simply messing about in books

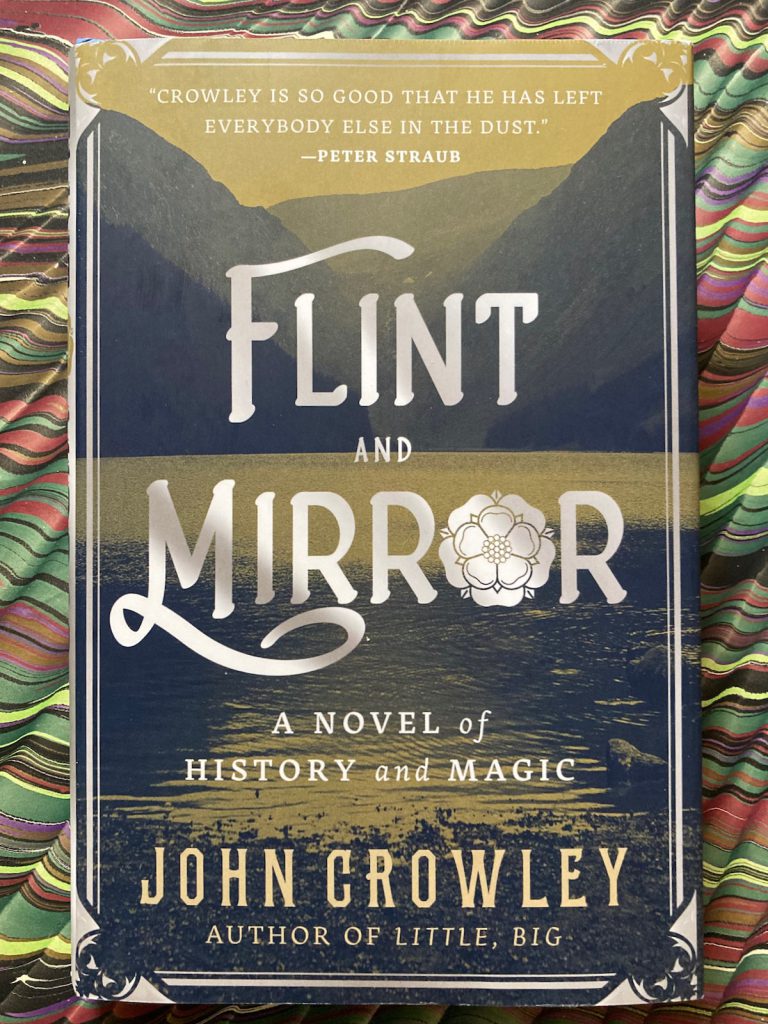

— John Crowley. Flint and Mirror. Tor, [2022].

Stories are told again and again. It is the telling that haunts us, and which we remember in our ears and hearts. Flint and Mirror is unlike any of John Crowley’s earlier novels, for it is a closely constrained historical novel of the life and times of Hugh O’Neill (1550-1616), who almost succeeded in overthrowing English rule in Ireland in the 1590s. If the legend of King Arthur is the Matter of Britain, the Tudor invasion of Ireland is the monstrous and chiefly unacknowledged truth that fixed the pattern of English adventurism around the world for centuries to come. The invasions continued under Queen Elizabeth I, and in Ireland as elsewhere, English policies fostered disunity among those who might have resisted the expansion of settlements. As one of the heirs to Gaelic lord of Tyrone, the young Hugh, Baron Dungannon, was fostered with the family of Sir Henry Sidney, Elizabeth’s deputy in Ireland (and father of the poet). Hugh was presented to the English court, and Elizabeth later referred to him as “a creature of our own”. Hugh O’Neill returned to Ireland and was appointed to various lieutenancies in Ulster. While his “position then resembled that of the many English captains serving in Ireland, he was more adept in advancing his interests because his Ulster origins allowed him to operate within two competing worlds” (ODNB). The English thought perhaps they had shaped a useful pawn, but having been “raised from nothing by her Majesty”, O’Neill soon put his own ideas into action.

The “two competing worlds” at the heart of Crowley’s novel are not, however, those of the historian, or not quite. To the four ancient kingdoms of Ireland is always added the fifth, the domain of those who live under the earth and in the lakes and rivers. The evening before Hugh is sent to England, the blind poet of his uncle’s castle takes him out to a tumulus at twilight, and the boy is presented to “a certain prince” who gives him tokens of a promise and a commandment. And later, one of his tutors is the wizard Doctor Dee, who also gives the boy a small secret object binding him to Queen Elizabeth.

This is not Pavane, Keith Roberts’ beautiful book which rewrites technology to articulate a backward-looking alternate history, for Flint and Mirror is an account of how the English victory rewrote the nature of Ireland. Three centuries would pass before Patrick Pearse proclaimed the Irish Republic and invoked “the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood”.

And yet. The entire novel is closely entangled with all the notions Crowley has always written about: liminal places, objects of power, consequences, Shakespeare, Doctor Dee, the fearsomeness of the Shee, imaginary books, and the changes of the world.

Hugh O’Neill’s childhood visit to the Earl of Desmond in squalid exile in London moves to a rich, astonishing image as the chapter concludes. And John Dee’s vision of the powers leaving Ireland in “no ships men sail, ships made out of the time of another age, silvered like driftwood, with sails as of cobweb” recalls the insubstantial armies and inconclusive battles of the war in Little, Big. Flint and Mirror is a beautiful book, sometimes elegiac in tone, and full of surprises.

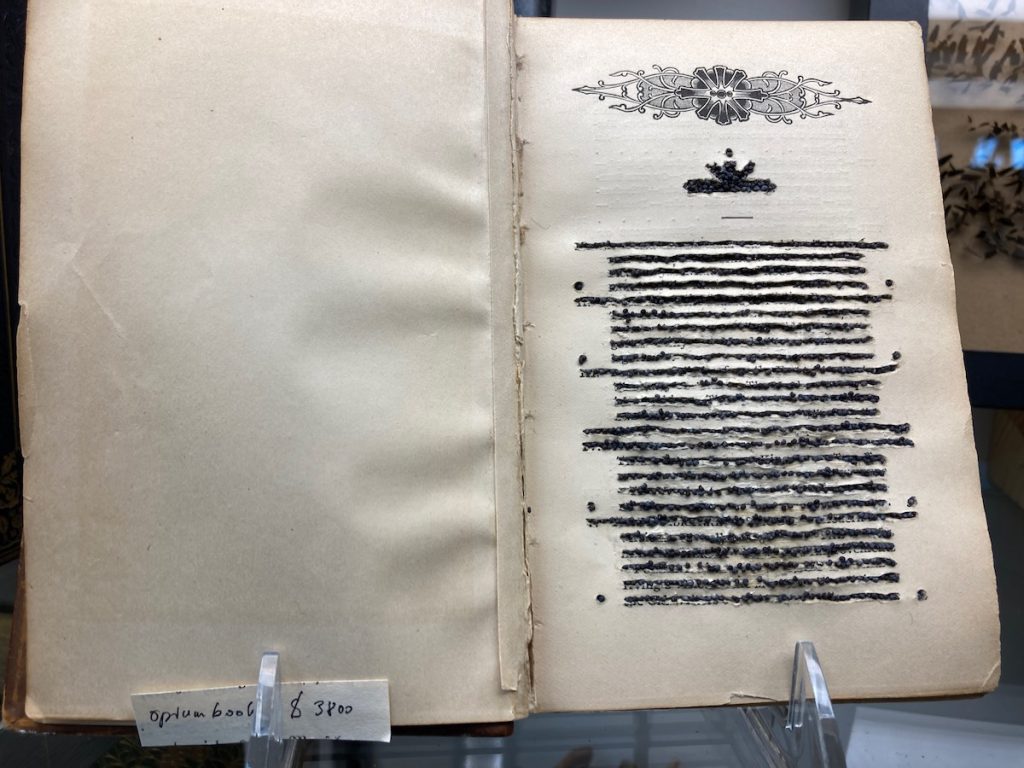

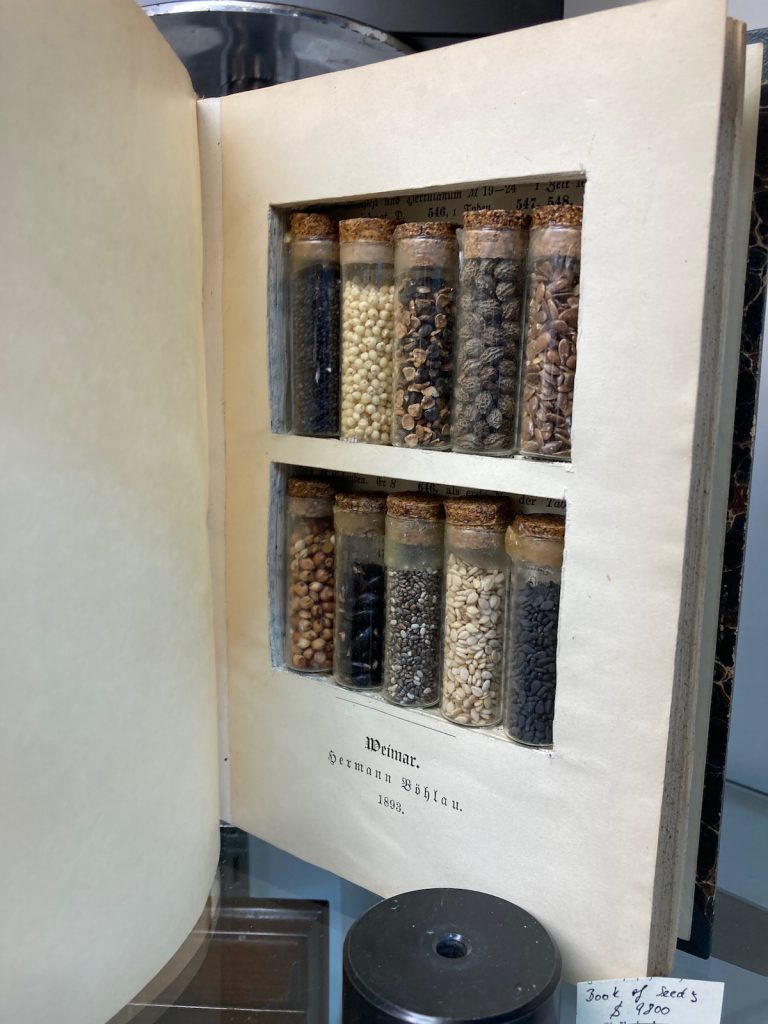

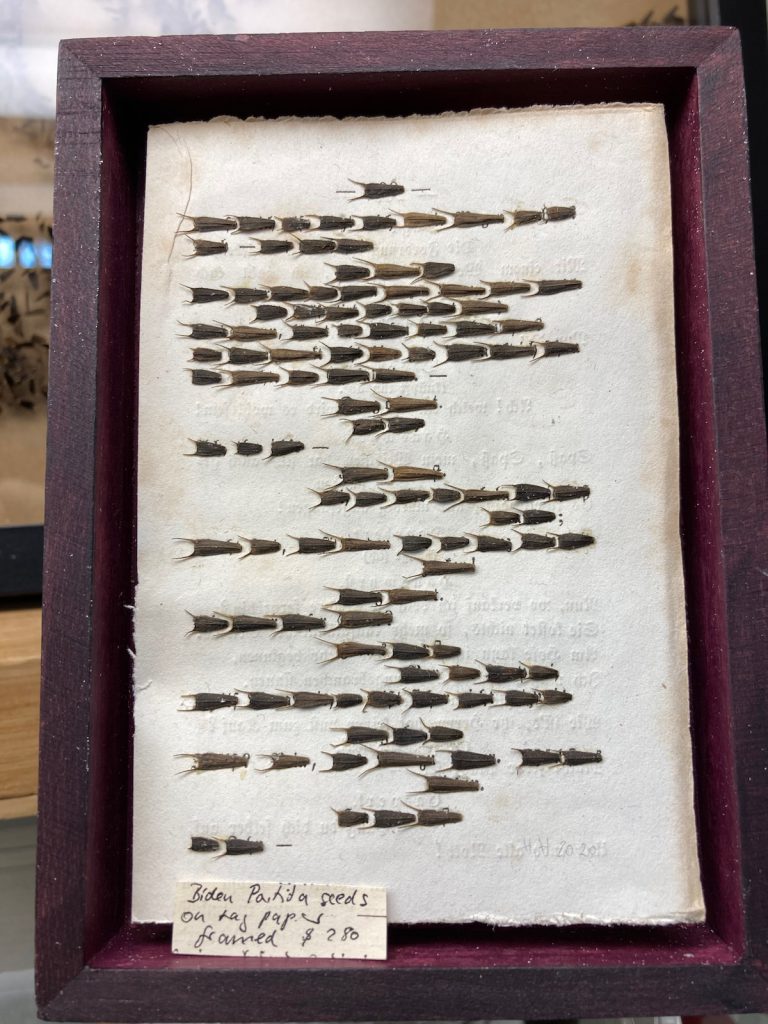

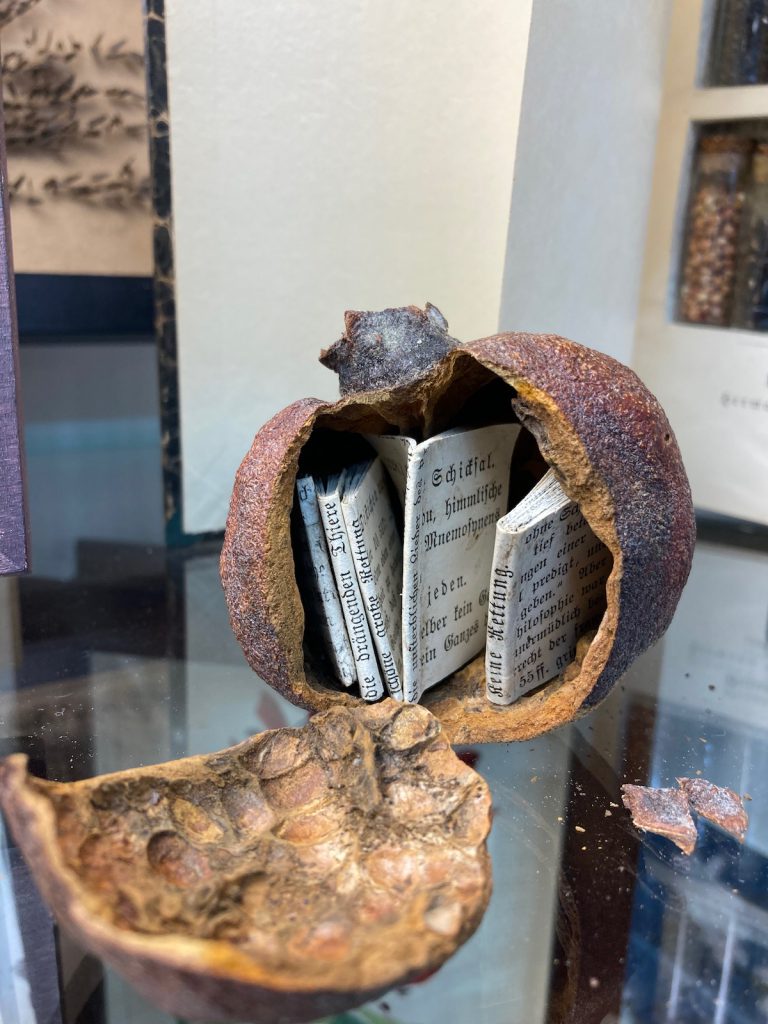

The most striking vitrine I saw at the recent New York Antiquarian Book Fair was this display of the artist books of Heide Hatry and related botanicals at the booth of Sanctuary Books. Hatry’s transformations are playful and provocative, and gorgeous to hold in the hand.

[Opium Book, with poppy seed text.]

[Book of Seeds]

[A prickly text.]

[Secret library in a pomegranate.]

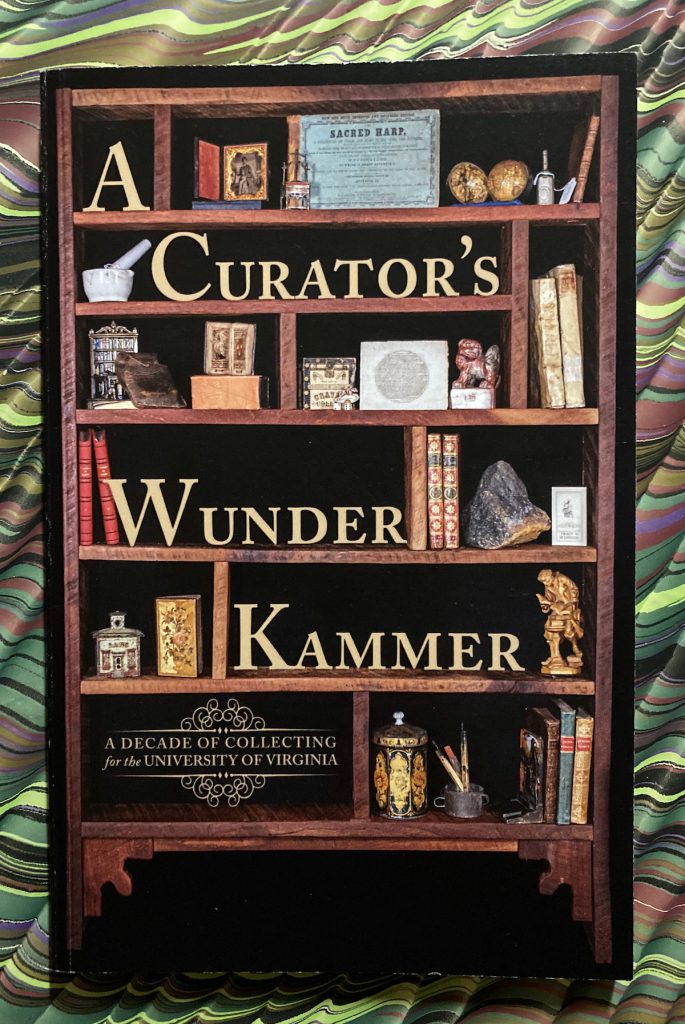

— David R. Whitesell. A Curator’s Wunderkammer. A Decade of Collecting for the University of Virginia. Exhibition Catalog. [Charlottesville: University of Virginia Library], 2022. Illustrated throughout. [iv], 105 pp. Edition of 500 copies [in fact, 310]. $25.00.

— David R. Whitesell. A Curator’s Wunderkammer. A Decade of Collecting for the University of Virginia. Exhibition Catalog. [Charlottesville: University of Virginia Library], 2022. Illustrated throughout. [iv], 105 pp. Edition of 500 copies [in fact, 310]. $25.00.

[Note: Some copies were issued with an added presentation leaf (inscribed to the individual booksellers identified as sources). The colophon states 500 copies printed, but due to paper shortages only 310 were in fact printed. If you want one, best to act soon. Details: https://at.virginia.edu/wunderkammer]

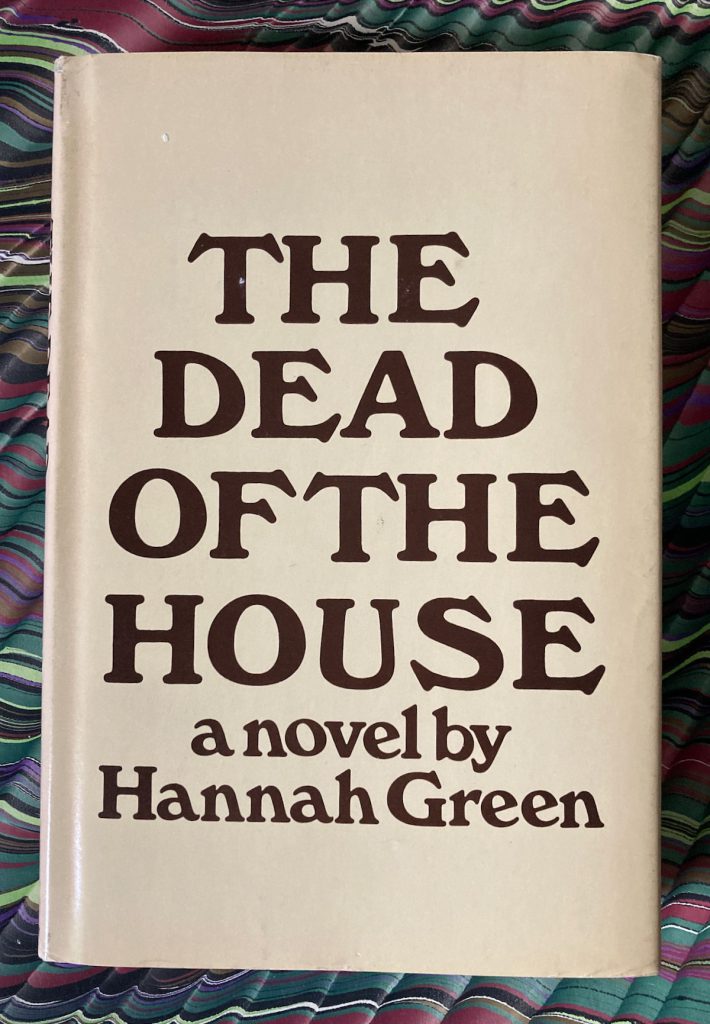

The Endless Bookshelf is many things, but it is above all a series of notes on reading and thinking about books, as texts and as objects. More than a decade ago, a friend gave me a copy of the paperback reprint of The Dead of the House by Hannah Green, deeming rightly that I would appreciate. I read it with pleasure and gave a copy to friend with an affinity for books and for the wood, and he enjoyed it, too. It was Green’s only novel (technically, in science fiction terms, a fixup composed of several linked stories), all the more remarkable for that, perhaps.

I often thought about the book over the years, and then not long ago I saw an inscribed copy of the original edition, published by Doubleday in 1972, and, as one does, thought about it some more. I began re-reading the book, and then turned up a more interesting copy.

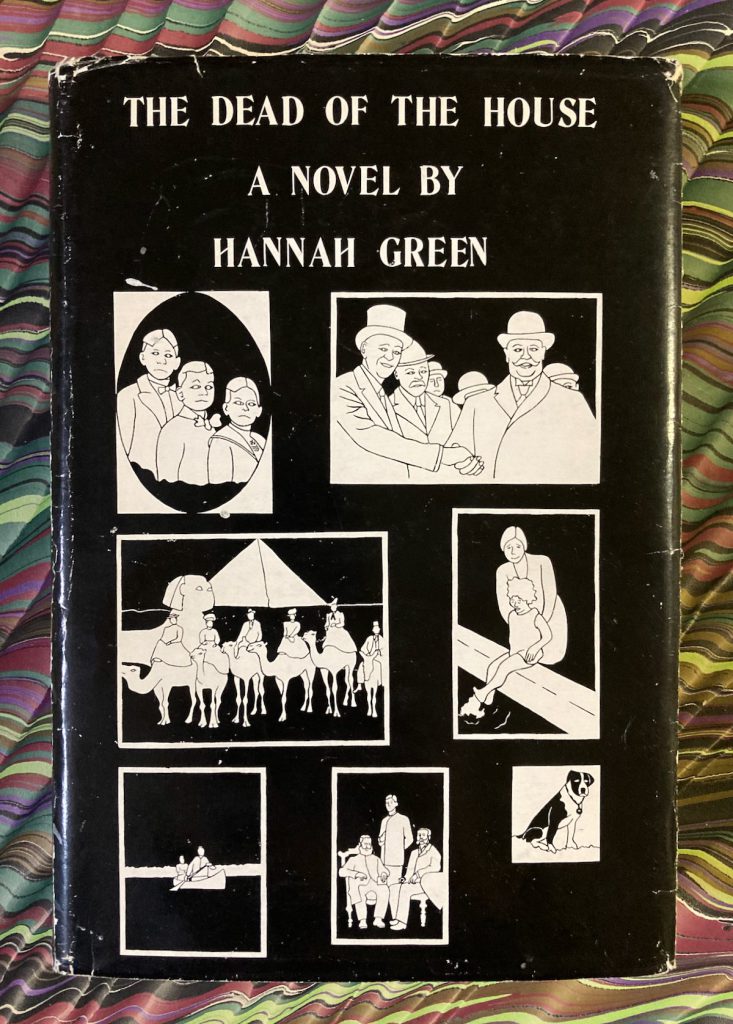

— Hannah Green. The Dead of the House. Doubleday, 1972. Inscribed by the author, “For Dieter With my Love Hannah New York, April 1972”. With printed pictorial dust jacket by John Wesley, inscribed on the blank front flap, “Cover for Dieter John Wesley 1972”, and retaining original publisher’s dust jacket with text front panel and author portrait on back panel.

Hannah Green (1927-1996) married painter John Wesley in 1971. His jacket images are closely linked to the text and the look is not dissimilar to his other graphic work at the time (especially some early works, such as Alice or the Radcliffe Tennis team) and a little more somber than the pop art motifs for which he is best known. Was it a trial proof for a design rejected by Doubleday ? And, of course, one wonders about the identity of the Dieter to whom the book is inscribed.* To be continued, perhaps.

[* possibly German artist Dieter Roth, whose work was sometimes exhibited with John Wesley’s at about this time.]

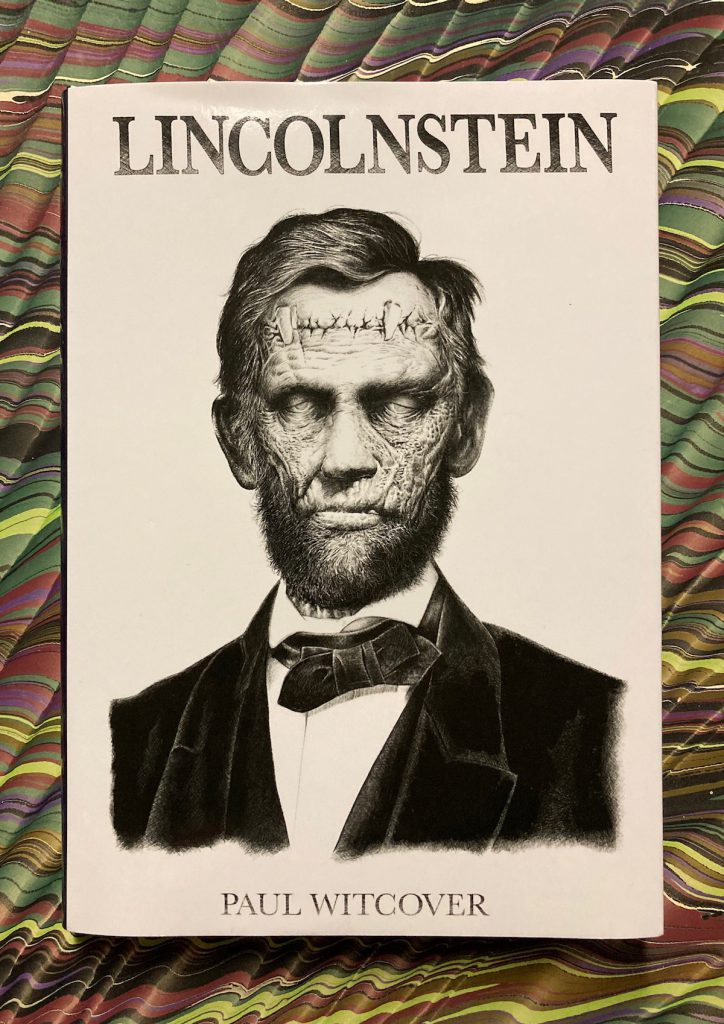

— Paul Witcover. Lincolnstein. A Novel. [Hornsea:] PS, [2021]. 155 pp. Pictorial boards, dust jacket after Carl Pugh.

Paul Witcover’s Lincolnstein is a concise and nimble critical fiction, an original and moving work expressed from the collision of historical incident and literary texts. It is a novel of ideas in motion, from the headlong rush of the kidnapping of a Confederate military surgeon by two spies from Pinkerton’s Union Intelligence Service to the shocking purpose behind their deed. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus is invoked upon the title page, but within the story the allusions emerge organically. President Lincoln has been assassinated and Stanton intends to put to use the theories of the brother of the doctor, one Victor —. “What brother? I have no brother.” is the response of the Confederate doctor who squeaks like a “Dutchman”, and yet he recognizes the apparatus assembled in the train-car laboratory. After warning, “Your President is dead […] If you loved him you would leave him that way”, the surgeon agrees, under duress, to perform the task. This conceit is bold enough, and then with the turn of a page the reader makes one more heart-wrenching discovery, and learns the other literary text with which the novel converses. Go read the book and experience it.

— — —

The resonances of Frankenstein are a stratum of bedrock, the earlier novel visible in the revulsion at the success of the process, in the flight of the monster, in the prodigious strength of the revived Lincoln and the polished oratory (Lincoln’s speeches rather than Milton’s Paradise Lost), and Mary Shelley’s novel propels the arc of the novel towards its conclusion. And yet, equally organically, the biggest and boldest of Witcover’s moves is to have Captain Finn lift the sheet from the face of another corpse in the laboratory, and in that act reveal who he is, and what his loss is. Finn’s initial disbelief yields to cold rage and he announces, “There has been a slight change of plans, Doc.”

That had been a life fit for kings. Catfish for supper, pipe always full, easy conversation all day as the shore slipped by in endless green unfurling, the river adding its voice to their own. He would have stayed there forever if he could.

A novel, like life, is motion and change, not stasis. The electricity stored in the laboratory revives the body of the president, and everything changes. Instead of the brain of the dead white bumpkin intended to render the president compliant, Lincoln’s skull now contains the brain of Jim Watson, who had been fatally wounded while helping Capt. Huckleberry Finn kidnap the doctor. Lincoln bursts from the train, and Finn pursues him, with orders from Pinkerton but with his own sense of mission. If Frankenstein impels the novel into action, the energy of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn shapes the subsequent course of events as Jim travels stealthily through the ruined landscape of war in search of his enslaved wife and children. Witcover writes short monologues, crisp vignettes of people who encounter the errant Lincoln and aid him on his way. These many supporting voices are one of the pleasures of the book.

— — —

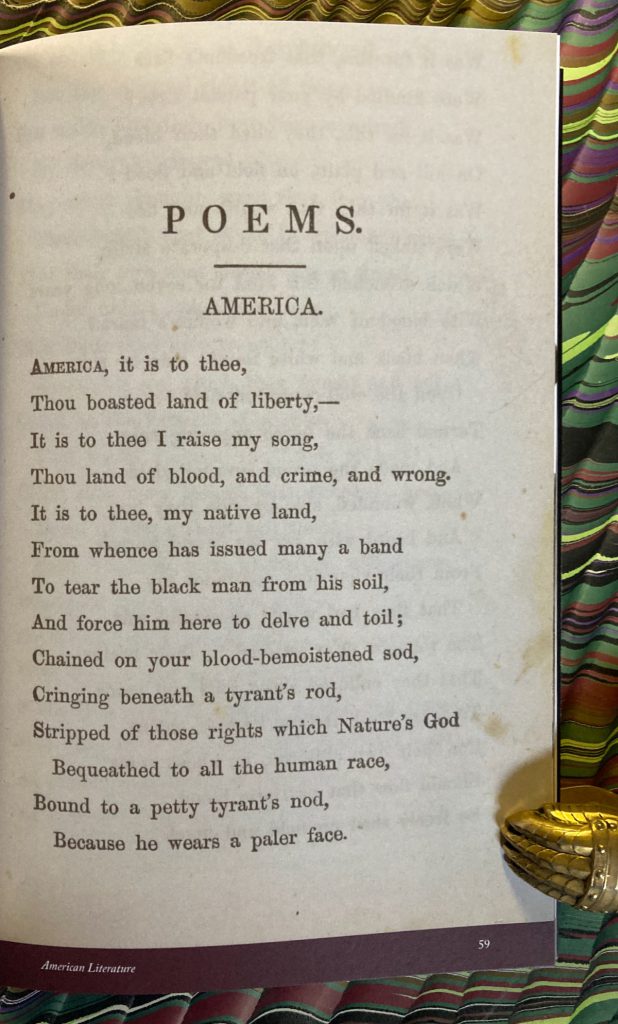

Did you really think the Matter of America leads to a happy ending? If the legend of King Arthur is the Matter of Britain, fraud and race are the Matter of America. The other day, I came across a pamphlet on racial equality and equal suffrage from 1865, in which the pretense of America as a “white man’s country” is dismissed by the black writers of the pamphlet: “Every school-boy knows that within twelve years of the foundation of the first settlement at Jamestown, our fathers as well as yours were toiling in the plantations on James River.”

Since Pinkerton has told Finn of the Mississippi plantation where Jim’s kin are being held, Finn dogs the reanimated Lincoln’s footsteps and they soon find each other. It is not an easy reunion, and Witcover deftly brings home blunt truths, in ways Clemens could only hint at in Huckleberry Finn and in The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and the Comedy Those Extraordinary Twins (1894). Jim as Lincoln is articulate about the relations between black and white in America:

There ain’t nothing you white folks like to believe in more than the idea of your own goodness. You will ignore all evidence to the contrary, just to make yourselves feel better about all the evil that you have done or allowed to be done in your name. Sure, white folks pity a blind man. But that ain’t nothing compared to the pity you feel for the real victims of this misbegotten world: your own damn selves. It’s a story you don’t never get tired of telling, nor of hearing.

This is very direct, perhaps I have not chosen the best passage, for the discussions of Huck’s black rage and Jim’s quest are natural and seamless and the infodump is nowhere to be seen.

Jim says of his Lincoln memories, “I can feel the tug of all that was dear to him. And hateful too. Everything that touched him, for good or ill. It’s like I’m a big old spider sitting at the center of a web he spun in life.” Huck remarks on the revived president’s “steady pumping heart”, but the voice and heart of the novel are Jim Watson coming to terms with the world and the body he now inhabits.

Witcover has found the appropriate mode to convey a common usage in the world of the novel, in simply writing n——, as profanity was once elided in Victorian fiction: every one knows the word, but we don’t, can’t use it the way it was used in 1865 (or in St. Petersburg, Missouri, in 1845, or in the novel published in 1885). That is the only concession made to current discourse, and there is no evasion of the brutality of the slave system or its intertwining with American life in North or South.

In Huck and Jim’s march to the banks of the Mississippi, Witcover’s novel converses or collides with aspects of Thomas M. Disch’s Camp Concentration (the brain swap), the recent novel by George Saunders, William Faulkner, Walt Whitman, and Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”. These are not merely allusions but are integrations and transformations of that material which advance the plot and present a critical response to the precursor texts. And the key text remains Huckleberry Finn. Disguised as a blind veteran and his loyal bondsman, Huck and Jim reach Terra, the vast, prosperous De Spain plantation, which remains untouched by war and emancipation. The gross, bloated Major de Spain has made sure of his accommodations with those in power. All these elements of deceit and cozying up to power and selfishness are discernable in Clemens’ novel. The deceptions are monstrous, far more appalling than the idea of reviving the corpse of Abraham Lincoln, and the rotten structure cannot withstand the monster’s rage. And then, in a beautiful concluding passage which links both Frankenstein and Huckleberry Finn, Jim leaves the burning plantation, carrying the corpse of the person inseparable from him — just as the monster carried Victor’s corpse out into the endless Arctic wastes, so Jim lowers Huck’s lifeless body onto a timber flatboat and joins the flowing river: “The raft receded, his upright figure silhouetted in the gleam of reflected flames. Then the current took him, and he was lost in darkness.”

[HWW]

24 January 2022

Your correspondent celebrates fifteen years of simply messing about in books on this website (it started here, but of course the mischief and fun and seriousness go back much further). There are a few regular readers of the ’shelf, and perhaps once in a while a new reader will come across something in the archives which cannot be found elsewhere. I continue to read Proust in the Pléiades edition, with great interest and pleasure; I am now at the stage of Le Côté de Guermantes, and there is no stopping. There are also other books which come to hand, as I usually have a second or a third book which I am reading, or at least reading at. Some of them are noted below. I omit the names of several bibliographies I have been consulting as these fall under work in progress.

I have written a few essays recently where the lead time for publication is rather longer than for the Endless Bookshelf: I received Paul Witcover’s new book late last week, read it, and finished the review a couple of days later; and even had time to look at it in the cold light of day before posting it. That flexibility is one reasion why I figure I will keep writing these chronicles of small beer for a while longer. Perhaps you will want to read them.

I am very much looking forward to reading Robert Aickman An Attempted Biography by R. B. Russell (Tartarus Press); I have read some of Aickman’s stories but by no means all of them.

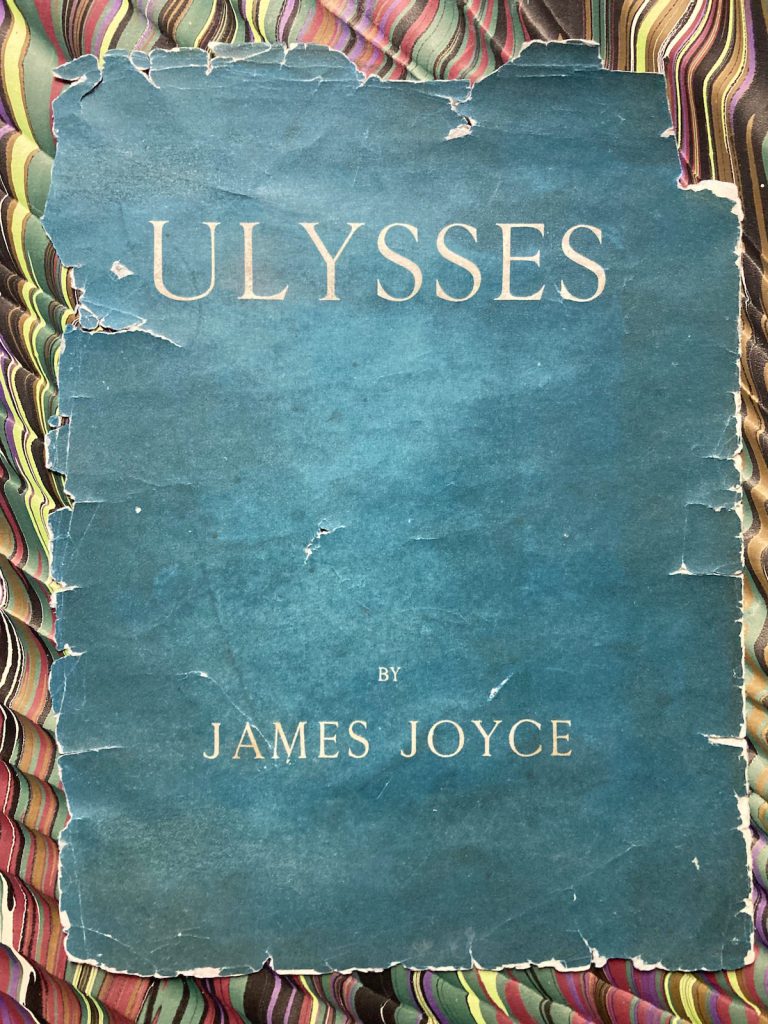

Wednesday 2 February marks the centenary of James Joyce’s Ulysses, published as a book in Paris on the author’s fortieth birthday in 1922. This is the darkened and tattered remains of the front wrapper of one of the 750 ordinary copies of the first edition, one of those scraps of paper which demand to be saved.

— — —

In February, I expect to be at the California International Antiquarian Book Fair in Oakland, booth 504 (James Cummins Bookseller) at the Oakland Marriott City Center, Friday 11 February through Sunday 13 February. If you are in the Bay Area, come by and say hello (and please let me know in advance if you would like a pass).

— — —

recent reading

— Henry C. Mercer. November Night Tales [1928]. [Introduction by Peter Bell]. Swan River Press, 2015.

Supernatural tales by the Pennsylvania polymath archaeologist, ceramicist, and polymath Henry C. Mercer (1856-1930), who was educated at Harvard (Class of 1879) and as a ceramicist played a key part in the American Arts and Crafts movement. His poured concrete mansion, Fonthill — named for William Beckford’s Gothic folly — is a turn of the century wonder; and his collections of American tools and vernacular objects pioneered the preservation of what is now called material culture. These stories range from rural Pennsylvania folklore to a forgotten treasure in the Italian Alps. The best of them is “The Wolf Book”, a tale of werewolves in the Balkans and an ill-starred book.

— Richard Thompson, with Scott Timberg. Beeswing. Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2021.

Memoir by one of the founders of Fairport Convention; his fabulous 1968 dream of Keith Richards and south London is worth the price of admission. Thompson played a solo acoustic show at a local Montclair venue not too long before the pandemic, and “1952 Vincent Black Lightning” was one of the great moments of that evening. Thompson’s songs express — like the late novels of Russell Hoban — the curious notion that loss is the great creative well for literature and song. Sad and beautiful can be triumphant at the same time, because the song outlasts the sorrow.

— T. Frank Muir. Hand for a Hand. Soho Crime, [2012]. Crime novel set in St. Andrews, Scotland.

— Sara Gran. The Book of the Most Precious Substance. A Novel. Dreamland Books, [2022].

— Michael Shea. Mr. Cannyharme. A Novel of Lovecraftian Terror. Foreword by Linda Shea. Edited by St. Joshi. Hippocampus, [2021].

San Francisco at the beginning of the AIDS crisis, with interdimensional beings, written by Michael Shea circa 1981. I found the first half of the book interesting, with well grounded scenes around the Tenderloin hotel managed by the writer-protagonist, and some choice, weird secondary characters. My interest waned as the supernatural elements unfolded.

‘merging, not with the car, but with the road’

— Brendan C. Byrne. Accelerate. 96 pp. Small 8vo, [Moonachie, New Jersey], 2022 [i.e., 3 November 2021]. Pictorial wrappers, dust jacket with french flaps. From a small edition printed for the author just before the publication of the e-booke by Neotext. The title page verso reads Copyright 2020.

This is a remarkable book. In a future Los Angeles, couriers caged with their autonomous vehicles pound nutritional “sluice” and make deliveries at 198 m.p.h. Joam has refused to let the hardware make all his driving decisions yet lives almost integrated within his armored “beater”. He receives a commission to deliver a packet to New York within 72 hours. The narrative is all attitude and the lingo is a brilliant street jargon, an immersive account of Joam hurtling across the landscape of American political collapse, seeing off jealous rivals. Some of Byrne’s earlier work, such as “a Stone and a Cloud”, seems to chart the erosion of humanity in the technological future. Accelerate is a gonzo cross-country road-trip — west to east — which tells a moving story of personal loss as, paradoxically, the machine becomes human. The best book of the year 2021.