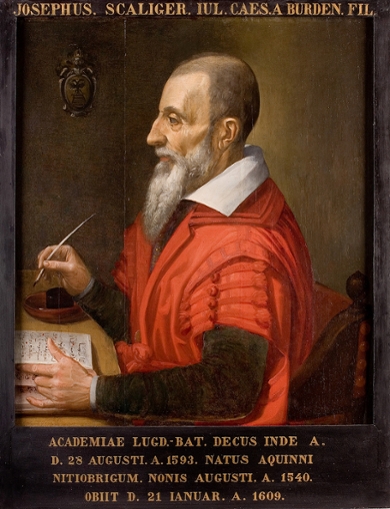

— Kasper van Ommen. “The Einstein of the sixteenth century”, in : Books That Made History. 26 Books from Leiden That Changed the World. Edited by Kasper van Ommen and Geert Verhoeven. [Translated by Claire and Mike Wilkinson]. Brill, 2022.

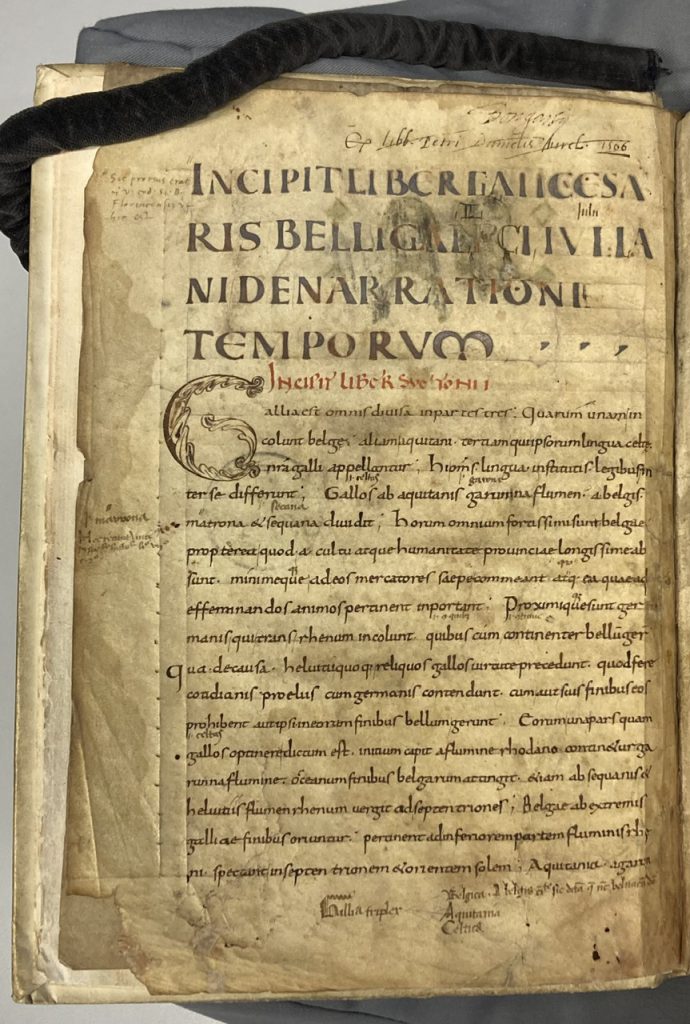

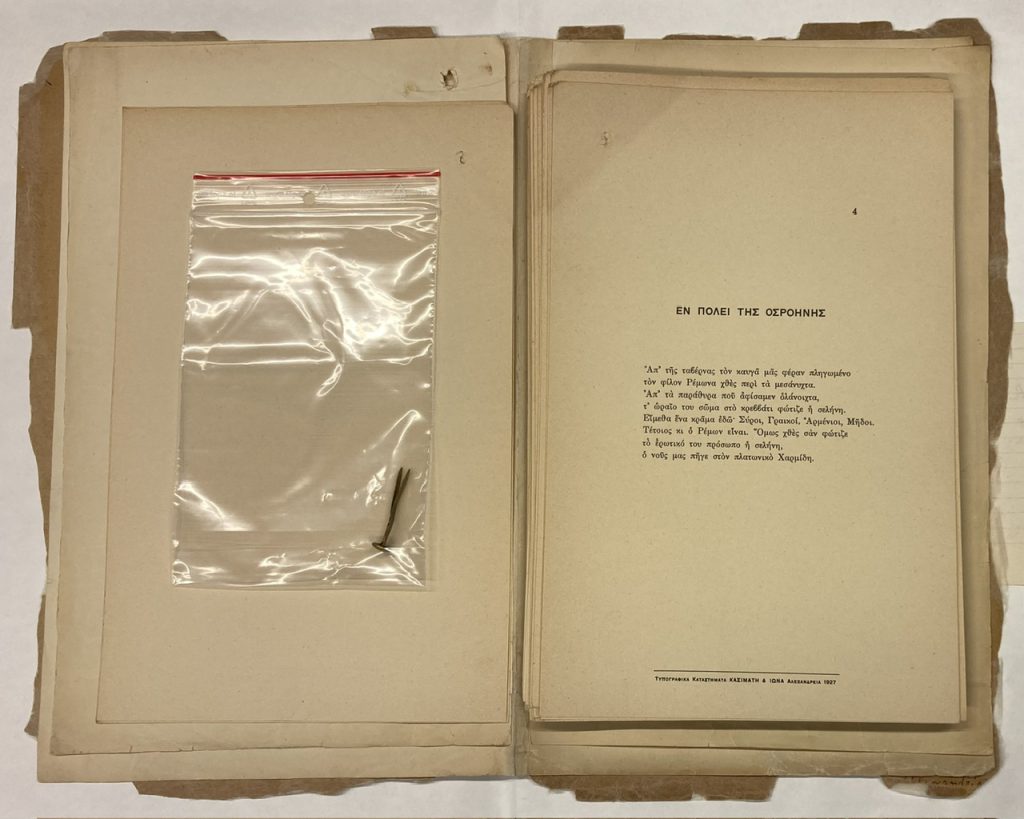

Excellent essay on J. J. Scaliger (1540-1609), polyglot scholar of classical and near eastern languages, whose Opus de emendatione temporum (1598) integrated astronomy and history from Jewish, Babylonian, Persian and Egyptian sources as well as Greek and Roman works ; “he also incorporated the latest astronomical understandings of Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) and Tycho Brahe (1546-1601)”. Scaliger came to Leiden University with his library in 1593; it soon grew, and has been kept there ever since. Your correspondent is the lowest amateur polyglot in the presence of such erudition; there were some remarkable books on view during a visit last week (including a presentation inscribed from Brahe to Scaliger).

A summary note on Scaliger’s career by van Ommen on the University website (Dutch for ‘grouch’ is brompot), Josephus Scaliger : famous scholar and grouch

— — —

— Janwillem van de Wetering. Hard Rain [1986]. Soho paperback, [1997].

Had to pick this one up again, an old favorite by an old friend, for a re-read now that I have been to Amsterdam, and have walked and bicycled along the canals and into the Amsterdamse Bos. It was a Depression-era landscaping project around the Olympic rowing basin of 1928 and is now a mature city forest and a green lung in the midst of a densely populated zone.

— — —

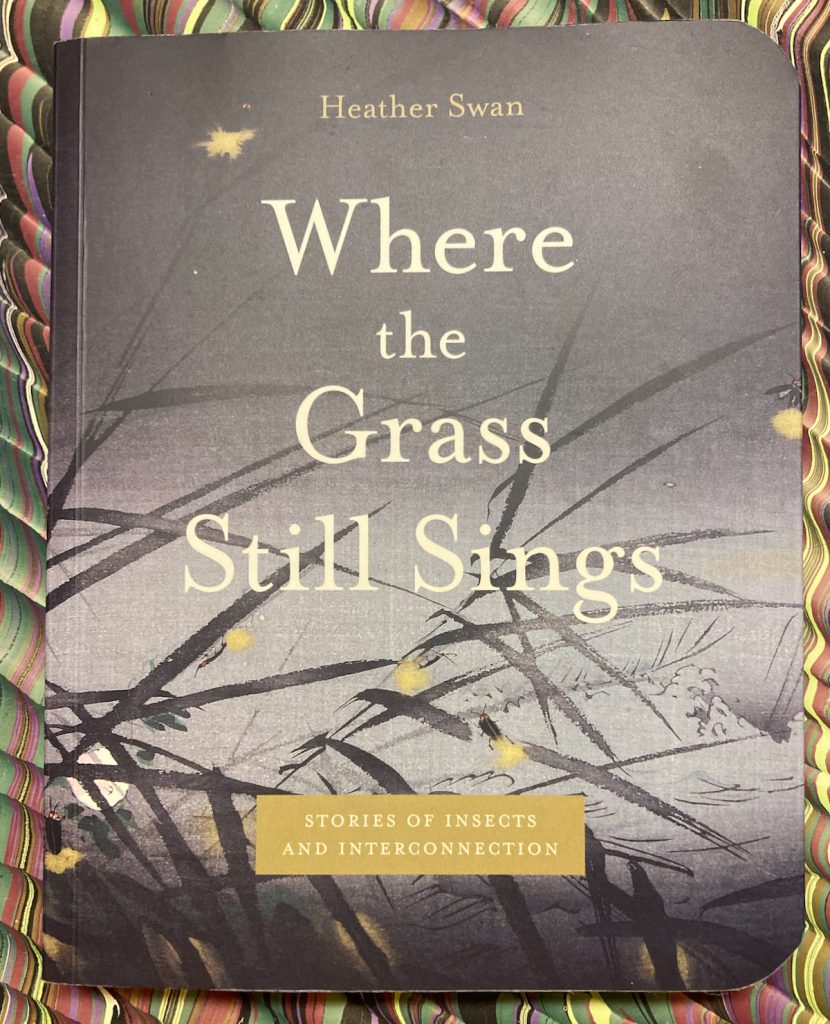

— Heather Swan. Where the Grass Still Signs. Stories of Insects and Interconnection. Pennsylvania State University Press, [2024].

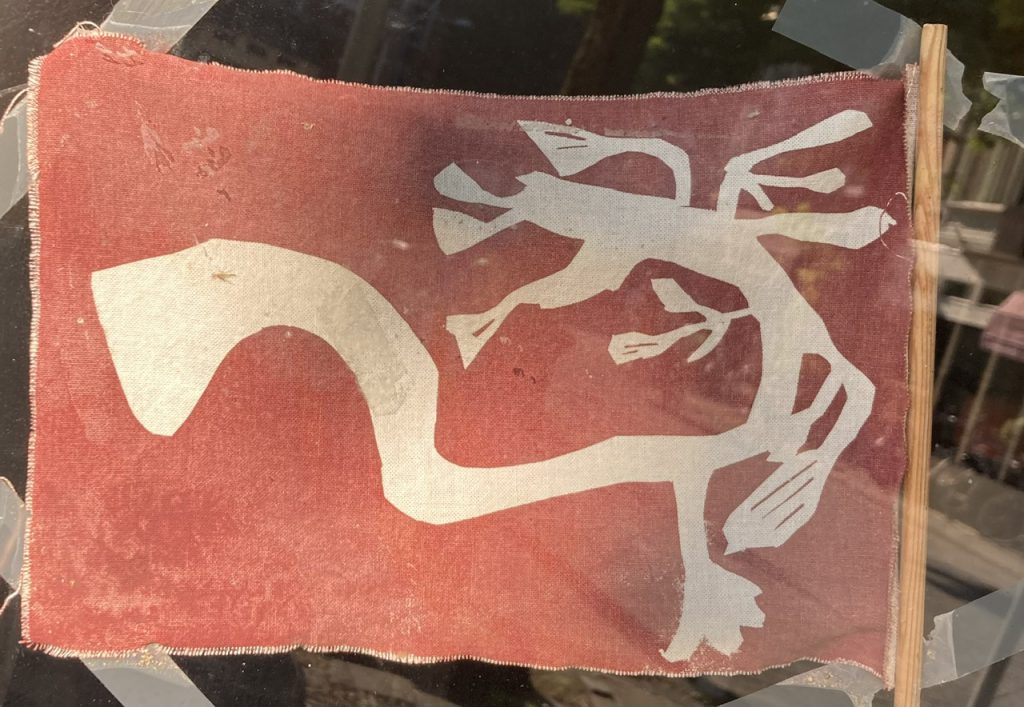

Memoir and travelogue on insects and landscapes from the rural midwest to Colombia and Ecuador, richly illustrated with works by contemporary artists. Seen in the window of Architectura & Natura, an inviting bookshop on Leliegracht in Amsterdam.

— Christian de Pange. Le Bréviare du Quintivir. Une enquête bibliographique en Franche-Comté. [Lusove: Imprimerie de Bacchus] Pour la Société des Bibliophiles Francois, 2022.

Bibliographical account of a private social club in Vesoul in rural France at the turn of the nineteenth century, and their festive book, printed circa 1813 for the five members. The bibliographer has traced three copies to the present day; a fourth copy was last seen in 1896. Edition of 100 copies, from the author.

— Choosing Vincent. From family collection to Van Gogh Museum. Lisa Smith and Hans Luijten (eds.). Van Gogh Museum / Thoth Publishers, [2023].

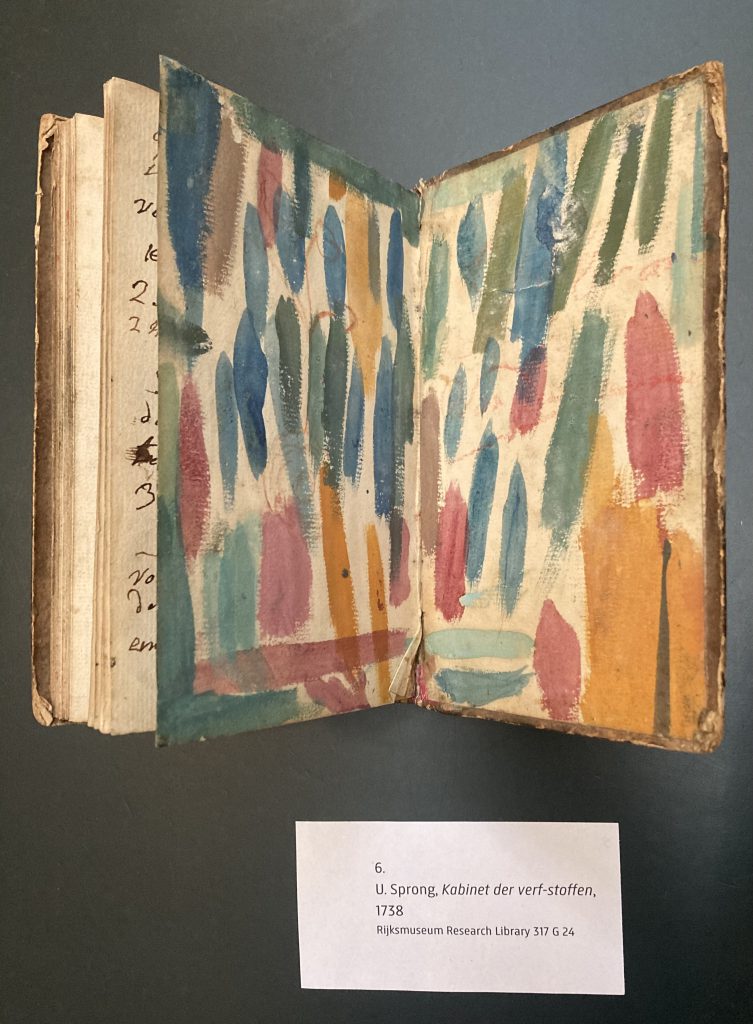

— Emile Schriver and Heide Warncke. 18 highlights from Ets Haim, the oldest Jewish library in the world. Walburg Pers, [2016].

Illustrated selection of books and manuscripts from the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam (founded 1616).

— — —

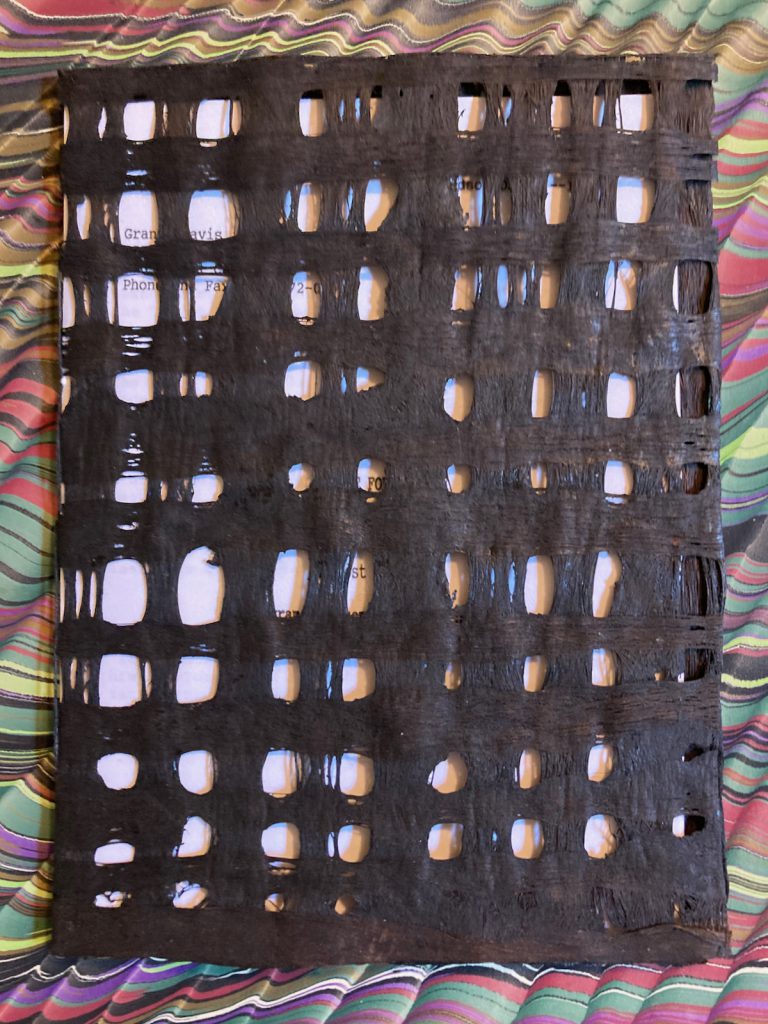

— Avram Davidson and Grania Davis. A Goat for Azazel. [Afterword by Michael Swanwick]. Dragonstairs Press, forthcoming 5 September 2024. Edition of 80 copies, stitched in mourning lacework paper wrappers, signed by Swanwick.

Reproduces the text of a proposal for an Eszterhazy “ghost novel” (circa 1993 or 1994), with a note by Michael Swanwick, whose friendship back then encouraged my researches and the formation of the Avram Davidson website.

— Nancy Isenberg. White Trash. The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America. [With a new preface to the paperback edition]. Penguin, [2017].

The persistence of early modern English hierarchies and economic structures from the earliest beginnings of the enterprise. Dispossession, servitude, and the upward concentration of wealth.

— — —

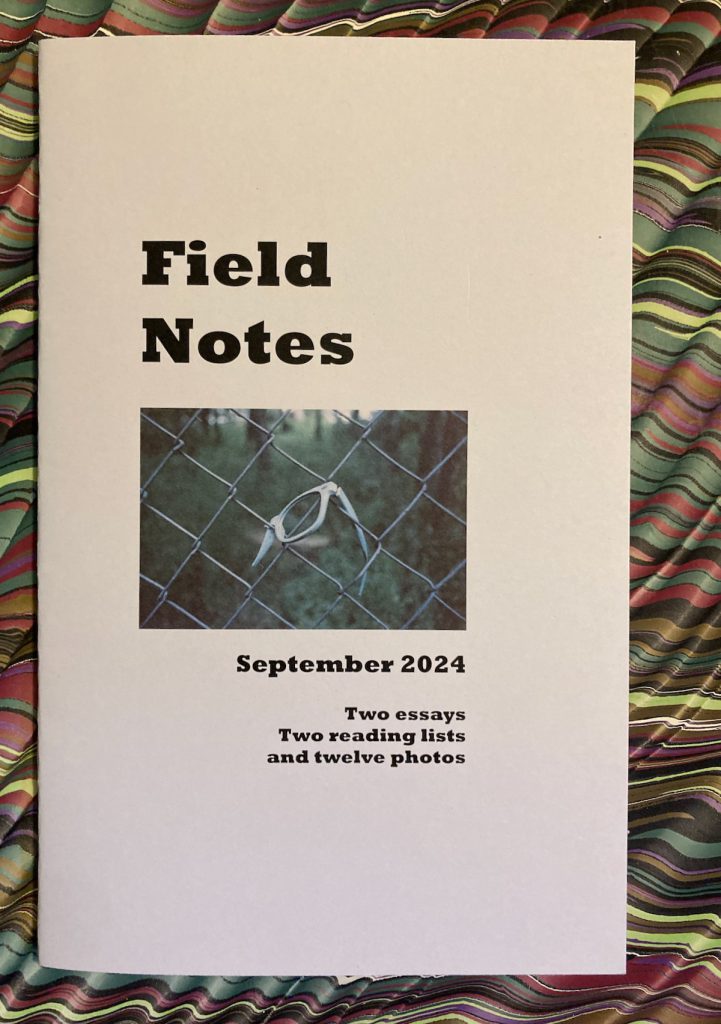

It feels like the end of summer here in Montclair, with the hop cones turning, and the tables at the farmers’ market asprawl with the last of the bulbous heirloom tomatoes and an abundance of pawpaws. And some interesting books in the the mail recently :

It feels like the end of summer here in Montclair, with the hop cones turning, and the tables at the farmers’ market asprawl with the last of the bulbous heirloom tomatoes and an abundance of pawpaws. And some interesting books in the the mail recently :