Friends,

today marks nineteen years of the Endless Bookshelf website. It was sunny and bitterly cold outside (the rhododendron leaves were tightly rolled) : a good day to be indoors with a book. I looked into Sir Thomas Browne’s Pseudodoxia Epidemica (sixth ed., 1672), and dug around in the chapters on the basilisk, bears, mermaids, dolphins, wolves, the phoenix (some of these I can see as touchstones for Avram Davidson). A pleasure to taste again Browne’s leisurely examination of delusions and sloppy thinking.

I have never been what they call a numbers driven person, so I don’t know what sort of “traffic” the ’shelf attracts (the newsletter list hovers around six hundred, and some recipients anyway may read theirs). But I do see occasional remarks or notes from readers, and on this occasion I reprint one which arrived by post last week :

I saw your post “Very Few Letters” and figured that was a good prompt for me to write you this short note.

There is no other site or place on ye olde internet that has provided me with as much continued enjoyment as the Endless Bookshelf. I continually return to the archives to discover new books or authors, and to read your good words.

My TBR pile/list always grows and I always somehow feel better after a visit. Weird, I know, but thought that a letter expressing my thanks might be welcomed.

— — —

Comments arrive at the Endless Bookshelf in many forms : a reader from California has just sent more than two dozen Seville oranges (pronounced in Shakespeare’s day as “civil as an orange” as Much Ado about Nothing reminds us). These will soon be transmuted into marmalade.

I will be in San Francisco at the end of February for the California International Antiquarian Book Fair, 27 February through 1 March at the Cruise Terminal building on the Embarcadero. I will be in booth 117 (Cummins). Say hello if you are there, and write if you would like a pass.

— — —

‘Lolly Willowes’ at 100

I wrote a centenary celebration of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes or the Loving Huntsman for Wormwoodiana (published earlier this week) :

http://wormwoodiana.blogspot.com/2026/01/sylvia-townsend-warners-lolly-willowes.html

— — —

recent reading

— Howard Waldrop. Masters of Science Fiction. Introduction by Paul Di Filippo. 1048 pp. Centipede Press, [2026]. Edition of 500 copies signed by Paul Di Filippo. Just began reading this giant compendium of stories from 1972 to 2005 : many familiar tales and some I haven’t seen before.

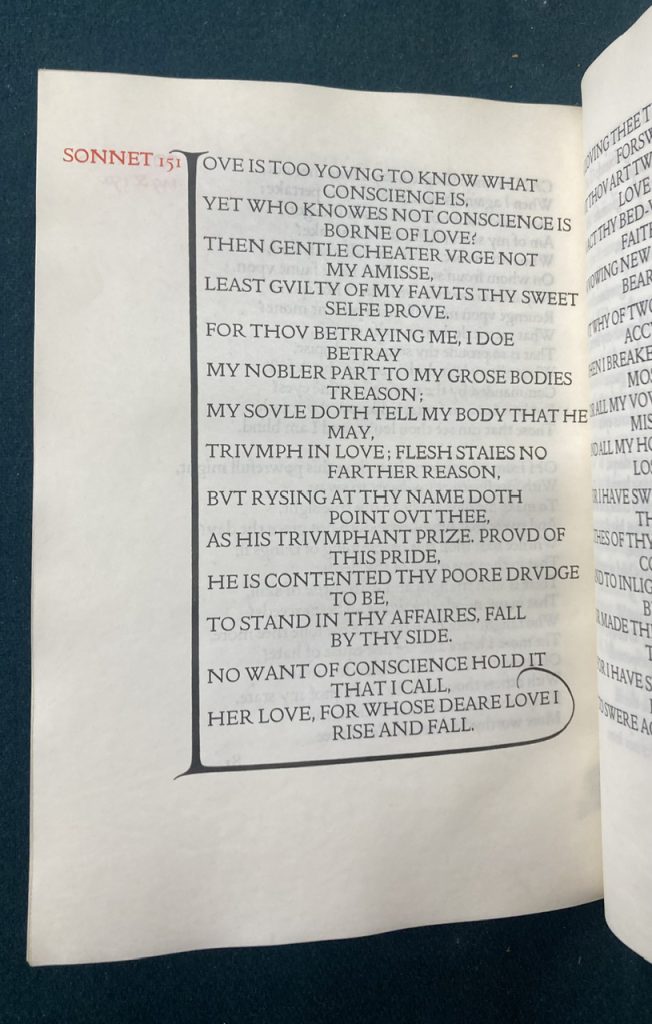

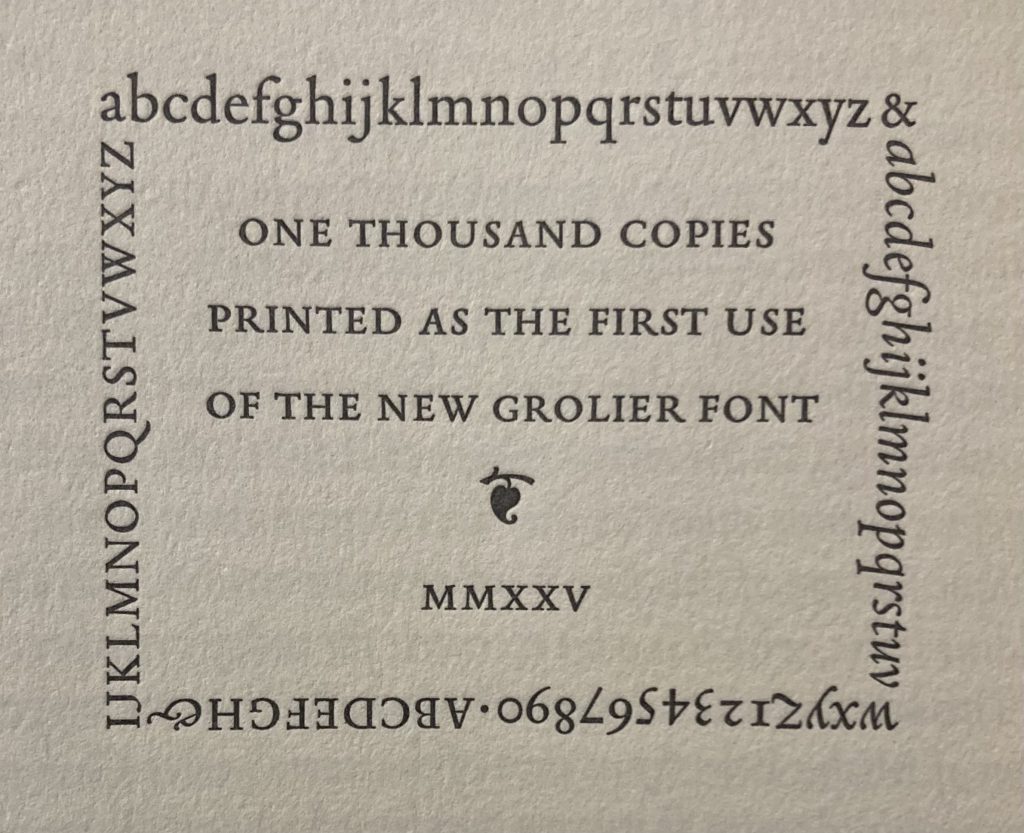

— [Charlotte Adams]. Jean Grolier [1884]. [Grolier Club, 2025]. Re-issue of an essay on collector Jean Grolier (1476-1565) from the earliest days of the club, designed by Jerry Kelly and the first use of his new Grolier typeface, based on the earliest roman and italic type cut by Francesco Griffo for Aldus Manutius. The colophon serves as a type specimen (though it does not show the tiny flourishes or extenders which also echo the early type forms).

— Tom La Farge. The Crimson Bears. Part One. A Hundred Doors. Part Two. Tough Poets Press, [2025]. I pulled the new edition from the shelf, started reading, and just kept going on from there. (I re-read the original edition last summer.) What a playful, sophisticated book.

— Ngaio Marsh. Artists in Crime [1938]. Penguin Books, [1957].

— — —

Thank you to all the readers. As always, send me your news or tell me about books I have overlooked.

— — —