far fetch :

— Mark Tewfik. Two Weeks in Ecuador and the Galapagos [drop title]. [8] pp. Santa Cruz, Galapagos Islands : Lanterne Rouge Press, 2025. Printed self wrapper with ornamental headpiece.

Fun travelogue with a truly exotic imprint, even for this peripatetic press.

and at the foot of the last page, the imprint, below :

— — —

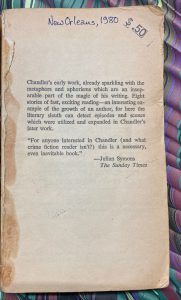

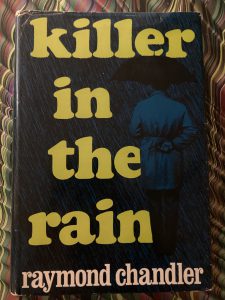

— Raymond Chandler. Killer in the Rain. With an introduction by Philip Durham. [1964]. Ballantine Books, [1972].

This book collects eight early pulp stories Chandler which had refused to reprint in his lifetime, because he had “cannibalized” them and transformed the raw material into the substance of three novels : The Big Sleep ; Farewell, My Lovely ; and The Lady in the Lake. Reading it was an education and single dose corrective to prose excesses rooted in obsessive teenage readings of H. P. Lovecraft. This copy, bought for 50 cents at the State Street Book Mart, a paper back exchange shop in New Orleans, has stuck with me for many years.

After re-reading parts of MacShane’s Life of Chandler, I pulled down Killer in the Rain to look at some of the stories, and it will not survive this reading. I will save the browned flyleaf and title page for a bookmark in a copy of the original Houghton Mifflin printing I bought last month : so I still havea copy of Killer in the Rain ; and I will wait for a stormy day to say farewell to Killer in the Rain in the rain ; but the small gap on the paperback shelf will stay open for a time.

— — —

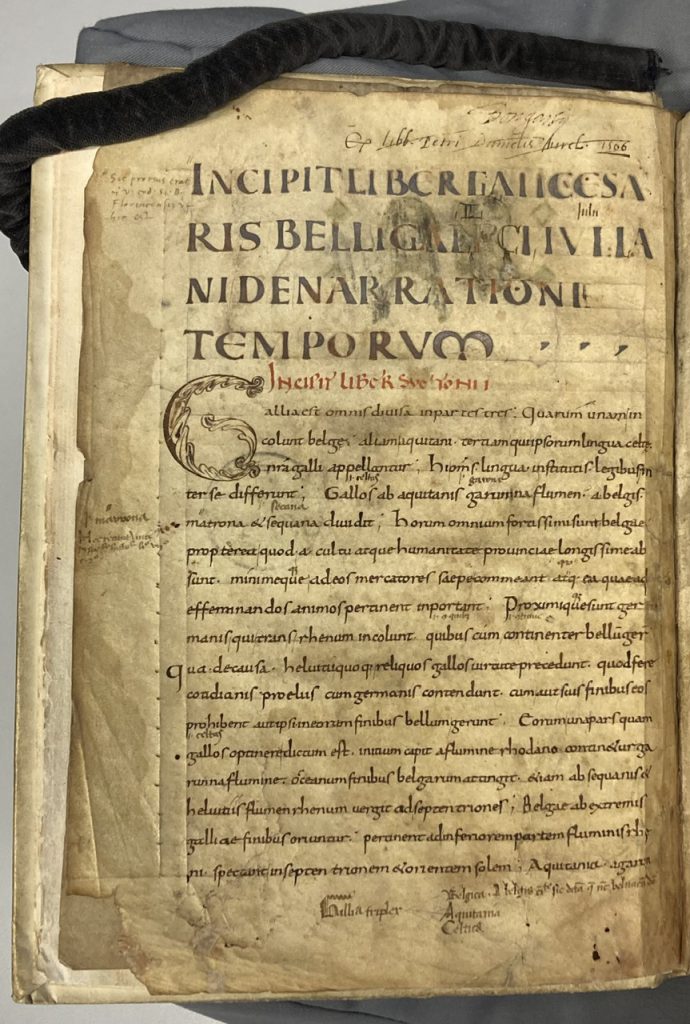

from the Epigrammata of Martialis (Epigrams of Martial)

Lucanus

Sint quidam qui me dicunt non esse poetam :

Sed qui me vendit bibliopola putat.

Lucan

[Some say I am no poet : but the bibliopole* sells me as one]

* – bookseller, for you moderns, sez Old ’Pole

— — —

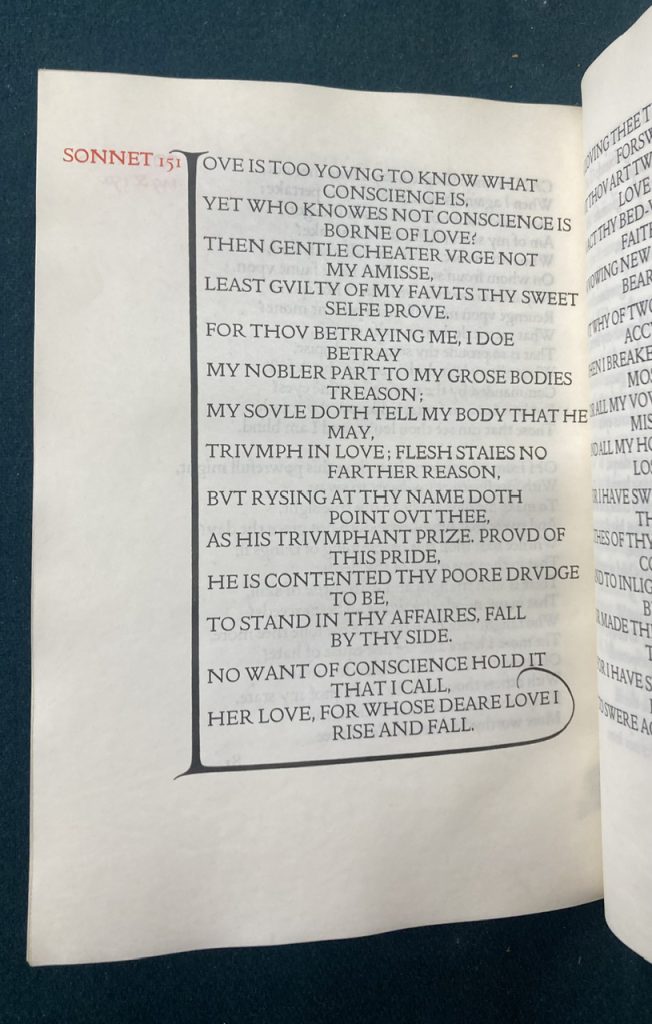

Sonnet 151 with initial L by Edward Johnston, in the Doves Press edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, 1909.

— — —

— — —

‘Pardon this intrusion’

The first words the monster speaks, in vol. II of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Philadelphia : Carey, Lea & Blanchard, 1833.

— — —

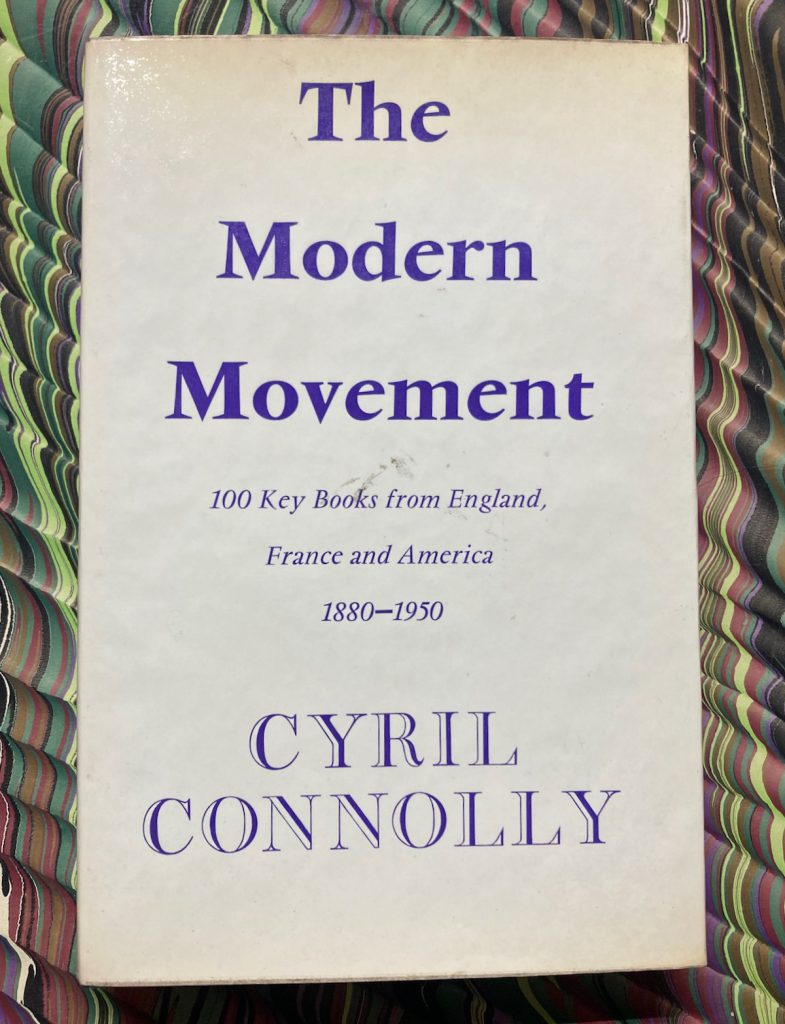

recent reading :

— J. I. M. Stewart. Myself and Michael Innes. A Memoir. W. W. Norton, [1988].

— Charles Willeford. Everybody’s Metamorphosis. Dennis McMillan, 1988. Edition of 426 copies signed by the author.

— Dorothy L. Sayers. Whose Body ? A Lord Peter Wimsey Novel [1923]. Harper & Row, [n.d., ca. mid-1950s]. Dust jacket design by Shirley Smith.

— Hilary Spurling. Invitation to the Dance. A Guide to Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time. Little, Brown, [1977].

— Margery Allingham. The Case of the Late Pig [1937]. Penguin Books, [1957].

— — —

Cat and Girl in Oz

Dorothy Gambrell’s Cat and Girl are somewhere in Oz. They started on the yellow brick road here :

https://catandgirl.com/were-off-to-see-the-boss-class/

— — —

Erin Kissane’s remarkable essay on the geophyics of the 1964 tsunami at Valdez, Alaska, and her extrapolations to articulate a brilliant, useful metaphor for the post-information age :

https://www.wrecka.ge/landslide-a-ghost-story/

— — —

“Two sculptural titans are thus now fittingly face-to-face, Rodin the culminating figure of an ancient representational tradition that was revived during the Renaissance and Calder the initiating figure of a modernist reconception that took the medium off its pedestal.”

— Martin Filler, from his review of the Calder Foundation gardens in Philadelphia, in the New York Review of Books .

[what a sentence ! 2,500 years of art history in a single swoop]

Andromeda

Now Time’s Andromeda on this rock rude,

With not her either beauty’s equal or

Her injury’s, looks off by both horns of shore,

Her flower, her piece of being, doomed dragon’s food.

Time past she has been attempted and pursued

By many blows and banes ; but now hears roar

A wilder beast from West than all were, more

Rife in her wrongs, more lawless, and more lewd.

Her Perseus linger and leave her tó her extremes ? —

Pillowy air he treads a time and hangs

His thoughts on her, forsaken that she seems,

All while her patience, morselled into pangs,

Mounts ; then to alight disarming, no one dreams,

With Gorgon’s gear and barebill, thongs and fangs.

from : Gerard Manley Hopkins. Poems (Oxford, 1918).

— — —

![The World Ends by William Lamb [Storm Jameson] (dust jacket from the Clute collection, Telluride)](https://endlessbookshelf.net/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/IMG_2042.jpeg)