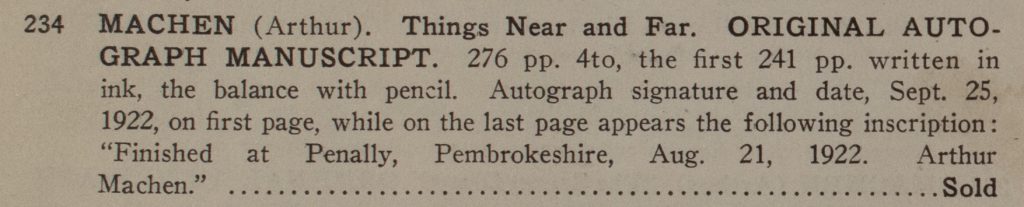

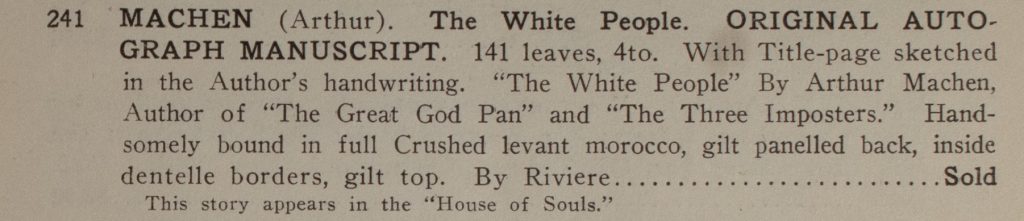

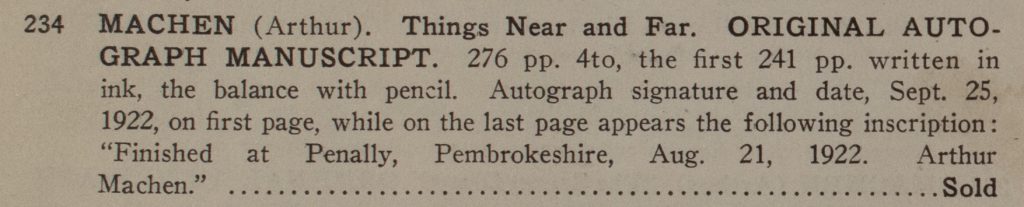

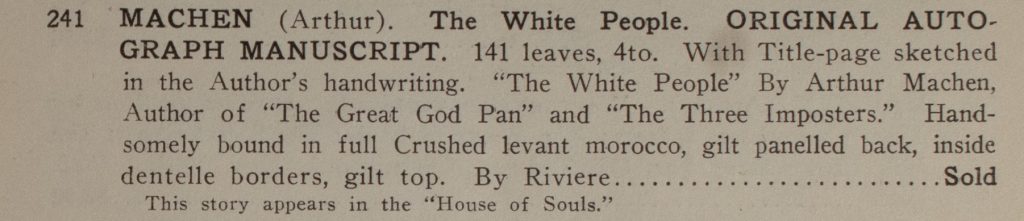

One hundred years ago, on 11 December 1923, Arthur Machen wrote a letter to a young American fan. The letter becomes more interesting with a little context. In the autumn of 1923, New York bookseller Harry F. Marks issued his catalogue 11* and sent out invitations to a display of manuscripts and books of Arthur Machen. The background to this exhibition is notable. In 1922, Machen’s old friend and publisher Harry Spurr had brought manuscripts, proofs, and unpublished materials over to America and sold them to Harry F. Marks, who ran a well-established business for the New York carriage trade, and to Walter M. Hill of Chicago, another book dealer of national reputation. As John Gawsworth notes in The Life of Arthur Machen, “Marks who sold the pick of his collection by private treaty before issuing his 1923 catalogue still had some forty priced items to dispose of there at a total price of some $3,000. [. . .] the ‘boom’ was on”. **

The Life of Arthur Machen transcribes a letter dated 15 October 1923 that had been reproduced as pages three and four of the invitation :

Dear Mr Marks,

You tell me that you are holding an Exhibition of my books and manuscripts at your place in Broadway, New York. I hope your citizens will be interested.

But I cannot help thinking of a visit that I paid this last summer to my old home Llanddewi Vach Rectory in Monmouthshire. I left in September 1887; and had not been there since. The orchards that my father planted had grown into a wood; nothing else was much changed. But the old place brought back to my mind the old days, the days when, quite unknown and solitary, I worked night after night at The Chronicle of Clemendy in the room that looked out on those orchards and above and beyond them to Bertholly on the slope of Wentwood.

It is a far cry from the room at Llanddewi Vach to the Broadway Exhibition.

Yours sincerely,

Arthur Machen

12, Melina Place

London N.W.8

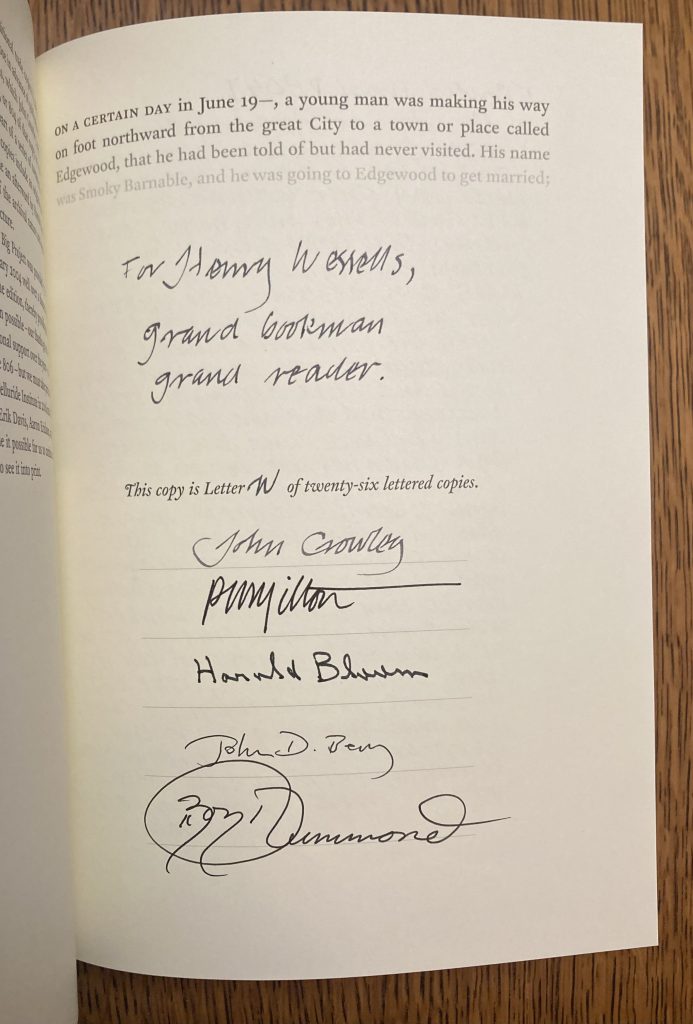

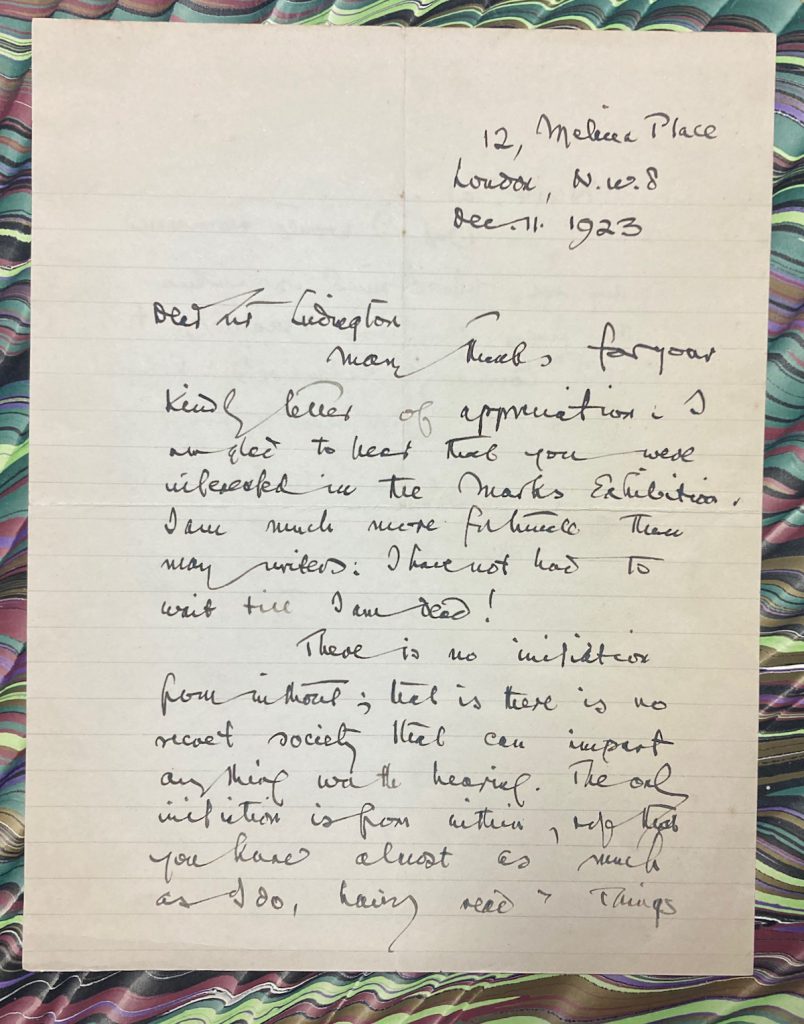

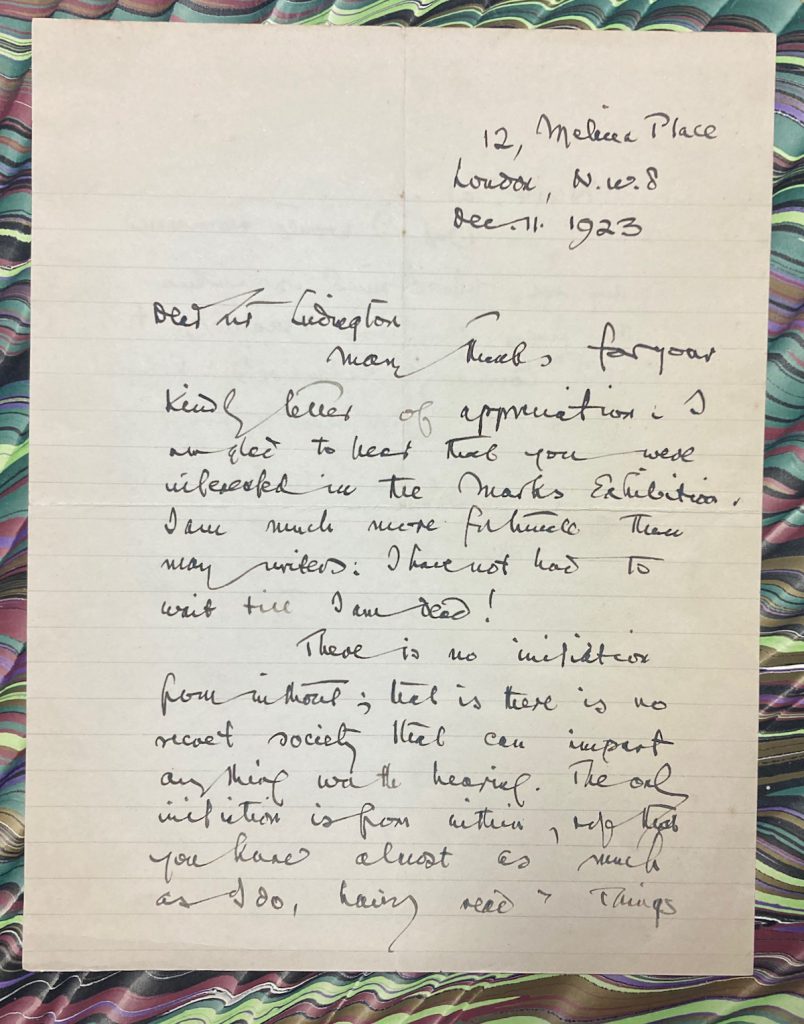

Machen was characteristically diffident about what New Yorkers would make of his work, but the letter from Machen illustrated above shows that the exhibition resonated with some visitors. The recipient of the letter was New York lawyer and bibliophile George Franklin Ludington (1895-1949, Johns Hopkins 1916, Harvard Law 1920), who had written a wistful fan letter to the author after his visit to “a little book dealer (but by no means an inconsequential one) of this city”. Ludington retained a draft or fair copy of his letter, in which he mentions that in his youth in rural Maryland he had “climbed through the brambles that foot of the Hill of Dreams”, and then concludes with a supplication for the secrets bestowed upon Machen by A. E. Waite or others.

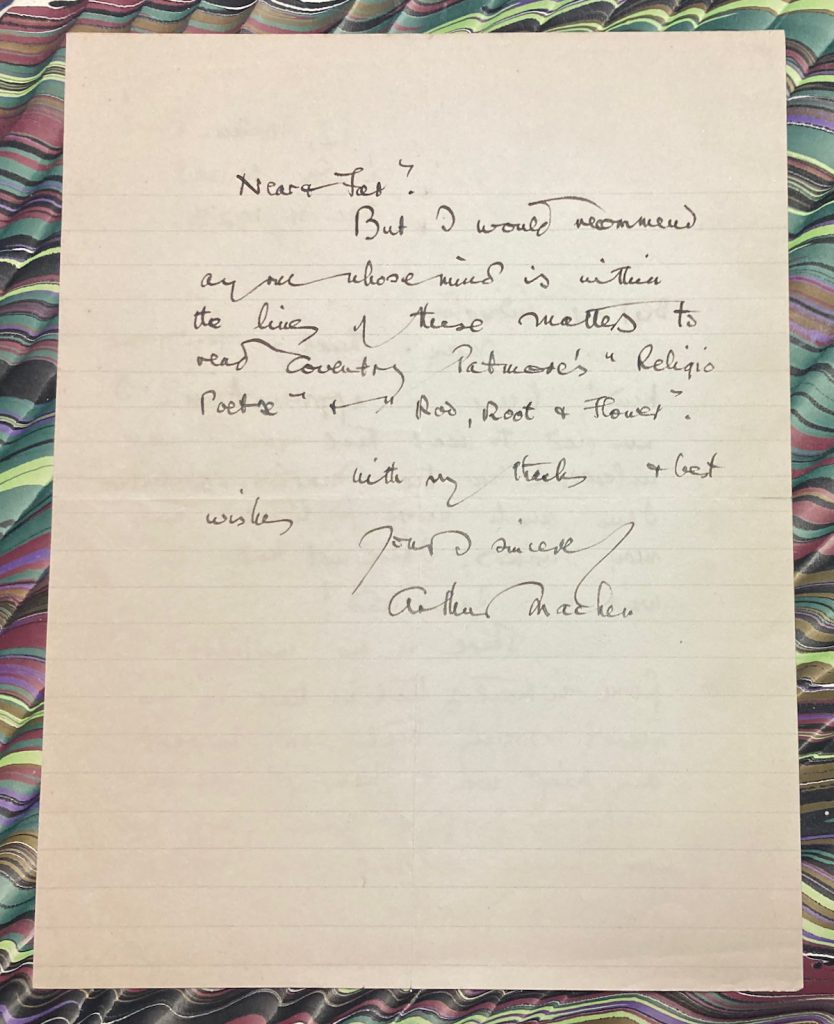

Machen’s response is gracious and tricky and illuminating, and then takes a curious meander into the literary undergrowth. I know the name Coventry Patmore, and so do perhaps a half a dozen others, too; but it is a curious recommendation :

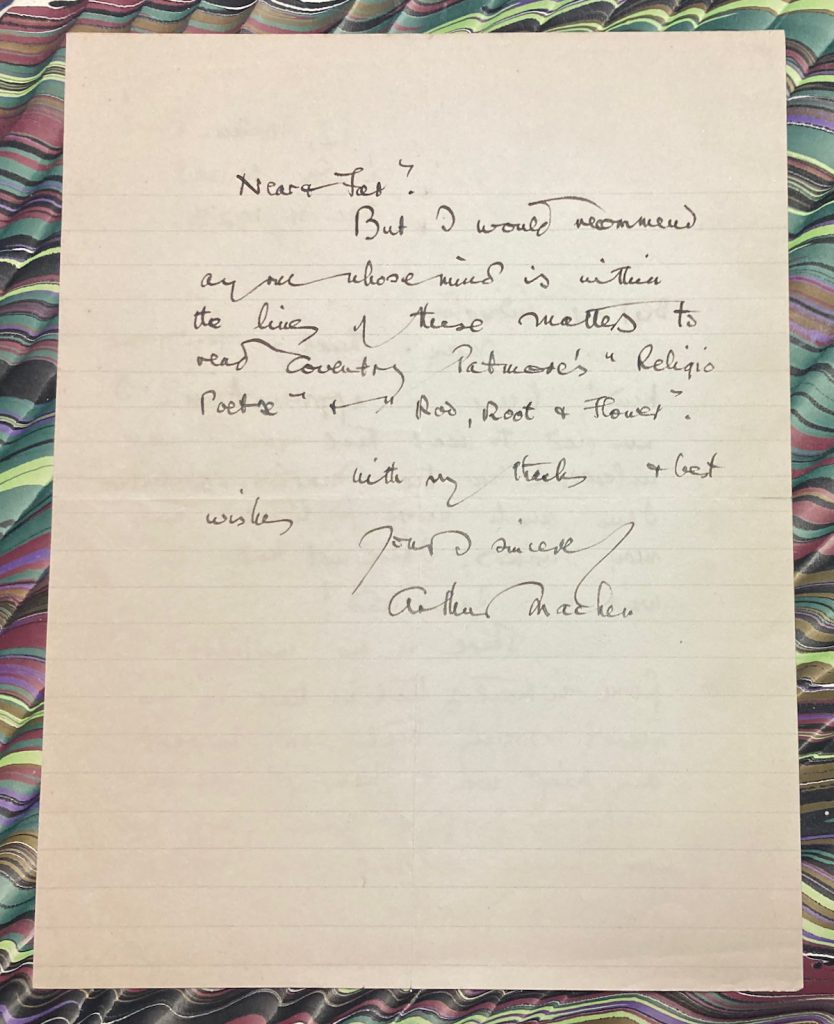

Transcribed in full:

12, Melina Place

London NW8

Dec. 11, 1923

Dear Mr Ludington

Many thanks for your kind letter of appreciation. I am glad to hear that you were interested in the Marks Exhibition. I am more fortunate than many writers. I have not had to wait until I am dead!

There is no initiation from without ; that is, there is no secret society that can impart anything worth hearing. The only initiation is from within, so that you have almost as much as I do, having read “Things Near & Far”.

But I would recommend to any one whose mind is within these lines to read Coventry Patmore’s “Religio Poetae” & “Rod, Root, & Flower”.

With my thanks & best wishes

Yours sincerely

Arthur Machen

“The only initiation is from within” is prime Machen, a generous and spontaneous response to a young worshipper. Ludington seems not to have attempted to continue the exchange and just this one glimpse remains from a century ago.

* Catalog of rare and choice books, first editions of modern authors, etc. Charles Dickens first editions including the renowned Lapham-Wallace copy of the Pickwick papers. Also the most important collection of first editions and original manuscripts of Arthur Machen ever offered. New York: Harry F. Marks, 1923. Goldstone & Sweetser 76b.

Not seen, but noted from the bibliographer’s copy held at HRC (Call no. Z 8230 H355 1923). The Machen items are nos. 202-248. [Images courtesy of HRC.]

** John Gawsworth. The Life of Arthur Machen. Edited by Roger Dobson. Friends of Arthur Machen / Reino de Redonda / Tartarus Press, 2005. Pp. 286, 300, 304.

The chapter endnotes record some of the prices in those far off days, including the manuscript of The Three Impostors at $775. By way of comparison, Marks Catalogue No. 4 (1919), presenting an abundance of curiosa, had listed a finely bound set of Casanova’s Memoirs, now for the first time translated into English (1894), at $250 without mention of Machen as the translator; a similarly bound set of the twelve volumes, with addition of the note [by Arthur Machen], appears in the 1923 catalogue at $200, where a fifteenth-century Flemish manuscript Book of Hours was priced $140. In 1925, Marks moved from lower Broadway to west 47th street and was the U.S. agent or distributor for the Black Sun Press.

Thanks to William Hutcheson who offered me the letter earlier this year.

N.B. This account picks up some threads from an earlier post, Peak Machen : 1923.

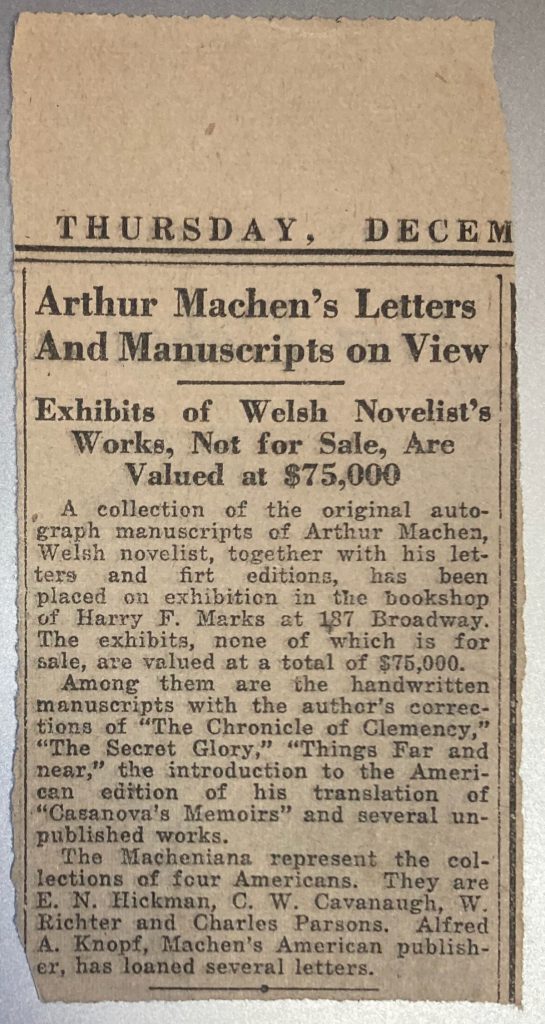

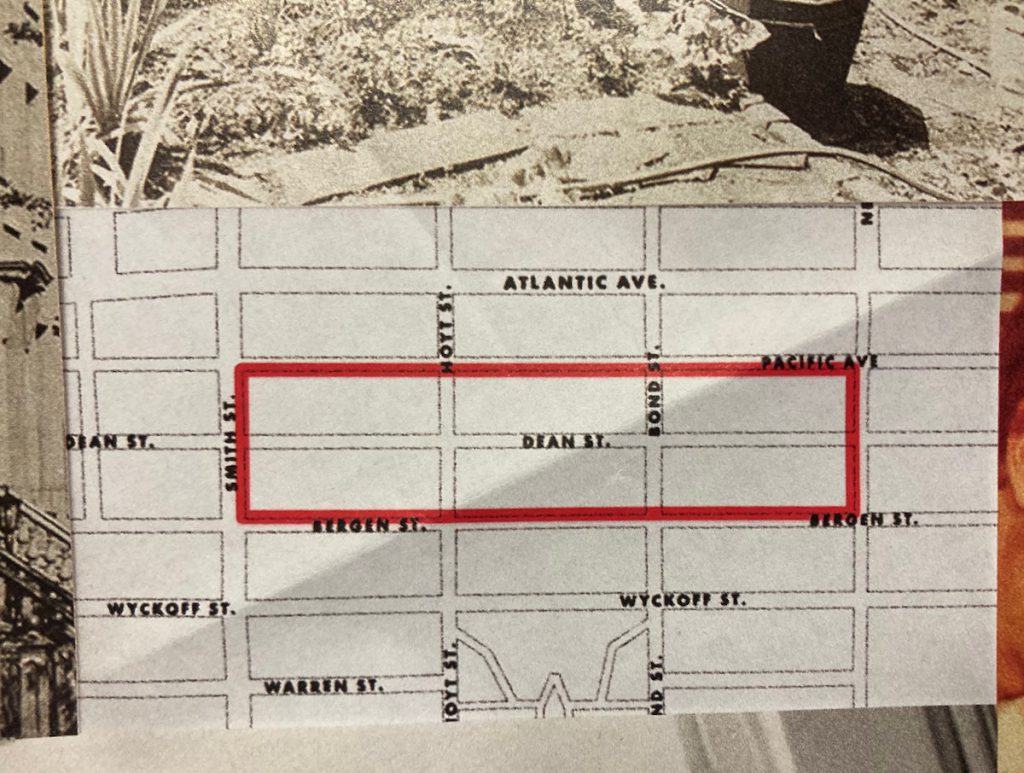

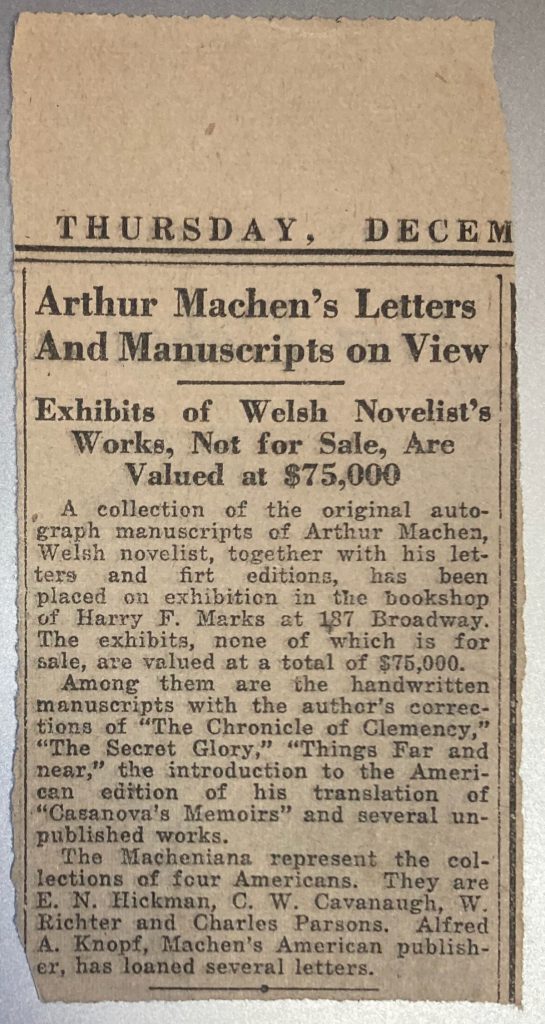

Addendum, 14 December: sometimes serendipity brings forth new information. Here is a clipping from the New York Tribune for a Thursday in December 1923 (likely 6 December):

This is a report of the exhibition at the Marks bookshop that prompted Mr. Ludington to write Machen. One can infer that Marks had sold most of the Machen manuscripts by this date. The Charles Parsons collection is now at Yale : it includes the manuscript of “The Garden of Avallanius”, known to us as The Hill of Dreams (Beinecke GEN MSS 256, Series I).