recent reading :

— 100 Years 100 Voices. The Chapin Library. [Edited by Anne Peale.] Williams College, [2025].

A beautiful and richly illustrated celebratory catalogue, presenting selected items from the Chapin Library at Williams College, established with gifts from Alfred C. Chapin in 1923. Chapin had been buying very good and interesting books from the best dealers for nearly a decade before the initial gift, and the collection has grown since, through purchase and donation. The Chapin Library had a dynamic founding librarian, Lucy Eugenia Osborne, and has always functioned as a teaching library for undergraduate instruction. This intention shines through in this anthology. The collection ranges from European incunables and an Eliot Indian Bible (1663) to an Audubon Birds of America purchased from James Drake, from a miniature printing press owned by John Fast to a recent risograph artist book (and four copies of the 1855 Leaves of Grass). The short pieces about the books are by alumni (long gone and recent), past and present curators and librarians, faculty members, and others. The photographs, by Nicole Neenan, are nicely reproduced. This is an important publication, a concise and compelling testimony about why books and libraries are central to education.

— — —

— Timothy d’Arch Smith. The Stammering Librarian. [Strange Attractor, 2024]

I am delighted to have come across this collection of essays by bookseller, novelist, and bibliographer Timothy d’Arch Smith, whose novel Alembic (1992) appears in my Grolier Club exhibition checklist. The title essay and one or two of the other pieces link up directly to the concerns of his excellent memoir of bookselling in London in the 1960s, The Times Deceas’d (2003). There are memoirs of persons real and imaginary, including The Rev. T. Hartington Quince M.A., a Nicholas Jenkins / Anthony Powell pastiche now first published for a wider audience, though the British Library entry for the original appearance (in an edition of 15 copies in 1991, shelfmark YA.1992.b.6526), records Nicholas Jenkins as a “creator” ! Cricket, novelist Julia Frankau, school slang, and Aleister Crowley are other topics.

— — —

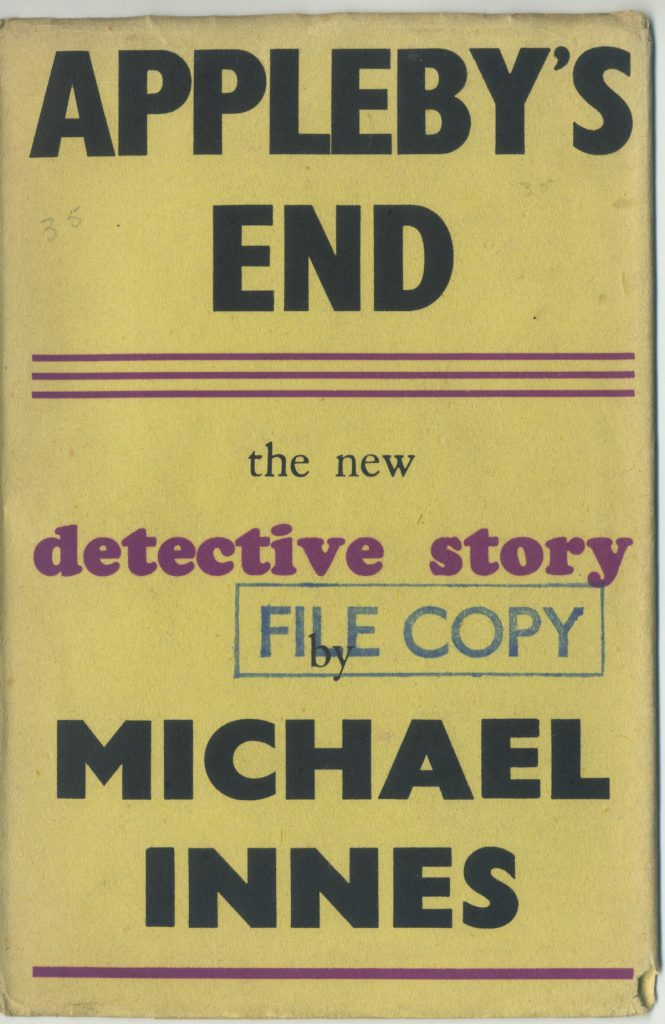

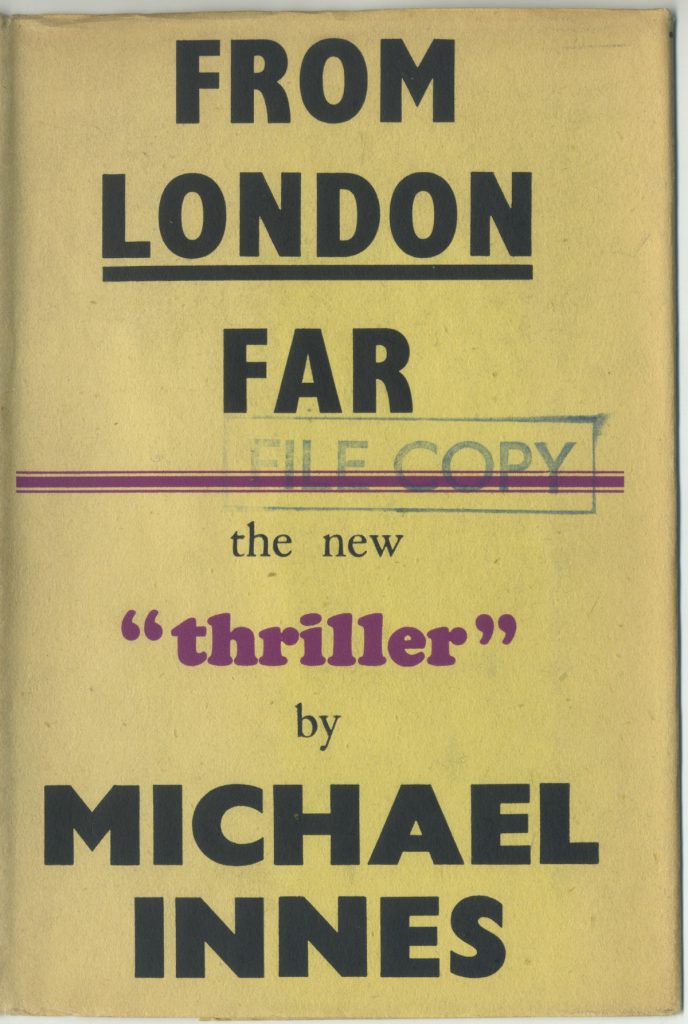

Over the next several weeks it will become ever clearer that I have embarked upon reading Michael Innes, whose wordplay and inventiveness are a pleasure. John Clute alerted me to The Secret Vanguard, and Mark Valentine lists Appleby’s End among his short list of Finest Quality Old English Yarns. I am enjoying the variety of this box of mostly tatty paperbacks — after reading a POD edition of The Secret Vanguard I decided that I am happier with a worn paperback — and I will eventually do something than merely extract interesting phrases.

— Michael Innes. Stop Press [1939]. Penguin Books, [1958].

——The Gay Phoenix. A Novel [1976]. Book Club Associates, [1976].

——. Hare sitting up [1959]. Penguin Books, [1964].

Jean turned and faced him. ‘Could you possibly,’ she said, ‘cut the cackle? And tell me what all this is about?’

——. Appleby’s End [1945]. Penguin Books, [1972].

Abbott’s Yatter, King’s Yatter, Drool, Linger Junction, Sleeps Hill, Boxer’s Bottom, Sneak, Snarl, Appleby’s End, Dream

‘Mister,’ he said heavily, ‘did ’ee ever see a saw ?’

— — —

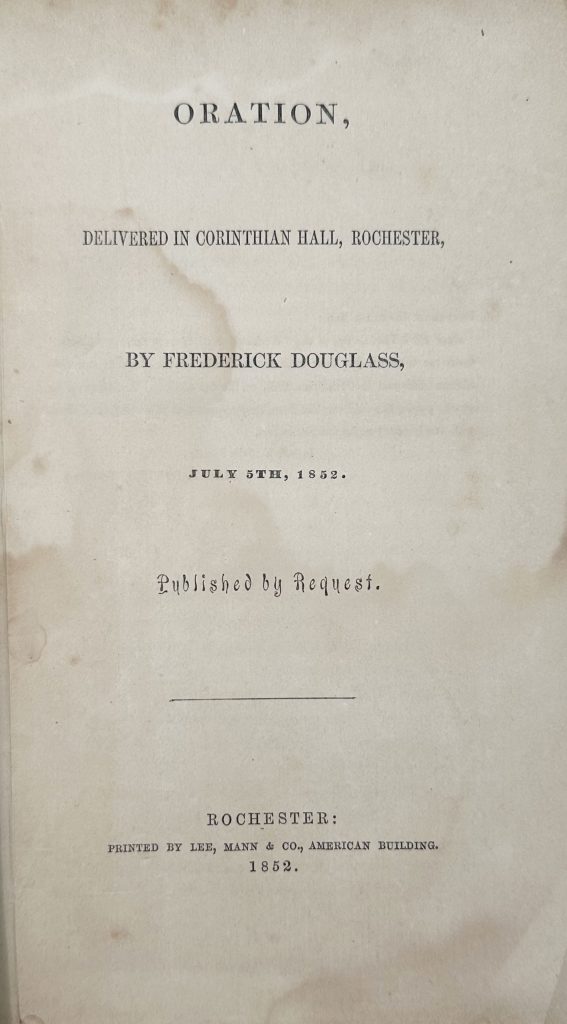

— Michael Zinman. The Critical Mess. [Privately printed], 2025.

Compendium of articles by and about legendary collector of Americana Michael Zinman, whose “critical mess” theory is trickier than a casual glance might suggest :

“If you have enough stuff, good and not so good, you see things that someone collecting only fine copies will miss. This doesn’t in any way cast aspersion on the collector who desires the finest copy of a work, it’s just another way of approaching this world.”

— — —

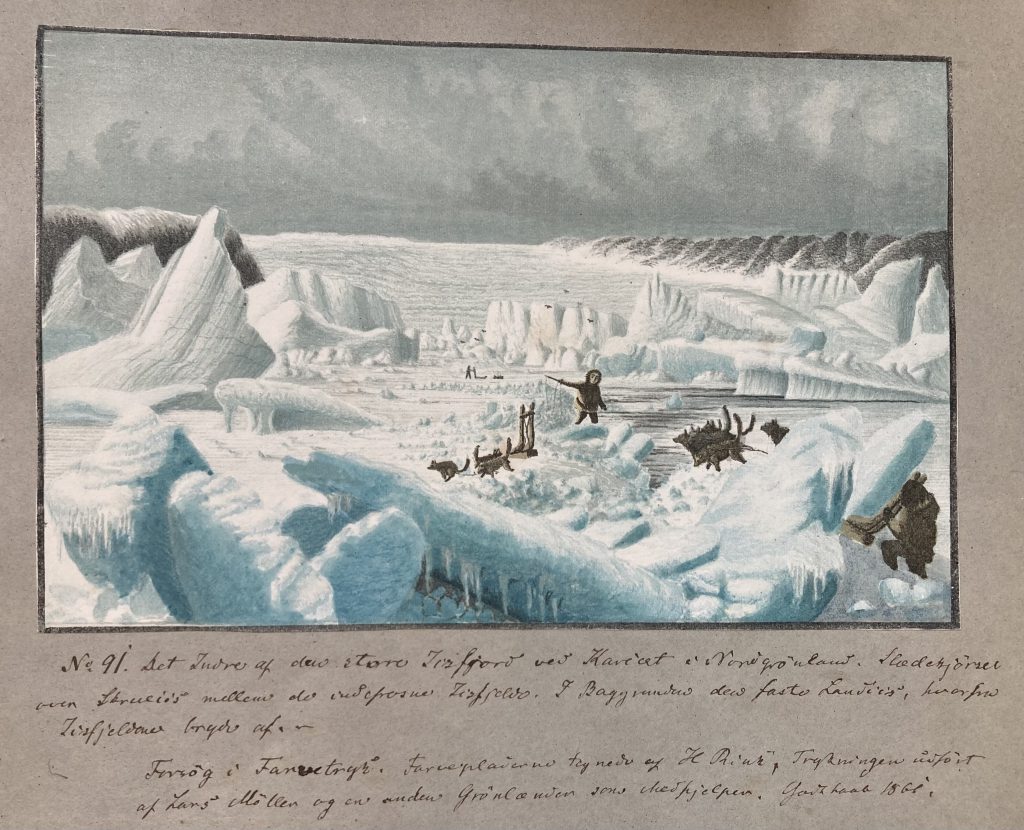

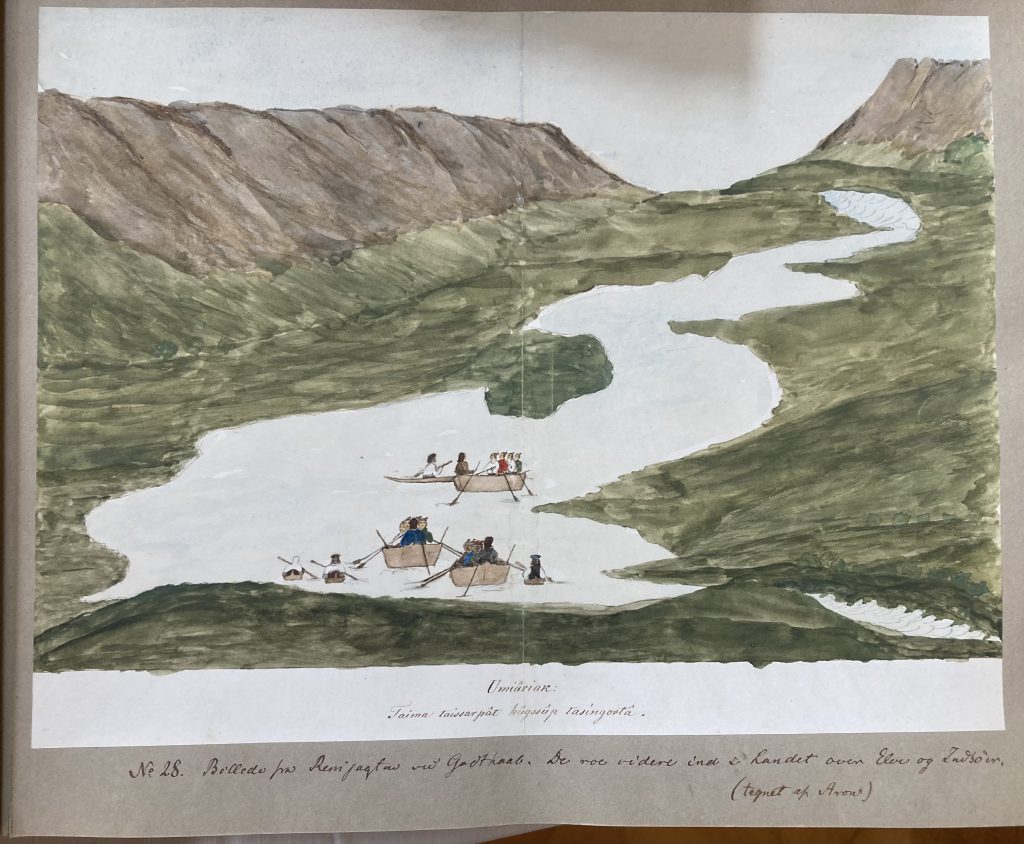

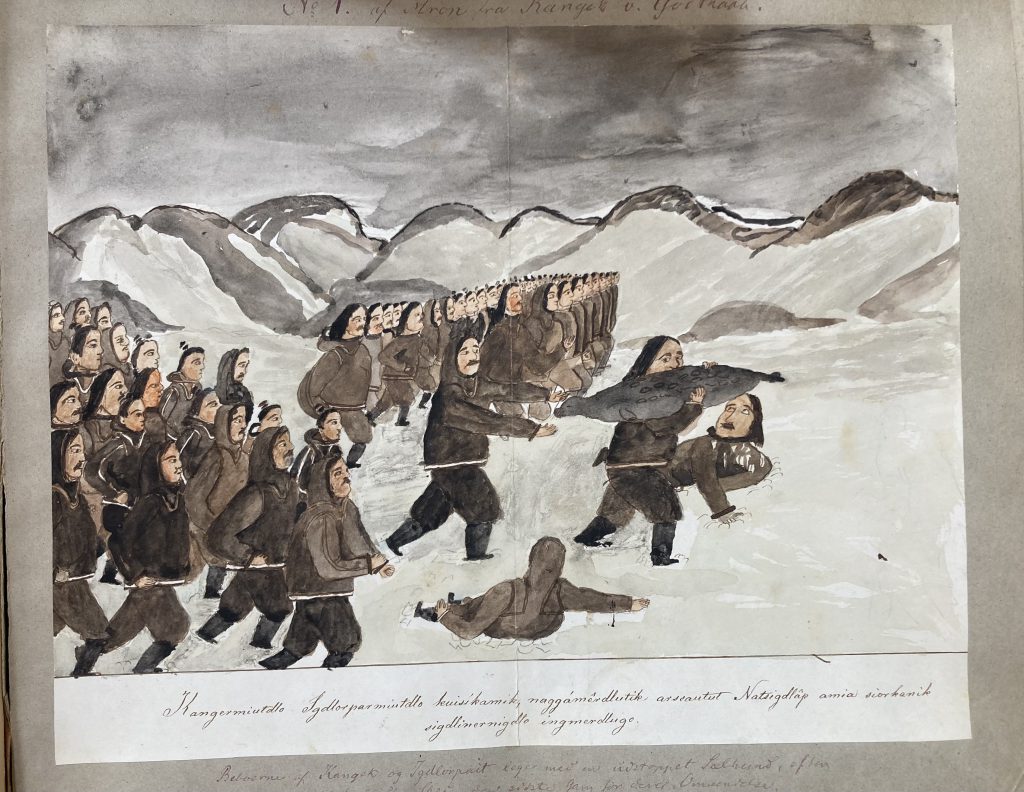

![Arne Jacobsen and Flemming Lassen. The House of the Future. [Copenhagen, 1929]. Drawing at the Royal Library in the Skatte / Treasures exhibition](https://endlessbookshelf.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/IMG_2267-1024x984.jpeg)