Category: science fiction

recent reading : early august 2025

recent reading :

— Raymond Sokolov. Wayward Reporter. The life of A. J. Liebling. Harper & Row, [1980].

— R. B. Russell. T. Lobsang Rampa and Other Characters of Questionable Faith. Tartarus Press, [2025].

— E. F. Benson. Visible and Invisible. Hutchinson, [1923]. Collection of a dozen uncanny stories. The publisher’s catalogue (dated Autumn 2023) at the back lists this under new fiction : “Between our own and the other world lies a borderland of shadows, which eyes that can pierce the material plane may sometimes see.” Benson’s father (died 1896) was the late Victorian Archbishop of Canterbury ; his siblings were all very talented and eccentric. “Mrs. Amworth” is a nasty village vampire tale, deftly told.

In a centenary essay at Wormwoodiana, Mark Valentine notes Benson’s “sardonic glee in the macabre.” http://wormwoodiana.blogspot.com/2023/10/borderland-shadows-centenary-of-visible.html

— John Kessel. The Presidential Papers plus Imagining the Human Future : Up, Down, or Sideways plus The Last American and much more. PM Press, 2019. Outspoken Authors 31.

Includes “The Franchise” and Terry Bisson’s interview, and other satirical pieces. I saw John briefly at Readercon and he inscribed this “Critical of every president . . .”

— Paul Park. A City Made of Words plus Climate Change plus A Resistance to Theory and much more. PM Press, 2019. Outspoken Authors 23.

“A Conversation with the Author” and “A Resistance to Theory” are profoundly disquieting stories.

— A Soliloquy for Pan. Edited by Mark Beech. 372, [2] pp. Egaeus Press, 2025. Second edition (originally published 2015), with additional illustrations, adding one story, “The Game of the Great God Pan” by Benjamin Tweddell.

— Mark Samuels. Black Altars [2003]. Illustrations by Joseph Dawson. Zagava, 2025. Pictorial cloth. Elegant large format edition (12 x 7-1/2 inches) of this collection of six stories, a delight to hold in the hand and read.

— M. P. Dare. Unholy Relics. Edward Arnold, [1947] .

Collection of ghost stories in the tradition, though the plots are a bit coarser than anything from the pen of M. R. James ; and an exemplary work of literary misogyny couched in chivalrous postures. In that respect, Benson (see above) ain’t bad, neither.

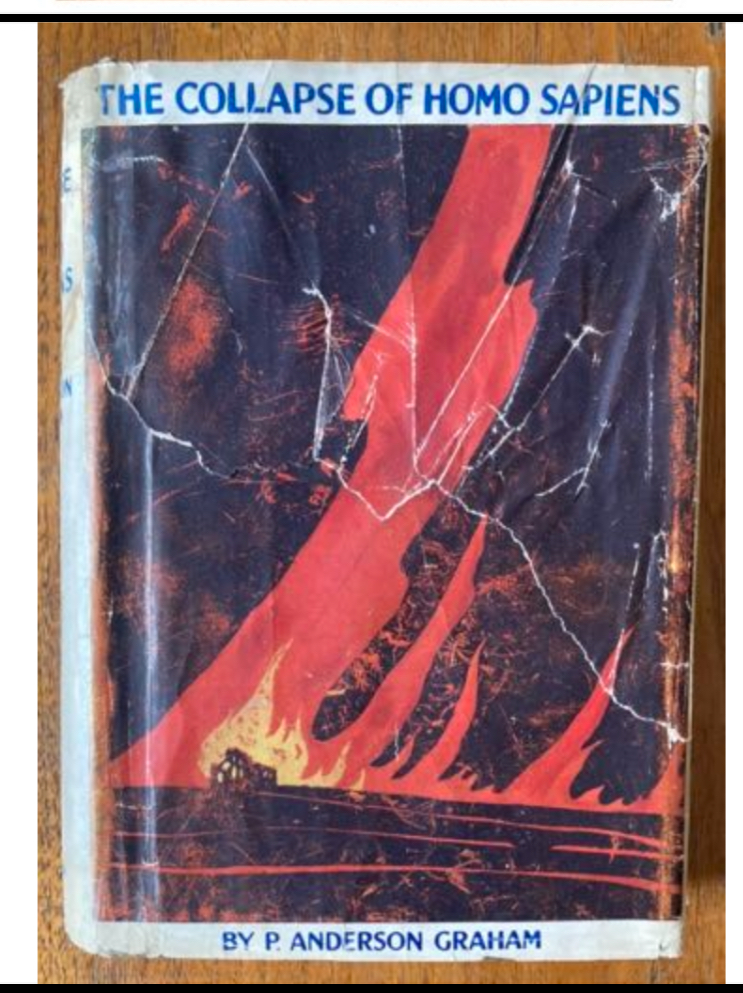

dust jackets and scientific romance

At Readercon in mid-July, the great delight was the panel / conversation with John Clute about dust jackets and the information they encode (in and out of science fiction), with examples from The Book Blinders (2024), my own collection, and the Clute Library at the Telluride Institute [click on things to see bigger pictures].

Clute also talked about the Scientific Romance in interwar British publishing, with Michael Dirda, a good chat. His thesis in progress is outlined at the SFE, lots of interesting titles (most of them in the Telluride hoard), details here :

https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/scientific_romance

![The World Ends by William Lamb [Storm Jameson] (dust jacket from the Clute collection, Telluride)](https://endlessbookshelf.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/IMG_2042.jpeg)

recent reading : late june 2025

recent reading : late june

— Paul McAuley. A Very British History. The Best Science Fiction Stories of Paul McAuley, 1985-2011 [and:] . . . (Additional Stories). 2 vols. PS, 2013. Cover art by Jim Burns. Edition of 200 copies, signed by the author.

What a range of tone and subject, from far future urban sass and space drama to life in the ruins ; and McAuley’s hard science fiction as often engages political as scientific speculation. “Second Skin” (1997) and “Rocket Boy” (2007) are excellent hard tales; and “Cross Road Blues” (1991) and “The Two Dicks” (2001) are choice entries in the line of subversive British literary pastiches of American popular culture — I am thinking of “The Big Fish” or Back in the USSR by Byrne and Newman, and similar delights — indisputably, Howard Waldrop was read over there east of the Atlantic ocean.

“How We Lost the Moon, A True Story by Frank W. Allen” (1999) is great, Nevil Shute in space, with a fine ending. [This is high praise, not a dig : Jack Vance made a whole late career cycle of Wodehouse in space.] “A Very British History”, published in Interzone in 2000, is a review of an imaginary book worthy of Lem, but only a tricky Brit could have rung this particularly bell so clearly.

The world-building in the stories is sly and integral. As in the novels, the dance of ideas includes gestures or flourishes that would be infodumps in other hands : McAuley knows when to let an idea go as a flash or hint. I had read Fairyland and a few other novels ; reading War of the Maps earlier in the month prompted me to look at the short stories.

— Michael Swanwick. [Singular Interviews] S1ngular 1nterv1ews. Dragonstairs Press, 2025. Edition of 60 copies signed by the author. Stitched in Indian paper wrappers of various hues, with title label.

Michael Swanwick is the originator of the Singular Interview (many were published in the New York Review of Science Fiction). When he asks a single question, people answer: John Crowley, Tom Purdom (a witty joke), Eileen Gunn, Gregory Frost, Paul Park, Mike Resnick, Samuel R. Delany, Karl Schoeder, David Hartwell, Henry Wessells, Greer Gilman, Spider Robinson, Fran Wilde, Tom Purdom (a serious answer this time), and Michael Moorcock.

[It is a useful conceit, and I have borrowed it on several occasions). The edition sold out almost immediately, as usual with this press (see me after class if you need a copy)].

Readercon 34 (July 2025)

Readercon 34 Schedule

at the Boston Marriott Burlington in Burlington, Mass.

https://readercon.org

Saturday 19 July

10:00 a.m., at the autographer’s table

Autograph Session : Henry Wessells

Sunday 20 July

10:00 to 11:00 a.m., in : Create / Collaborate

The Art of the SF Book Cover

John Clute & Henry Wessells

Panel description : Since its inception, the British Library, the national library of the UK, has stripped dust jackets off books in its holding and discarded the unwanted wrappers, losing an essential piece of their cultural and artistic significance. In The Book Blinders, science fiction historian and theorist John Clute details the “annals of vandalism” at the British Library, with a focus on works lost (and found). John Clute and antiquarian bookseller Henry Wessells give a joint presentation on this subject, with numerous illustrations, and with extra time for Q&A.

11:00 to 11:30 a.m., in : Empower / Embrace

Reading : Henry Wessells

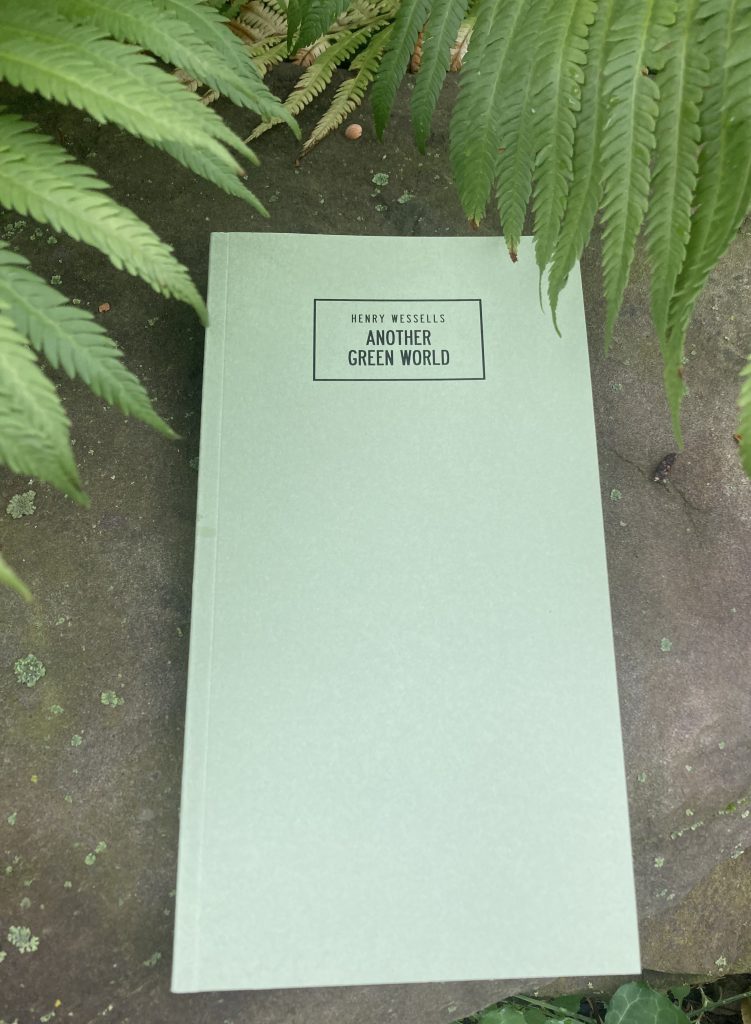

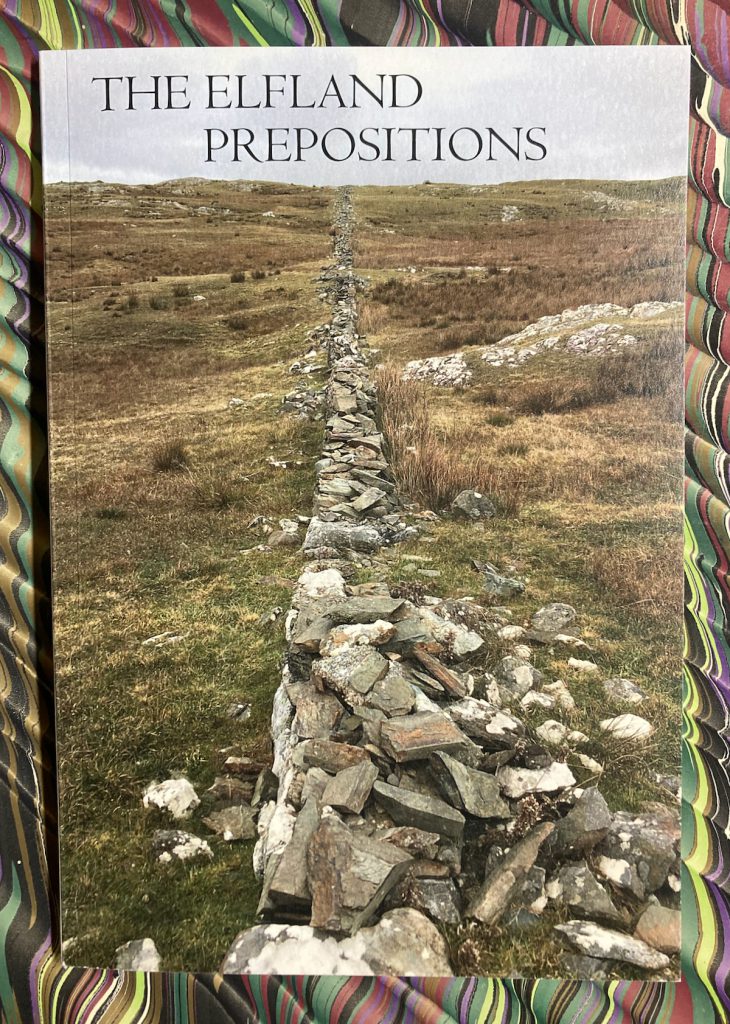

Henry Wessells reads from The Elfland Prepositions and from Another Green World (both newly published in 2025).

12:00 noon to 1:00 p.m., in : Create / Collaborate

The Art of the SF Book Cover

John Clute & Michael Dirda

Panel description : The early divergence of American and British science fiction may best be witnessed in the works of UK authors in the 1930s and ’40s that have been called “scientific romances.” Unlike their pulp cousins in the US, these works lack the optimistic outlook of young square-jawed heroes out to conquer the galaxy. Instead, they offer anxiety about rogue scientists armed with Ultimate Weapons out to blackmail the world to either peace or servitude. In this presentation, famed fantastika theorist John Clute and Michael Dirda will discuss this less-recognized strand of SF.

[N.B. I will be running a slide show not dissimilar to the one for dust jackets.]

I should arrive at Readercon by midday on Friday. Temporary Culture will have a table in the book room on Friday and Saturday, and copies of A Conversation larger than the Universe, The Private Life of Books, The Elfland Prepositions, and Another Green World (advance copies of the Zagava paperback), the publications of the Avram Davidson Society, Sexual Stealing by Wendy Walker, and a variety of other books will be available for sale (cash, cheque, or paypal). If you see me, come say hello. There is always plenty of time for conversation.

Another green world by Henry Wessells, 2025

— Henry Wessells. Another green world. Zagava, 2025. Paperback issue. Pp. 180, [2, blank], [2, imprint]. Sage green wrappers printed in black, lower wrapper with blurbs by Guy Davenport, William Gibson, and Joanne McNeil.

On a very hot evening in late June, your correspondent went to Newark airport to expedite customs clearance and collect the first author copies of Another green world, newly re-issued by Zagava Books with two additional stories. It is a stylish book in a tall narrow format, set by Jan-Marco Schmitz in Minion pro with titles in Roadway.

The paperback is a pleasure to hold and read. The hardcover issue is in production, and a formal announcement of publication is expected. Zagava make nice books. Perhaps you will agree.

The table of contents is as follows (with note of the story‘s first publication) :

- From This Swamp. (The Starry Wisdom. A Tribute to H. P. Lovecraft. Ed. D. M. Mitchell. Creation Books, 1994)

- Book Becoming Power. (NYRSF, March 2000)

- Another Green World. (Nature, 15 June 2000)

- The Polynesian History of the Kerguélen Islands. (Exquisite Corpse 45 & 47, 1994)

- The Institute of Antarctic Archaeology & Protolinguistics. (Another green world, 2003)

- Appraisal at Edgewood (A Critical Fiction). (NYRSF, March 2001)

- Hugh O’Neill’s Goose. (Interzone, October 2001)

- Virtual Wisdom. (Exquisite Corpse 36, 1992)

- Wulkderk; or, Not in Skeat. (Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet 32, 2015, as “The Beast Unknown to Heraldry”)

- Extended Range; or, The Accession Label. (2015, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet 35, 2016)

- Ten Bears; or, A Journey to the Weterings (A Critical Fiction). (NYRSF, October 2003)

Of the first edition, Guy Davenport wrote,

“If you don’t believe in magic, read Henry Wessells and find out how wrong you are.”

Joanne McNeil (author of Lurking and Wrong Way), writes, “Henry Wessells writes from beyond an ‘unfamiliar void’, where the natural world, dreams, language, myths, research, and rituals converge. The stories collected in Another Green World offer uncanny vitality out of the dark like dandelions sprouting from cracked New Jersey pavement. A delightful and enduring work of literary inquiry.”

commonplace book : february 2025

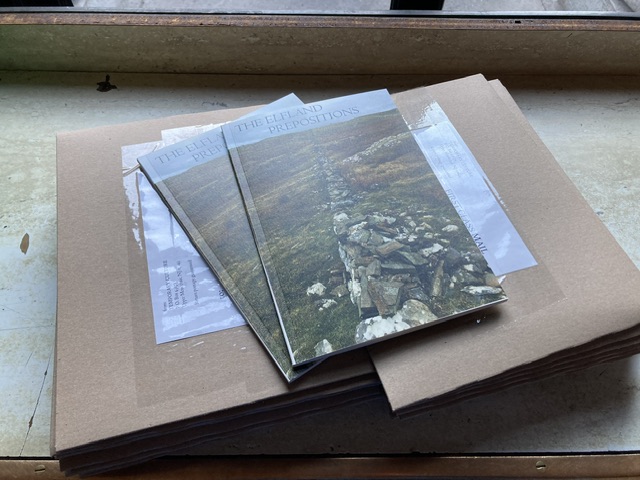

The Elfland Prepositions, published 27 February

advance presentation copies, at the post office ready for mailing [26 February]

—

in production

— Henry Wessells. The Elfland Prepositions. Temporary Culture, 2025.

Printed on Mohawk superfine white eggshell. Pictorial wrappers. 26 copies, lettered A to Z, were reserved for presentation ; there were also 100 copies numbered 1 to 100.

Proof copy above (received 12 February 2025) ; proofs corrected & in production (14 February 2025), published 27 February 2025.

Copies now offered for sale, click on link or photo to order.

ISBN13 978-0-9764660-0-0 ISBN 0-9764660-0-1

Collection of four previously unpublished short stories.

Elfland is not a nice place, but it’s important to know how it works.

— — —

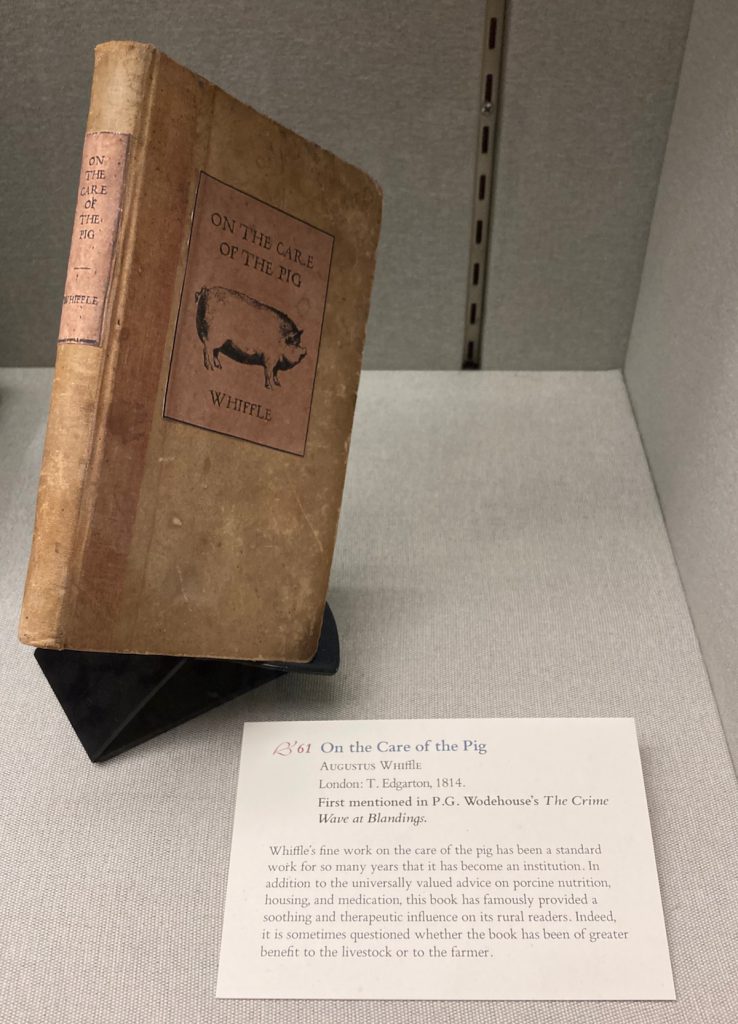

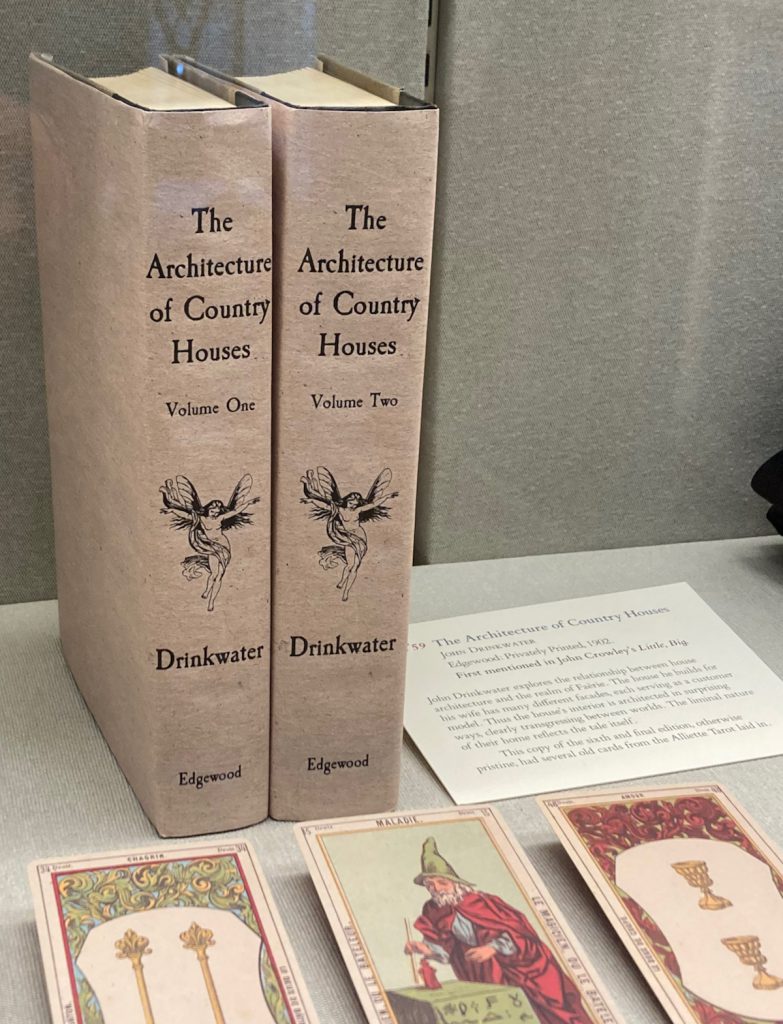

seen in the imagination, and at the Grolier Club :

two entries from the recent Grolier Club exhibition, Imaginary Books. Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works Found Only in Other Books, from the collection of Reid Byers.

— — —

current reading

— Charles Robert Maturin. Melmoth the Wanderer: A Tale [1820]. With introduction and notes by Victor Sage. Penguin Books, [2000].

/ into the labyrinth, again

— — —

recent reading

— Len Deighton. Hope. HarperCollins, [1995].

— — Charity. HarperCollins, [1996].

— — Winter. A Novel of a Berlin Family. Knopf, 1987.

Germany in the world, 1899-1945 ; back story or bedrock for the Bernard Samson novels.

— — —

‘away from the clank of the world’

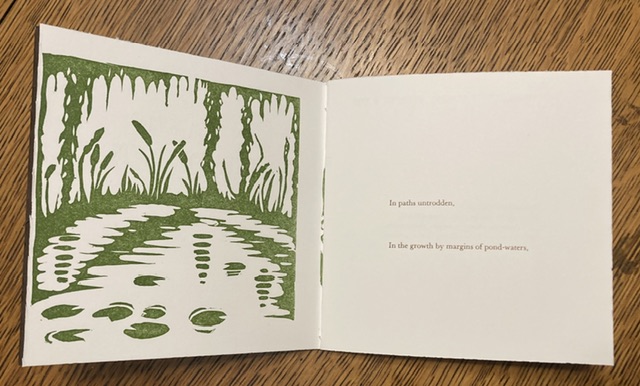

— Walt Whitman. In Paths Untrodden. Printed in brown ink, blockprint illustrations in green and blue. [16] pp. [The Letterpress at Oberlin, January 2025]. Edition of 217.

Calamus 1, from the 1860 Leaves of Grass, with blue herons and green marsh plants. [Gift of VH].

— — —

Hard Rain by Janwillem van de Wetering

A short note now up (in English) on the excellent and informative Dutch site

https://janwillemvandewetering.nl/favoriete-boek/

— — —

“not relics of the past, but pockets of the future arriving ahead of schedule”

— Christopher Brown, over at The Clearing (the blog of Little Toller Books)

— — —

“When I look at that obscure but gorgeous prose-composition, the Urn-burial, I seem to myself to look into a deep abyss, at the bottom of which are hid pearls and rich treasure ; or it is like a stately labyrinth of doubt and withering speculation, and I would invoke the spirit of the author to lead me through it.”

— Charles Lamb on Sir Thomas Browne, quoted by Hazlitt, in “Of Persons One Would Wish to Have Seen” (1826)

— — —

Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford : the Endless Bookshelf book of the year – 2024

Another green world by Henry Wessells

Zagava Books will be publishing Another Green World, a collection of short fiction expanded from the 2003 work with the same title and adding two previously uncollected stories. The book will be available in two states, a narrow format paperback and a numbered hardcover. Another Green World is in production for late spring 2025 and can be pre-ordered here :

https://zagava.de/shop/another-green-world

The table of contents includes the following stories :

- From This Swamp (1,800 words)

- Book Becoming Power (2,200 words)

- Another Green World (800 words)

- The Polynesian History of the Kerguélen Islands (3,300 words)

- The Institute of Antarctic Archaeology & Protolinguistics (3,600 words)

- Appraisal at Edgewood (2,000 words)

- Hugh O’Neill’s Goose (3,800 words)

- Virtual Wisdom (900 words)

- Wulkderk; or, Not in Skeat (1,750 words)

- Extended Range; or, The Accession Label (2,000 words)

- Ten Bears (8,400 words)

Of the first edition, Guy Davenport wrote,

“If you don’t believe in magic, read Henry Wessells and find out how wrong you are.”

Mark Valentine writes : “Henry Wessells delights in books and mysteries and writes with a zest for the arcane and a talent for the oblique and surprising.”

Zagava produce beautiful books and I am delighted to join the ranks of their authors.

Postcard from Armadillocon 46

A fun trip down to Austin to see old friends, attend Armadillocon, make new friends, eat good vegan food, and, as usual, look at books. (This is one of those postcards that gets mailed after leaving the place.) I hadn’t been to Austin or Armadillocon for several years, so it was good to be back. A curator friend recommended a vegan sushi place Nori. I headed there after our meeting and was impressed by the Katana-ya (deep-fried nori roll with avocado, cucumber, kanpyo, shoga, surimi mix; topped with wasabi mayo, unagi, ponzu green salad, jalapeño, red onion, and cilantro). The convention was in the same hotel as before, an odd, anonymous late 1970s exurban architectural mode that could have been at the edge of Anywhere, USA. Inside, though, it was all Armadillocon, a small friendly convention with a good mix of panels and readings (even sometimes forcing one to make hard choices).

One of the reasons I went was to show up at the Howard Waldrop celebration, a panel moderated by Scott A. Cupp and also including Sanford Allen, Robert Taylor, and Don Webb: all friends who knew Howard for decades. I hadn’t been able to attend the Waldrop Memorial in June; I was glad to attend this gathering. Towards the end of the allotted hour (the anecdotes and yarns could have gone on for hours), when the floor was open for comments, I stood up and said something like this:

My name is Henry Wessells and I’m from New Jersey, where we also esteem Howard Waldrop. He excelled at integrating incompatible ideas into improbable fictions that suddenly reveal truths about life, literature, and America; and the stories equally suddenly show themselves to be inevitable and essential parts of American literature. If “The Ugly Chickens” is often mentioned as Howard’s best known story, for me his masterpiece is “Heart of Whitenesse”, where the ambitious conceit is executed with perfect skill. Not a word out of place, and the madcap humor is controlled in the service of the tale.

I have it from a reliable source that as an angler Howard practiced catch and release, and thus understood the impossibility of clinging to things. And so we now mark his departure; the stories, and the ideas, remain.

— Christopher Brown. Field Notes. September 2024. [Austin, 7 September 2024]. Gift of the author, inscribed, one of the first copies out of the box. Two essays, two reading lists, and twelve photos. Newsletter for advance orders to his new book.

——. A Natural History of Empty Lots. Timber Press, [September 2024]. Advance copy, inscribed.

—. Live to Build a Better World. Despair, Survival, and Hope in Science Fiction’s Response to Environmental Change. [Introduction by Jeremy Brett]. Texas A&M University Libraries, 2021. Illustrated catalogue for the exhibition at the Cushing Memorial Library (January to June 2021). An interesting selection of mostly twenty-first century books and films, with the earliest titles being The Lorax (1971), by Dr. Seuss, Brunner’s The Sheep Look up and Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest (both 1972), and Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower (1993).

— Avram Davidson. The Avram Davidson Treasury. Tor, [1998]. Book club edition which I hadn’t known existed. The copyright page is altered, the dust jacket carries no price and has a number slug on the back panel, and the black boards are smooth.

— Delilah S. Dawson. Bloom. Titan, [2023].

— Joe R. Lansdale. Things Get Ugly. The Best Crime Stories of Joe R. Lansdale. [Introduction by S. A. Cosby]. Tachyon, [2023].

— Josh Rountree. Death Aesthetic. Underwood, [2024].

——. The Legend of Charlie Fish. Tachyon, [2023].

— John Varley. The Persistence of Vision. [Introduction by Algis Budrys] [1978]. Dell [Quantum Paperback], [1979]. Varley was the first Armadillocon guest of honor.

— Howard Waldrop. Howard Who?. Stories [1986]. Peapod Classics. [Small Beer Press, third printing, 30 March 2024] [replacement copy].