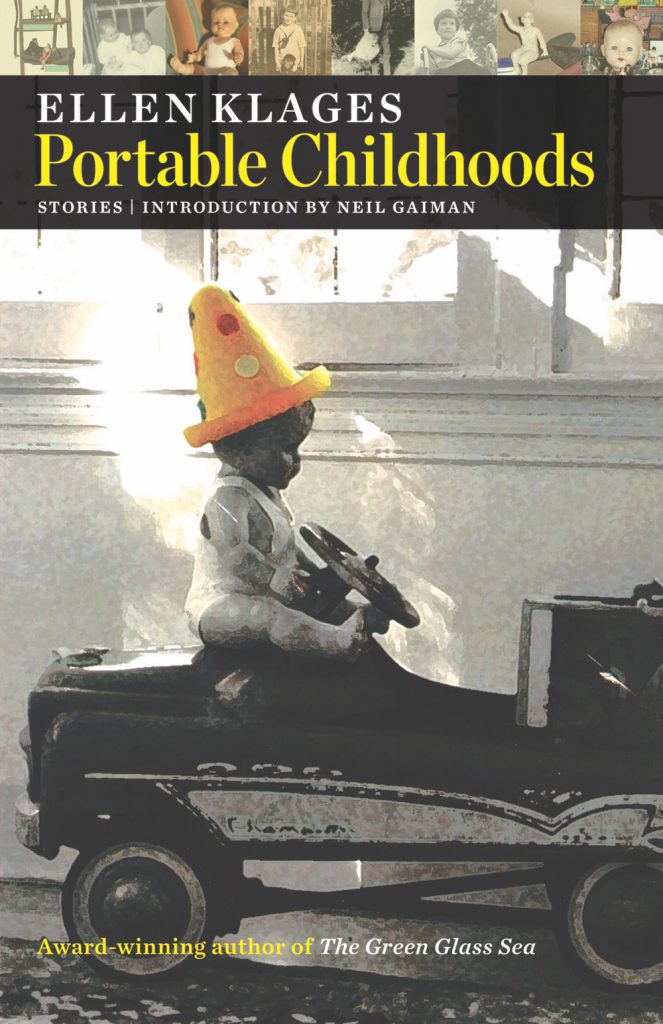

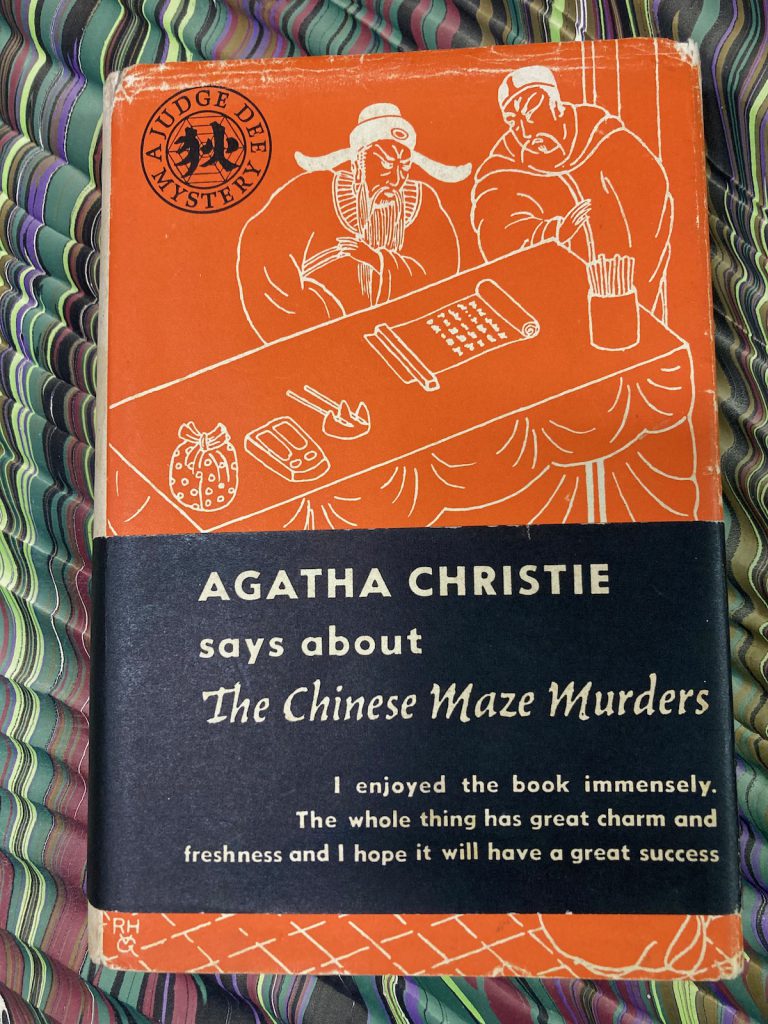

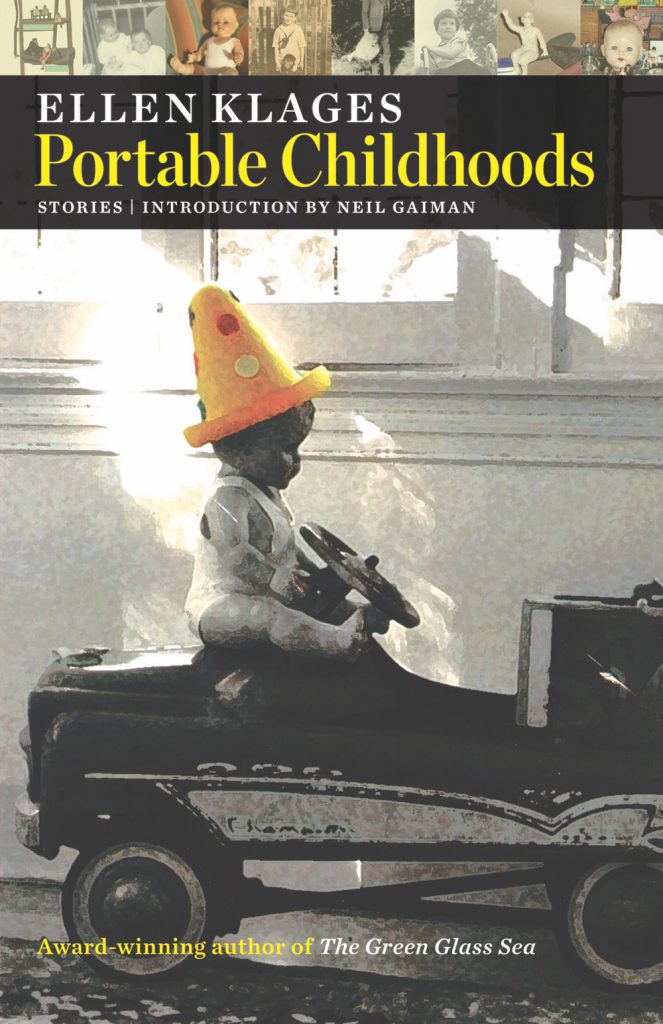

Portable Childhoods by Ellen Klages. [Introduction by Neil Gaiman]. San Francisco: Tachyon Publications, 2007. x, 210 pp. $14.95 (trade paperback)

reviewed by Henry Wessells

[Originally published in The New York Review of Science Fiction 19, no. 12, August 2007.]

Portable Childhoods arrived with a small note, Thought you’d enjoy Klages’ “In the House of the Seven Librarians”, and an illegible signature. I knew some of Ellen Klages’ work from the Infinite Matrix website and from F&SF; and Eileen Gunn once or twice told me funny stories of road trips they had made together. I was utterly unprepared for the energy and nimbleness of this collection of sixteen stories. Klages treads the invisible line between wonder and the mundane with total control, and her insights into the betweenness of childhood and the nature of becoming — becoming human, becoming adult — are fully earned and devoid of cuteness. After reading three or four stories, each with distinct characteristics (As one of her characters says, “It’s different every time.”), the range and subtlety of Klages’ prose made me think about how it is I look at short stories: to define just what are some of the yardsticks I use to recognize interesting work.

“In the House of the Seven Librarians” is a playful, feminist mirror to “The Library of Babel”: a tale of an almost wholly self-contained universe of books, but a library whose librarians have names, and who are competent to deal with eruptions of the unexpected into their routine, such as an infant girl returned in payment of overdue book fines. Klages’ story engages the idea of the library in America and the recent shift away from the book as central to the mission of the library. It’s also a great deal of fun, teasing us all with our fancies of what goes on after hours, or when the expected rules are changed: her list of “10 Things to Remember When You Live in a Library” is a recipe for mayhem and laughter, “Do not drop volumes of the Britannica off the stairs to hear the echo.” “In the House of the Seven Librarians” is also the story of a young person learning how and when to assert herself, to move from the familiar into the new.

The precise, rippling sentences of the ten vignettes of “Portable Childhoods” are the muscles of a neurosurgeon’s hands at work, not those of a boxer. Klages evokes the close focus of the child’s world at the same time as we learn of the longer perspective of the narrator, her mother. Each of the sections of “Portable Childhoods” contains the seeds of the others, and here as elsewhere Klages demonstrates an economy of words that brought Lydia Davis to mind. I am thinking of the careful observation of family life in “Our Kindness” from Almost No Memory (1997); Klages is a lavish maximalist by comparison, yet not one word is superfluous. No one who reads “Portable Childhoods” will thereafter view croutons and photons as unrelated.

The handful of short shorts in this collection proves Klages to be up to the demands of this perilous form. “Ringing Up Baby” (published last year in Nature) is snappy and worth of Fredric Brown in its closing ironies. From the famous passage in the writings of J. S. Haldane about an “inordinate fondness” for bugs, “Intelligent Design” goes after root causes rather than secondary effects, thereby surpassing even Le Guin’s “She Unnames Them” (1985): “Creeping things covered every surface, legs and claws and pincers scuttling and skittering.” Postmodern pulp is deftly skewered even as its essence is savored in “Möbius, Stripped of a Muse”.

Klages reminds us that childhood is an unsettled time, and that children are often bereft of power to respond to what the adults around them are doing. The opening story of the collection, “Basement Magic”, takes place in suburban Detroit. Klages describes the stepmother in terms one will not encounter in Snow White. “Kitty, the new Mrs. Ted Whittaker, is a former Miss Bloomfield Hills, a vain divorcée with a towering mass of blond curls in a shade note her own. In the wild, her kind is inclined to eat their young.” Mary Louise is a quiet child, unable to defend herself against Kitty until she makes friend with Ruby, a transplanted conjure woman from the deep South. There is a flavor of Avram Davidson’s “Where Do You Live, Queen Esther?” in the dynamic of Ruby and her employer, but I was surprised at how carefully Klages kept Mary Louise in the center of the story, and the magic that unfolds is ultimately hers. The transformation Mary Louise makes is analogous to that of the unloved child in the Paul Bowles story “Kitty” in Midnight Mass (1981). I must assume the name of the stepmother is chosen with deliberate irony, for Klages works an identical effect in “Flying over Water”.

”The Green Glass Sea” is a haunting account of a picnic at the original ground zero in 1945. Klages allows her narrator to describe events whose portent the reader comprehends far more clearly than the young girl who is experiencing them. There is no condescension or denial of dignity, only (only!) the evocation of loss and the space in which our harrowing present begins to unfold its true shape.

“Time Gypsy” is a tale of time-travel, love, and reinventing of the history of science. Carol McCullough is sent back in time by Chambers, the head of the physics department, a Nobel laureate whom she suspects of having designs on the fourth, unpublished paper of Sara Clarke, a brilliant scientist who died untimely. McCullough finds herself ill-prepared for the intolerance of 1950s California and meets an unexpected ally in Clarke. History unfolds according to the known record, but McCullough has planted evidence of the false pretenses by which Chambers published the work that won him the Nobel prize. “Time Gypsy” is the longest story in the collection, but Klages writes just as deftly at this length as in her shorter pieces. The overt critique of the male hierarchies of science in the 1950s is inseparable from the love affair and the time-travel aspects of the story; I am reminded of the Cambridge scientist Rosalind Franklin, whose contribution to unlocking the structure of DNA was largely overshadowed by her colleagues Crick and Watson.

In the course of reading and thinking about Portable Childhoods, I found myself questioning the nature of my comparative processes. It is not about yardsticks to measure a given length, nor about fixed landmarks that I am seeking as I move through the forest of story. Both notions are much too inert to describe the experience of coming upon familiar signs from a fairly broad universe of stories that I draw upon to orient myself.* It is not that seeing X means Y must be near. Absolutely not, for Klages is not a derivative writer: these stories convey her own voice and sure pace. It is much more that the stories of certain authors serve me as a descriptive language, as an allusive choreography: when reading something new, I recall similar incidents and images and effects in the dance of story.

So when I say that “A Taste of Summer” makes me think of Robert Sheckley, it is not entirely the same Sheckley I think of when I read Rudy Rucker. In this story, Klages works her best science magic: an episode of childhood — a walk to the crossroads ice-cream parlor — is rigorously observed in its fabric of small resentments and the way these suddenly fall away.

Mattie considered her options and decided that a walk with a popsicle at the other end was probably the best of them. [. . .] It was definitely going to rain, and she didn’t think it was going to wait until dinnertime. She though for a minute about going back, but decided that maybe being wet on a sort-of adventure was better than being dry and bored for sure.

And then Klages works a twist of events that opens possibilities to Mattie and to the reader. Crossing the yellow lines on the road, and seeking shelter from a sudden storm in the ice-cream shop, Mattie meets Nan Bingham, who gives her a scoop of a new flavor: apple pie à la mode ice cream. There is electricity in the air, and they seek refuge in the storm cellar — Mattie herself making the comparison to The Wizard of Oz. Nan tells about her hobby, “painting with flavors”, and is suitably inarticulate. Nan gives Mattie a bit of pure flavor, an experiment. “She tasted a fuzzy sweetness, then coconut and a salty tang then a different, sharper sweet and a bit of burnt and smoke and way in the back of her mind she thought about her father mowing the grass.” Klages then empowers Mattie to put the unspoken into words: “this was more like a movie that went from my tongue to my brain.” It is these descriptions of the flavor chemist’s hobby that invoke Sheckley for me: in Crompton Divided (1978), Sheckley plays with smells that elicit landscapes and memories. But where Psychosmells, Inc. is a corporation that sells a commodity to rich, elderly men for whom its use is a demonstration of power, in “A Taste of Summer”, the wealth of sensation that Nan Bingham creates is a secret gift to a child, “like toffee made on another planet. [. . .] It’s different every time.”

Portable Childhoods is a complex and rewarding book. Tachyon and publisher Jacob Weisman are to be commended for publishing it. Ellen Klages is indisputably a writer whose work arose within the science fiction mode; yet even as science fiction is part of the weave of her stories, she turns the garment of genre inside out to remind us that her universe (and ours) is wider than literary commonplaces.

Henry Wessells lives and read in Montclair, New Jersey. His latest whimsy is the Endless Bookshelf, simply messing about in books: endlessbookshelf.net.

* The review as written included a short list, omitted in the published version and repurposed for the ’shelf as Yardsticks ; or how to compare Apples & Oranges.

Copyright © 2007 by Henry Wessells. All rights reserved.