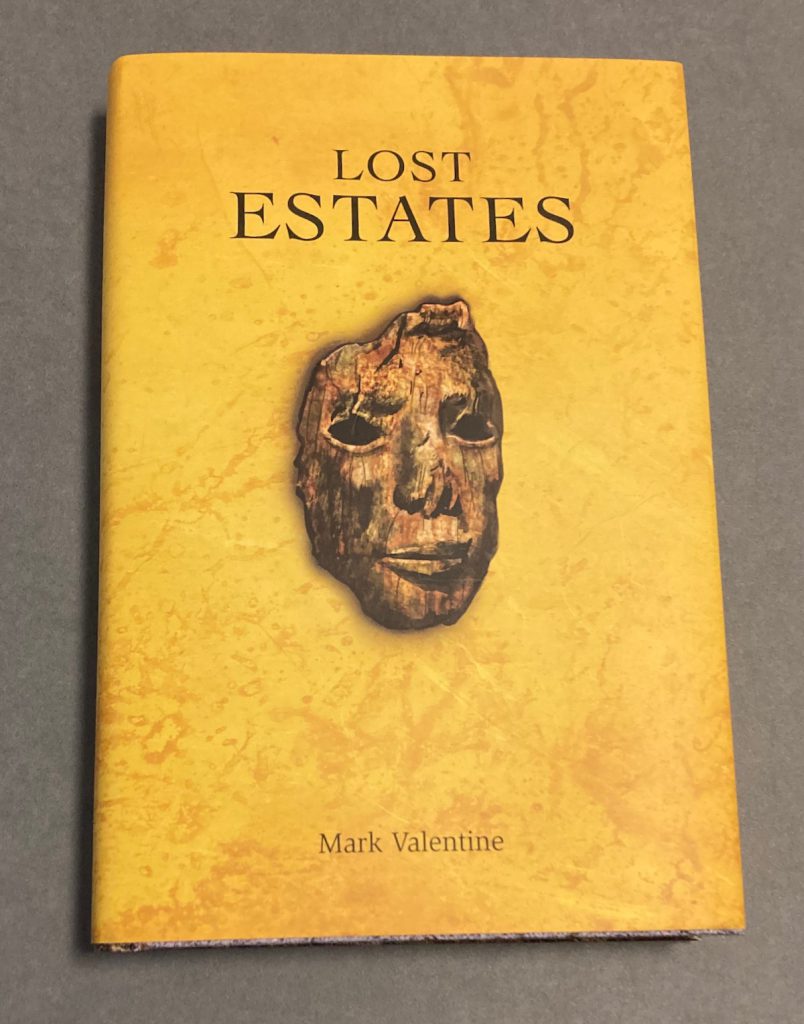

— Mark Valentine. Lost Estates. Swan River Press, 2024. [From the author].

Collection of a dozen stories, four unpublished, including the excellent title story

— — —

— John O’Donoghue. The Servants and other strange stories. Tartarus Press, [2024]. Edition of 300.

Collection of nine stories and novellas ; including “The Irish Short Story That Never Ends” : though its title reveals how it must end, this is pitch perfect and evocative and finely executed. Michael Swanwick —himself a master of concise, brilliant short stories — notes, “John O’Donoghue knocks it out of the park . . . I’m Irish, so this goes to the heart of a lifetime of reading for me.”

— — —

— John Buchan. The Three Hostages. Houghton Mifflin, 1924.

Re-read this for the first time in more than forty years, for an essay appearing in Wormwoodiana on the centenary (1 August).

— — —

— Anthony Powell. A Question of Upbringing (1951) ; A Buyer’s Market (1952) ; The Acceptance World (1955) ; At Lady Molly’s (1957) ; Casanova’s Chinese Restaurant (1960) ; The Kindly Ones (1962) ; The Valley of Bones (1964) ; The Soldier’s Art (1966) ; The Military Philosophers (1968) ; Books Do Furnish a Room (1971) ; Temporary Kings (1973) ; Hearing Secret Harmonies (1975).

I have been working at the ‘Dance to the Music of Time’ over the past several months, mostly reading the dozen novels out of sequence, which seems a reasonable enough approach, since the narratives flit and somersault across time and the parade of characters is intermittent and recurring by design. The humor is dry and Powell’s principal strategy, “the discipline of infinite obliquity”, will not be to every reader’s taste, but things do happen, often as sudden surprises punctuating a circumspect, even evasive, chronicle. And of course the sentences and paragraphs sometimes turn in midstream to undermine or contradict the initial idea or perspective expressed. Or how about this : “She had the gift of making silence as vindictive as speech.”

Powell’s cycle was described by several of his contemporaries as an English Proust but that now seems to me to be a reductive statement : there is attention to art, music, and aesthetics, and a complex, intertwined cast of artists, hacks, critics, businessmen, elegant and not-so-elegant family members, and even Venice makes an appearance, but Nicholas Jenkins is, by temperament, energy, and accomplishment, about as far from the “Marcel” narrator as can be and so is the overall tone. I like The Military Philosophers (which does have a direct nod to Proust) and At Lady Molly’s most of all, but this is maybe saying “poached” or “over easy”. Certainly the outcomes of Hearing Secret Harmonies are a long way from the schoolboy memories of 1921 in the first volume.

— — —

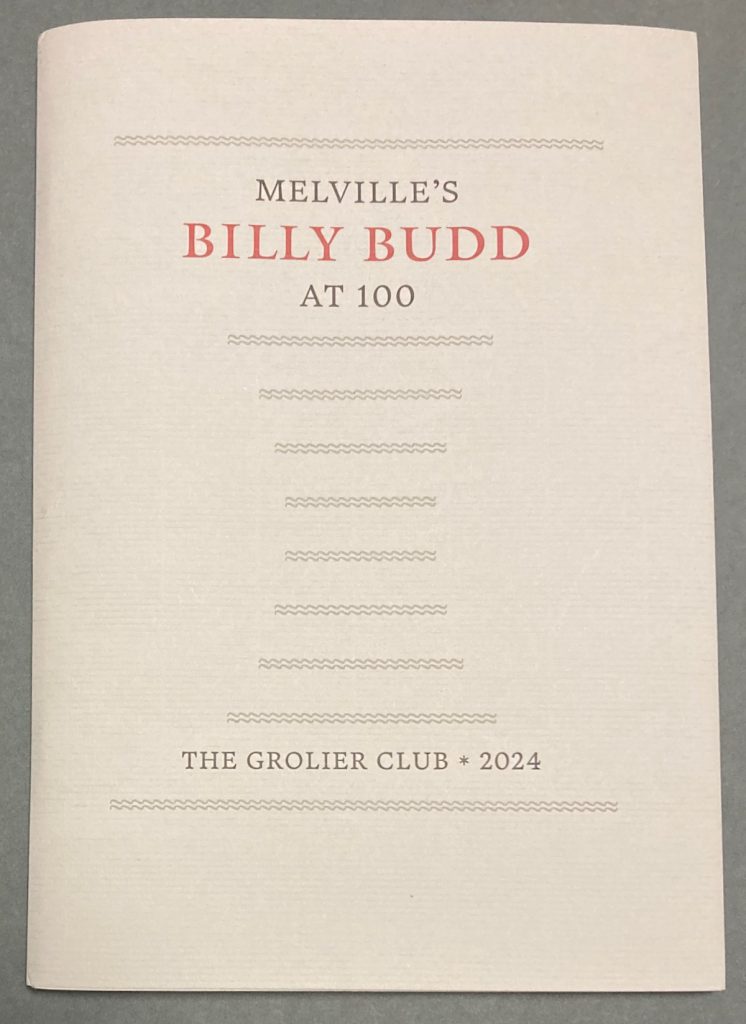

— (MELVILLE, HERMAN). Melville’s Billy Budd at 100. A Centennial Exhibition at the Grolier Club and Oberlin College Libraries. Introduction and Descriptions by William Palmer Johnston. Frontispiece portrait of Melville by Barry Moser, color plates. The Grolier Club, 2024. Edition of 375 copies printed by Bradley Hutchinson in Austin, Texas. [Gift of the author].

Advance copy of this concise, elegant catalogue for the show (12 September to 9 November in NYC) : 49 entries, 1843-2024, including some legendary Melville rarities and new work by an American master. A symposium on Billy Budd will be held at the Club on 9 October in connection with the exhibition.

The catalogue is distributed by the University of Chicago Press.

— (MELVILLE, HERMAN) Bound to Vary. A Guild of Book Workers exhibition of unique fine bindings on the Married Mettle Press limited edition of Billy Budd, Sailor. New York: Guild of Book Workers, 1988.

A superb copy of this edition of Billy Budd (one of the unique bindings) will be on view at the Grolier.

/ file under : chronicle of an obsession

— — —

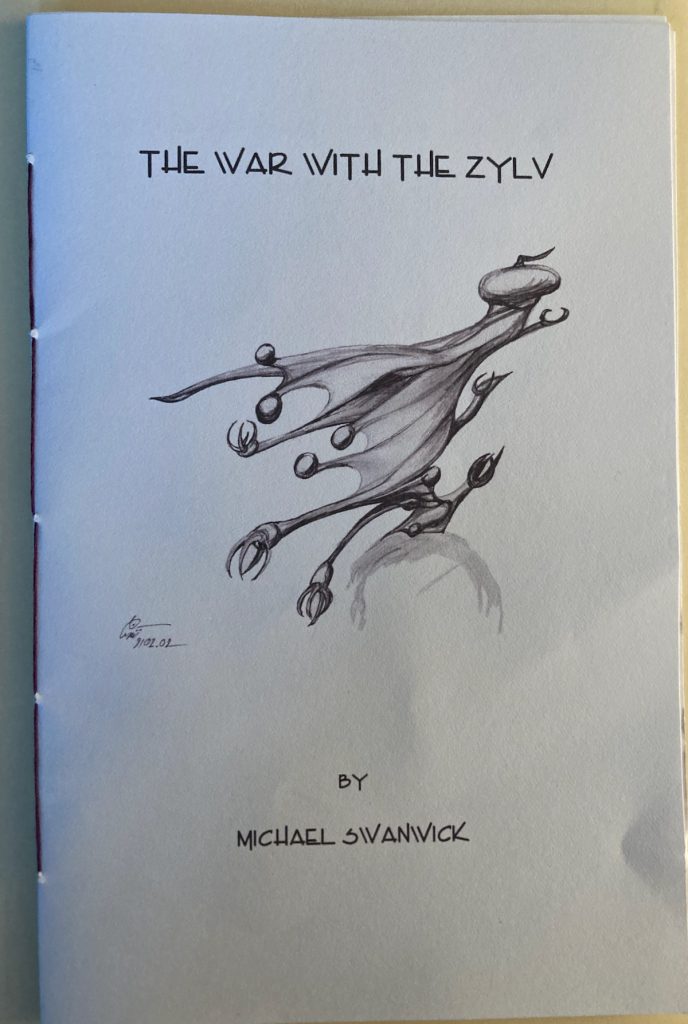

— Michael Swanwick. The War with the Zylv. Cover illustration by Ariel Cinii. Dragonstairs Press, 2024. Edition of 100.

— — —

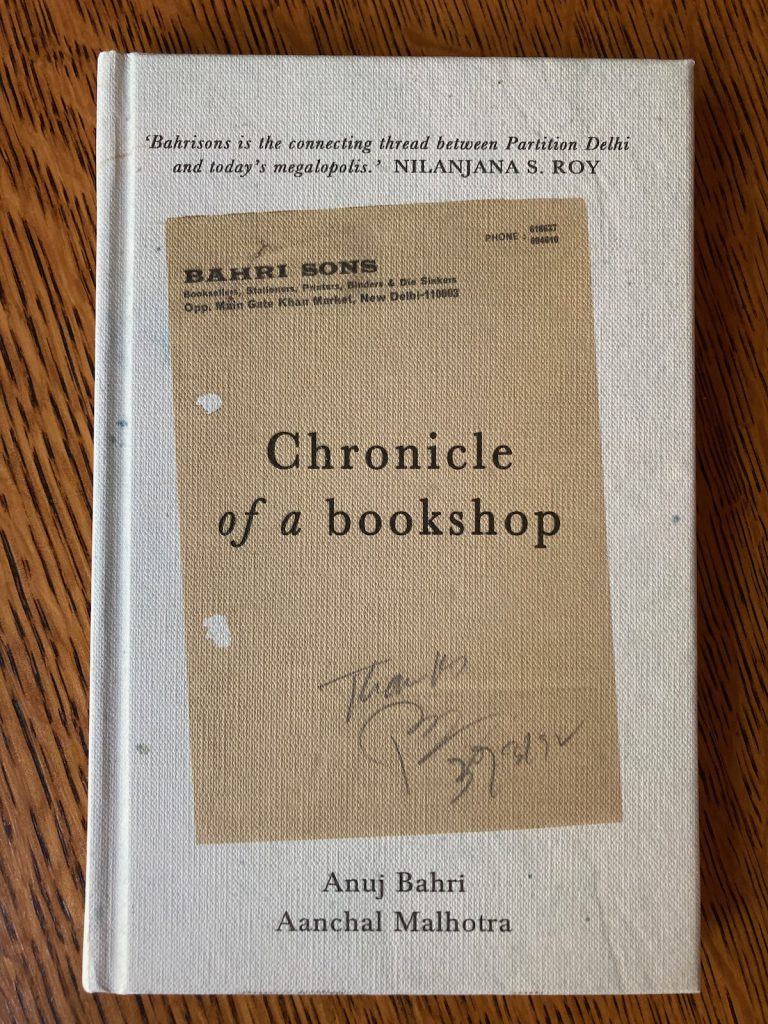

— Anuj Bahri and Aanchal Malhotra. Bahrisons. Chronicle of a Bookshop. [New Delhi :] Tara India Research Press, [2024].

Seventieth anniversary memoir and keepsake from this New Delhi bookshop established by an enterprising young refugee couple displaced during Partition : ‘we were not just in the business of selling books, but rather, building relationships’.

— — —

— Bob Rosenthal. Fifth Avenue Overhead. Edge Books, [May, 2024].

“Stories of Poetic Survival” by the author of Cleaning Up New York. This is a fun book!

— Arthur Machen. A Reader of Curious Books. [Edited by Christopher Tompkins]. Darkly Bright Press, [2024].

Expanded second edition (originally issued in 2020) of this annotated compendium of early work by Machen, reviews and literary miscellanies from the pages of Walford’s Antiquarian in 1887 [cf. Goldstone & Sweetser, pp. 141-3], some using the pseudonym Leolinus, and often containing in miniature some of the author’s later interests and motifs.

— John Masefield. Sard Harker. Heinemann, 1924.

For a forthcoming essay.

— Matthew Needle, Bookscout. An Appreciation by His Friends. Cambridge, Mass.: Charles Wood, Bookseller, 2012.

Reminiscences by Gregory Gibson, Adrian Harrington, Robert Rubin, Marcus McCorison, Roger Stoddard, Charles Wood, Stephen Weissman.

— — —

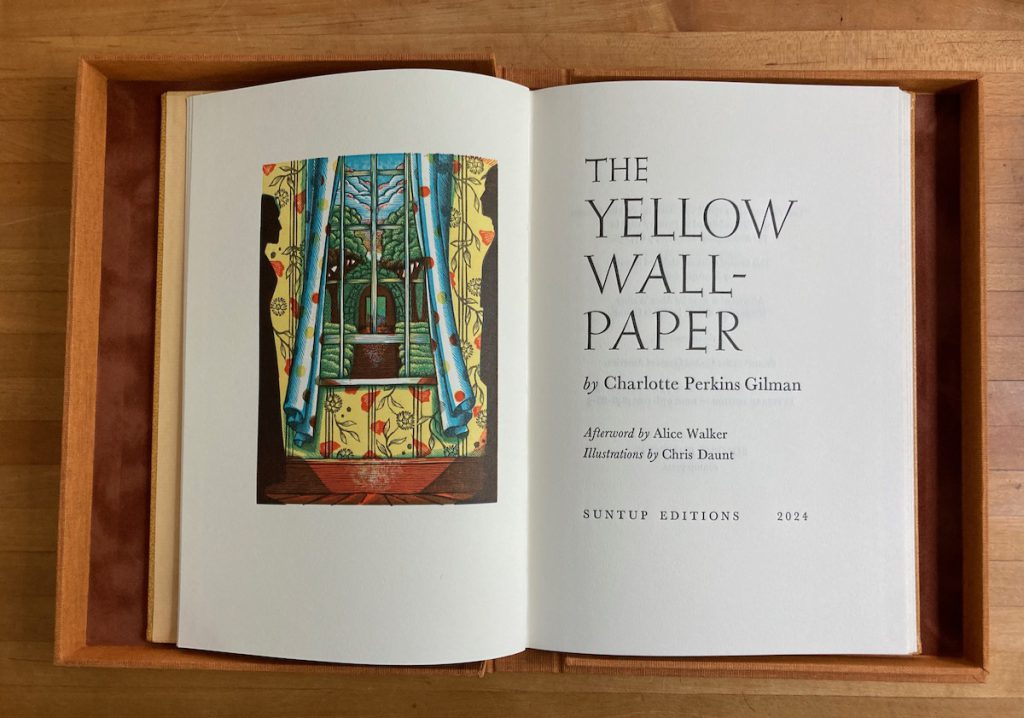

— Charlotte Perkins Gilman. The Yellow Wall-Paper. Afterword by Alice Walker. Illustrations by Chris Daunt. Suntup Editions, 2024. Edition of 376 copies, signed by Walker and Daunt.

— — —

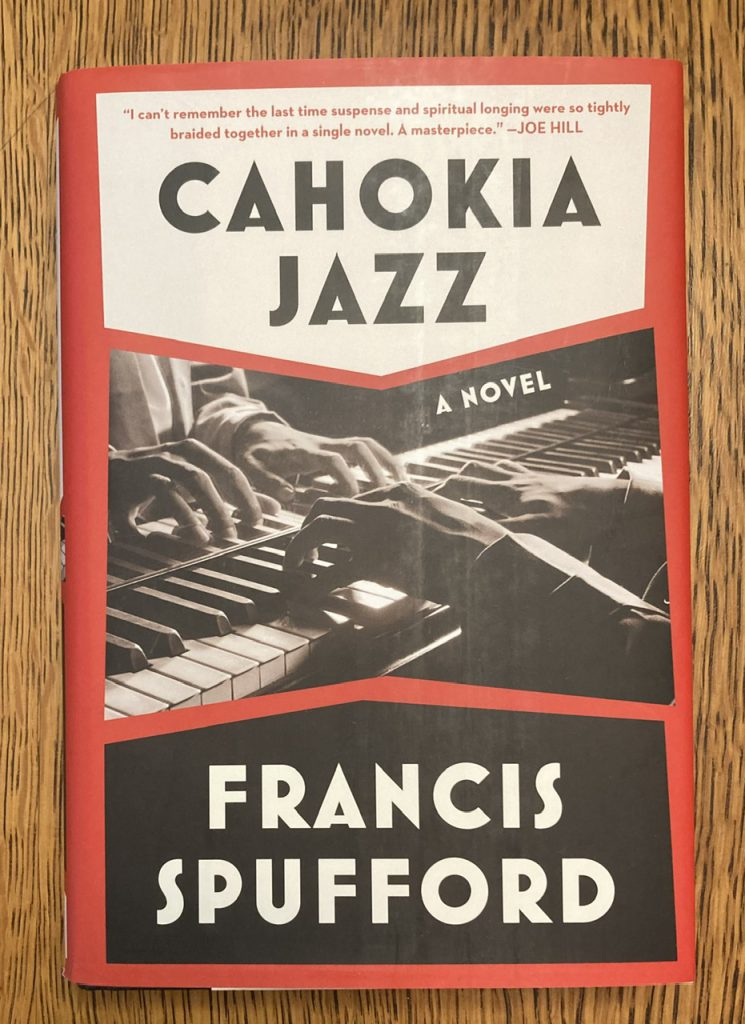

— Francis Spufford. Cahokia Jazz [2023]. Scribners, [2024].

A Prohibition novel, a jazz novel, and an excellent novel of an alternate America, a narrative organically rooted in language and anthropology. I really liked this one.