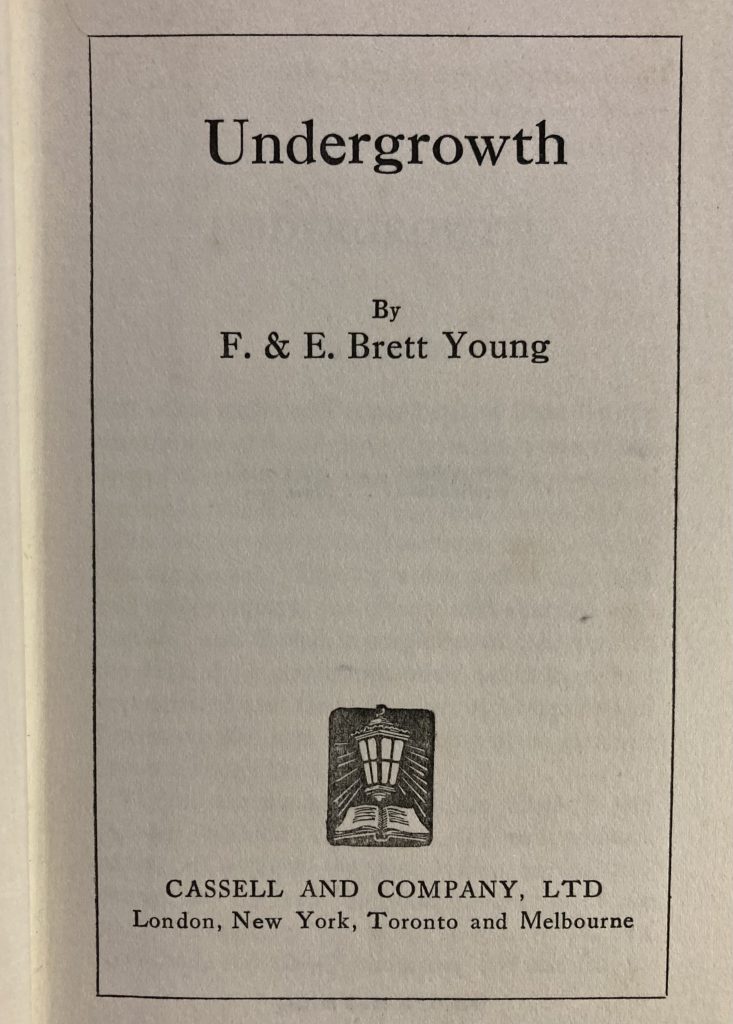

— F. & E. Brett Young. Undergrowth [1913]. Cassell, [Popular Edition, 1925].

Undergrowth is a brisk, interesting novel of the subjective experience of the uncanny in a remote landscape. It is the first book by doctor and novelist Francis Brett Young (1884-1954), written with his brother Eric and published just before the first world war. The influences are plain to see: Algernon Blackwood and, explicitly, Arthur Machen. Undergrowth is formally a club story and begins with a frame setting as mundane and chummy as the opening of a John Buchan yarn (I’ll circle back to those three names on occasion), when the unnamed narrator walks through stinking, “devitalized” Soho streets to the Étoile gleaming amber through the fog. The table talk turns to “pagan” landscapes in England and “cheap literary revivals” dismissed by the narrator, but his companion proposes a remote mountain valley where, despite sunshine and a jolly little brook, he “left in a deuce of a hurry” after an uncomfortable half an hour.

Undergrowth is the story of Forsyth, a construction engineer who comes to rural Wales to supervise the completion of a dam and reservoir which will flood the sparsely populated Dulas valley. The manager is a cockney named Hayward. Forsyth’s lodgings are in the house of an unlettered Welsh shepherd, Abel Morgan, who functions as the Celtic other and stands as a mirror of the moods of Forsyth and Hayward. Forsyth has an uneasy dream his first night in the house:

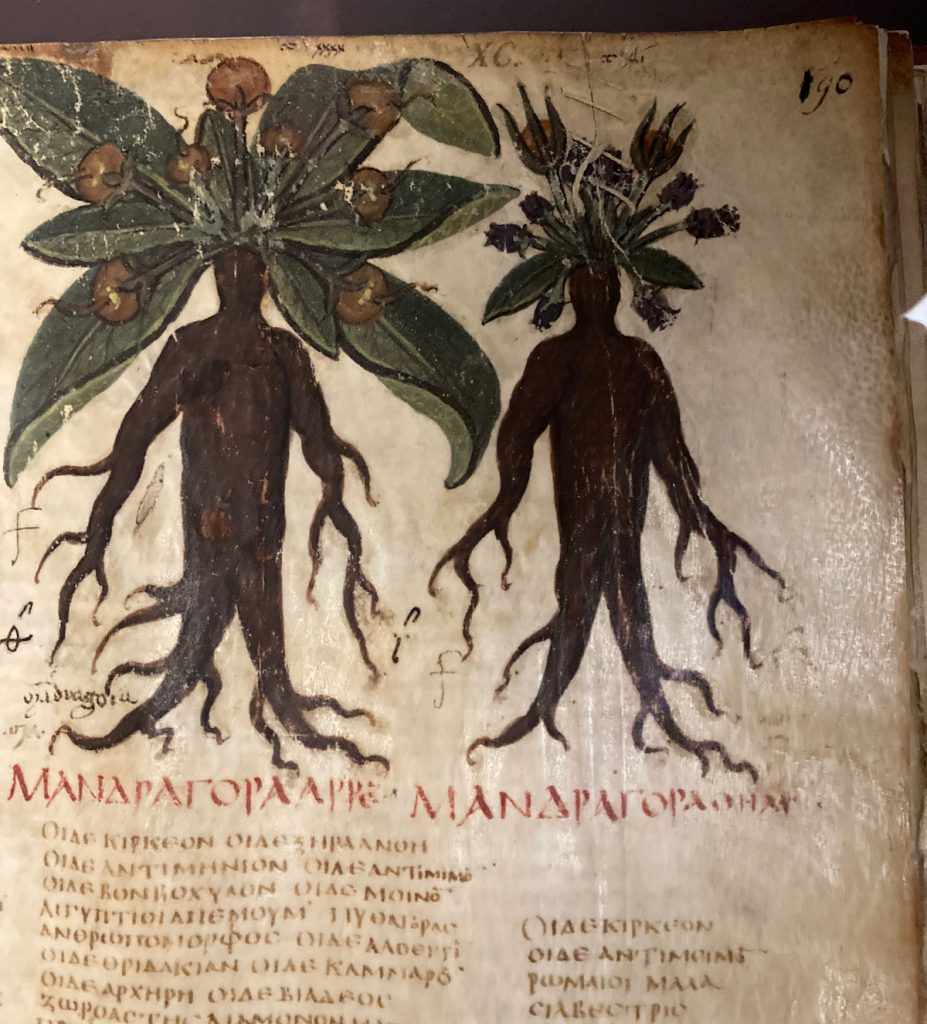

It seemed to him that he was stifled with the green which surrounded the house; that the trees of the woods which climbed the mountain above, and the tangled thickets that tumbled to the river, were robbing him of his breath. On every side green multitudes hemmed him in — gnarled monsters with twisted arms for branches, sappy climbing things, relentless parasites, like snakes. He could not breathe for the oppression of this hostile vegetable life.

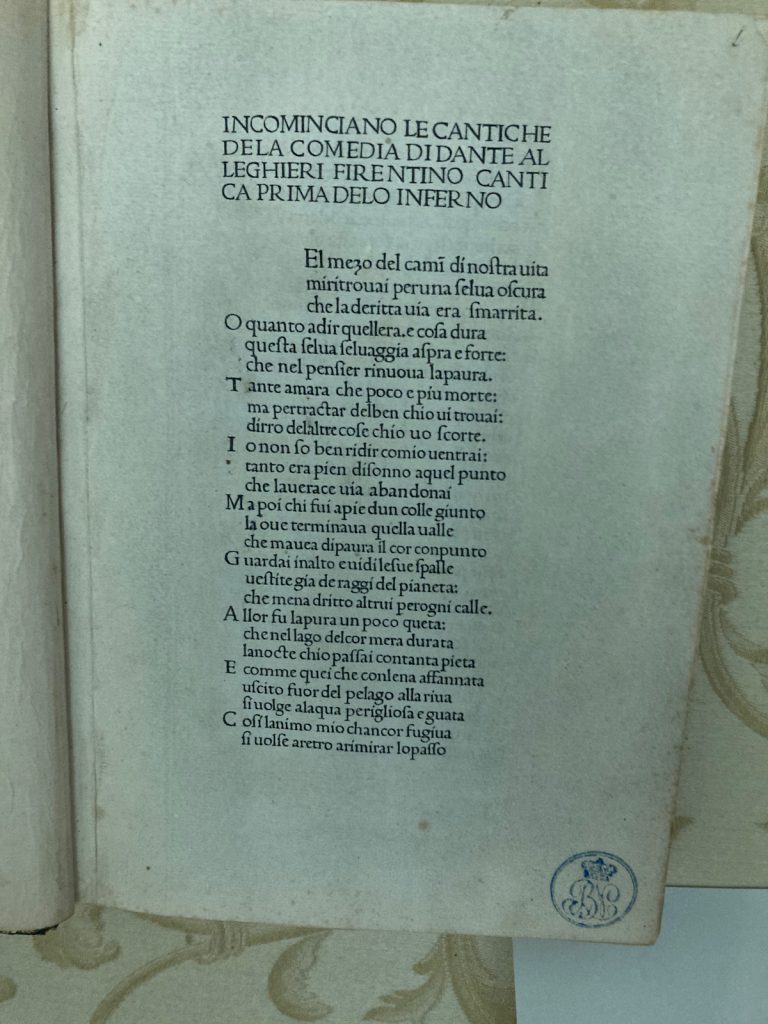

Morgan spends more time out of doors than in his house. He offers laconic remarks on the hills and vales, and recounts the significance of a Neolithic standing stone, the Dial Careg: one man’s deep-rooted oral history is another’s quaint folklore. Forsyth sorts through the books of his predecessor, the late Mr. Carlyon (a Cornishman who “read his head off”), found in a heap in one corner of the house: six-shilling novels, geology and engineering texts, books from Mudie’s circulating library, worm-eaten calf, and Arthur Machen. Forsyth begins reading a diary kept by Carlyon, the core of the novel, and this second frame becomes entangled with the story it encloses.

Undergrowth is a deft chronicle of sensations: the oppressiveness of the Mynydd Llwyd and Pen Savaddan, the mountains looming over the valley, and the menace of the tangled undergrowth filling its lower reaches, contrast with the tone of liberation in Carlyon’s diary and in the kinetic descriptions of climbing to the high ridges of Pen Savaddan and mountain meadows. The account of makeshift nursing during an epidemic in the work camp is rich in specific details of kindness and delirium. In Carlylon’s diary and in the latter portions of the novel the traces of Blackwood and Machen show clearest; the transcendent function of landscape in narrative anticipates Buchan, and the weather, too (I’m thinking of Richard Usborne’s observation in Clubland Heroes).

It’s not a perfect novel. There are unexplained shifts and the substrand of Morgan the shepherd is essential to the larger arc of the story, but he suddenly vanishes after uttering his curse. and sometimes it feels like the narrative escapes from the authors’ control (maybe not a bad thing, but occasionally puzzling). Undergrowth introduces the notion of older settlements and histories being drowned beneath the waters of a reservoir for a distant city (prefiguring “The Colour out of Space” by H. P. Lovecraft). The Elan Valley in Powys, with its “drowned villages”, is often mentioned as a possible setting for the Dulas valley of the novel.

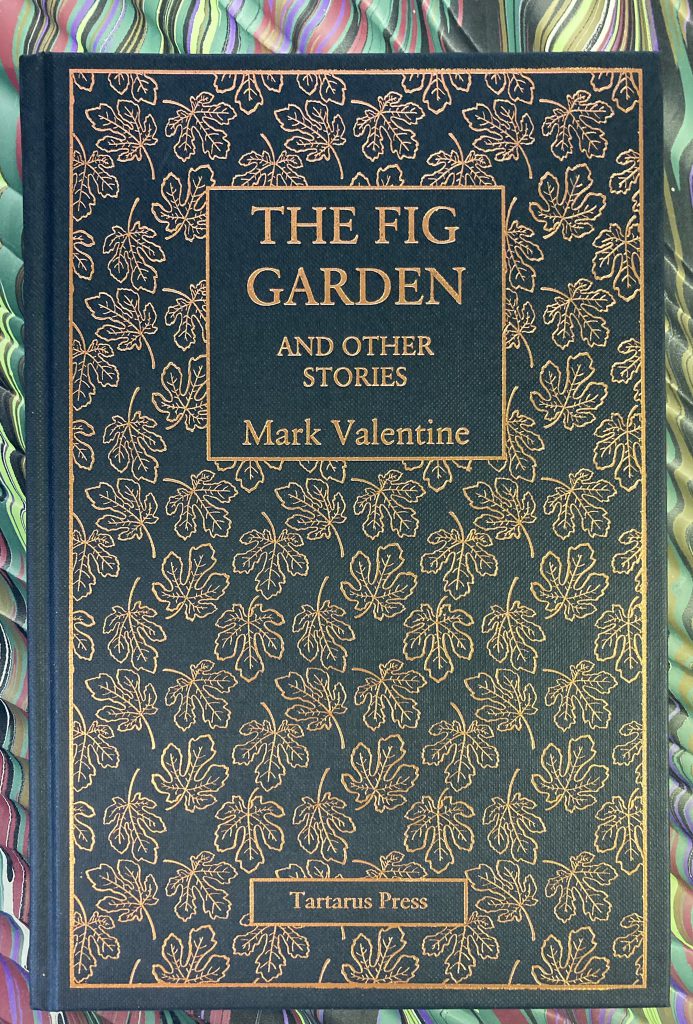

Undergrowth is a book I had been seeking for some time, repeatedly recommended by Mark Valentine, and I can see why. Valentine’s essay, “A Landscape At the End of the World: The Supernatural Terrain of Francis and Eric Brett Young”, gives an excellent overview of these writers an can be found in A Country Still All Mystery. Francis Brett Young was also author of Cold Harbour (1924), praised by Lovecraft.

The last chapter of Undergrowth is a rush of enthusiams and terrors and ambiguities. I think that one must read the story literally and join Forsyth in the snow on the Savaddan ridge to witness the vast lake “emptying itself in foaming masses above the broken masonry of the dam.”

NAPLES is a fine press edition of one of Avram Davidson’s darkest tales, originally published in the first Shadows anthology edited by Charles L. Grant. NAPLES won the World Fantasy award for short fiction in 1979, the same year Jorge Luis Borges was named the recipient of the World Fantasy Life Achievement award ; Davidson received that award in 1986.

NAPLES is a fine press edition of one of Avram Davidson’s darkest tales, originally published in the first Shadows anthology edited by Charles L. Grant. NAPLES won the World Fantasy award for short fiction in 1979, the same year Jorge Luis Borges was named the recipient of the World Fantasy Life Achievement award ; Davidson received that award in 1986.

—

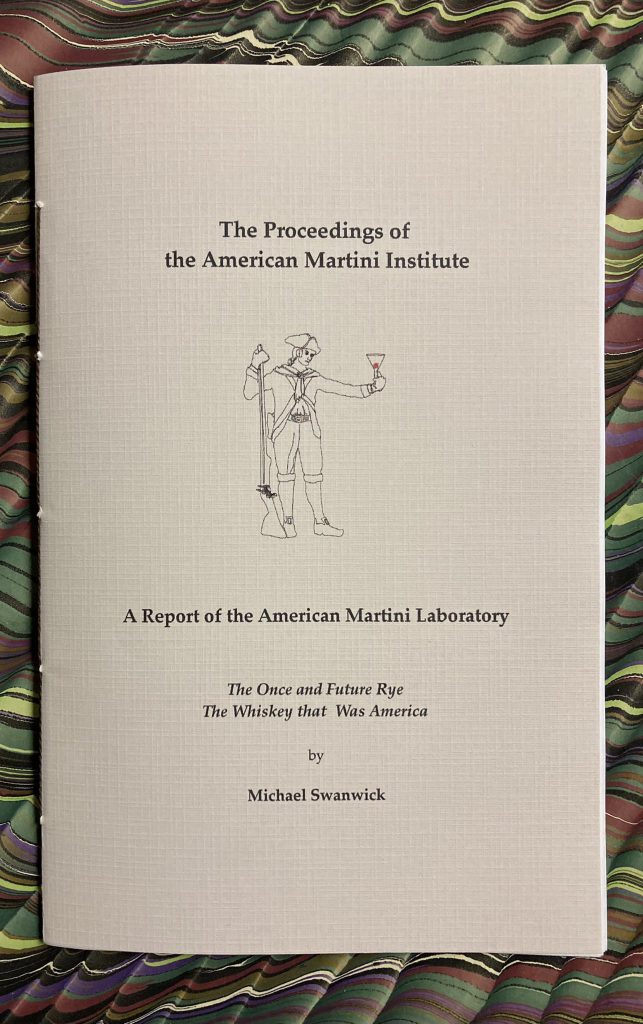

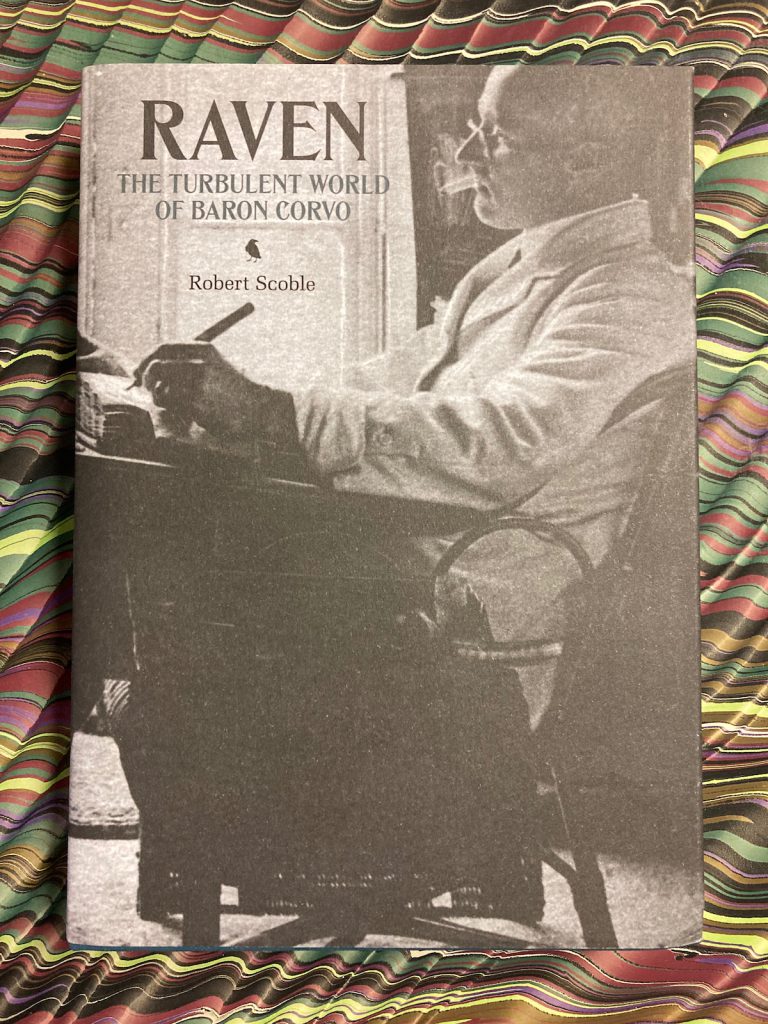

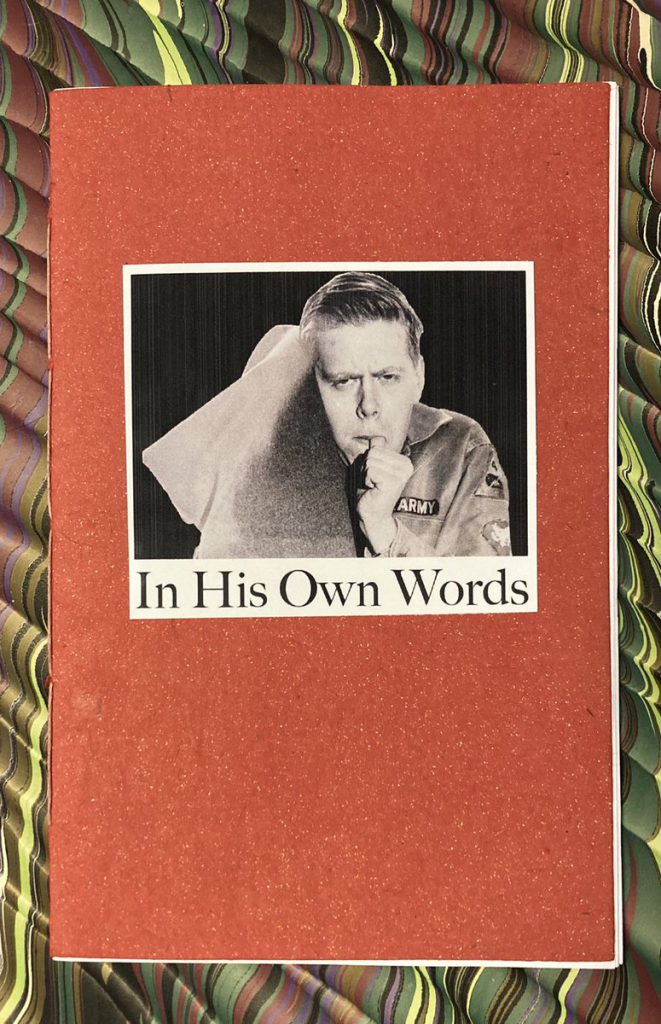

—  — Michael Swanwick and Gardner Dozois. In His Own Words. Dragonstairs, [2022]. Edition of 60 copies.

— Michael Swanwick and Gardner Dozois. In His Own Words. Dragonstairs, [2022]. Edition of 60 copies.