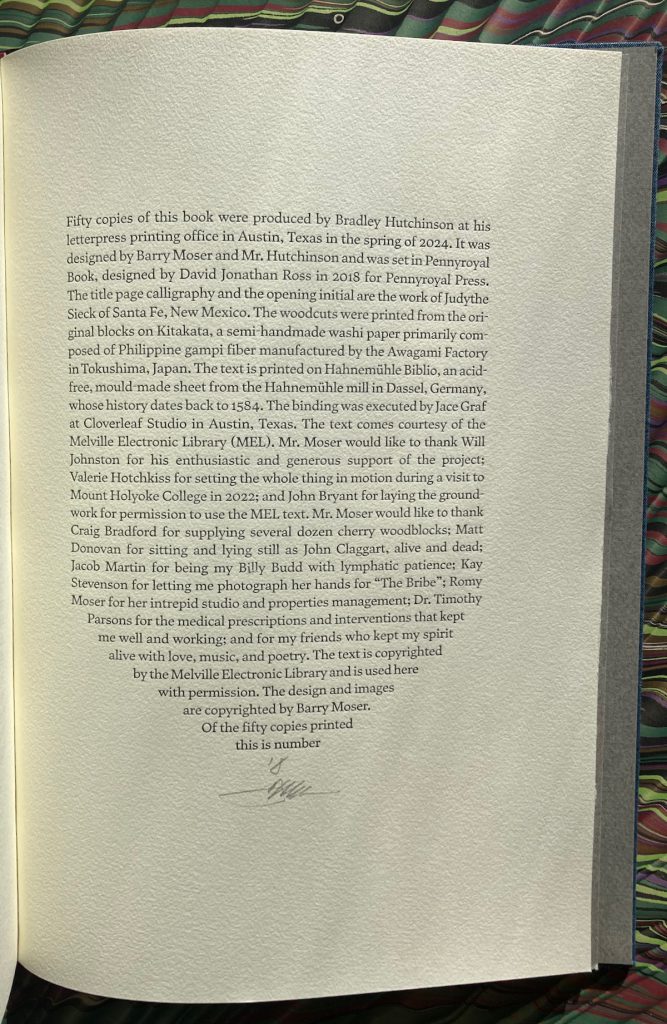

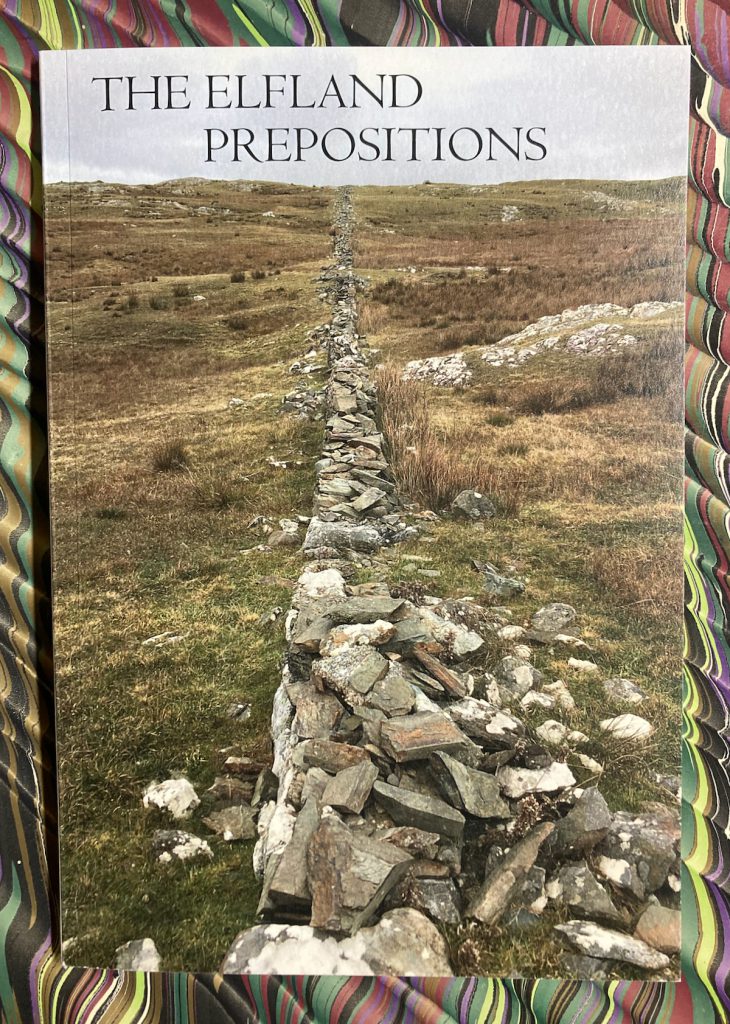

The Elfland Prepositions, published 27 February

advance presentation copies, at the post office ready for mailing [26 February]

—

in production

— Henry Wessells. The Elfland Prepositions. Temporary Culture, 2025.

Printed on Mohawk superfine white eggshell. Pictorial wrappers. 26 copies, lettered A to Z, were reserved for presentation ; there were also 100 copies numbered 1 to 100.

Proof copy above (received 12 February 2025) ; proofs corrected & in production (14 February 2025), published 27 February 2025.

Copies now offered for sale, click on link or photo to order.

ISBN13 978-0-9764660-0-0 ISBN 0-9764660-0-1

Collection of four previously unpublished short stories.

Elfland is not a nice place, but it’s important to know how it works.

— — —

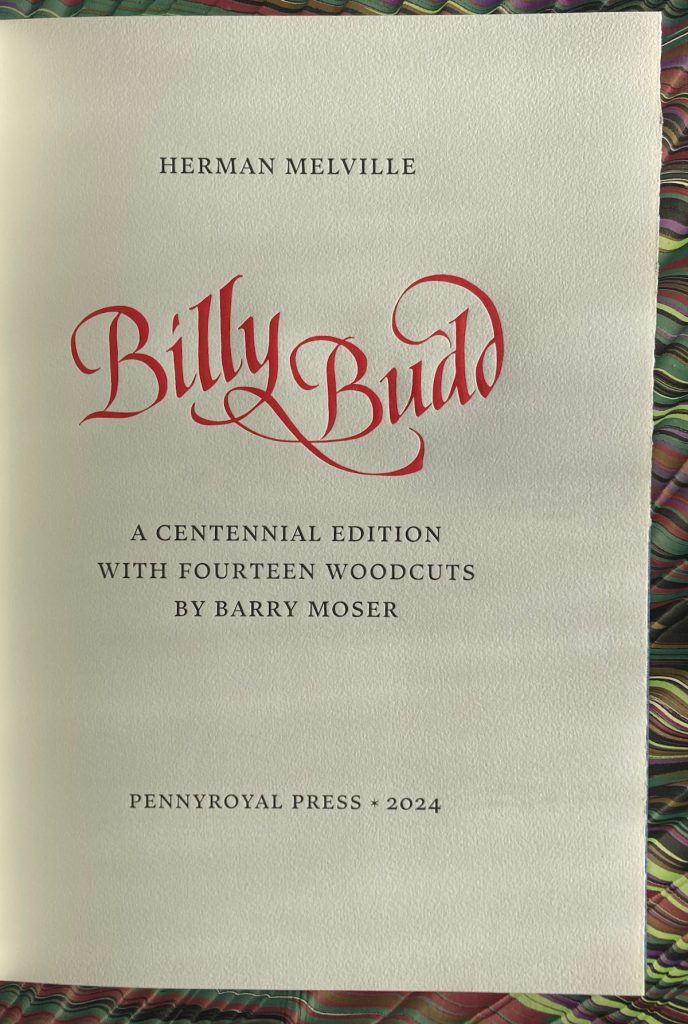

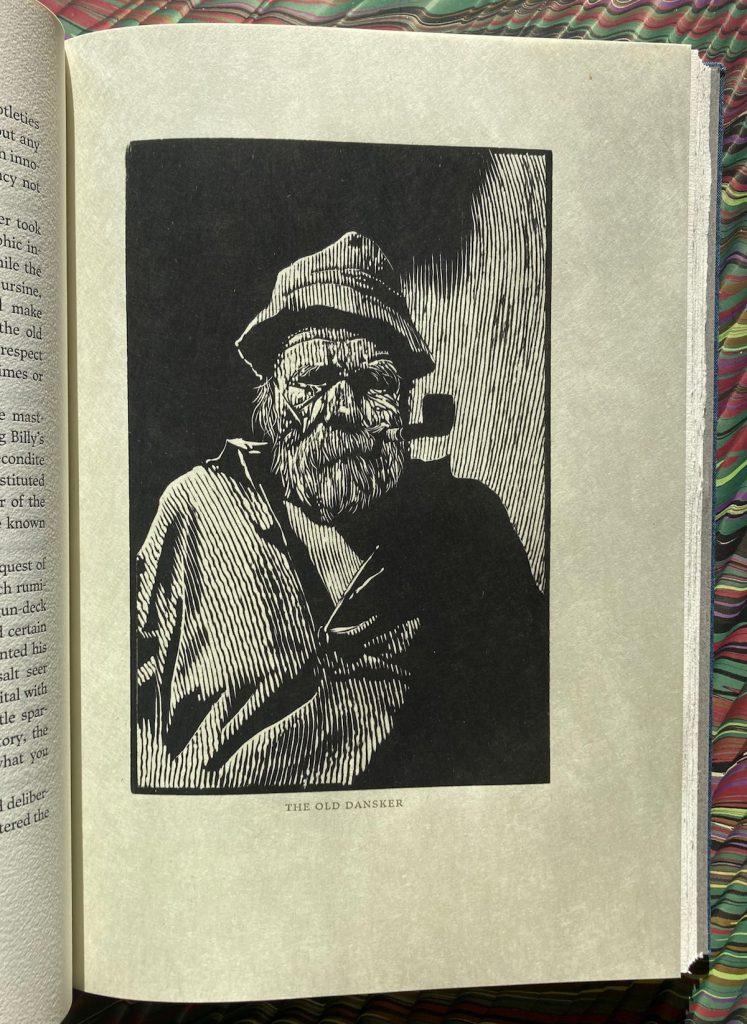

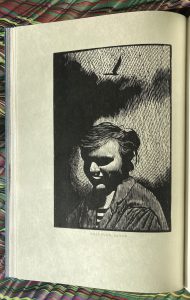

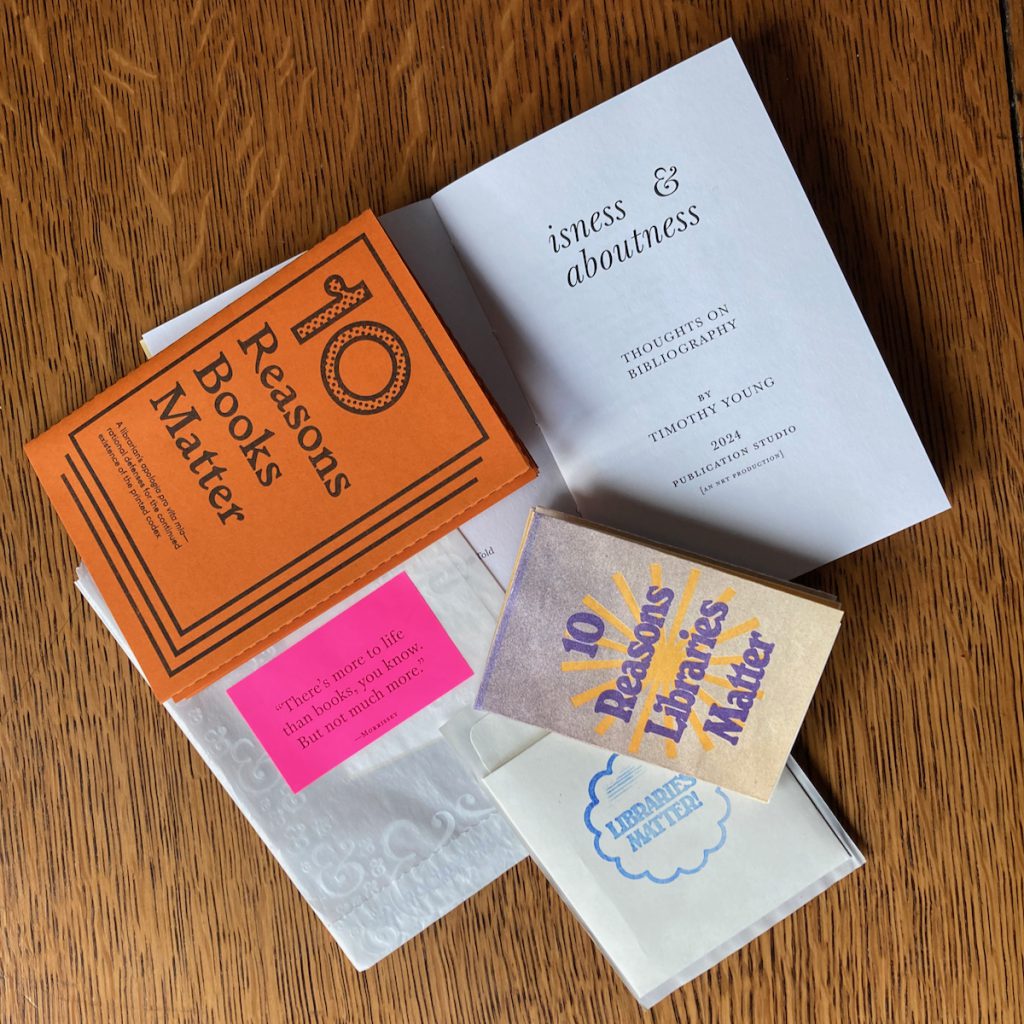

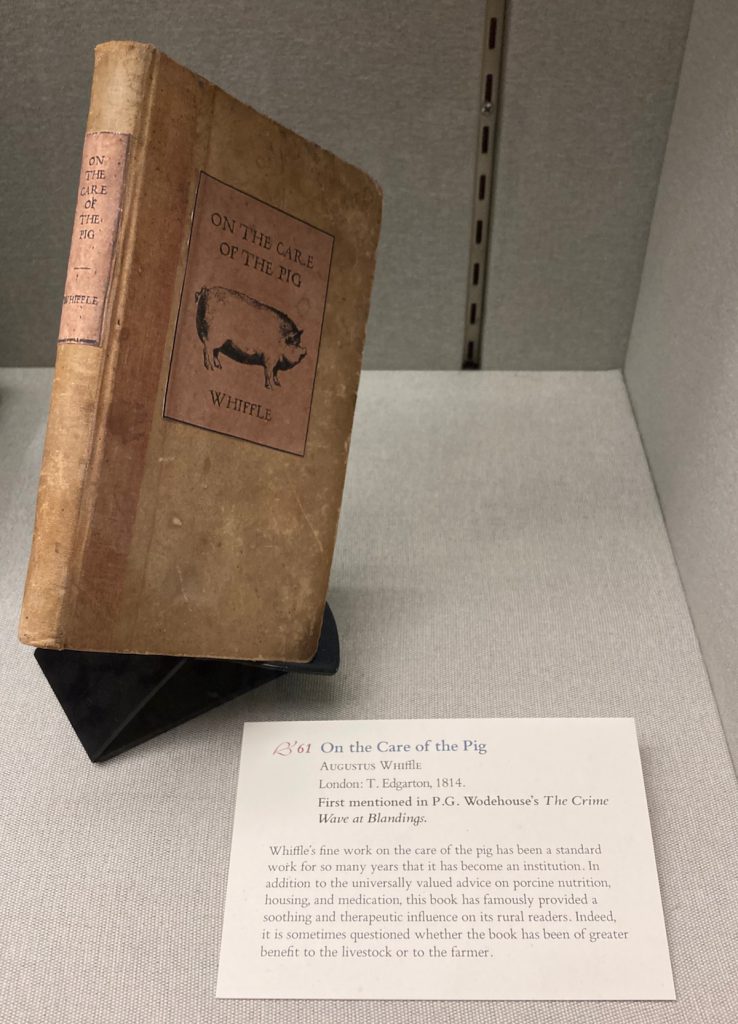

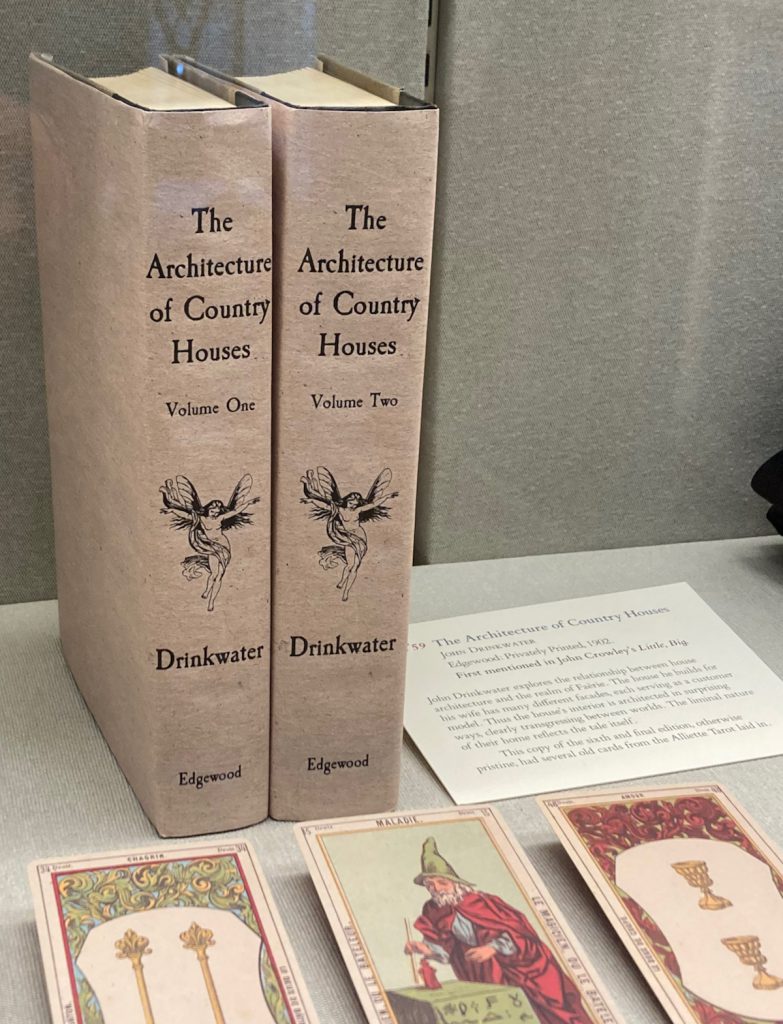

seen in the imagination, and at the Grolier Club :

two entries from the recent Grolier Club exhibition, Imaginary Books. Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works Found Only in Other Books, from the collection of Reid Byers.

— — —

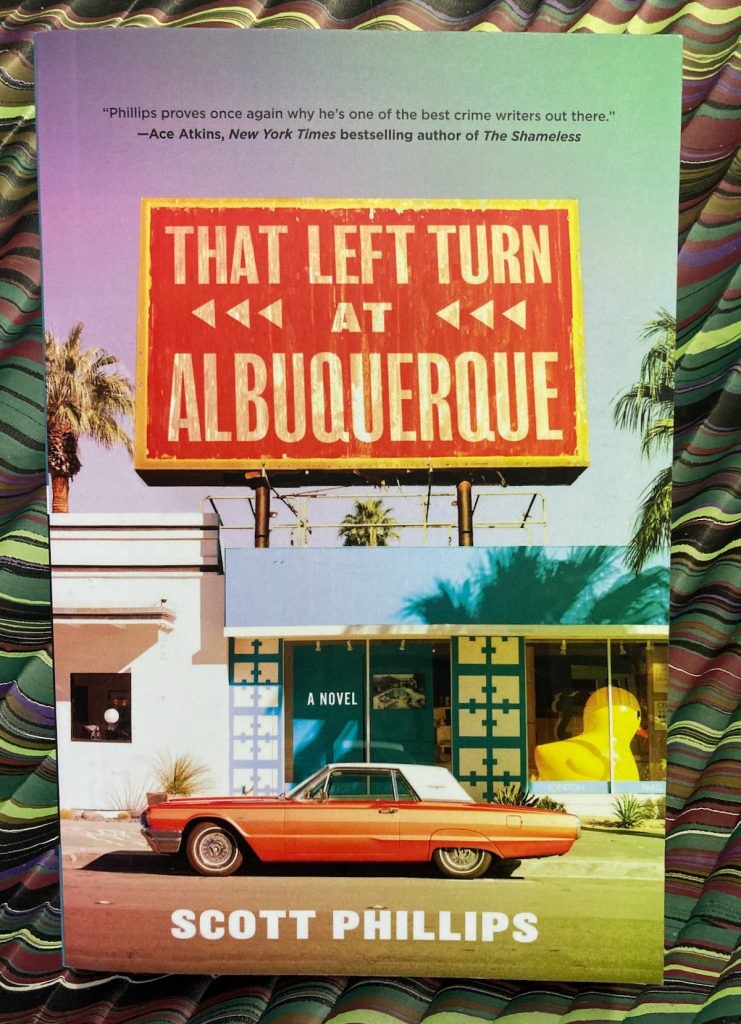

current reading

— Charles Robert Maturin. Melmoth the Wanderer: A Tale [1820]. With introduction and notes by Victor Sage. Penguin Books, [2000].

/ into the labyrinth, again

— — —

recent reading

— Len Deighton. Hope. HarperCollins, [1995].

— — Charity. HarperCollins, [1996].

— — Winter. A Novel of a Berlin Family. Knopf, 1987.

Germany in the world, 1899-1945 ; back story or bedrock for the Bernard Samson novels.

— — —

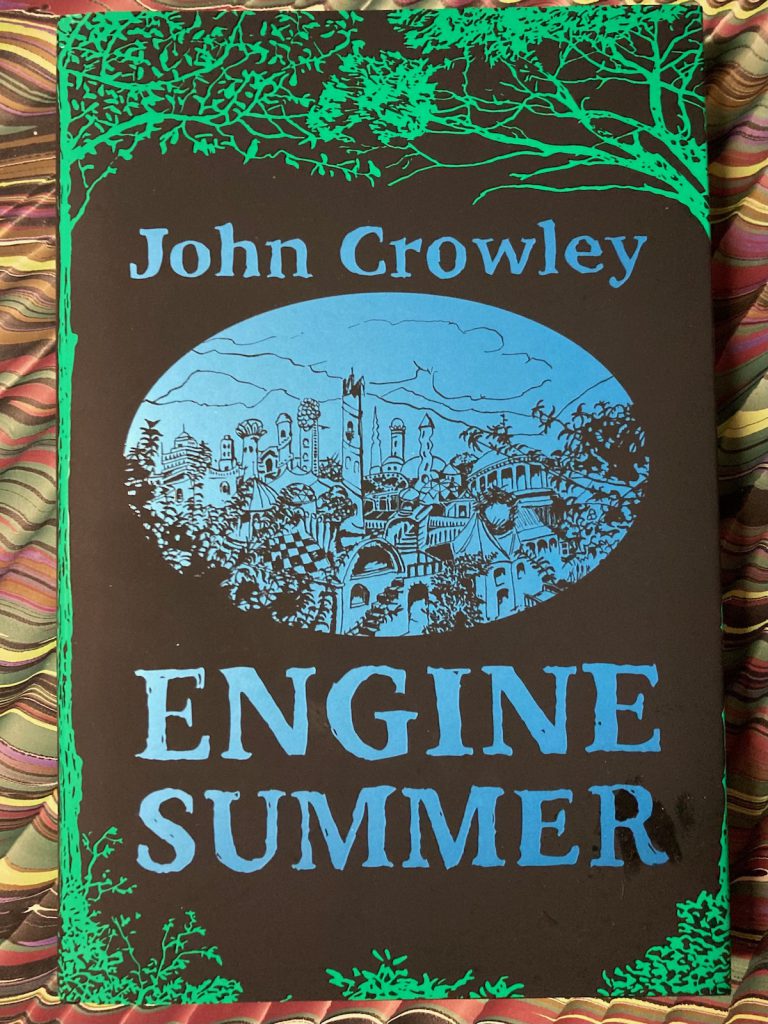

‘away from the clank of the world’

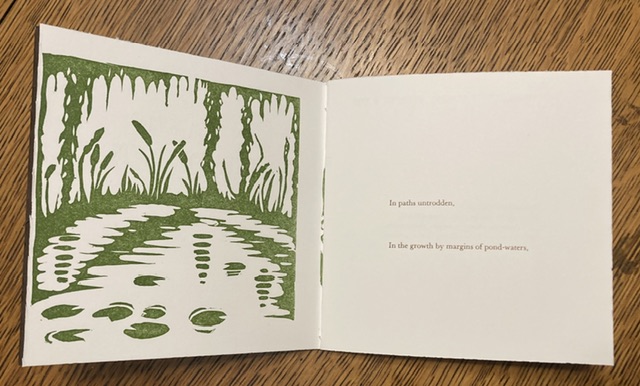

— Walt Whitman. In Paths Untrodden. Printed in brown ink, blockprint illustrations in green and blue. [16] pp. [The Letterpress at Oberlin, January 2025]. Edition of 217.

Calamus 1, from the 1860 Leaves of Grass, with blue herons and green marsh plants. [Gift of VH].

— — —

Hard Rain by Janwillem van de Wetering

A short note now up (in English) on the excellent and informative Dutch site

https://janwillemvandewetering.nl/favoriete-boek/

— — —

“not relics of the past, but pockets of the future arriving ahead of schedule”

— Christopher Brown, over at The Clearing (the blog of Little Toller Books)

— — —

“When I look at that obscure but gorgeous prose-composition, the Urn-burial, I seem to myself to look into a deep abyss, at the bottom of which are hid pearls and rich treasure ; or it is like a stately labyrinth of doubt and withering speculation, and I would invoke the spirit of the author to lead me through it.”

— Charles Lamb on Sir Thomas Browne, quoted by Hazlitt, in “Of Persons One Would Wish to Have Seen” (1826)

— — —