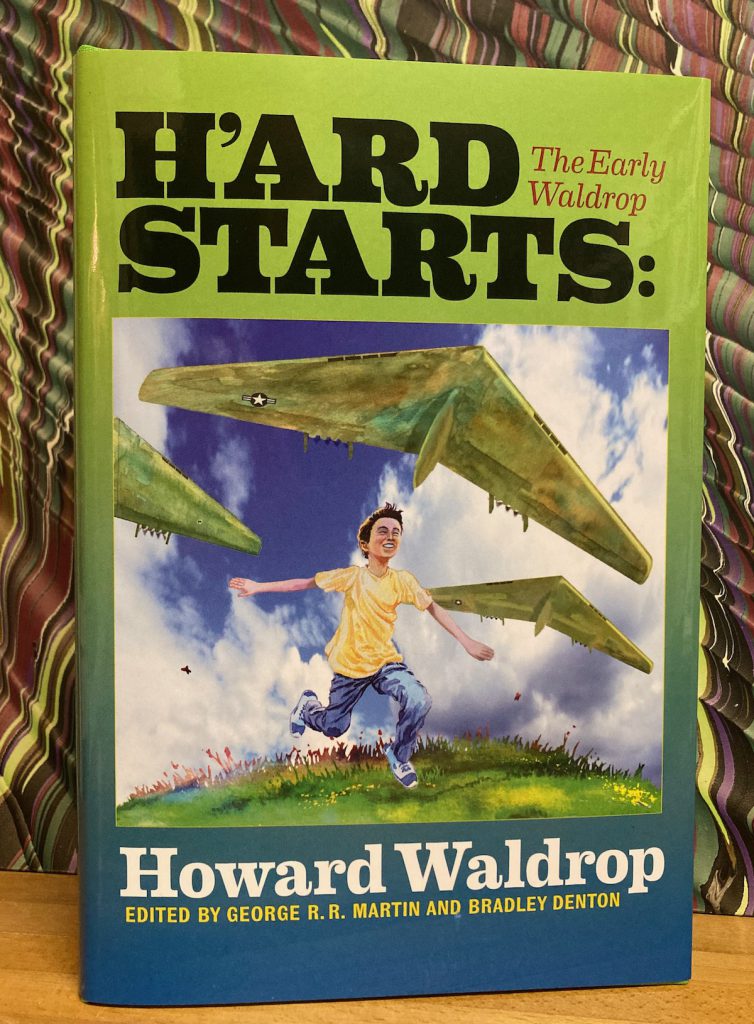

In Memoriam : Howard Waldrop

Howard Waldrop (1946-2024) was an American national treasure, author of many memorable stories and novellas, among them “Winter Quarters”, “Heart of Whitenesse”, and The Ugly Chickens. If you don’t know his work, you have some strange delights ahead. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction is always a good place to start:

https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/waldrop_howard

Lawrence Person wrote a brief and oddly touching memorial note, here.

— — —

— Dylan Thomas, from “In my craft or sullen art”, in Twenty-Six Poems :

[. . .]

Not for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

— — —

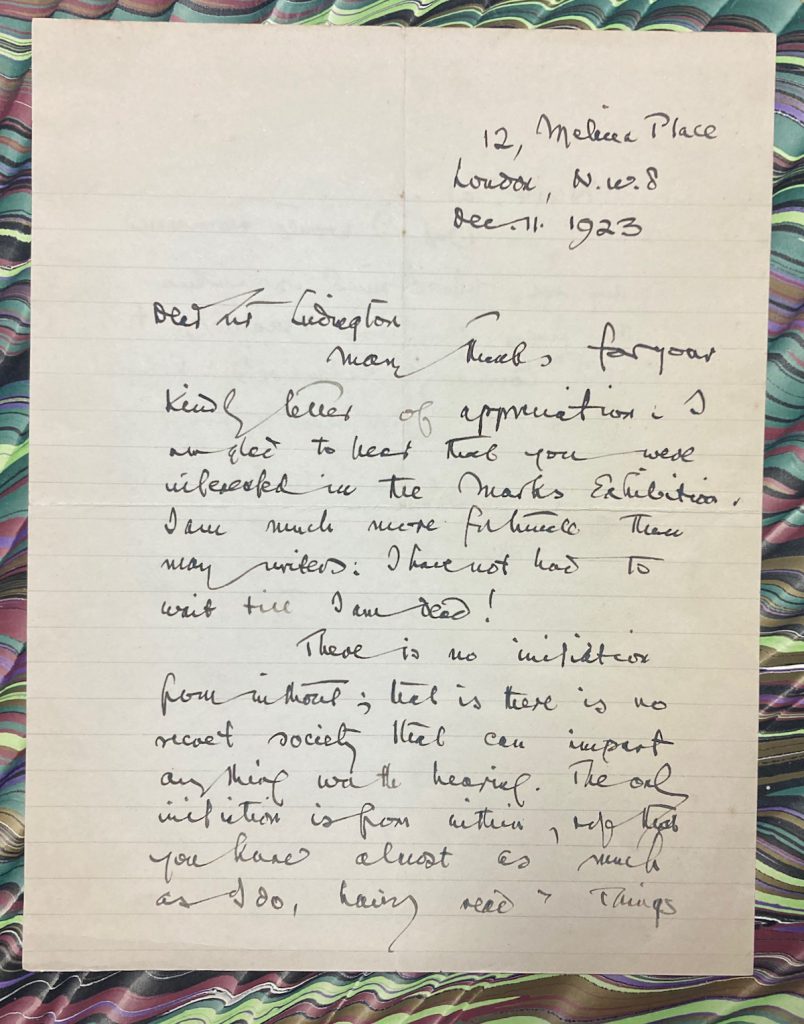

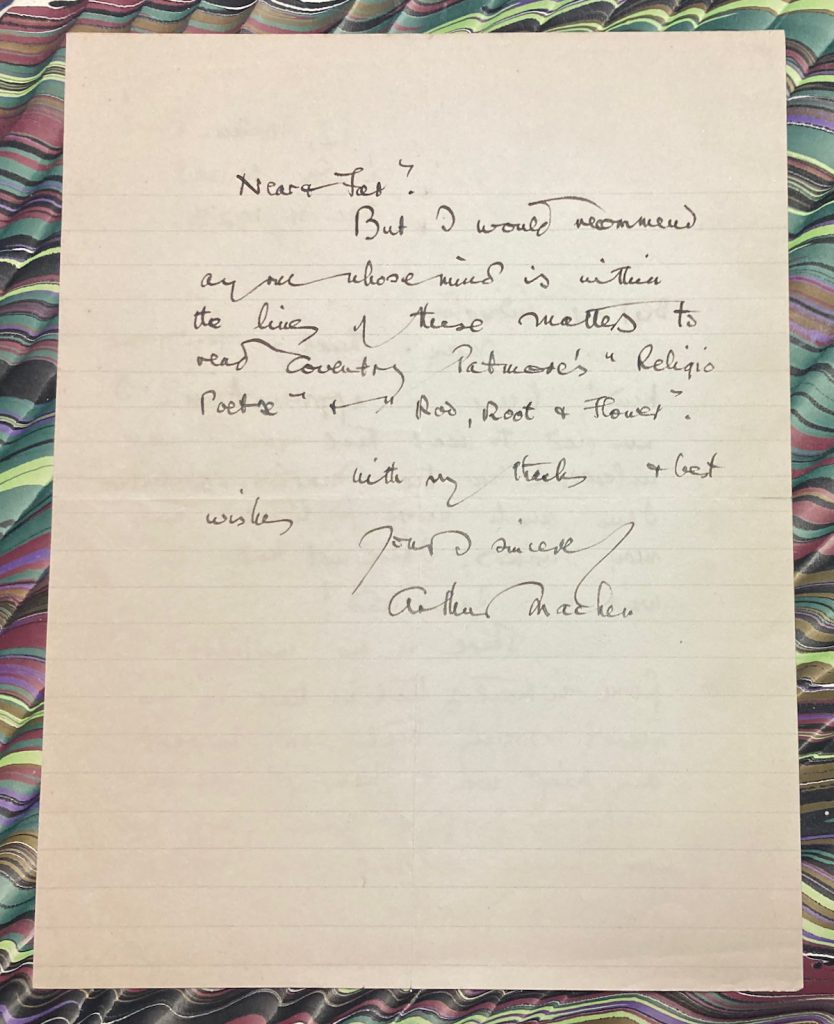

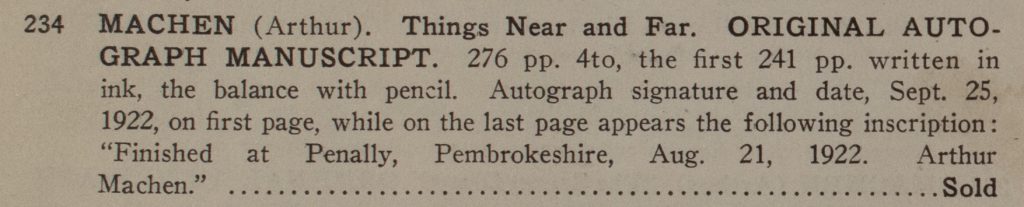

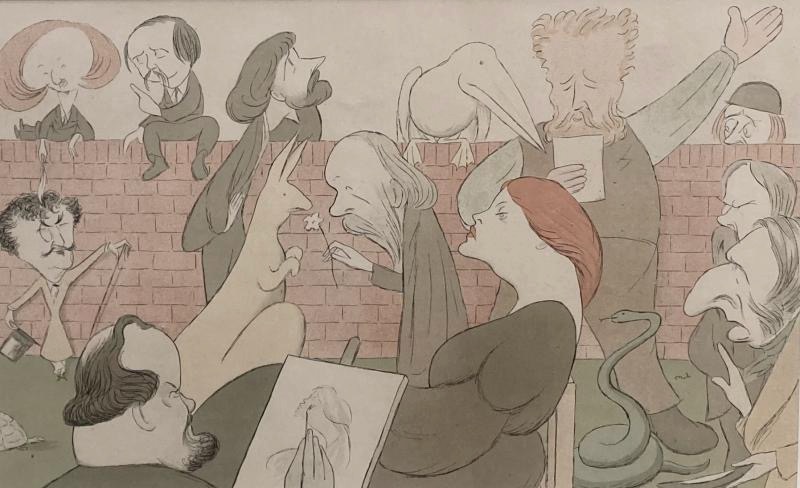

Sidney Sime Exhibition

A major exhibition of the work of Sidney Sime, (from the artist’s collection and archive at the Memorial Hall in Worplesdon, Surrey) is being held at the Chris Beetles Gallery in London, with an excellent digital simulacrum for those of us who won’t be in London before 27 January

(via Mark Valentine’s Wormwoodiana)

— — —

In Memoriam : Tom Purdom

Michael Swanwick wrote a heartfelt farewell to his friend “Tom Purdom, Heart of Philadelphia”, here.

— — —

from the latest number of the Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. LXXX, no. 1 (Autumn- Winter 2023) :

— Stephen Ferguson, “Rare Books at Princeton, 1873-1941”

It was not self-evident that the American colleges of the nineteenth century would become collectors of book rarities, any more than it was self-evident that they would become universities, build football stadiums, and create an education eagerly sought worldwide. But the various decisions that resulted in these choices have much to do with one another — even when each leads down a path that appears to diverge widely from the others.

— Alfred L. Bush, “How Empty Shelves in Firestone Ultimately Revealed America’s Earliest Book”

“But with the determination of the ignorant . . .”

— — —

In Memoriam : Terry Bisson

Even now, in remembering Terry Bisson (1942-2024), I can’t help but smile. It’s a sad smile today, but Terry was one whom I always remember with a smile on his face. I encountered his work with Talking Man, one of the great short American novels of a fantastical, mysterious South; and then I started reading some of his fine short stories. He and Alice Turner founded the KGB Fantastic Fiction reading series now conducted by Ellen Datlow and Matthew Kressel. Terry Bisson also founded the PM Press Outspoken Authors series of interviews. Trickster Michael Swanwick recalls “Three Things You Must Know about Terry Bisson”.

— — —

“The Black Lands”, published in Exacting Clam 10 (Autumn 2023), will be reprinted in the issue of the Book Collector for summer 2024.

— — —

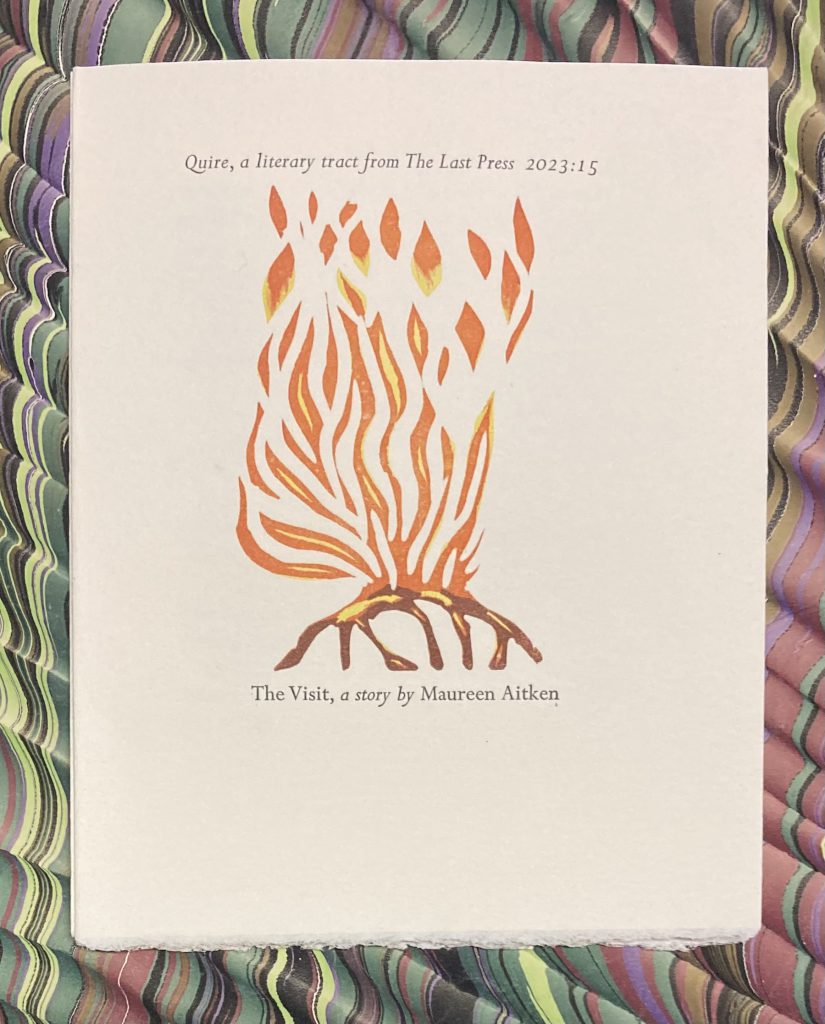

I came across a beautiful literary ’zine from the Last Press, Quire, issue 19 (2023) of which is a separate edition of a Mark Valentine story, “Qx”, as a finely printed trifold sheet. Quire 13(2022) is The Mark of Andreas Germer by Ron Weighell, a special Christmas ghost story edition about the perils of reading. It’s a twelve-page chapbook with an engraving by Ladislav Hanks. No. 15 (2023) is The Visit, a story by Maureen Aitken (below). Production values are very high, and print runs small, so have a look, here.

— — —

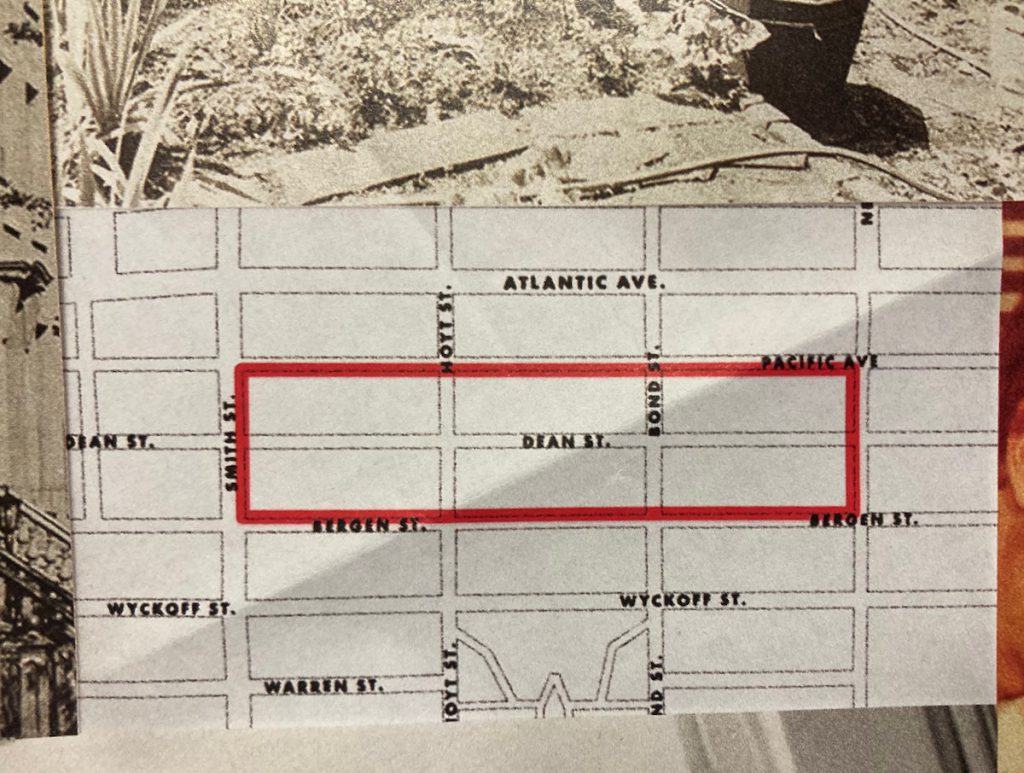

This time next week (Monday 22 February), your correspondent will be at the ABAA Bibliography Week Showcase, a small book fair held at the Alliance Française on east 60th street in New York City, details here :

https://www.abaa.org/events/details/bibliography-week-showcase

(free & open to the public, come say hello at the Cummins table)

And not long after that, in San Francisco at the California International Antiquarian Book Fair, 9-11 February. Come say hello (Cummins booth 105).