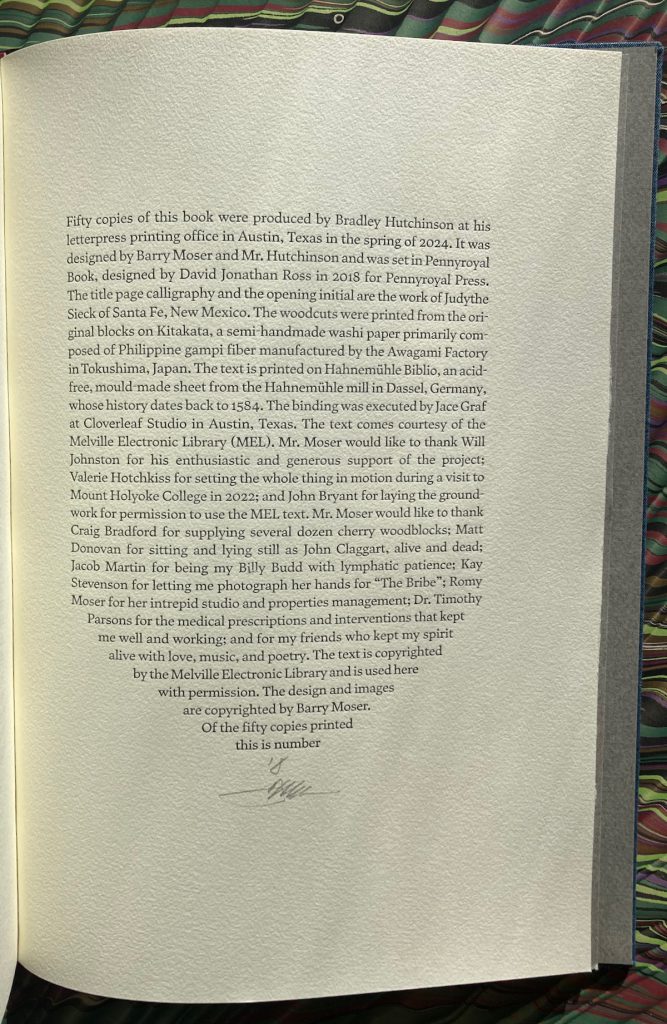

— Herman Melville. Billy Budd. A Centennial Edition with Fourteen Illustrations Cut in Wood by Barry Moser. Pennyroyal Press, 2024. Edition of 50 copies signed by the artist.

A spectacular new large format edition of Billy Budd Sailor (An Inside Narrative) — as the half-title names the book. The text of the novella is set from the Melville Electronic Library, with original woodcuts by American master Barry Moser.

— — —

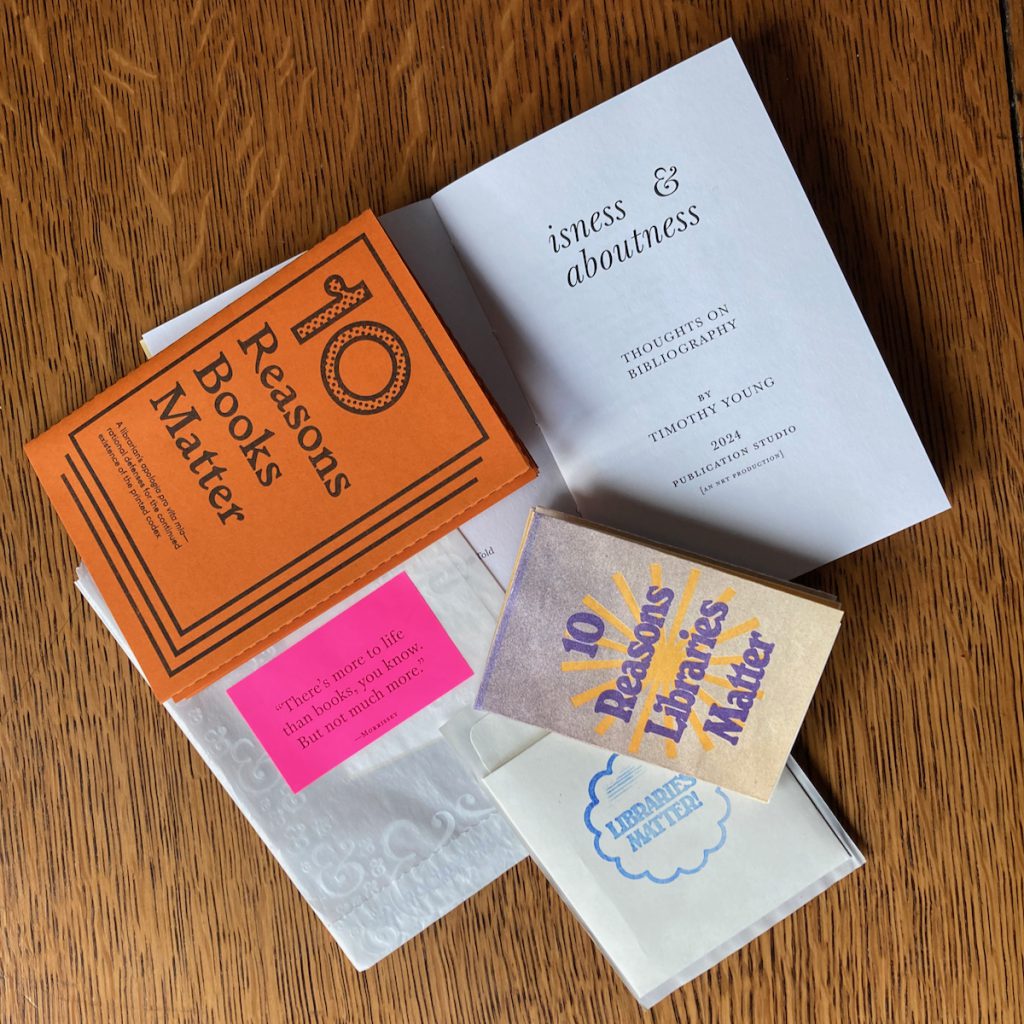

— Timothy Young. Isness & Aboutness. Thoughts on Bibliography. Publication Studio, 2024.

With two single sheet ’zines, printed rectos only :

— 10 Reasons Libraries Matter, 2021.

— 10 Reasons Books Matter, [2015].

Isness & Aboutness is a really great essay on thinking about books and thinking about the world (it is the text of Tim’s Sandars lecture at Cambridge University in November). He cites Donald McKenzie to good effect, on bibliography as

the only discipline which has consistently studied the composition, formal design, and transmission of texts by writers, printers, and publishers; their distribution through different communities by wholesalers, retailers, and teachers; their collection and classification by librarians; their meaning for, and — I must add — their creative regeneration by, readers [. . .] no part of that series of human and institutional interactions is alien to bibliography

His essay moves beyond McKenzie’s assertion to identify new modes of bibliography and to assert the primacy of bibliography as a means of uncovering what books are and what they do in the world. Highly recommended.

— — —

snow day, 11 January 2025

— — —

great blue heron flying low over the silvered mere

alighting on the ice beside a stand of reeds

in the distance, the pulaski skyway

/ from the train window this morning [16 January]

/ file under : extreme commute

— — —

the snow-rhododendrons of Montclair-Himalaya, 21 December

— — —

good morning from the swamps :

view from the glaucous window of a becalmed train, 2 December

/ file under : extreme commute

Readers of the ’shelf and friends in the New York area are invited to an event and presentation, this year honoring PEDRO PONCE, the winner of the Second Tom La Farge Award for Innovative Writing, Teaching and Publishing

It will be held on Friday 11 October 2024, from 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m., at the Ground Floor Gallery of the Grolier Club, 47 East 60th St..(between Madison and Park aves.), NYC, NY 10022.

Pedro will be interviewed, discuss the writing of Tom La Farge, and read from his own work.

This annual award in the amount of $10,000 is designed to encourage and foster literary activity that combines serious play, imagination, erudition and innovative practice. To learn more about the Tom La Farge Award :

https://www.thetomlafargeaward.com/

Refreshments will be served and the doors open at 6:30 pm.

The event is free and open to the public but seating is limited so please RSVP to : Wendy Walker, wwalker377@gmail.com

We look forward to sharing an evening of wonderful writing with you!

Wendy Walker

& the Tom La Farge Committee :

Corina Bardoff

Daniel Levin Becker

Sam Goodman

Michael Kowalski

Eliza Martin

Philip Ording

posted on behalf of the Committee by

Henry Wessells

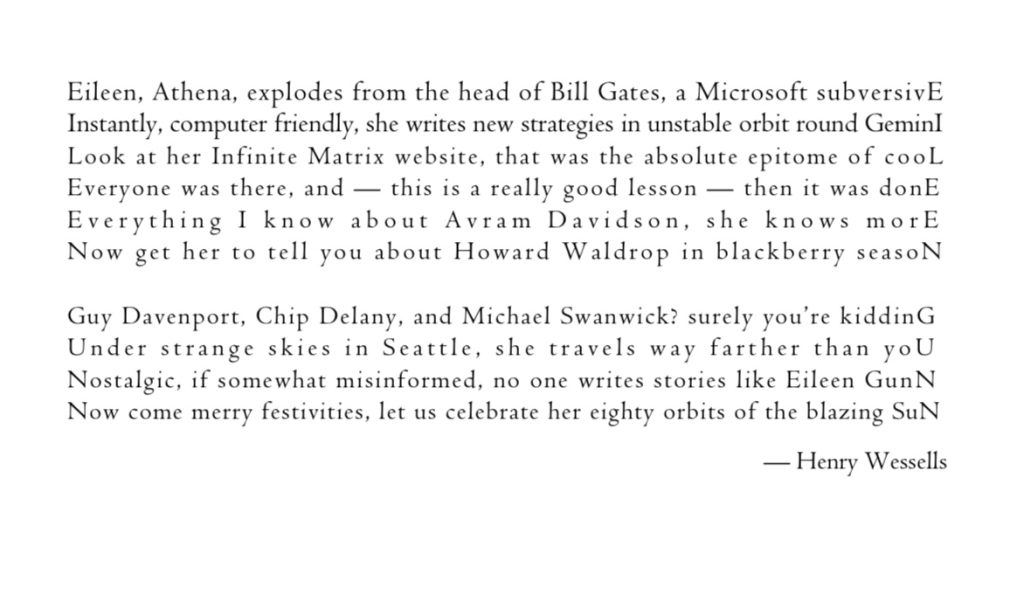

Zagava Books will be publishing Another Green World, a collection of short fiction expanded from the 2003 work with the same title and adding two previously uncollected stories. The book will be available in two states, a narrow format paperback and a numbered hardcover. Another Green World is in production for late spring 2025 and can be pre-ordered here :

https://zagava.de/shop/another-green-world

The table of contents includes the following stories :

Of the first edition, Guy Davenport wrote,

“If you don’t believe in magic, read Henry Wessells and find out how wrong you are.”

Mark Valentine writes : “Henry Wessells delights in books and mysteries and writes with a zest for the arcane and a talent for the oblique and surprising.”

Zagava produce beautiful books and I am delighted to join the ranks of their authors.

afternoon sun in Amsterdam, Leidseplein

— — —

The Endless Bookshelf will be filing despatches from Amsterdam and environs during the week of the A.I.B congress (words and images dropped in here as found).

— — —

things are symbols of themselves / semiotics of Amsterdam

— — —

vegan potato truffle cappuccino

[surprise innovation offered during the medley of the Daalder experience, vegan mode]

— — —

Vondelpark

— — —

Watcher at the edge of the cow pasture, in the Amsterdamse Bos.

— — —

Herengracht

— — —

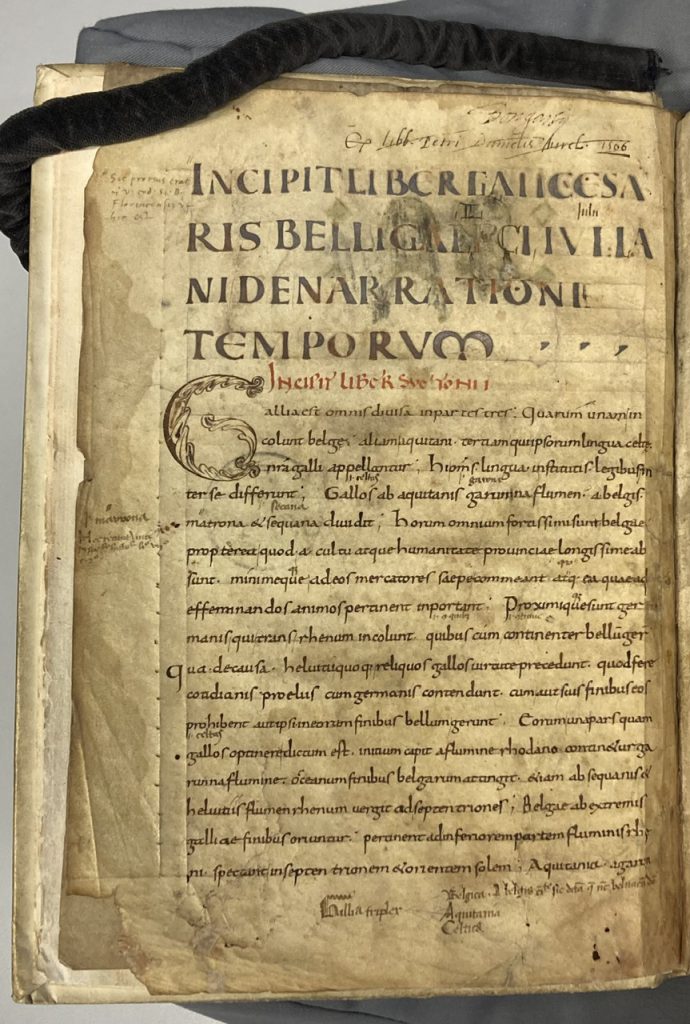

‘Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres’

The earliest surviving manuscript of Caesar’s De bello gallico (On the Gallic War), ca. ninth century CE, at the Allard Pierson collection, University of Amsterdam.

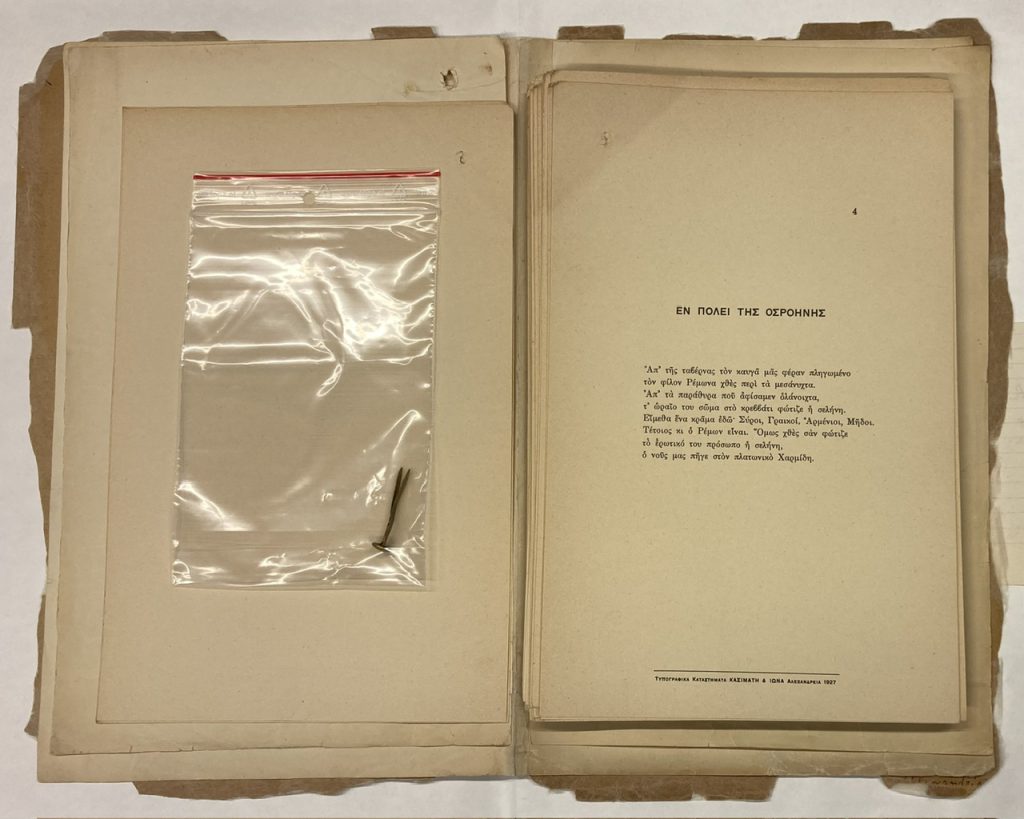

At the other end of the table, a stack of more than 80 ‘feuilles volantes’ (1916-28) of Kaváfis (Cavafy), scattered leaves of his self-published Poems.

— — —

Breestraat, Leiden

— — —

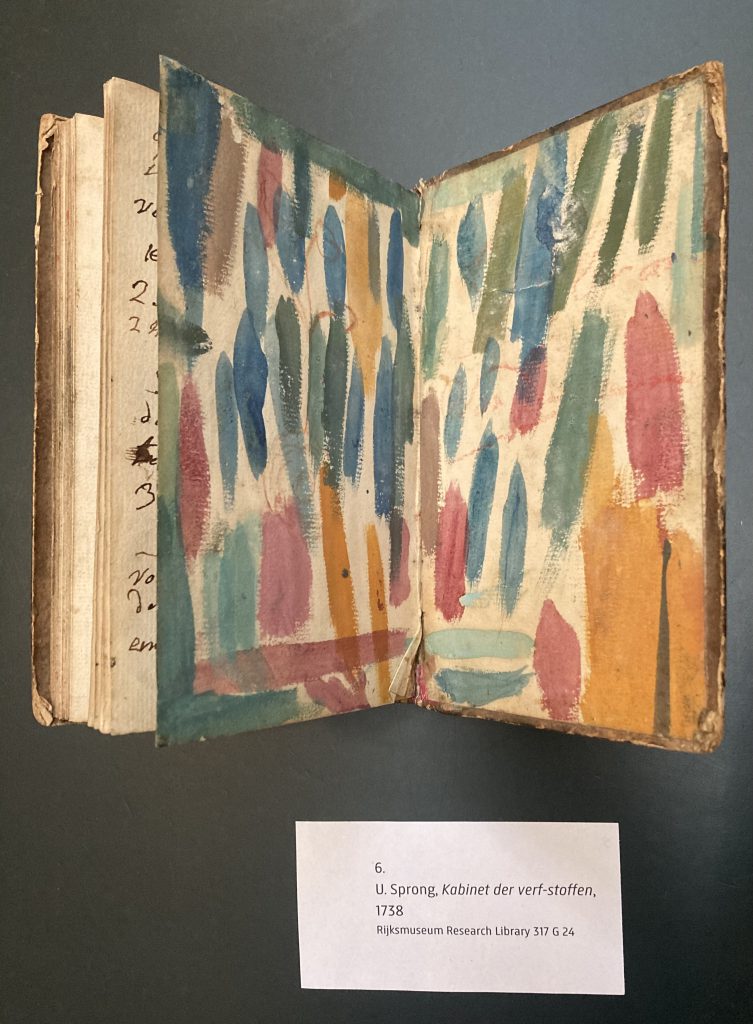

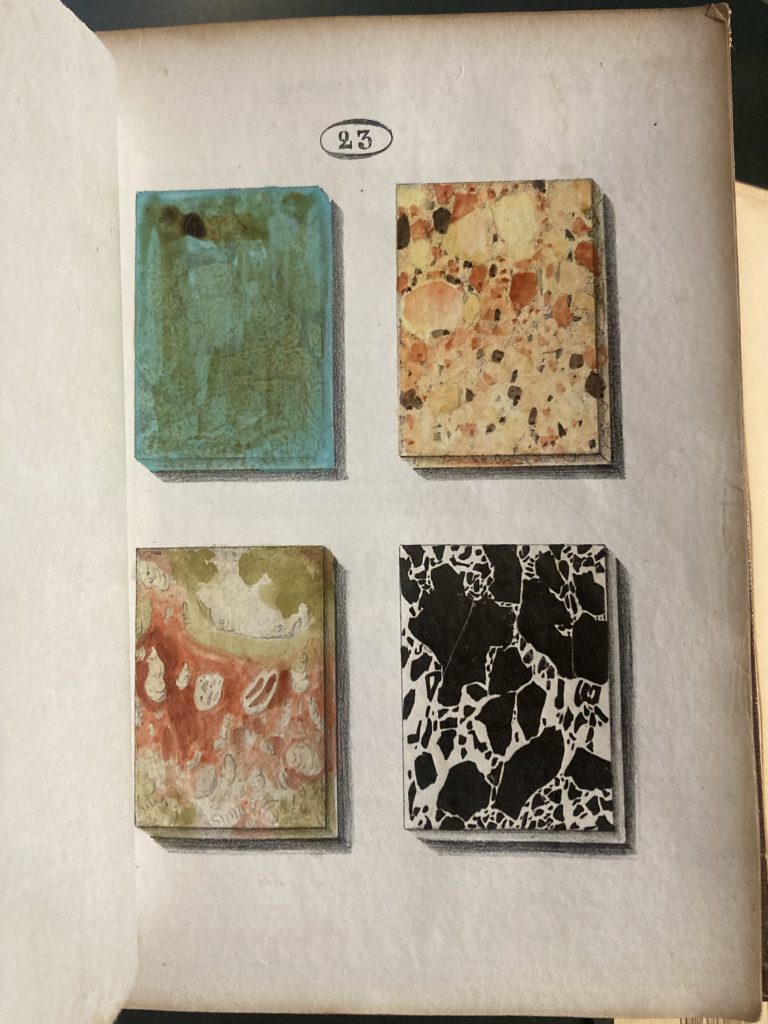

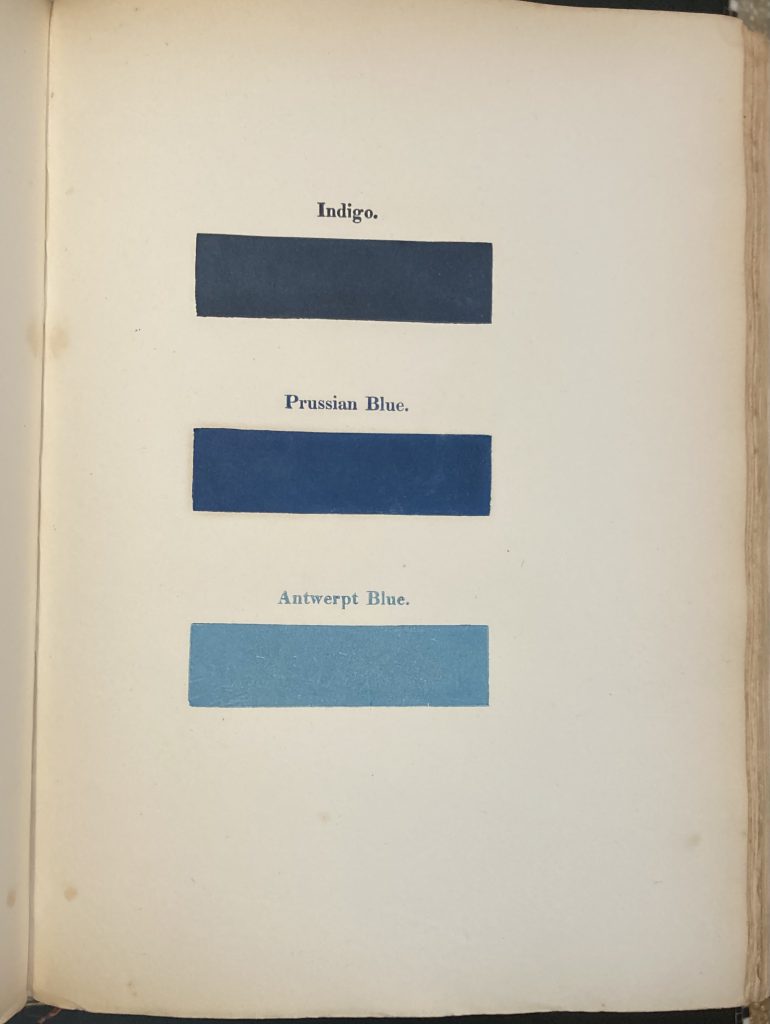

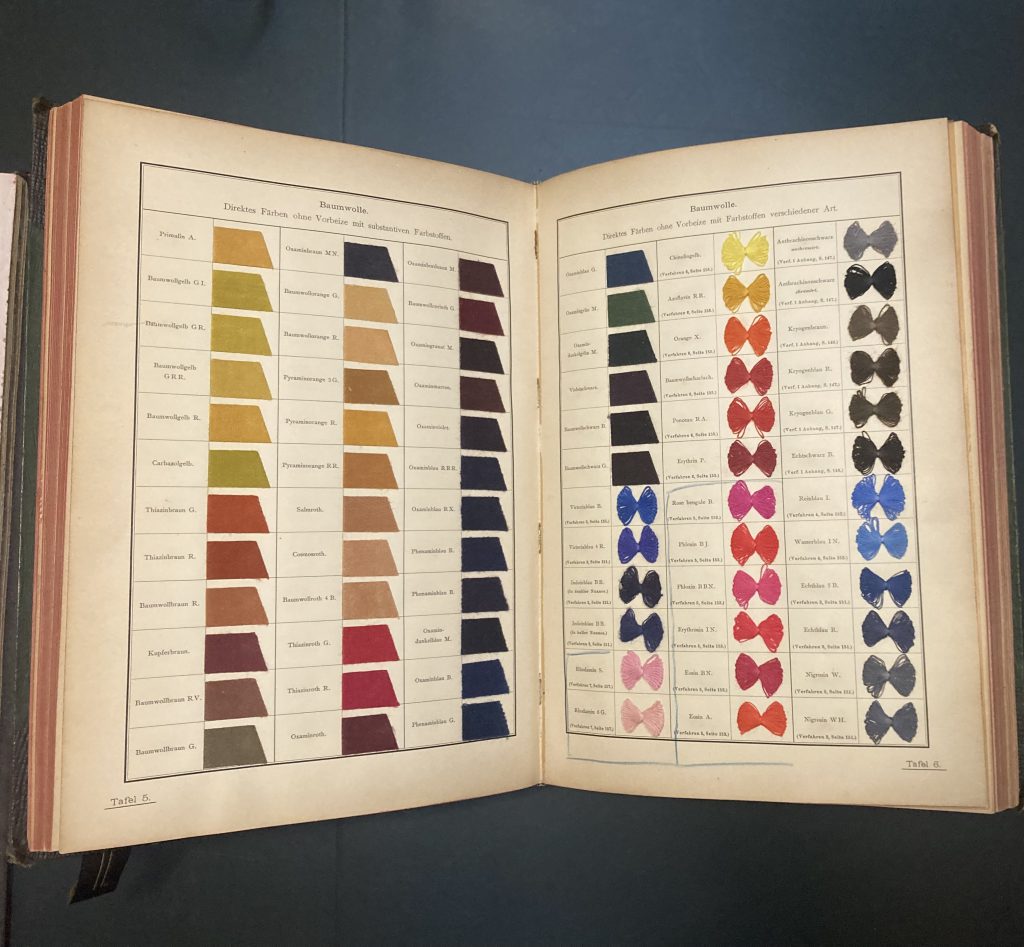

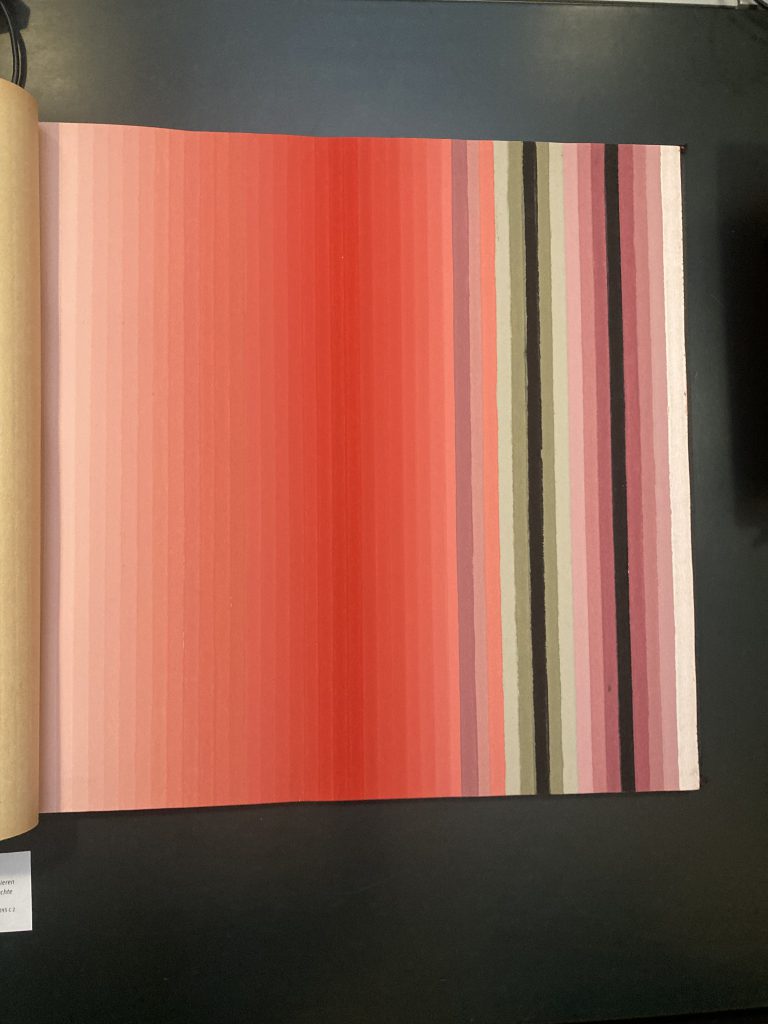

color in the Rijksmuseum library

— — —

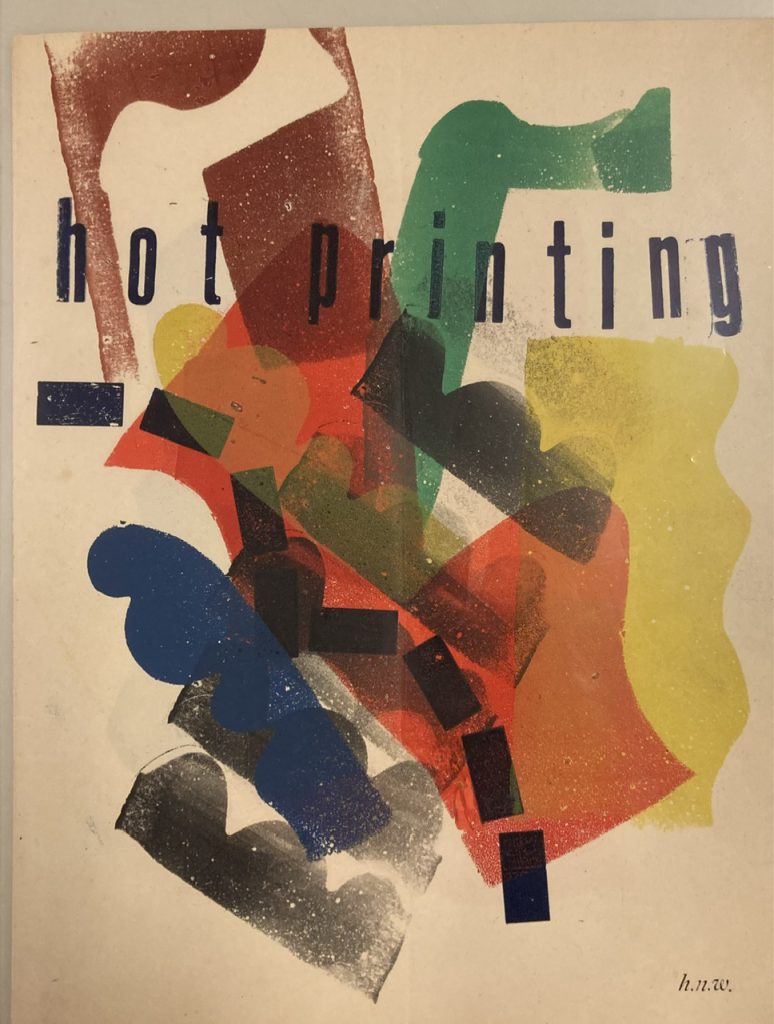

— H. N. Werkman. Hot Printing. [Groningen, ca. 1936]. One of three known copies of a portfolio of prints and poems.

At the Koninglijke Bibliotheek = KB, nationale bibliotheek :

Onze wereld is gebouwd met woorden en gevormd door mensen

— — —

— Vincent van Gogh. Trois romans.

— — —

At the Ritman Library, Keizersgracht 123, Amsterdam.

— — —

Compagnieszaal, West-Indisch Huis, Amsterdam (this is the room where New Amsterdam was planned)

— — —

rainbow at Schiphol

— — —