current reading :

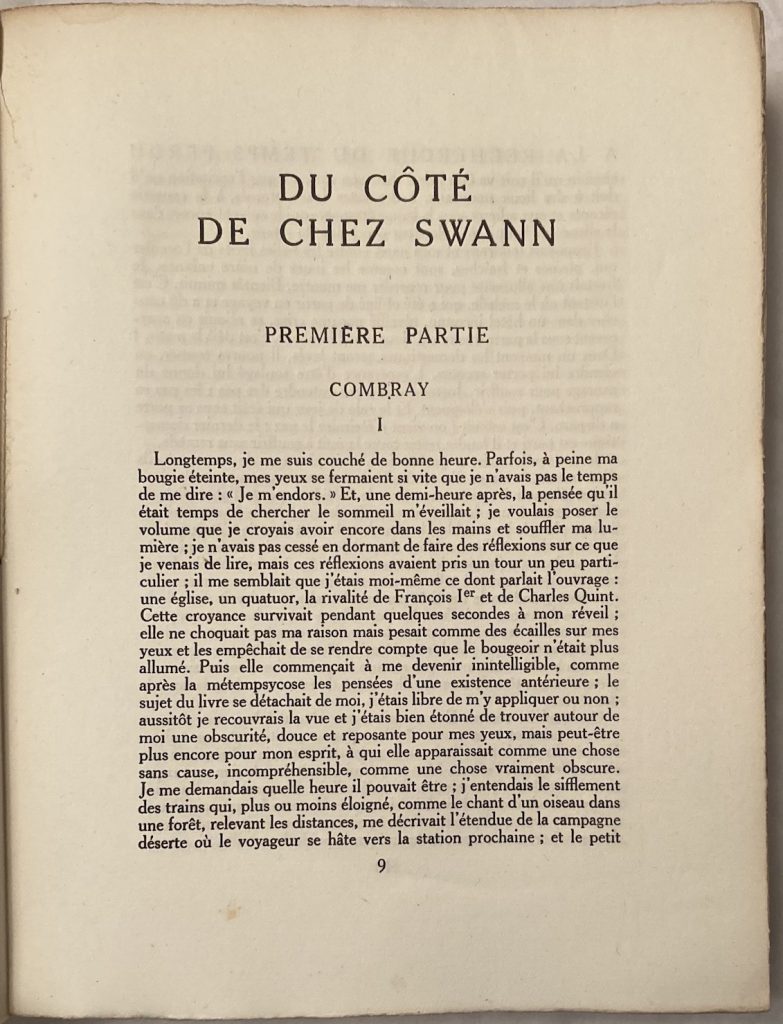

— Marcel Proust. La Prisonnière [1923]. À la recherche du temps perdu III. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. [still climbing the mountain].

— R.B. Russell. Fifty Forgotten Books. Sheffield : And Other Stories, [forthcoming, 13 September 2022].

recent reading :

This was tough going at times, but there was always a remarkable passage or narrative surprise to quicken interest — and what a crack of the whip at end, rooted in earliest beginnings.

— Ngaio Marsh. Night at the Vulcan [1951]. Pyramid Books, [Second printing, December 1974].

— — —

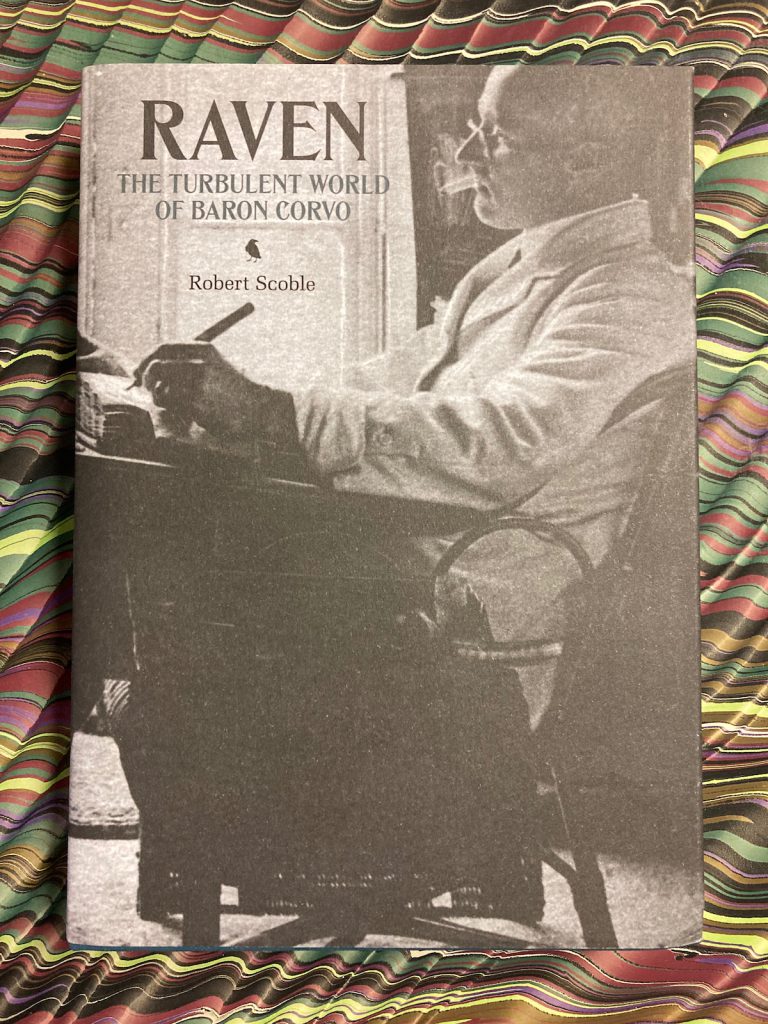

— —. The Corvo Cult. The History of an Obsession. Strange Attractor Press, 2014.

Two well written, engaging, and thoroughly documented overviews of the Frederick Rolfe phenomenon: the people surrounding him and the evolution of the cult of the author.

. . . and everyone is there, in this kinetic Blakean procession, to be animated from Stanley Spencer’s giant painting .

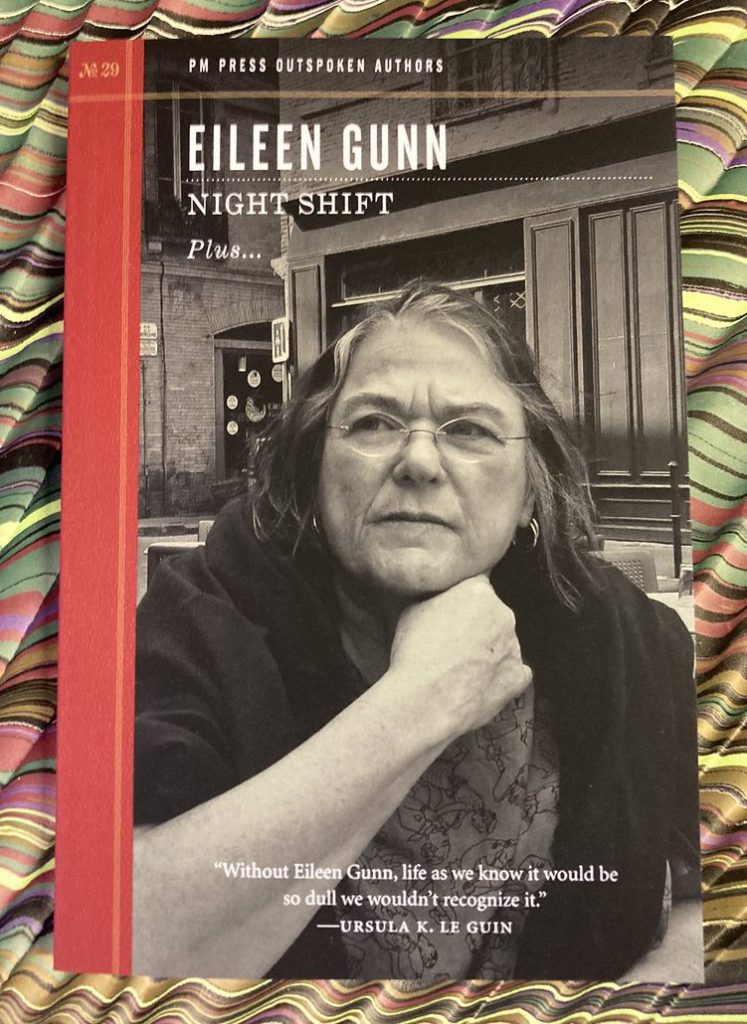

A volume in the excellent Outspoken Authors series, with Terry Bisson’s interview of Eileen Gunn, “I Did, and I Didn’t, and I Won’t”, including this observation about an early job as a advertising copywriter :

“They taught me how to understand subjects I’d never studied and how to work with capitalists without becoming one.”

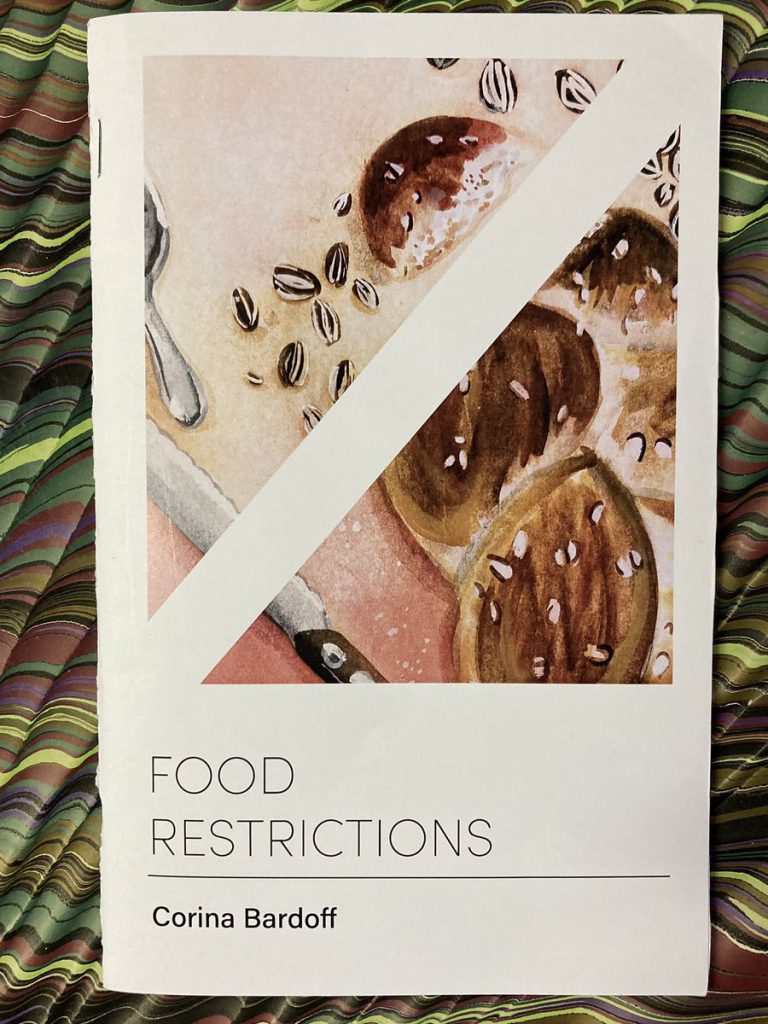

— Corina Bardoff. Food Restrictions. 2020.

— Corina Bardoff. Food Restrictions. 2020.Nimble, funny, literate Oulipian explorations of food and words. [Gift of WW].

Reading this, one has the sense that somehow England will find a way through the present mess.

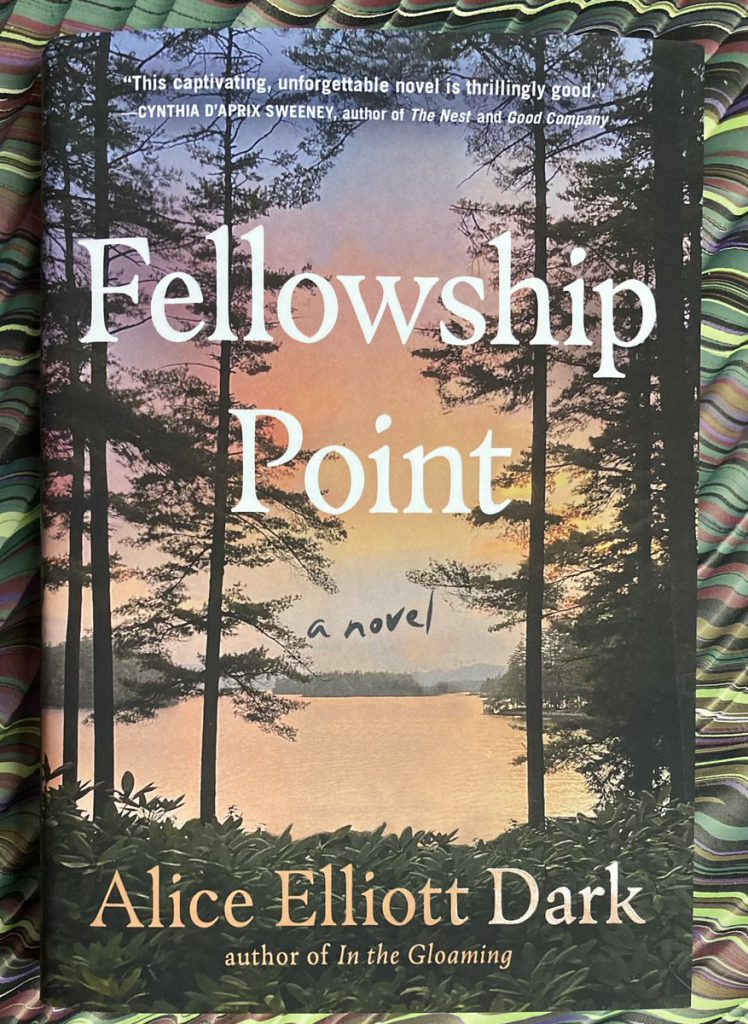

Rich, beautiful exploration of friendship, place, and time (the Maine setting is deeply rooted), with turns and surprises worthy of Dickens ; a notable feminist interrogation of privilege and expectations.

When the Romanian singer started in on « Un dimanche après la fin du monde » I was engaged ; and then the first pages of Chapter 13, The Man Collecting Names is a remarkable sequence of reflections. [Gift of DS].

[Bought in March but misshelved and only found in early June.]

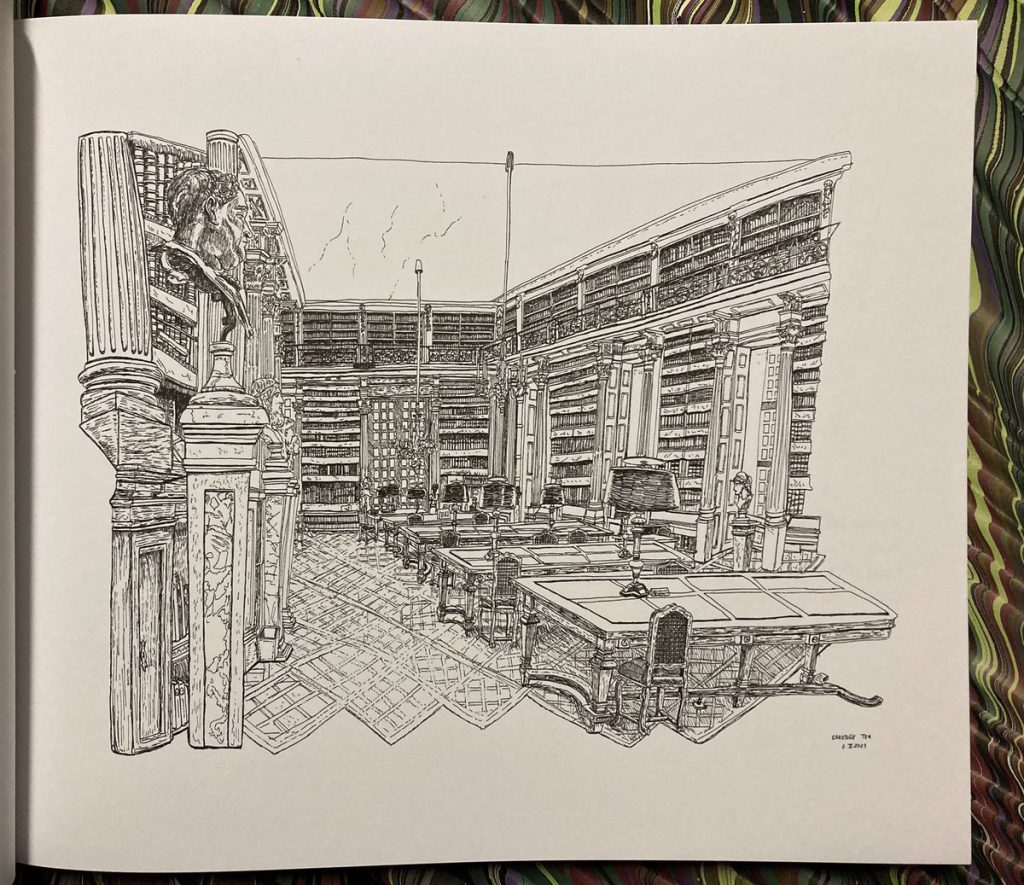

/ above : in the Bibliothèque Mazarine

Collection of nearly two dozen essays, talks, and vignettes about the uncanny, spanning almost the entire career of supernatural writer Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951). The earliest, “The Psychology of Places” (Westminster Gazette, 30 April 1910), seems almost a gloss on his story “The Willows”; the majority of the pieces are from the late 1940s and were often delivered as radio or television broadcasts. Ashley notes Blackwood’s general reticence about any of his own psychic experiences. The essays “collected here reveal his views on the world and the occult, show his diverse reading and experiences, and his appreciation of the experiences of others.”

Illustrated history of a notable twelfth-century manuscript Gospel which survives in its original binding.

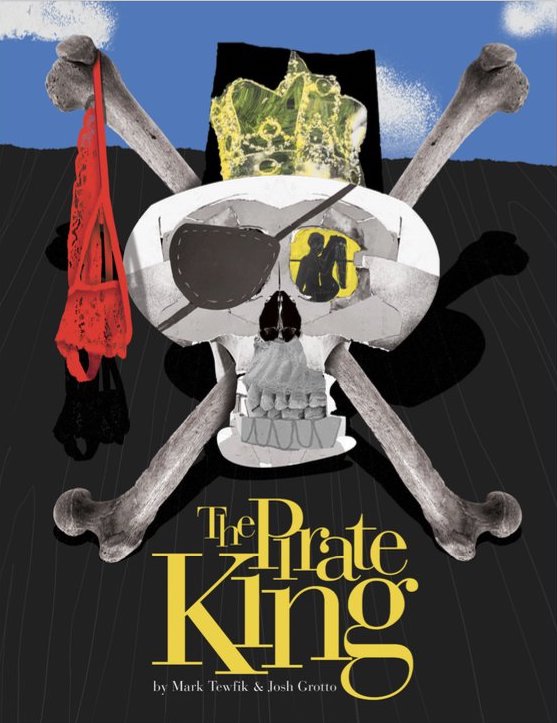

The text of The Pirate King resembles a children’s bedtime tale, while the collage illustrations suggest a very different story. A remarkable tension arises between the visual and verbal references.

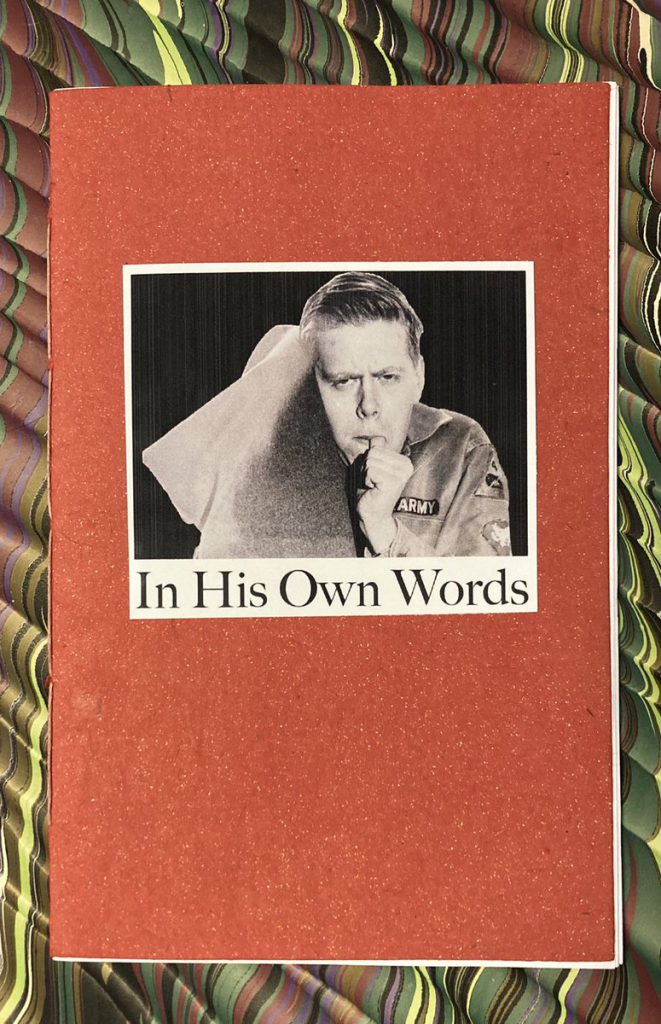

— Michael Swanwick and Gardner Dozois. In His Own Words. Dragonstairs, [2022]. Edition of 60 copies.

— Michael Swanwick and Gardner Dozois. In His Own Words. Dragonstairs, [2022]. Edition of 60 copies.

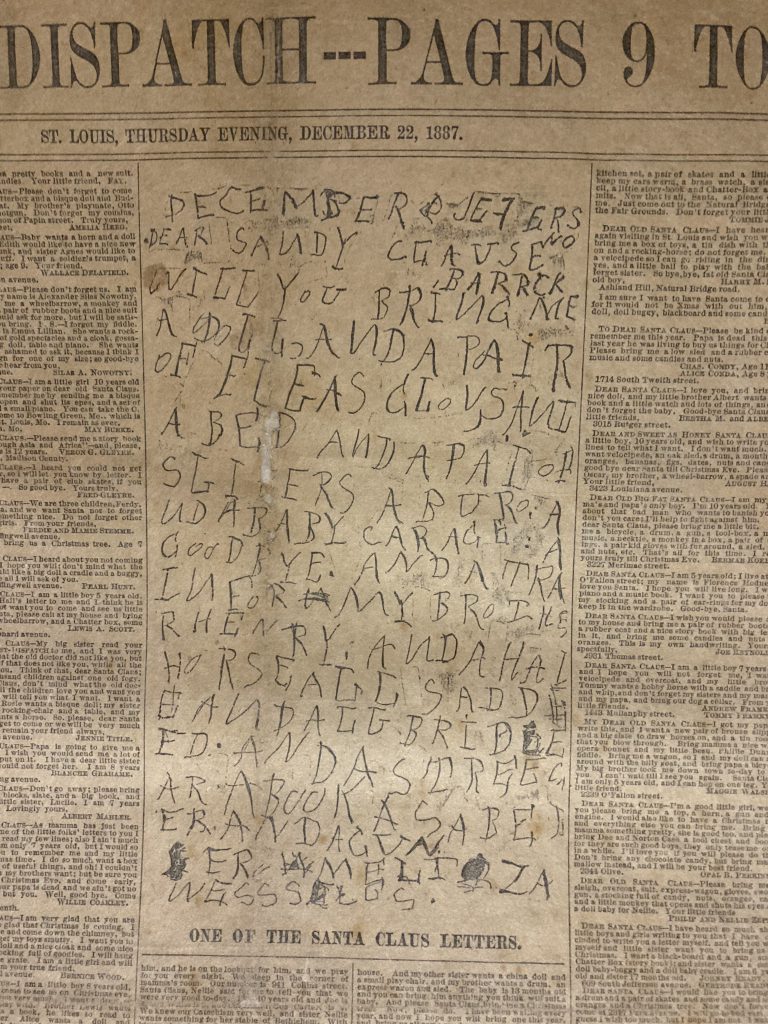

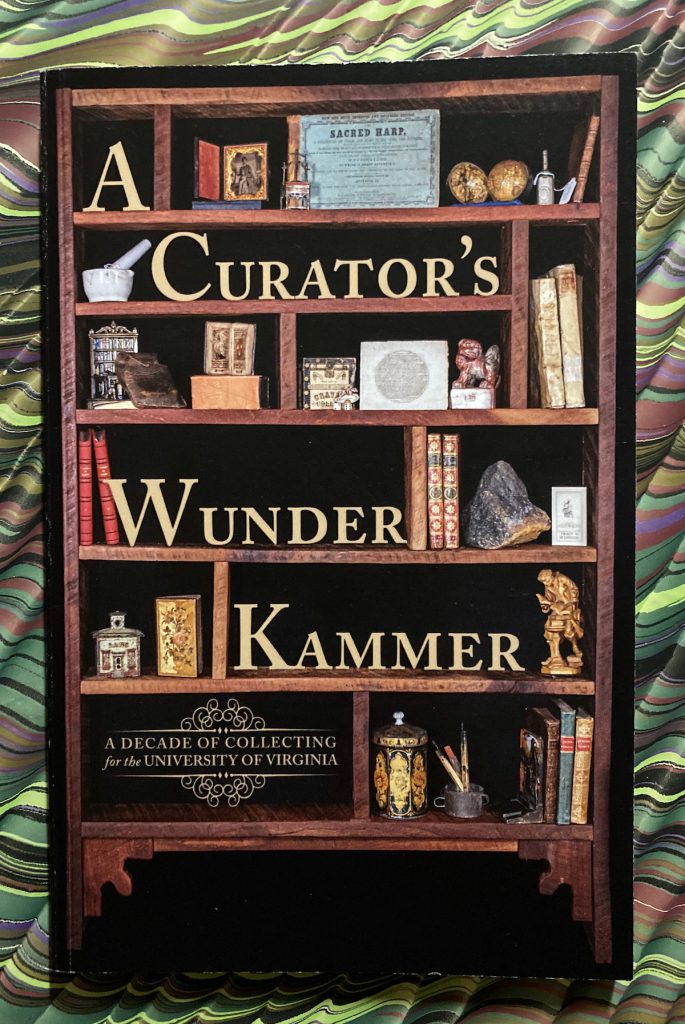

— David R. Whitesell. A Curator’s Wunderkammer. A Decade of Collecting for the University of Virginia. Exhibition Catalog. [Charlottesville: University of Virginia Library], 2022. Illustrated throughout. [iv], 105 pp. Edition of 500 copies [in fact, 310]. $25.00.

— David R. Whitesell. A Curator’s Wunderkammer. A Decade of Collecting for the University of Virginia. Exhibition Catalog. [Charlottesville: University of Virginia Library], 2022. Illustrated throughout. [iv], 105 pp. Edition of 500 copies [in fact, 310]. $25.00.